How Good Old American Marketing Saved the National Parks

Getting people to the parks was the mission a century ago. Now it’s putting visitors to work in the name of science.

When President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill creating Yellowstone in 1872, he established the first national park anywhere in the world. But 40 years later, the parks that exemplified “America’s best idea” were a mess.

“I am now trying to make an extensive study of the tremendous problems that have been coming before me,” admitted Stephen Mather, who was in charge of the parks as an assistant to the secretary of the Department of the Interior, at a meeting he called in March 1915 to address the parks’ troubles.

Although more than a dozen national parks had been designated by then, along with 30 national monuments, the areas functioned with little oversight. “They were orphans,” wrote Horace Albright, Mather’s assistant and key partner in the creation of the National Park Service. “They were split among three departments—War, Agriculture, and Interior. They were anybody’s business and therefore nobody’s business.”

Opportunists hungry for the parks’ natural resources took advantage. Poachers targeted the plentiful wildlife. Ranchers grazed sheep and cattle in mountain meadows. San Francisco boosters even convinced Congress to allow Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley to be flooded as a reservoir for the city’s residents.

Many of these problems weren’t new and national parks conferences had been held before, but the one in 1915, held on the Berkeley campus of the University of California, was different. “This meeting brought everybody together that had anything whatsoever to do with parks,” says Robert Sutton, chief historian of the National Park Service.

The national parks “were anybody’s business and therefore nobody’s business.”Horace Albright, second director of the National Park Service

The solutions were different too. Mather, who had made his fortune marketing Borax soap to the masses, saw the American public as the parks’ savior.

This week, Berkeley—in partnership with the National Park Service and the National Geographic Society—will host a conference on the parks on the 100th anniversary of Mather’s meeting. Influential thinkers like Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell and biologist E. O. Wilson will speak, and the agenda will include how to enlist the masses in saving the parks. This time around, though, the existential threat is more environmental than political.

“True Playgrounds of the People”

Mather first came to Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane’s attention when he sent a fiery letter complaining about the “miserable conditions” in the parks he had visited, including “rundown physical aspects … and dirty unhealthy conditions of lodging, food, and sanitary facilities.”

Rather than taking offense, Lane recruited Mather to head up the Interior Department’s parks office. Albright, a young law student, became his assistant. They both pledged to stay one year.

The parks needed funding and a single agency to be in charge, but according to Albright, Mather felt he “had to get people to use the parks before he could get legislation and appropriations.”

Almost immediately, Mather hired a publicist—Robert Sterling Yard, the Sunday editor of the New York Herald—and paid him with his own money to start selling the parks to the American public. “The parks must be … much better known than they are today,” said Mather, “if they are going to be the true playgrounds of the people that we want them to be.”

Within a month, Mather had summoned the park superintendents to the meeting in Berkeley. He also invited anyone else who had an interest in the parks, purposely including those whose interests were financial.

Railroads had staked their claims to the parks early on, eager to encourage Americans to “See America First” rather than spend vacation dollars in Europe. Now the automobile associations wanted in, lobbying for good roads to smooth the way for drivers. And all those tourists would need decent places to stay and eat.

One of the most influential ideas to come out of the meeting was from Mark Daniels, superintendent and landscape architect for the parks. Pointing out that already in Yosemite Valley “there are times when there are five or six thousand people congregated at one time,” he proposed that each park should contain a village with modern amenities such as “a sanitary system, a water supply system, a telephone system, an electric light system, and a system of patrolling.”

“Mather thought the best way for parks to develop was to get people there,” says parks historian Sutton, “and he wanted to make it as easy as possible.”

The marketing worked. Between 1914 and 1915, the number of visitors to Yosemite alone more than doubled, from roughly 15,000 to 33,000.

