It’s the most common complication of childbirth. It went untreated for millennia.

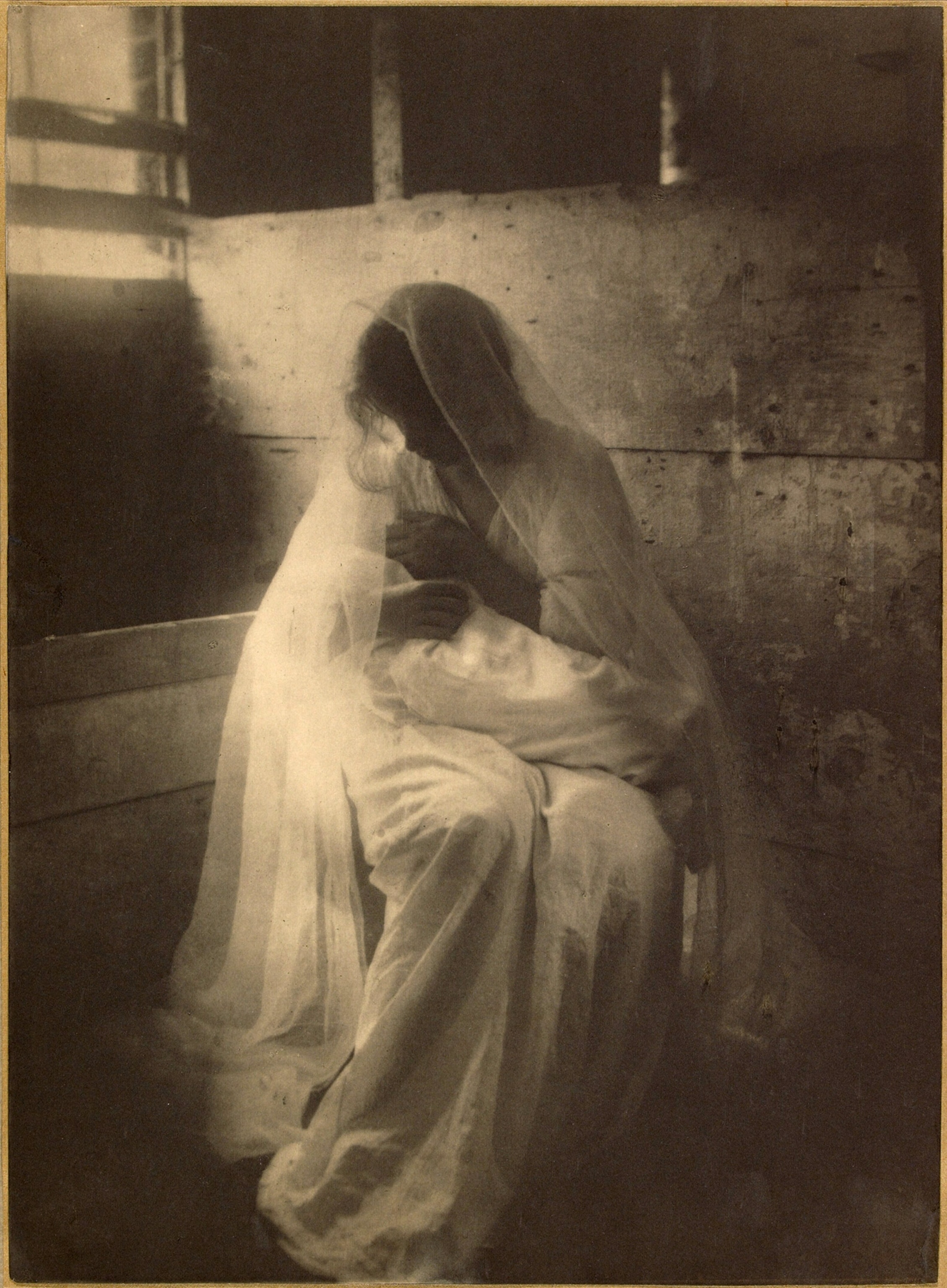

Physicians throughout history thought postpartum depression could be resolved by rebalancing a woman’s bile or through punitive “rest cures.”

Hysteria. Mania. The baby blues. Postpartum depression is an inescapable facet of modern parenting. Though estimates vary, one in seven females develops symptoms of depressive disorders after giving birth—and with the pandemic, prevalence of the most common childbirth complication has increased dramatically.

But the condition is older than you think—and it’s gaining more awareness, and treatment, than ever before. This summer, the federal Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral medication specifically designed to treat postpartum depression in adults.

(7 simple innovations that could save millions of mothers and babies.)

Why has it taken so long for postpartum depression to be recognized and relieved with its own medication? Here’s a brief history of postpartum depression, and why it may be partly driven by societal roles, not biology.

Postpartum depression in ancient times

Today, postpartum depression is considered to be a serious mental illness, affecting a parent’s ability to connect or care for their child and lasting for up to a year. But in the past, grieving or depressed mothers were often characterized as insane, unnatural, or damaged.

Ancient Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus, who wrote an influential first-century A.D. treatise on gynecology, wrote that women could experience irritation, become sad, and even harm their children after childbirth. “Angry women are like maniacs and sometimes when the newborn cries from fear they are unable to restrain it, they let it drop from their hands or overturn it dangerously,” he wrote.

