What destroyed Napoleon’s army? Scientists uncover new clues.

A new genetic analysis of teeth from a mass grave in Lithuania reveals hidden illnesses that plagued the French emperor's soldiers during their disastrous 1812 retreat.

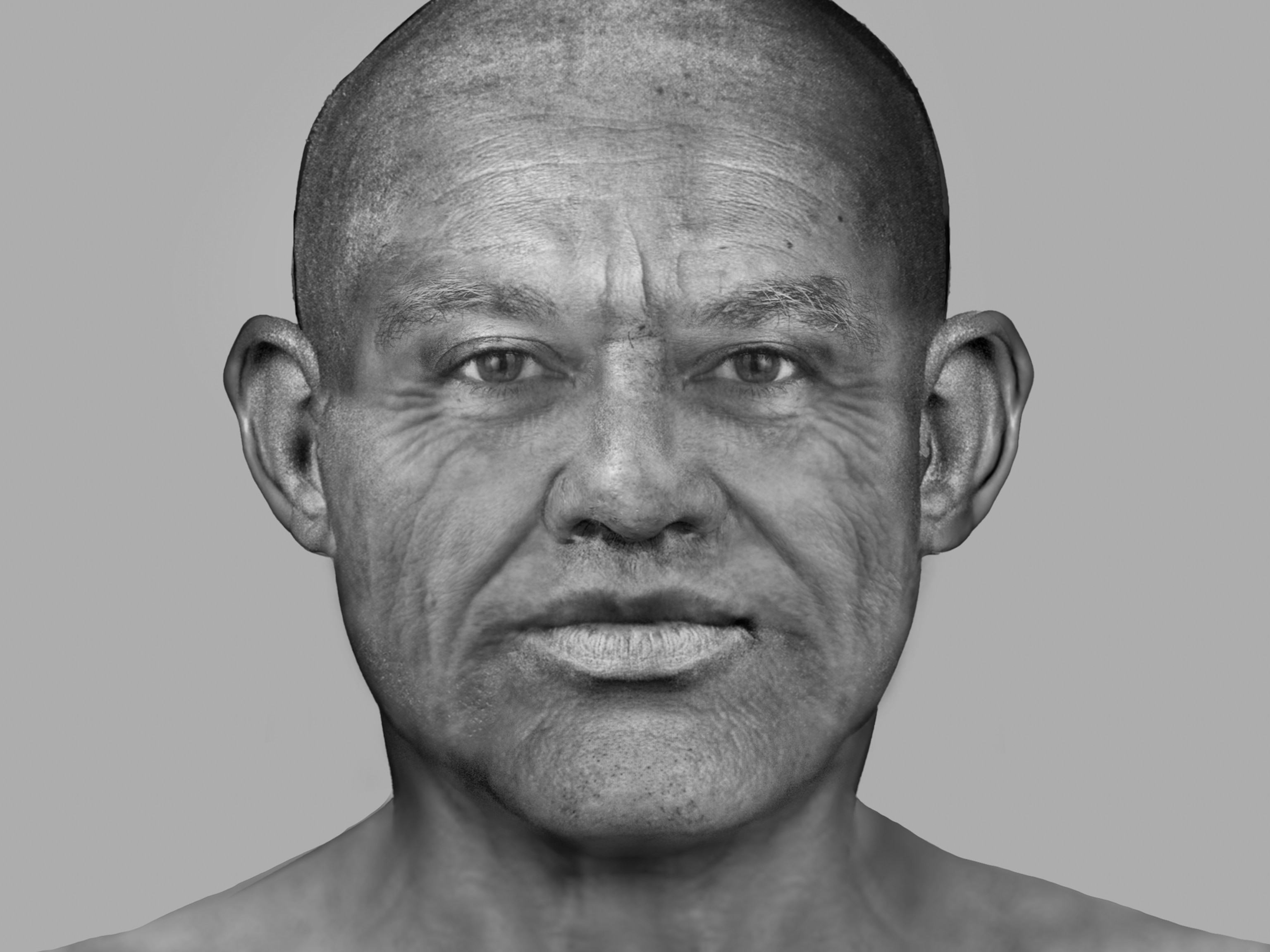

As French general and ruler Napoleon Bonaparte returned from a disastrous attempt to conquer Russia in 1812, his army lost tens of thousands of men—many of them conscripted by force—to a fatal combination of extreme cold, exhaustion, starvation and disease.

