How NASA's Cassini Spacecraft Met Its Fiery End

After 13 years exploring Saturn, the probe went deep into the planet’s atmosphere for its explosive grand finale.

PASADENA, CALIFORNIA — In the predawn hours on Friday, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft boldly went where no spacecraft has gone before: into the planet Saturn itself.

As the spacecraft raced toward its end, scientists in mission control at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena watched the drama play out.

Of course, they all knew the ending.

After more than a decade exploring Saturn and its menagerie of moons, the spacecraft dove through the planet’s atmosphere, scooping up data as it fell and sending science back to Earth for as long as it could.

Then, the spacecraft’s thrusters failed, overwhelmed by gravity and intense atmospheric friction. It began to tumble, lost sight of Earth, and went silent forever around 4:55 a.m. PT.

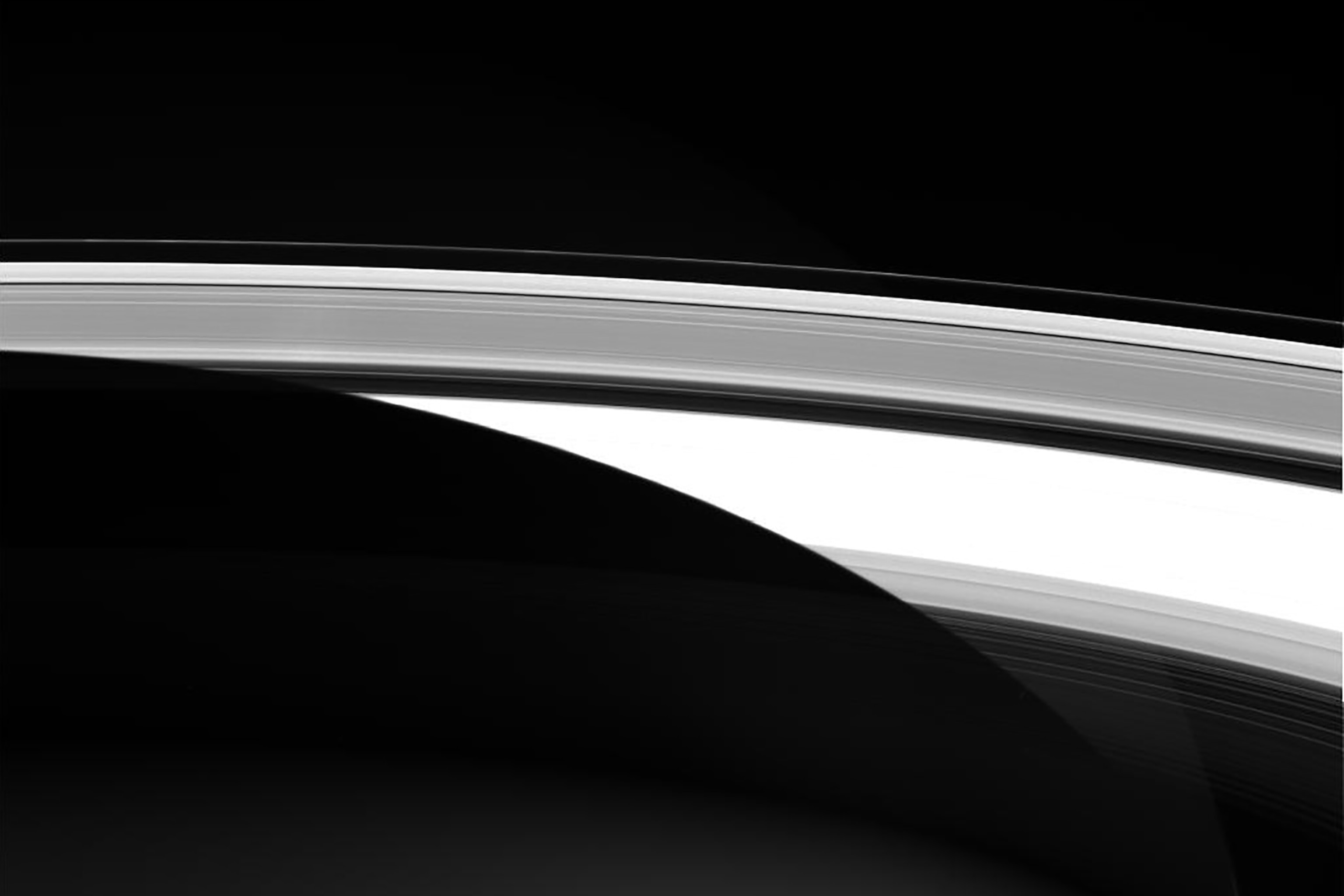

Though scientists couldn’t observe the action, they knew that one or maybe two minutes after Cassini’s signal vanished, Saturn tore the spacecraft apart. The probe shed flaming pieces into the planet’s atmosphere, streaking through the alien sky like a crumbling meteor.

Its end was quick. Cassini, which taught us so much about Saturn and its moons, was no more.

“I stood there with a mixture of applause and tears,” says project scientist Linda Spilker. “It felt so much like losing a friend, a spacecraft I’d gotten to know so well.”

Across town, nearly 2,000 Cassini team members and their families gathered at Caltech to watch a live feed of the loss of signal.

“This is a celebration of an amazing mission and an incredible legacy,” said team member Morgan Cable.

