Measles Are Back: Key Questions and Answers on Disease, Vaccinations

Scores of recent cases in California are the most recent in a string of U.S. outbreaks.

The battle against measles in the United States was considered won 15 years ago. Starting in 2000, virtually all new cases of measles came from abroad, and the disease was no longer regularly seen in the U.S. But around 60 people have contracted measles in the U.S. since just last month—most of them at two Disney theme parks in California. Parents of children that are too young to be vaccinated are being told to avoid those parks, and the state's department of health is warning other Californians who are unvaccinated to avoid public places that might draw international travelers.

The outbreak has renewed criticism of the anti-vaccine movement, which is relatively popular in Orange County, where Disneyland is located. At some schools in the county, as many as 60-80 percent of students had missed at least some of their vaccinations.

There have been other scattered measles outbreaks in recent years, including one among unvaccinated Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn, New York, in 2013. Infections usually get carried to the U.S. by people who catch them in other countries—although investigators aren't sure exactly who started the recent outbreak—and then the disease spreads.

As the current outbreak continues, here are some basic questions and answers about the disease and vaccinations:

How do you get the measles?

Measles is "incredibly, incredibly contagious," says David Yassa, an infectious disease doctor at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. It passes through droplets in the air, usually from someone sneezing or coughing, and can blow or linger for a while. Tight spaces like elevators can be points of transmission. Before the vaccine was developed, in 1963, it was extremely common, so most people born before then are expected to be immune.

What are the symptoms?

About eight to ten days after exposure, the person develops a fever, runny nose, and maybe muscle aches. Red eyes are also common. Most patients also have a rash that starts on the face and moves downward and outward, with blotchy red spots that can blend together. The virus's contagious period usually lasts from about four days before the rash starts, and before a person could know he or she has the disease, until four days after.

Measles can be reliably diagnosed if the patient has most of those symptoms plus little whitish spots in the mouth, usually on the gums across from molar teeth. Because the disease has been rare since vaccination began more than 50 years ago, most doctors today have never seen a case of measles.

And then symptoms go away and people are okay?

In most people, the symptoms go away in one or two weeks. In a small number, people can develop pneumonia or neurological conditions that can be life threatening and long lasting. The most vulnerable are children under a year old (who are too young to have been vaccinated); pregnant women; and people with compromised immune systems, such as older adults and those getting treated for cancer.

Until recently, it looked like measles was under control, right?

In 2000 measles were declared eliminated from the United States—"not that we were never seeing any measles, just that there wasn't transmission going on in our country," says Ann Marie Pettis, director of infection prevention at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York, and a board member of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. "We saw primarily isolated cases after that."

In 2013, there were about 175 cases in the United States. In 2014 there were 23 outbreaks in 27 states, accounting for 664 infections, possibly spurred by a large outbreak in the Philippines. Already in 2015 there have been 66 confirmed infections in the United States, and more suspected cases are being investigated.

