Super-Spiky Ancient Worm Makes Its Debut

This bizarre new species of 'super-armoured' worm gives us a glimpse into the diverse world of animals living at the roots of our tree of life.

From fantastical to frightening, the animals of the Cambrian period—beginning about 540 million years ago—tantalize the imagination. And they just keep getting weirder.

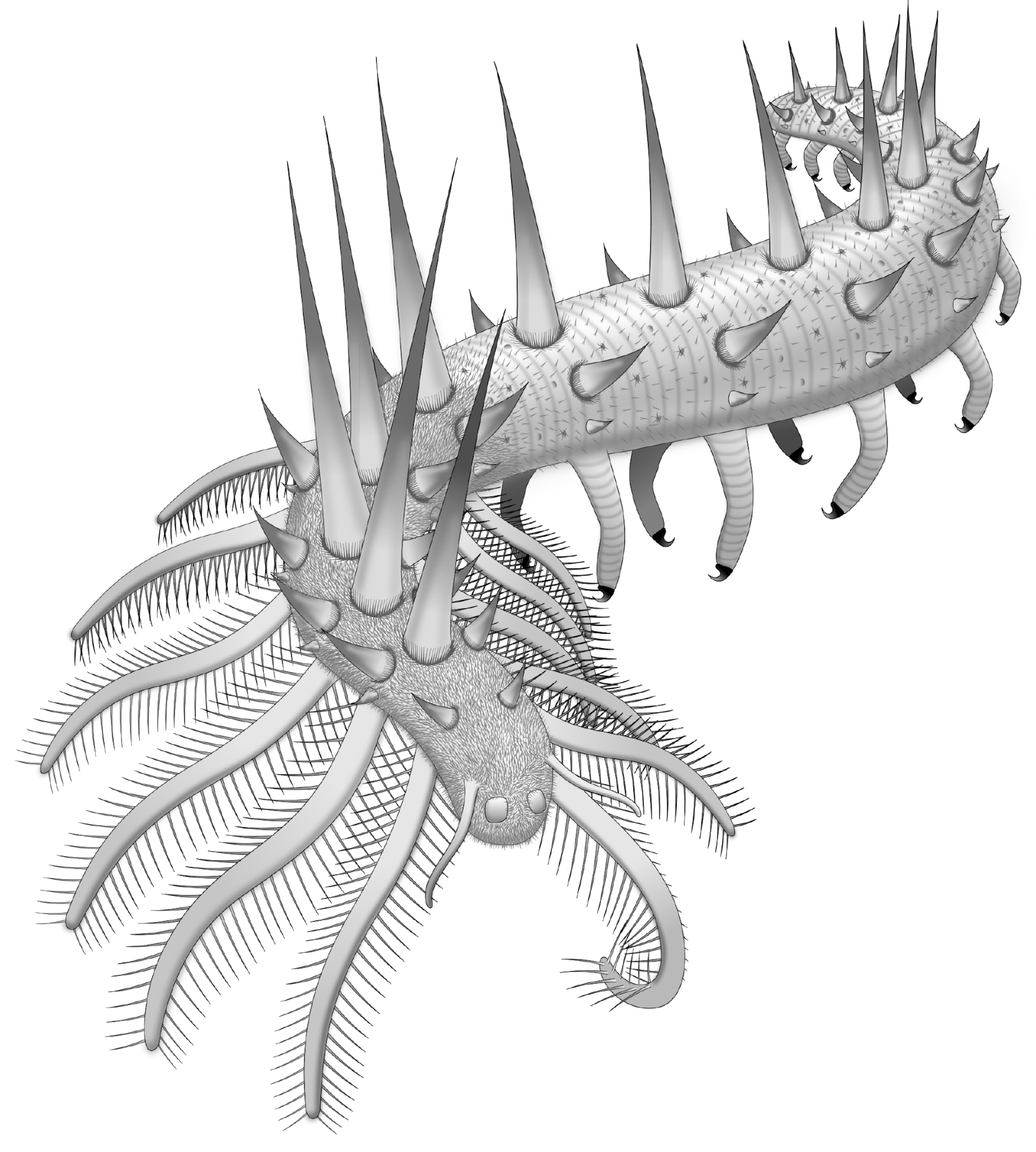

A new species of ancient armored worm was recently discovered trussed up with spikes trailing down its back, two antenna-like appendages on its head, six pairs of feathery forelimbs, and nine pairs of spiny rear limbs that each taper to a strong claw.

This new creature is among the earliest soft-bodied animals discovered that wore armor, showing off the diversity in how these critters looked and lived. The find is documented in a new study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

When you find fossils like this, it makes you rethink the possibilities of how ancient life worked.Marc Laflamme, University of Toronto

Between five and 15 centimeters long, the spiky monster hails from a newly discovered trove of fossils in Southern China that yielded nearly 30 exquisitely preserved specimens. The creature closely resembles a yet-to-be-identified fossil that paleontologist Desmond Collins discovered in the '80s, earning this new species the moniker Collinsium ciliosum, or "Collin's monster."

Collin's monster is a close relative of Hallucigenia—another spiky oddball named for its "bizarre and dreamlike quality"—but has even more spines and specialized limbs for feeding. The creature is like "Hallucigenia on steroids," says Javier Ortega-Hernández, a paleobiologist at the University of Cambridge and one of the lead authors of the study.

"This is a very peculiar animal," says Ortega-Hernández, whose first reaction upon seeing the little monster was, "Oh wow, that is—different."

It took 40 years for scientists to figure out which end of Hallucigenia was the head, but the Collin's monster fossils were so well preserved that there was no question of heads or tails. In some of the specimens, even the digestive tract remained. (For the latest on Hallucigenia, see "Scientists Finally Decide Which Bits of this Weird Animal is the Head.")

Family Ties

Both Hallucigenia and Collin's monster are ancestors of the modern velvet worm, a colorful, terrestrial, caterpillar-like worm that spits slime at its prey.

But with such distinct styling compared with modern velvet worms, it's hard to see the resemblance. The secret is in the claw.

Velvet worms and many of their relatives—including Collin's monster and Hallucigenia—have claws (and spines) that work like Russian nesting dolls, explains Ortega-Hernández. Each claw has a smaller claw inside, which contains an even smaller claw, and so on.

Endless Possibilities

Though modern velvet worms are "really cute," says Ortega-Hernández, they all live similar slime-spitting lifestyles. They are a "bit of a one-trick kind of pony. They do one thing very well, but that's all they do."

This isn't true for the worm's ancient relatives, who fed and lived in many different ways—whether floating in the water or scrounging in the mud.

Fossils such as Hallucigenia and Collin's monster are "golden tickets" to understand the vast diversity at the root of the animal tree of life, explains Marc Laflamme, paleontologist at the University of Toronto, who wasn't involved in the study.

Collin's monster is thought to have lived in the deep ocean. Using its clawed hind legs to affix itself to a stable object—sponges, coral, rocks—it probably created currents with its feathery forelimbs to draw tasty bits of organic debris or tiny animals into its mouth.

Since this could be a dangerous lifestyle for an animal that is "soft and squishy and probably quite delicious," says Ortega-Hernández, Collin's monster donned a suit of spiky armor.

Yet over time, both competition and extinction events—whether from drastically changing temperatures or meteor impacts—made each ecological niche prime real estate, and diminished the exciting and bizarre diversity.

Many species alive today, including crinoids and brachiopods, follow this same pattern.

"When you find fossils like this, it makes you rethink the possibilities of how ancient life worked," says Laflamme.

Follow Maya Wei-Haas on Twitter.