Why Didn't Toxic Waste Cause a Cancer Epidemic, Like We Expected in the 1970s?

There are hundreds of hazardous waste sites in the U.S.—but only three have been linked to excess cancers.

Like so many people who fear their health has been damaged by living near a hazardous waste site, the veterans of Camp Lejeune, a polluted Marine Corps base in Jacksonville, North Carolina, have had a long time to wait and stew.

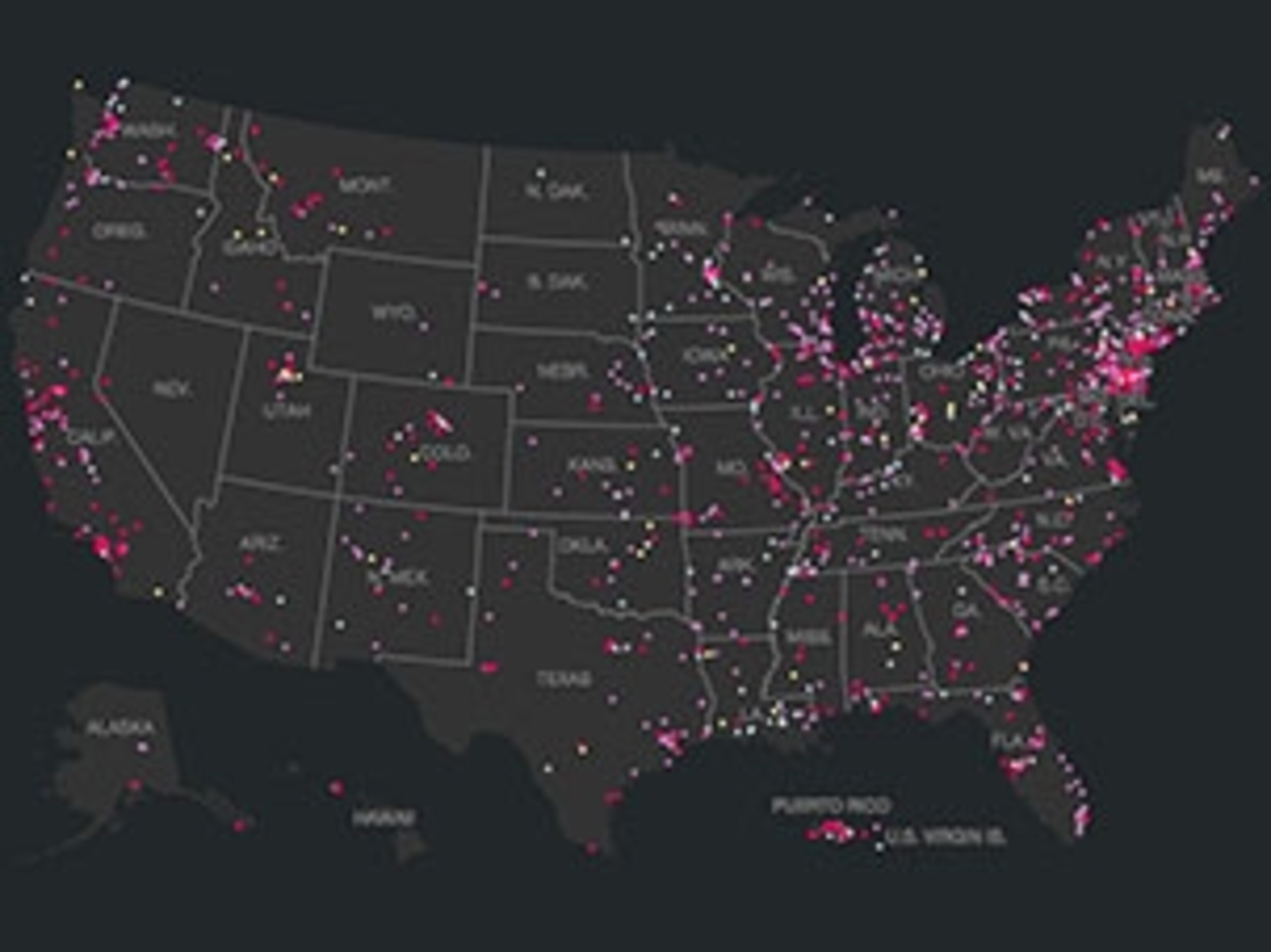

For decades, until 1987, drinking water at the 244-square-mile (632-square-kilometer) coastal camp, home to 130,000 people, was contaminated with gasoline and cleaning solvents. The Environmental Protection Agency listed the camp as a Superfund site in 1989. (Read about the 49 million Americans who live near a Superfund site).

But it wasn't until a decade ago that a group of men who had lived on the base noticed a common thread: Many had developed breast cancer—more than 80 men by one recent count.

They petitioned and raised hell, and soon enough the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took up the case, digging into whether this pollution could have caused their disease. A report is expected next year. (Find out how close you are to a Superfund site.)

If the CDC does find such a link at Lejeune, the camp would join a select few instances where a geographic cluster of cancer cases has been linked to living near hazardous waste.

But nearly 35 years after Congress passed the Superfund law to clean up the nation's waste, only three such clusters have been documented in the United States. Probably the clearest is the cluster of 19 children who contracted leukemia in Woburn, Massachusetts—a story memorialized in the book A Civil Action and in a film by the same name.

