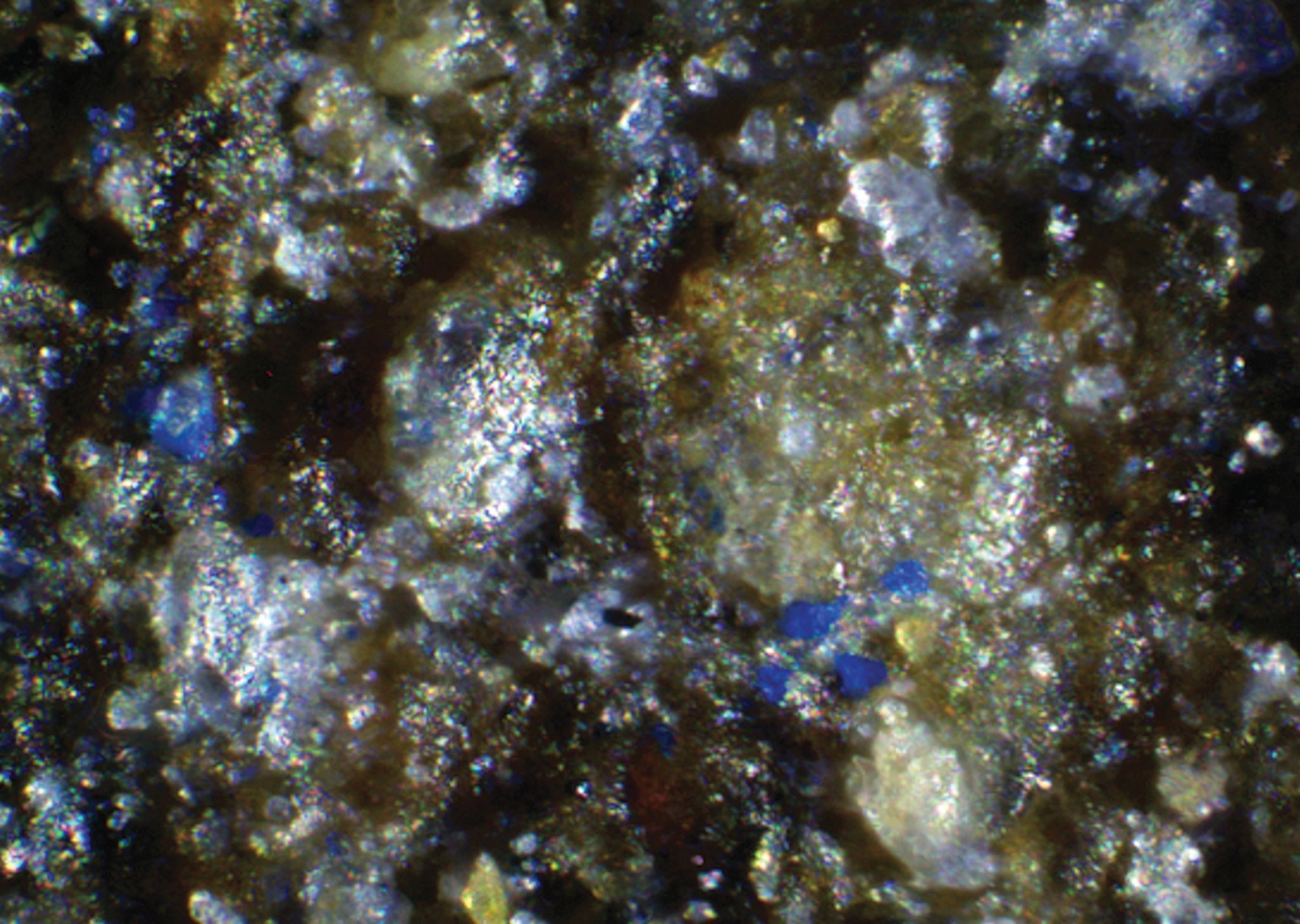

This is the oldest blue pigment ever discovered in Europe

The discovery of a stone long overlooked in a German museum suggests that Ice Age communities experimented with vivid hues far earlier than scholars believed.