Fond Farewell

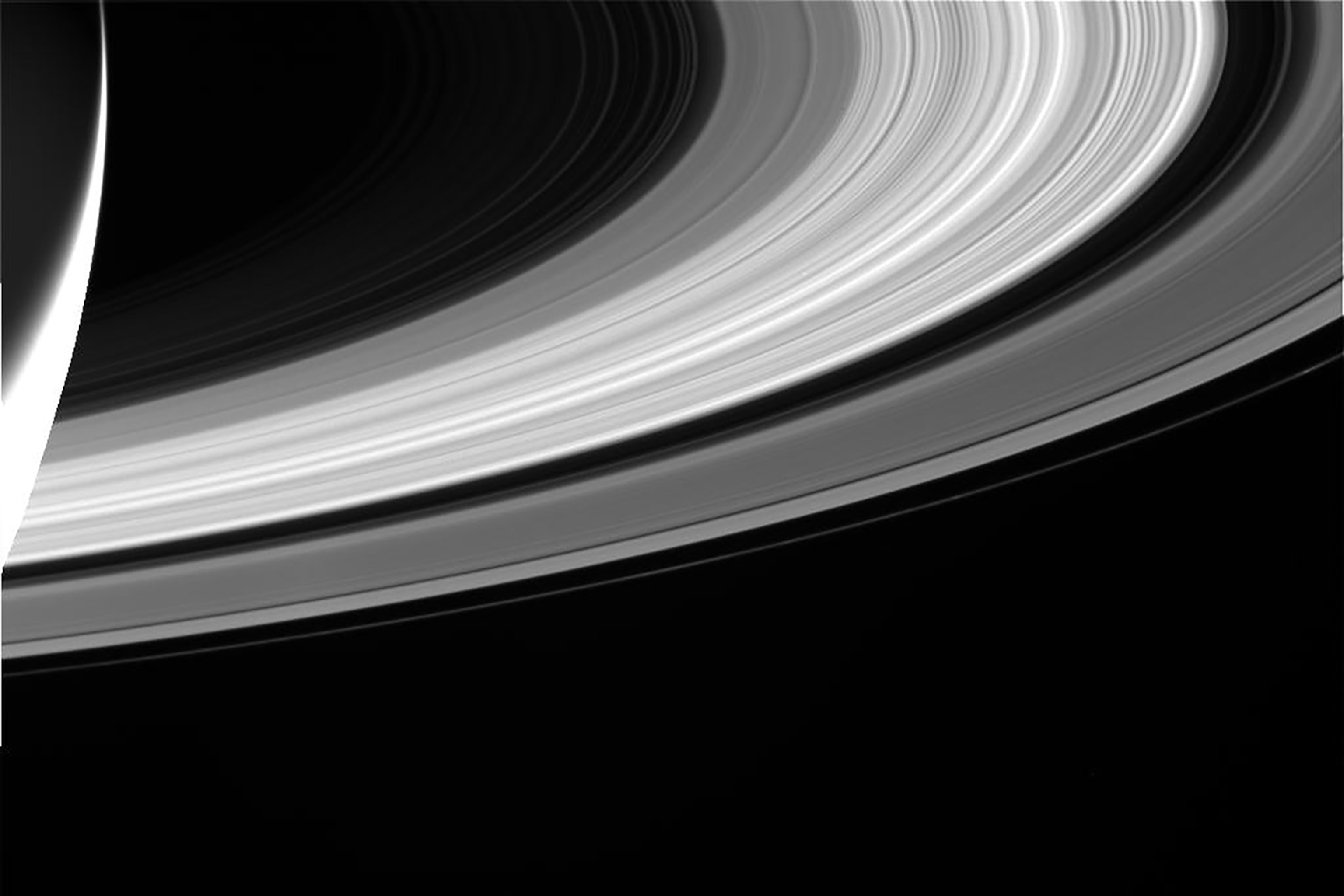

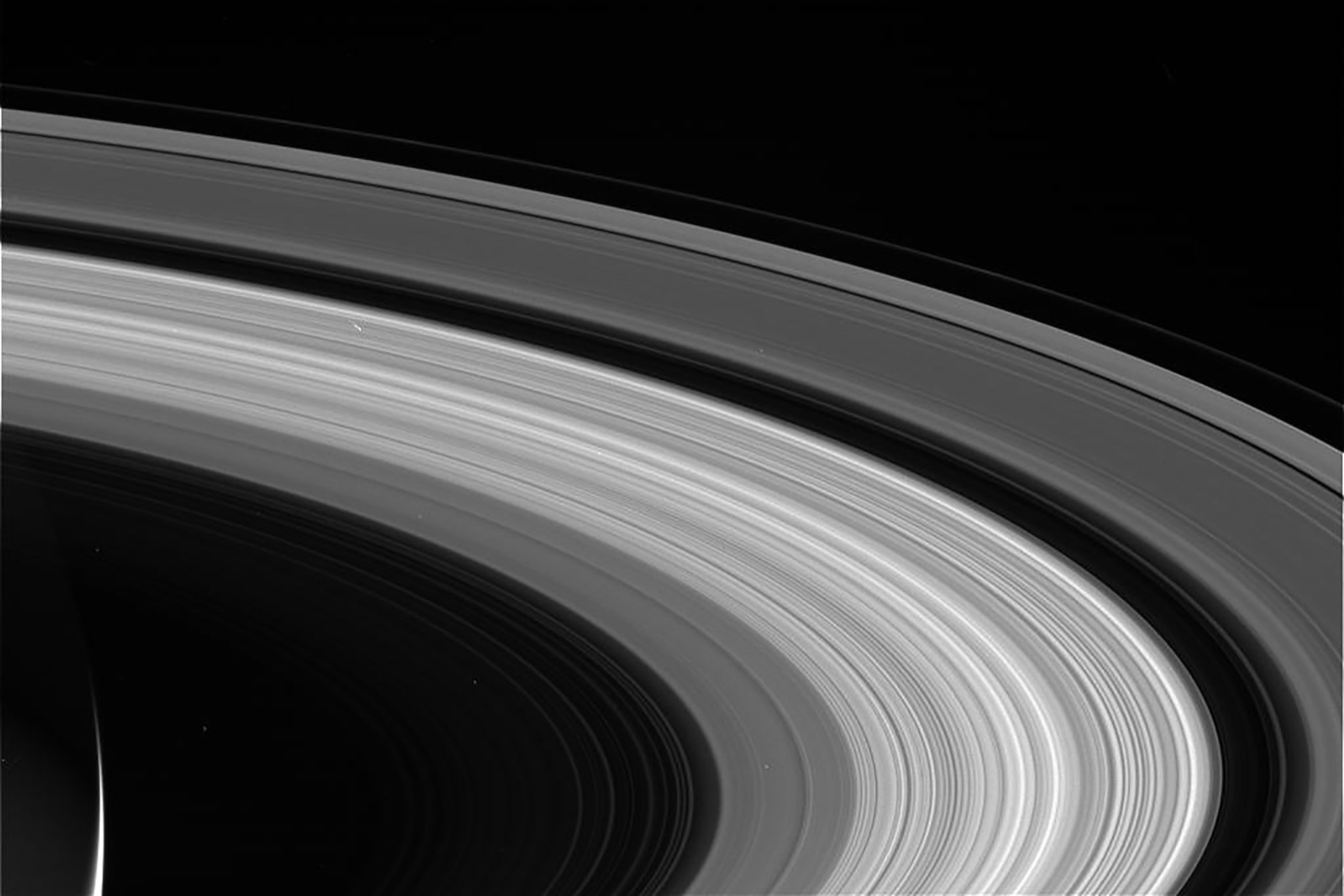

In 2004, Cassini began exploring the Saturn system. For more than 13 years, it swiveled, flipped, and flew around the ringed planet and its many moons, executing millions of commands and beaming more than 450,000 images back to Earth.