Based on reports from the time, the main diseases thought to have caused their demise were “camp fever,” known today as typhus, and “trench fever.” Yet, when researchers recently analyzed ancient DNA from 13 teeth collected from different soldiers buried in a mass grave in Vilnius, Lithuania, they were surprised when they did not find evidence of either scourge.

Instead, they discovered DNA traces of two different bacteria, suggesting that Napoleon’s army was under siege during its retreat from more pathogens than previously thought. The findings were published Friday in the journal Current Biology.

“To be honest, we decided to work on those samples because we expected to find typhus, so this was quite surprising,” says Nicolás Rascovan, a paleogeneticist from the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and lead author on the study. “But the best results are the most unexpected.”

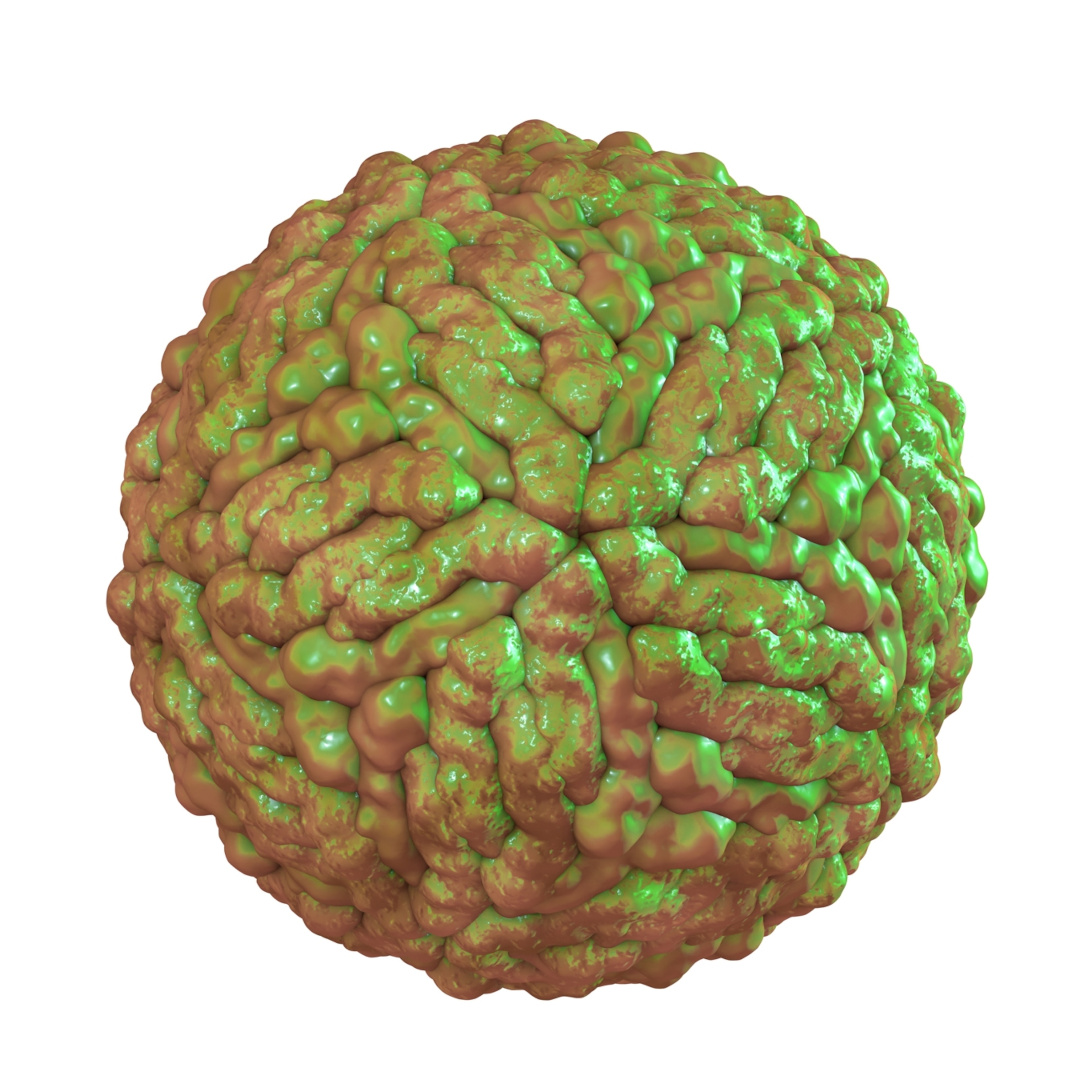

One of the pathogens the team found was a species of Borrelia—a relative of the tick-borne bacteria that cause Lyme disease. It is spread by lice and triggers a debilitating illness known as ‘relapsing fever’ that is now rare in Europe.

The other was a strain of Salmonella that causes a condition called paratyphoid fever. Though it has similar symptoms to typhus, like fever, rashes and diarrhea, it is not spread by lice like typhus is. People tend to get infected by it from consuming water and food polluted by fecal matter.

Alexandra Buzhilova, an anthropologist from the Lomonosov Moscow State University, who took part in an earlier study of the teeth of Napoleonic soldiers buried in Kaliningrad, Russia, but not this one, says she was “intrigued” that the researchers were able to identify two previously undocumented pathogens.

“This is further evidence that ancient DNA sequencing is a powerful approach for investigating historical disease,” she says.

Pathogens trapped in teeth

Given that the researchers analyzed the teeth of only 13 individuals out of more than 3,000 in the mass grave, Rascovan cautions that the findings do not mean that these two pathogens were a major cause of death, or that typhus was not. Instead, he says, his team’s results offer insight into other diseases that may have contributed to their ill health and perhaps even death.

(The Death of Napoleon' captures the end of a tumultuous era)

“I suspect this study will open the door to more observations of bacterial species that caused fever in the past,” says Lucy van Dorp, a geneticist from the University College London. She was not involved in this study but was part of the teams that uncovered relatives of both of these bacteria in other locations.