For the past 50 years, a small, unremarkable stone sat on display at a museum in Germany. Archaeologists excavated the stone in the late 1970s from a German site called Mühlheim-Dietesheim. It was believed to be a simple oil lamp from the end of the last Ice Age during the Upper Paleolithic period, around 10,000 to 50,000 years ago. Researchers now say the stone contains traces of a blue residue dating to roughly 13,000 years ago—predating the earliest known use of blue pigment in Europe by approximately 8,000 years.

Compared to other natural pigments, blue has a relatively young history. The only other known example of blue in the Paleolithic is on figurines found in modern Siberia, but researchers didn’t identify what type of pigment created the color. Another study found evidence that roughly 33,000 years ago, people were processing a plant that can be used to make natural blue dye as well as medicine at a site in Georgia, but there was no evidence of either. Blue was completely absent from the Paleolithic palette, which relied almost exclusively on red and black hues.

“This is actually one of the rare examples when we were completely surprised by the discovery,” says archaeologist Izzy Wisher from Aarhus University in Denmark, lead author of a paper on the finding published September 29 in the journal Antiquity.

(Barbie’s signature pink may be Earth’s oldest color.)

A colorful copper mineral

Wisher’s colleague Felix Riede, also an archaeologist at Aarhus University, was reexamining a few objects previously excavated from the site, including the stone. If it was indeed a lamp, he thought it might contain traces of animal fat. Wisher has knowledge of Paleolithic art and pigments and lighting technologies used in the Upper Paleolithic, so he looped her in.

“As we were looking at this lamp, we noticed that there were these very small traces of blue residue on the object, and at first we joked that it might be some modern kind of ink that got onto it,” Wisher explains.

The animal fat analysis was inconclusive, and a series of coincidences and curiosity led them to look more at the blue residue. With help from geoscience colleagues, they figured out that the pigment contained copper and eventually identified it as a mineral called azurite.

Rocks near the archaeological site contain azurite, and the mineral’s chemical fingerprint suggests it came from the area. In this region of Germany, archaeologists have also uncovered evidence that people mined for two other minerals, flint and a red pigment called ochre, during the same period. Wisher’s team's theory is that people likely came across the mineral while mining for these other resources and extracted it similarly to how they were extracting ochre and flint. Small fragments of ochre from the site support this idea.

“The most interesting part of this research is that this object is quite unremarkable,” Wisher says of the stone originally believed to be a lamp. “Our feeling now is that this category of object needs to be reexamined in light of this paper to see whether some of these so-called lamps were instead used for pigment processing.”

Elizabeth Velliky, an archaeologist at the University of Bergen in Norway who studies the relationship between mineral pigment use and early human cultural evolution, expression and symbolism, calls the discovery “the tip of the iceberg” in what we know about how people used pigments in prehistory.

“I do think that the past was more colorful than we originally thought, but now we actually have evidence for it,” says Velliky, who was not involved in the study. At this time, people in Europe were forming more complex social groups, and those in different regions were developing different ways to use stone tools, she explains.

It’s not too much of a leap to think that they might have experimented with color at the same time they were experimenting with stones. “The population is increasing in Europe, the glaciers are retreating. So people are moving around more. There's probably more communication and they probably need more or would like more ways to express themselves—whether that's for social identity, group affiliation or personal reasons,” Velliky says.

Why don’t we see more blues in the Paleolithic?

It’s unclear exactly how people used the color blue and what it signified, but Wisher and her colleagues have some theories.

“If azurite was so abundant in the local landscape and they had methods to extract it, why do we not see more of it in the archaeological record from this period? We think that this is probably because azurite was used for archaeologically invisible activities that don’t preserve, such as decorating the body or dying fabrics,” Wisher says.

Naturally occurring pigments require time and energy to extract and turn into dyes or paints. All that effort suggests blue carried cultural significance. The find also challenges previous research that suggested the colors we see in Paleolithic art are a product of the colors that they could access.

“Instead of this being a simple narrative that they couldn't access certain colors,” says Wisher, “this seems to paint a picture of Paleolithic people being very selective about the colors they used for particular activities and the visual effects they wanted to achieve."