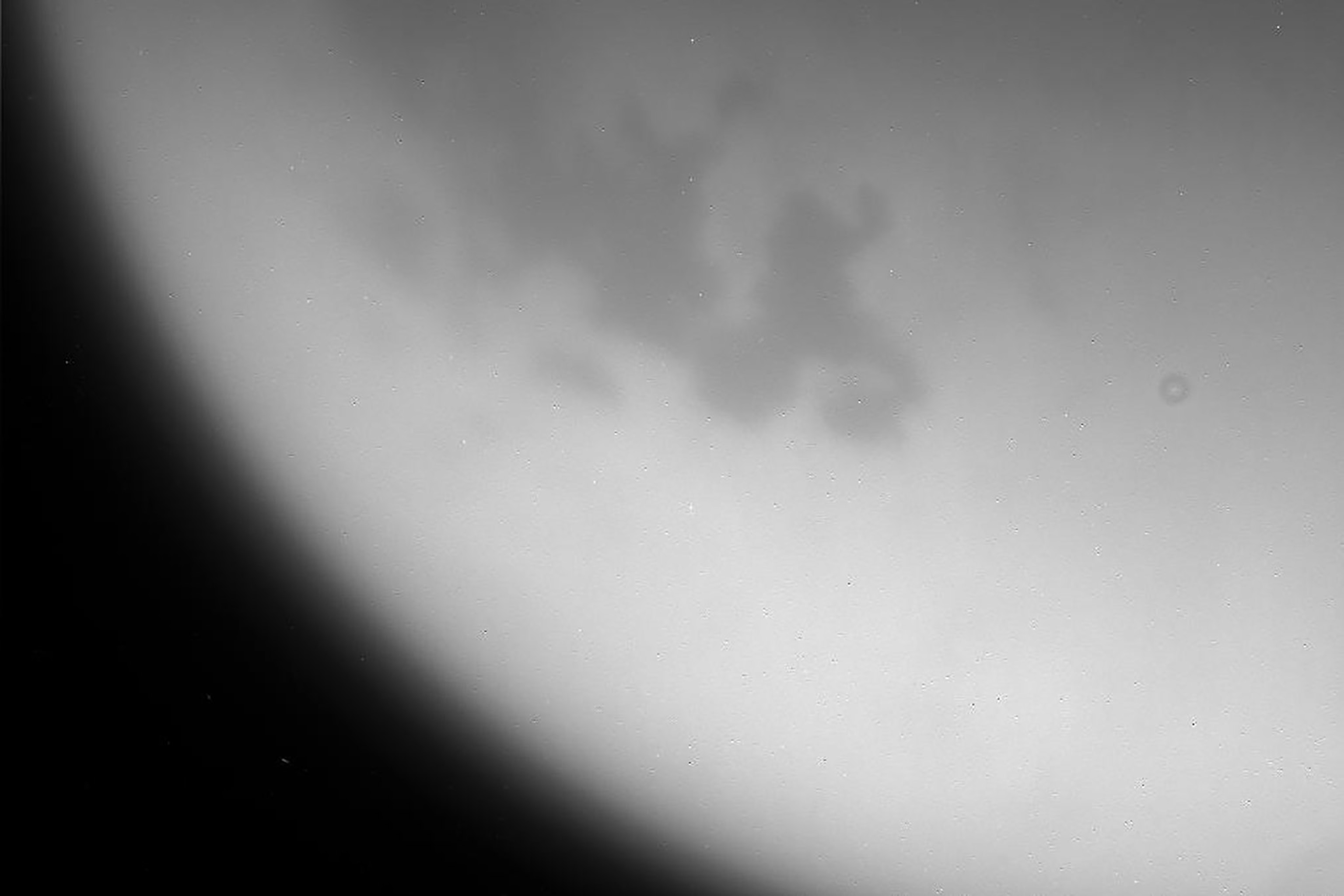

Early on, Cassini dropped the Huygens lander onto hazy, orange Titan. The second largest moon in the solar system, Titan is shrouded in a thick nitrogen atmosphere that hides its oily lakes and seas from view. Now, thanks to Cassini, we know that Titan is among the best places to look for life beyond Earth.

