40-Year-Old Russian Engine at Heart of Rocket Investigation

Refurbished Soviet rocket engines involved in the accident will draw the attention of investigators.

The fiery destruction of an Antares rocket left behind a launch pad covered in debris and questions about the rocket's use of refurbished Soviet-era engines.

Investigators combed through the wreckage of the "catastrophic anomaly," as NASA termed it, one day after the crash at NASA's Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia's Eastern Shore. The rocket, valued at more than $200 million, was carrying a Cygnus cargo spacecraft containing food, equipment, and science experiments intended for the International Space Station. (See "Rocket Explodes, Aborting NASA Mission to Resupply Space Station.")

At a news conference on Tuesday evening, Bill Wrobel, director of the NASA facility, reported that safety officers blew up the rocket within 20 seconds of its engines firing up, when it became apparent that the launch was headed off-course.

"What we know is pretty much what everyone saw on the video," said Frank Culbertson of Orbital Sciences, based in Dulles, Virginia, which owned the rocket. "The ascent stopped; there was some, let's say, disassembly of the first stage, it looked like; and then it fell to Earth."

With help from NASA, Orbital Sciences and Federal Aviation Administration investigators will follow three lines of evidence—video of the launch, telemetry readings from the rocket, and the leftover debris—as they seek to explain the catastrophe.

The launch was the third of eight space station resupply missions by Orbital Sciences that NASA contracted for in 2008 at a total cost of $1.9 billion. NASA's William Gerstenmaier said that "contingencies" were written into the contract with the space launch firm to deal with just such a loss. Space station crew members have four to six months' worth of extra food at all times, in case a cargo ship misses a delivery, he said.

"At a minimum, Orbital Sciences is going to have to stand down on its launches until we learn the cause of this disaster," says veteran space industry observer Keith Cowing of NASA Watch. "The emphasis we are hearing from NASA here is all about safety."

Lunar Rockets

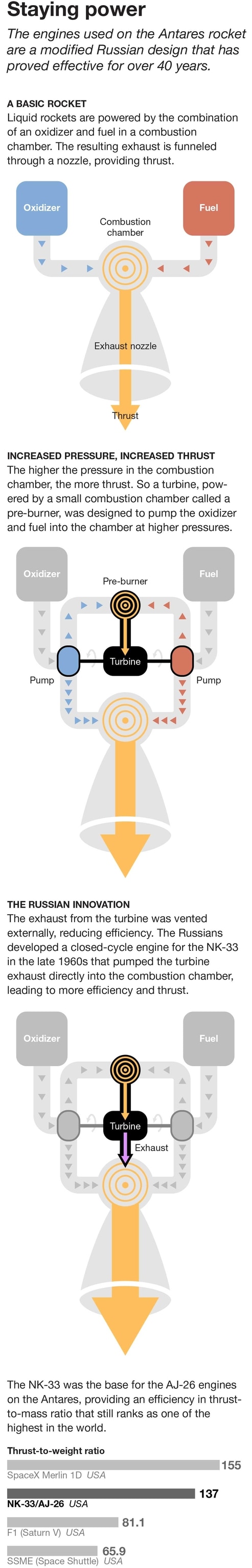

The first-to-fire "first stage" of the rocket used two NK-33 rocket engines originally built more than 40 years ago to power a planned attempt by the Soviet Union to land cosmonauts on the moon. That effort ended with four failures of the Soviets' gigantic N-1 rocket, one of them a colossal blast that ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions in history.

After the U.S. won the race to the moon in 1969, the Soviet program was dissolved in 1974. Its remaining rocket engines ended up warehoused or used in smaller Russian rockets.

"I think it's safe to say this will reopen the debate over the use of Russian hardware," says Cowing. "Russian rockets are famously rugged and reliable, but there will be questions about inherent flaws in using something this old."

About 40 of the rocket engines were purchased, reportedly for an astonishly cheap $1 million apiece, by Aerojet in the mid-1990s. Development costs for new rockets can run into the hundreds of millions of dollars, with uncertain outcomes. SpaceX's Elon Musk says the cost of developing the Falcon rocket was $300 million.

NASA's budget has steadily shrunk as a percentage of federal budget outlays since the early 1970s, leaving the agency little funding for developing its own cargo rocket after the retirement of the space shuttle.

Refurbished with modern electronics and steering mechanisms, the engines were rechristened as Aerojet AJ-26s. They passed testing at NASA's Stennis Space Center in Hancock County, Mississippi, and at Wallops. Then they were used successfully three times (once was a demonstration) to launch Cygnus supply spacecraft.

The ones aboard the Antares that blew up on Tuesday had also passed testing at Stennis and Wallops, Culbertson said.

Engines Questioned

Musk criticized the use of the Cold War rocket engines in 2012, telling Wired magazine, "their rocket design sounds like the punch line to a joke." The Hawthorne, California, company's Dragon missions competed with Cygnus for NASA's $3.5 billion space station resupply contract, which ends in 2016.

At a press conference after the mishap, Culbertson defended the engines' reliability, saying the firm went to great lengths to maintain and test them before firing.

In May, another NK-33/AJ-26 engine failed during a test firing at Stennis. The investigation into the cause of that failure is also still under way.

Russian Wrangling

This isn't the first time U.S. use of Russian space technology has raised hackles. U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz capsules to deliver astronauts to the space station in the wake of the space shuttle's retirement, even during conflict over Ukraine, has caused disputes in Congress.

Musk, meanwhile, has protested that another competitor, United Space Alliance, relies on Russian RD-180 rocket engines in its Atlas 5 rockets supplied to the U.S. Air Force.

After the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011, the move toward commercial suppliers of rockets to NASA was seen as a strategic move that freed the space agency to focus on exploration, rather than humdrum resupply missions. Awarding contracts to commercial suppliers, in turn, would help build a domestic space industry.

The disaster seems unlikely to derail the trend toward U.S. reliance on private launch firms. A 2012 Government Accountability Office report noted that such launches are expected to increase through this decade, driven by space station resupply missions and space tourism. NASA last month unevenly split a $6.8 billion contract between SpaceX and Boeing to deliver astronauts to the orbiting lab starting in 2017.

"The thing to keep in mind in all this is that we don't know what caused the mishap," Cowing cautions. "We all saw the explosion at the bottom of the rocket, but that doesn't mean anything. These investigations take time, and sometimes we don't even end up with all the answers."

Follow Dan Vergano on Twitter.