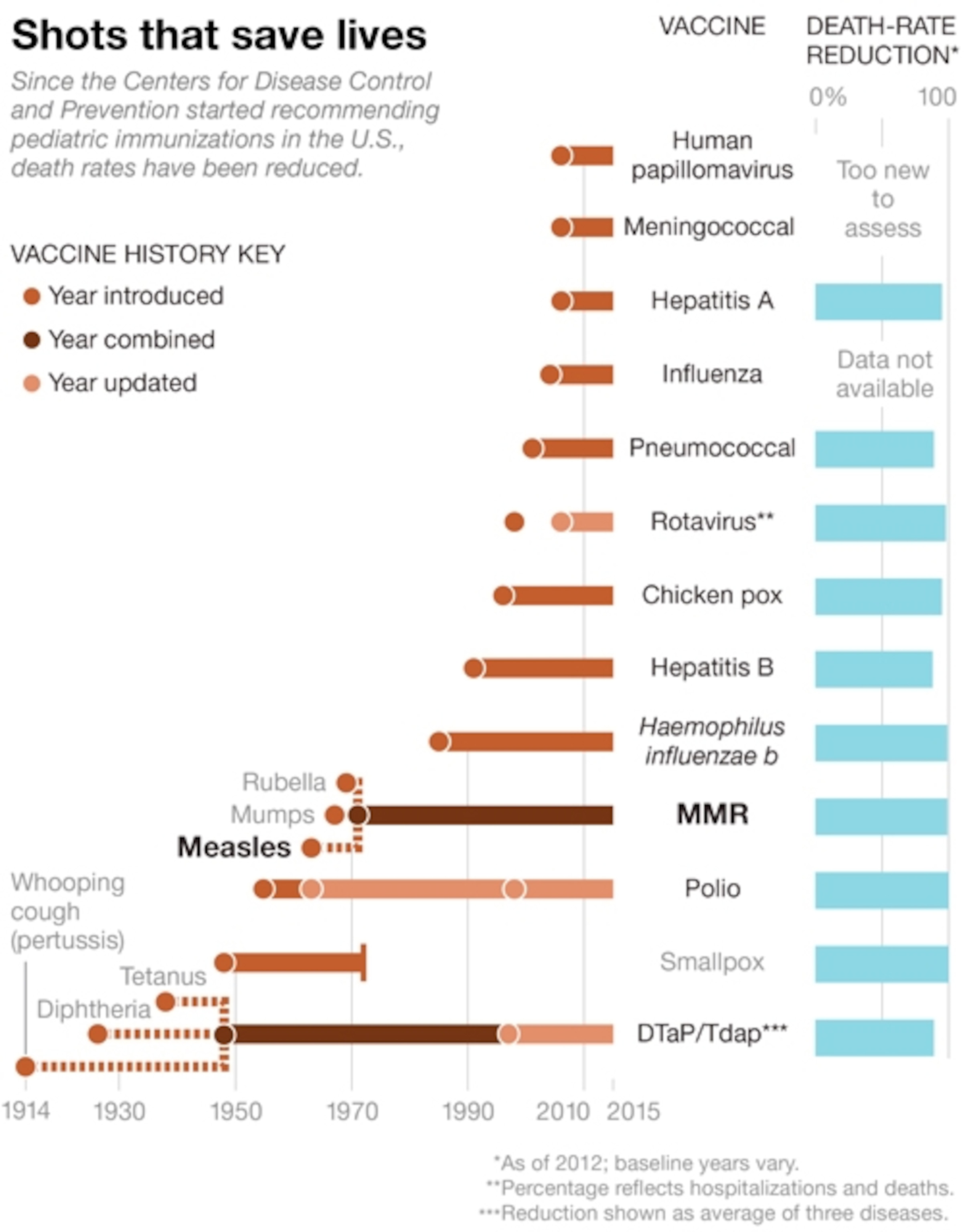

Worldwide, measles deaths reached historic lows in 2012, down to 122,000 from 562,000 a dozen years earlier, according to the World Health Organization. American doctors are strongly supportive of vaccination as the way to cut down on measles.

Were all those who got sick unvaccinated?

Of the 59 Californians who have caught measles since late last year, the state has vaccine documentation on 34 of them, and 28 of those were not vaccinated, including 6 who were too young for the vaccination. Forty-two of the recent cases were directly linked to Disneyland or Disney California Adventure Park. That includes five Disney employees.

Is there anything Disney could have done to prevent or stop this outbreak?

No. Because the virus particles are airborne, nothing Disneyland could have done would have prevented transmission. Anyplace where a lot of people congregate, particularly people from other parts of the world, is potentially vulnerable to measles infection.

Is anyone who has been vaccinated safe from measles?

Most Americans who are older than 51 were exposed to measles in childhood, when the virus was common in the United States, and so developed immunity. Beginning in 1963, children received one dose of the vaccine, which was about 93 percent protective. In the late 1980s, researchers discovered that a second dose bumped the protectiveness up to about 98 percent. Since then, American children have been given two doses, one at 12-15 months and the second no later than ages four to six.

The people who received only one dose, who are now mainly in their 30s and 40s, have slightly less protection than younger or older people. It's also possible that some people, particularly those vaccinated outside the United States, where the supply of vaccine might not have been kept continuously cold, didn't get an effective dose. Doctors may recommend vaccination before traveling overseas to a country where the disease is present.

So did people who refuse vaccination cause the current outbreak?

Most American measles outbreaks have been started by people coming to the U.S. from other countries where the disease is more common, including Europe and the Philippines. Certainly, vaccination helps prevent the spread of disease.

People who refuse vaccines can spread diseases to other people who are unvaccinated or otherwise vulnerable. The most vulnerable groups—babies, pregnant women, and people with compromised immune systems—are also most likely to have bad cases of measles.

Researchers have repeatedly shown no connection between the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and any developmental disabilities. But a portion of the public has been skeptical since a small, now discredited study ran in the journal The Lancet in the late 1990s.

"We're really stuck now," says Yassa, adding that he doesn't know how to reassure people other than with the facts. "The data is very clear in terms of the benefits and lack of risks of these vaccines."

People who choose not to vaccinate their children are taking a risk both for their own child and for the larger community, he says. The more people who are vaccinated, the lower the likelihood that the disease will be passed to someone who is too young to be vaccinated or is otherwise vulnerable to the disease.

Besides vaccination, is there anything people can do to protect themselves?

"What it brings us back to is respiratory etiquette and hand hygiene," says Pettis. Cover your mouth when you cough—with your sleeve not your hand—and wash your hands often, she says. But Pettis strongly supports vaccination. For those who don't want to get vaccinated, Pettis suggests they avoid busy places with international communities, like theme parks and airports.