A second cluster, involving cases of leukemia and brain cancer among girls in Toms River, New Jersey, may be linked to two Superfund sites nearby, but that link is debatable. And the third cluster, involving pleural cancers among shipyard workers in Charleston, South Carolina, has turned out to be tied more to their exposure to asbestos in their workplace than to the fact that they all lived near a waste site.

Three clusters at most: This is not the cancer wave we expected in the 1970s, when hazardous waste first made headlines.

What happened? Is hazardous waste not as big a deal as we thought? Or is the case against it just too hard to prove? That's still up for debate—but the answer is probably a bit of both.

Outside and Inside Causes

Back in the 1970s, it was common to attribute cancer to external factors, including industrial pollution. Scientists had recently shown the links between smoking and lung cancer, and for a century it had been clear that high doses of chemicals—much higher than you'd get from living near a hazardous waste site—were responsible for cancers found among uranium miners, chimney sweeps, and workers in many other dirty jobs.

When experts back then said that 90 percent of cancer cases likely had some "environmental" trigger, they were including such occupational exposure to chemicals—as well as smoking, obesity, and diet. But many assumed that environmental pollutants such as hazardous waste were also helping lay the foundations of a cancer epidemic.

Decades later, it's still hard to know what the reality is. Two recent books—Dan Fagin's Toms River and George Johnson's The Cancer Chronicles—come down on opposite sides of the question about a potential link between hazardous waste and cancer.

Toms River, published last year, looks at one cluster, wrapping its local story with the history and science of environmental toxicity. Fagin is scrupulous on the science, noting doubts that remain over whether the pollution at Toms River is linked to its cluster, but he is concerned about what science is missing.

It's possible, he notes near the book's end, that by holding cluster studies to high statistical standards, "many more pollution-induced cancer clusters may be out there, but we don't see them and we rarely even bother to look."

Johnson, meanwhile, focuses on dismantling typical fears of pollution, stressing all the internal biological factors that lead to cancer. It's a part of life, he writes. As multicellular organisms age, it's natural for one of their billions of cells to go haywire and start multiplying out of control, creating cancer. While it may be comforting to seek explanations outside ourselves and to assign blame to someone—anyone—cancer is not easy to pin on external villains.

Their views could hardly be more discordant, as Johnson noted in an essay about Fagin's book for Slate last year.

"No matter how hard I squinted at the numbers, I found it hard to be convinced that there had been a cancer problem in Toms River," he wrote. "The tools of statistics, so powerful when applied to large populations, break down with small numbers. As so often in life, we're left wondering how to distinguish between randomness and patterns too subtle to see."

On this much everyone agrees: To the extent cancer clusters are real, they're very hard to prove. Why?

Burden of Proof

The biggest reason is cancer's ubiquity. When 40 percent of Americans will develop the disease during their lifetime, all sorts of patterns are bound to arise by sheer chance. That makes it hard to prove with statistics that one small cancer cluster couldn't be due to chance—and that it must have been caused by a hazardous waste site.

The mobility of Americans makes things even harder: It means a cancer cluster may scatter before it can be identified. "In this country, if you're told that you're living near a [Superfund] site ... the tendency is to get up and leave," says William Suk, director of the National Institutes of Health's Superfund Research Program. That's one reason Suk's researchers have moved their efforts to study cancer clusters to countries like Bangladesh.

Cancer cluster researchers face a host of other challenges, including the fact that the publicity generated by their own investigations makes unbiased data collection difficult. As one recent review of the scientific literature put it, the "nation-wide effort to find environmental causes of community cancer clusters has not been successful."

Find the closest Superfund site near you.

None of this argues that hazardous waste has nothing to do with individual cases of cancer; even if we can't see it, that link could exist.

And none of this argues that hazardous waste isn't dangerous in other ways. Evidence from animal studies indicates that many of the chemicals found in Superfund sites—nasty substances like arsenic, lead, and an array of solvents—may cause birth defects or developmental problems. The contamination at Camp Lejeune, for instance, has been tied to brain and spine defects in children born on the base. But well-documented clusters like that are as rare as cancer clusters.

Accepting Uncertainty

In the face of such scientific uncertainty, the public remains fearful. Concerned citizens flag more than a thousand cases a year of possible clusters to state agencies. Few of these queries will lead to a large-scale investigation. Some of the ones that do will prove a waste of time and taxpayer money.

There is mounting frustration in the scientific world, too, that we've been deploying the same methods with little success for four decades. Last year, that built to a point where experts in epidemiology, biostatistics, chemical exposure, medicine, and risk communication met in Baltimore to rethink how cluster analysis is done. And they found reasons for hope, which they laid out in a recent paper.

For instance, since Americans move so much and cancer is slow to develop, it's long been difficult to find people who may have been exposed to a pollutant—but a lot of personal history can now be found online. Increasing computer power and improved cancer registries could, someday, allow for active monitoring of cancer hot spots, the researchers noted.

And most important, increased understanding of cancer's biology could allow, for example, the detection of biomarkers of cancer even in people who, thanks to good genes, never developed a tumor. That would add data points to a cluster and add evidence that the actual cancers were caused by hazardous waste.

Until those innovations come, it's best to remain cautious on the question of how much hazardous waste has contributed to cancer, Suk says, and to accept that science doesn't have all the answers.

"Sometimes reasonable people struggle to make reasonable decisions," he says. "Sometimes you don't need more data." If your kid and several of his friends all develop leukemia, scientists might very well not be able to prove there's a common cause. But you can still decide to move.