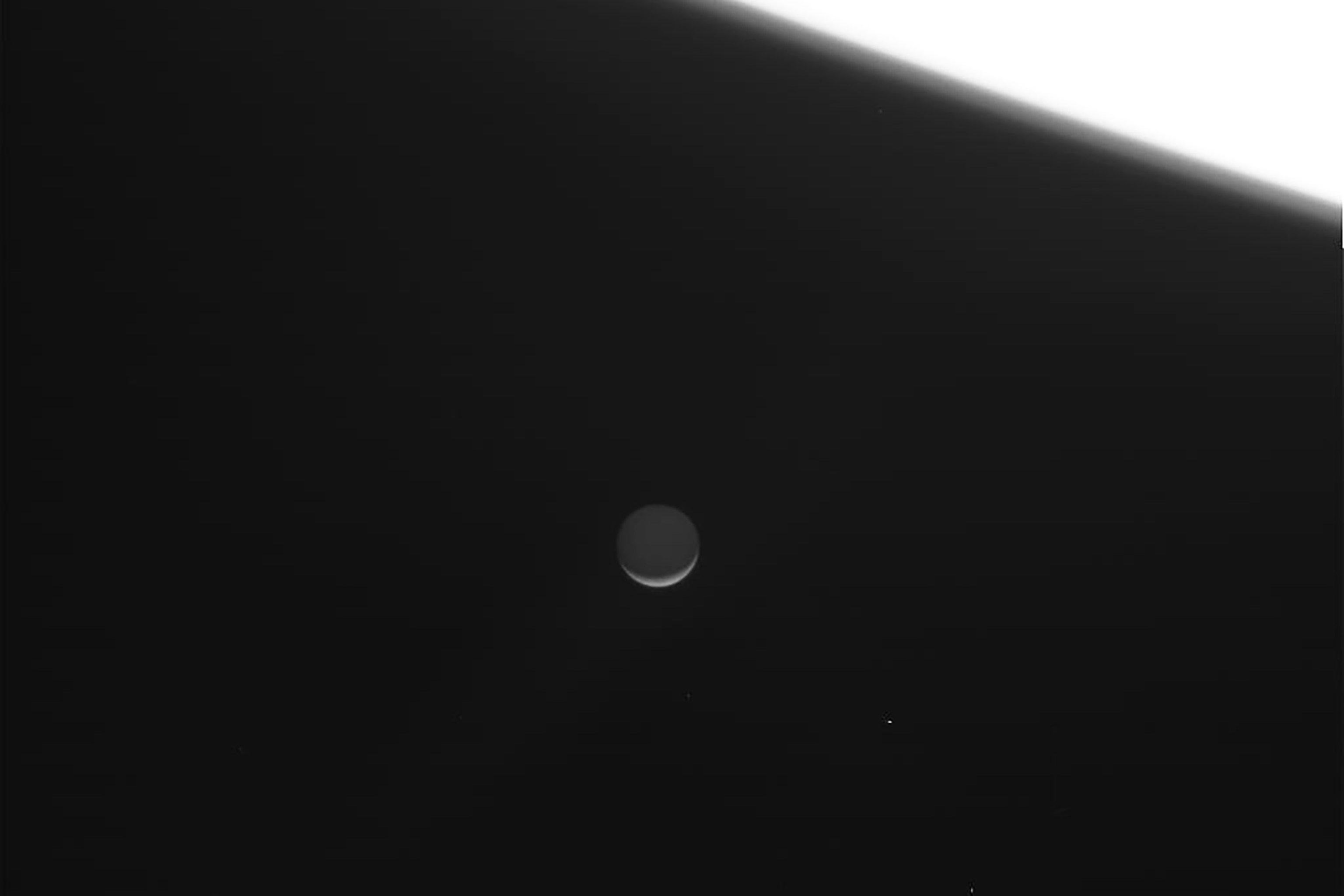

Not long after, Cassini spotted enormous geysers erupting from fissures at the south pole of tiny Enceladus, an icy moon harboring a hidden, global ocean. Like Titan, Enceladus is now considered one of the most likely places to find alien life in the solar system—and these two moons are the reason Cassini can’t stay in orbit around Saturn forever.

The spacecraft’s fuel reserves are dry, and leaving it looping around the Saturn system with no way of controlling it risks an unplanned crash into one of these tantalizing worlds. Despite knowing that destroying Cassini is the best thing for science, plenty of people are mourning the end of the beloved mission.

“I loved the fact that every morning I could go to my computer and have a quick look at the latest images downloaded from the spacecraft,” says Carl Murray of Queen Mary University of London. “It was almost like having your own webcam keeping an eye on conditions at the other side of the solar system!”

Indeed, as the spacecraft’s demise drew closer, social media platforms filled with laments—including the perpetual screaming of a Twitter account that just couldn’t handle the probe’s impending doom.

Curtain Call

On September 11, a gravitational nudge from Titan set Cassini on a collision course with Saturn. From then on, its final chapter was written.

Around 1 p.m. PT on September 14, Cassini took its last photos, a set of images highlighting the moons Titan and Enceladus, and Saturn itself. It then began transmitting information continuously to scientists back on Earth.