Another ancient medical pioneer, Hippocrates, wrote of “bilious” women experiencing hallucinations and insomnia after giving birth, symptoms that align with the modern diagnosis of postpartum psychosis.

(Even today, women's health concerns are dismissed more and studied less.)

The idea that too much bile could play a role in women’s postpartum mental health was surprisingly long-lived. Humoral medicine—the theory that imbalances of blood, phlegm, and yellow and black bile were responsible for all physical and mental ills—thrived for 2,000 years, even up to the Industrial Revolution. It also gave rise to the word melancholia—from Greek for “black bile,” and the concept of black bile contributing to depression thrived for 2,000 years.

Demonic depression

Obstetric medicine and women’s health care was often provided by women in a time before the professionalization of the field. Long considered women’s work, childbirth was outsourced to midwives and family members. Though midwives and women in the community supported one another through postpartum depression with folk medicine, childcare, and as a sounding board, accounts of postpartum grief were rarely written down by mothers themselves.

One exception was Margery Kempe, a British mystic and the author of the first English autobiography. Dictated in the early 15th century, the text recounts how Kempe experienced visual and auditory hallucinations after giving birth, leading to self-harm and thoughts of suicide. Kempe attributed her experience to the devil’s influence.

“Like the spirits tempted her to say and do, so she said and did,” Kempe said. She only received relief from her suffering by negotiating with her husband to end their sexual relationship. Instead, she offered God her chastity—and sidestepped further mental health crises, write medievalists Diana Jeffries and Debbie Horsfall.

The 'rest cure'

By the mid-19th century, Western medicine was professionalizing, and male doctors supplanted the midwives who had once provided mental health care after birth. At the same time, the field of psychology was also making strides and there was a more concerted effort to treat women’s various psychological challenges—though they were usually grouped under the banner of “hysteria.”

(How PTSD went from "shell-shock" to a recognized condition.)

Among the most recommended, and controversial, treatments, was the “rest cure,” which involved up to months of absolute isolation for women with “female troubles” like postpartum depression. Popularized by 19th-century American neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell, the intentionally punitive cure required weeks of bed rest without being allowed to perform any activity, even reading or sewing. Patients were isolated from friends and family, and prescribed—and sometimes force-fed—a heavy diet.

“The rest I like for [female invalids] is not at all their notion of rest,” Mitchell wrote. “To lie abed half the day, and sew a little and read a little, and be interesting and excite sympathy, is all very well, but when [women] are bidden to stay in bed a month, and neither to read, write, nor sew, and to have one nurse, – who is not a relative – then rest becomes for some women a rather bitter medicine, and they are glad enough to accept the order to rise and go about.”

One patient—and critic—of Mitchell’s was Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who published a semi-autobiographical account of postpartum depression and the rest cure in her 1892 short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper.”

“Nobody would believe what an effort it is to do what little I am able,” the story’s narrator writes. “…such a dear baby! And yet I cannot be with him, it makes me so nervous.” Confined to a bedroom by her physician husband, the narrator eventually goes mad and imagines she is trapped inside the details of the room’s “repellant” yellow wallpaper.

Now considered a classic work of feminist literature, the story aroused strong opinions among readers. “It was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy,” Gilman later wrote, adding that her own rest cure had driven her “so near the border line of utter mental ruin that I could see over.”

Modern mothers and mental illness

Debates continued to rage in the 20th century about the nature of postpartum depression and how to treat it. One school of thought held that childbirth simply activated existing mental illnesses. Other scientists, like Russian American psychoanalyst Gregory Zilboorg, claimed personality flaws, frigidity, secret incestuous desires, latent homosexuality, or even jealousy of one’s own baby was to blame.

But still other researchers suspected the blame lay with some physiological process related to newly discovered chemicals in the body—hormones.

(Scientists are also starting to unravel what happens during menopause.)

Explanations of postpartum depression still vary to this day, but the dominant theory is that mental illness after childbirth is likely caused and contributed to by a variety of factors. These include, but are not limited to, hormonal changes after childbirth, sleep deprivation, post-traumatic stress, and the expectations modern society places on parents.

Nowadays, a brief period of “baby blues” is considered common, but longer-term perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are classed separately. Under current diagnostic standards, postpartum depression is usually classed as a major depressive disorder, and researchers estimate that half of all major depressive episodes actually begin prior to delivery.

But the modern era has also birthed new ways of looking at postpartum mental health. One is the theory that mental health issues after giving birth are a natural part of the transition to parenthood. In the 1970s, anthropologist Diana Raphael coined the term “matrescence” to define that transition. Matrescence is “the time of mother-becoming,” a biological, cultural, and community event in which a woman assumes her new role as parent, Raphael wrote.

In 2015, psychologists Aurélie Athan and Heather L. Reel called for a revival of the term. Athan argues that matrescence is a period of emotional and social growth similar to adolescence—and that it offers new mothers and medicine alike a way to explore and identify their experiences of motherhood, good and bad.

“Women who transition through preconception, pregnancy and birth, surrogacy or adoption, to the postnatal period and beyond, experience [an] acceleration in multiple domains true of any developmental push,” wrote Athan in 2019. She argues that the time is ripe to add the idea of matrescence to society’s understanding of postpartum depression—an understanding that has taken centuries to reach.