Rimantas Jankauskas, an osteologist from Vilnius University, who led the Lithuanian team that studied the remains found at the cemetery, says he regrets he was not informed about or involved in the new study. But he agrees the new findings do not exclude typhus as a major cause of death. Rather, he says, the finding “adds more details on the tragedy that took place in December 1812.”

Napoleon's 'big mistake'

Joseph Romain Louis de Kirckhoff, an army doctor who in 1836 published a book about his experiences treating people during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, described the hospitals in which the sick and wounded ended up as ‘cesspools of misery and infection.’ He thought the illness arose from filthy clothes, bad food, exhaustion and overcrowding. In one intriguing passage, he also blamed the incessant diarrhea on the fermented beets soldiers were appropriating from local houses.

“I was reading the old report of this doctor and thought it was very interesting that he wrote about this, because it’s very rare to have a hypothesis on the source of infection,” says Rémi Barbieri, a microbiologist also from the Pasteur Institute in Paris and coauthor on the study.

(Was Napoleon even short? Inside the history of discrimination against short men)

Barbieri read many contemporary texts on the matter. But he and his colleagues think it’s at least equally likely that it was their own lack of hygiene that made them sick.

Back in 1812, it wasn’t yet known that infectious diseases were caused by micro-organisms. Most experts believed that diseases spontaneously arose out of filth and then spread via ‘foul air,’ which was shown to be wrong decades later by Louis Pasteur, founder of the institute Rascovan and Barbieri work at. Yet de Kirckhoff did notice that many people in the town of Lyozna fell ill after the army arrived.

And after the survivors left Vilnius, the suffering was far from over.

“Everywhere we passed during the months of January and February, we brought panic and death,” de Kirckhoff wrote, and the local inhabitants, “forced to lodge and feed us, were not only crushed by our passage, but became the prey of a murderous contagion, a fatal present that we gave them.”

(Napoleon lost the Battle of Waterloo—here’s what went wrong)

Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion still stands out to historians as a monumental and pointless—though by no means unique—waste of human lives in a misguided and cruel leader’s quest for personal glory. J.R.L de Kirckhoff, who himself became a lifelong defender of public hospitals and healthcare for the poor, called it “a big mistake,” and something “no man of good faith would dare attempt to justify.”