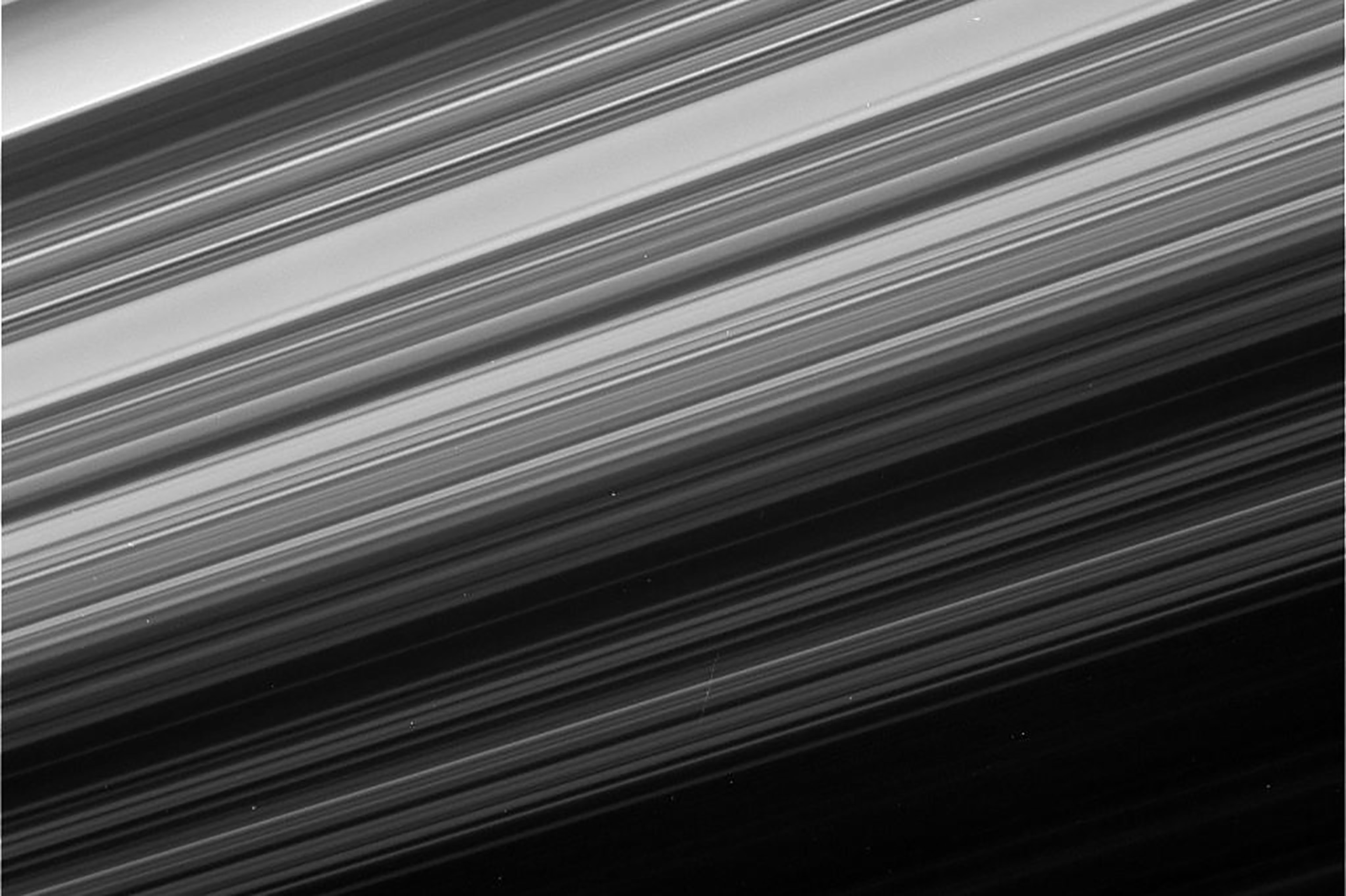

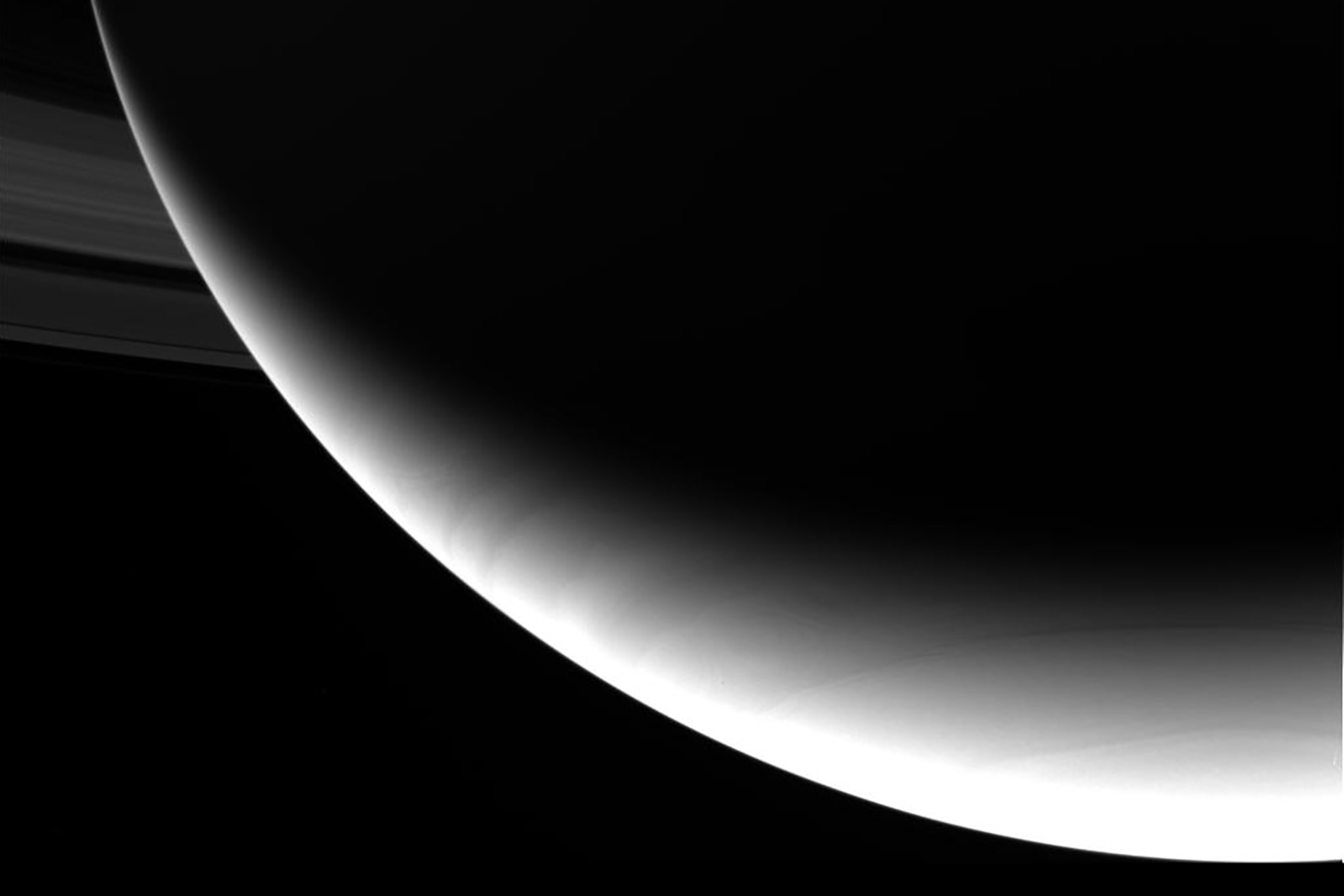

When it began its plunge through the planet’s cloud tops around 3:30 a.m. on September 15, it was behaving like an atmospheric probe, breathing in as much of the alien atmosphere as it could and exhaling data as quickly as it inhaled.

Eventually it ignited and broke apart in Saturn’s sky. Because of the time it takes signals to travel between Saturn and Earth, by the time Cassini’s last whisper arrived at mission control, it had already been dead for 83 minutes.

For the many scientists and engineers who worked on Cassini, the sadness in the room was tangible. But there was also pride in a mission that had accomplished so much, and hope for a future that could again see a spacecraft soaring over Saturn’s rings.

Until that day, though, the Saturn system and its mysteries will wait to be unlocked by the next robotic ambassador from Earth.

“This morning, a lone explorer, a machine made by humankind, finished its mission 900 million miles away,” said Cassini program manager Earl Maize. "Thanks, and farewell, faithful explorer."