The New National Park Service

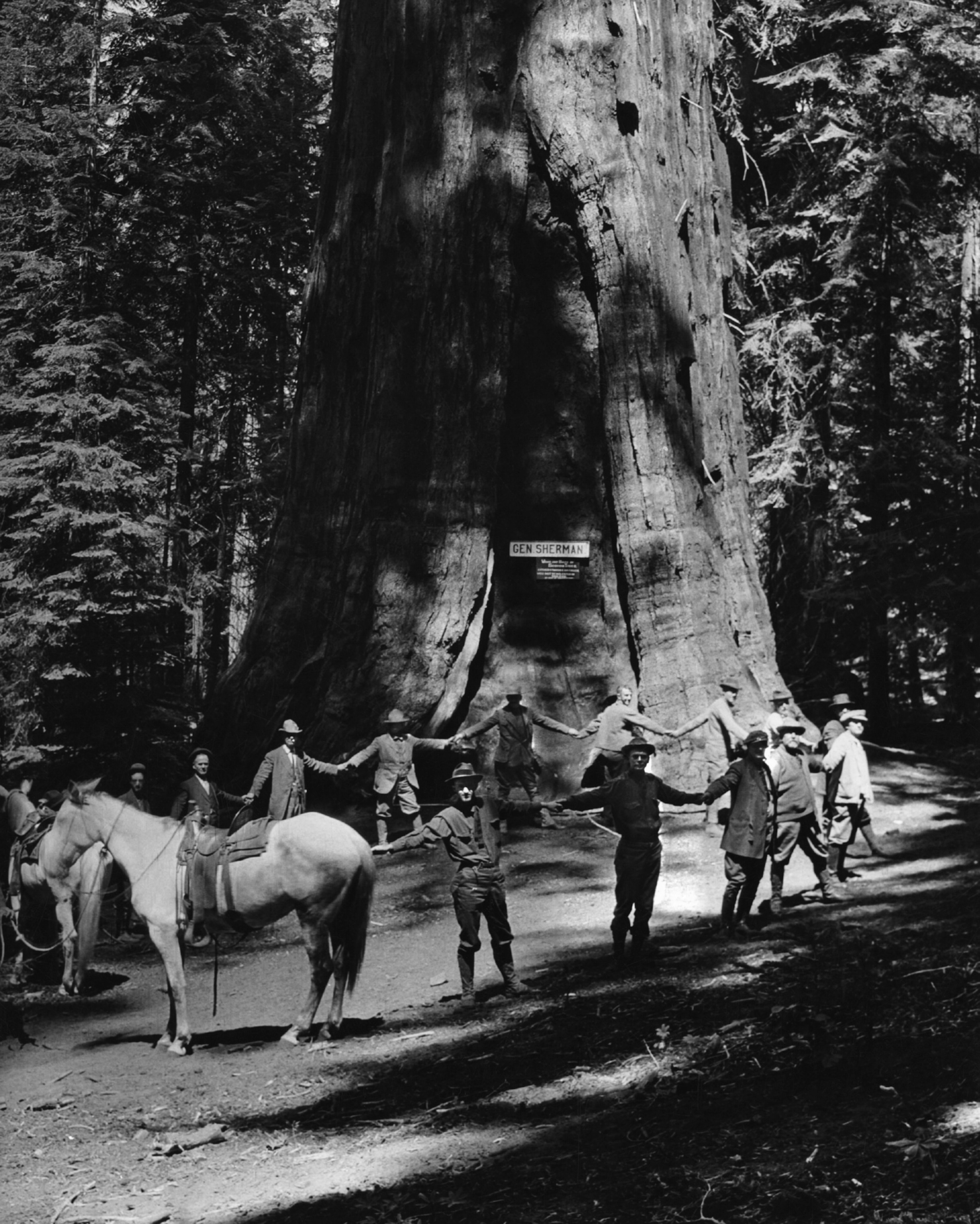

It was a simple equation: More visitors equals more protection for the parks. Mather applied it later that year when he invited 15 influential men, including Gilbert H. Grosvenor, then editor of National Geographic magazine, to travel with him for two weeks through Sequoia National Park.

“Just think of the vast areas of our land that should be preserved for the future,” Mather told the saddlesore gentlemen at the end of the trip. “Unless we can protect the areas currently held with a separate government agency, we may lose them to selfish interests.”

Grosvenor and the others did their part, the editor having pledged during a hike with Mather and Albright that the National Geographic Society would “march in step.” He produced a special issue of National Geographic on the national parks in April 1916—“The Land of the Best”—which ended up on the desks of every congressman in the capital when it came time to vote on a bill to establish a National Park Service.

After many failed attempts over the years, this time the bill made it through Congress. President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Park Service Organic Act on August 25, 1916. Stephen Mather became the agency’s first director, with Albright as his deputy and later successor.

One hundred years later, the parks are no longer a mess, although they face problems that would daunt even Mather. Indeed, the National Park Service reported Monday that the cost of deferred maintenance to park infrastructure reached $11.49 billion in fiscal year 2014.

At this week’s centennial conference, which begins on Wednesday, scientists rather than tourists will be front and center, and the threats they address will include invasive species, pollution, and climate change. Secretary Jewell will be there with Janet Napolitano, president of the University of California, to tie the national parks together with America’s other “best idea”—public education.

If the attendees at this conference are successful, park visitors will be convinced, through activities like BioBlitzes, to become citizen scientists who help expand knowledge of these protected places and become stewards of them in their own right. People are still considered the national parks’ best hope. In the coming century, however, they may be asked to do more than just take in the scenery.

Follow Rachel Hartigan Shea on Twitter.