Chernobyl's Mutated Species May Help Protect Astronauts

Some species in the radioactive site show resistances to radiation—and their genetic protections may one day be applied to humans.

On the big screen, astronauts face many dangers, from explosions, to suffocating in the vacuum of space, to maniacal red-eyed sentient computers. But perhaps the deadliest threat to real astronauts is one they can’t even see: radiation.

Our planet’s magnetic field generates a protective bubble, called the magnetosphere, that shields the surface from damaging cosmic radiation. Humans traveling beyond this bubble will be subjected to dangerous cosmic rays and solar storms, which can damage cells and cause changes in DNA.

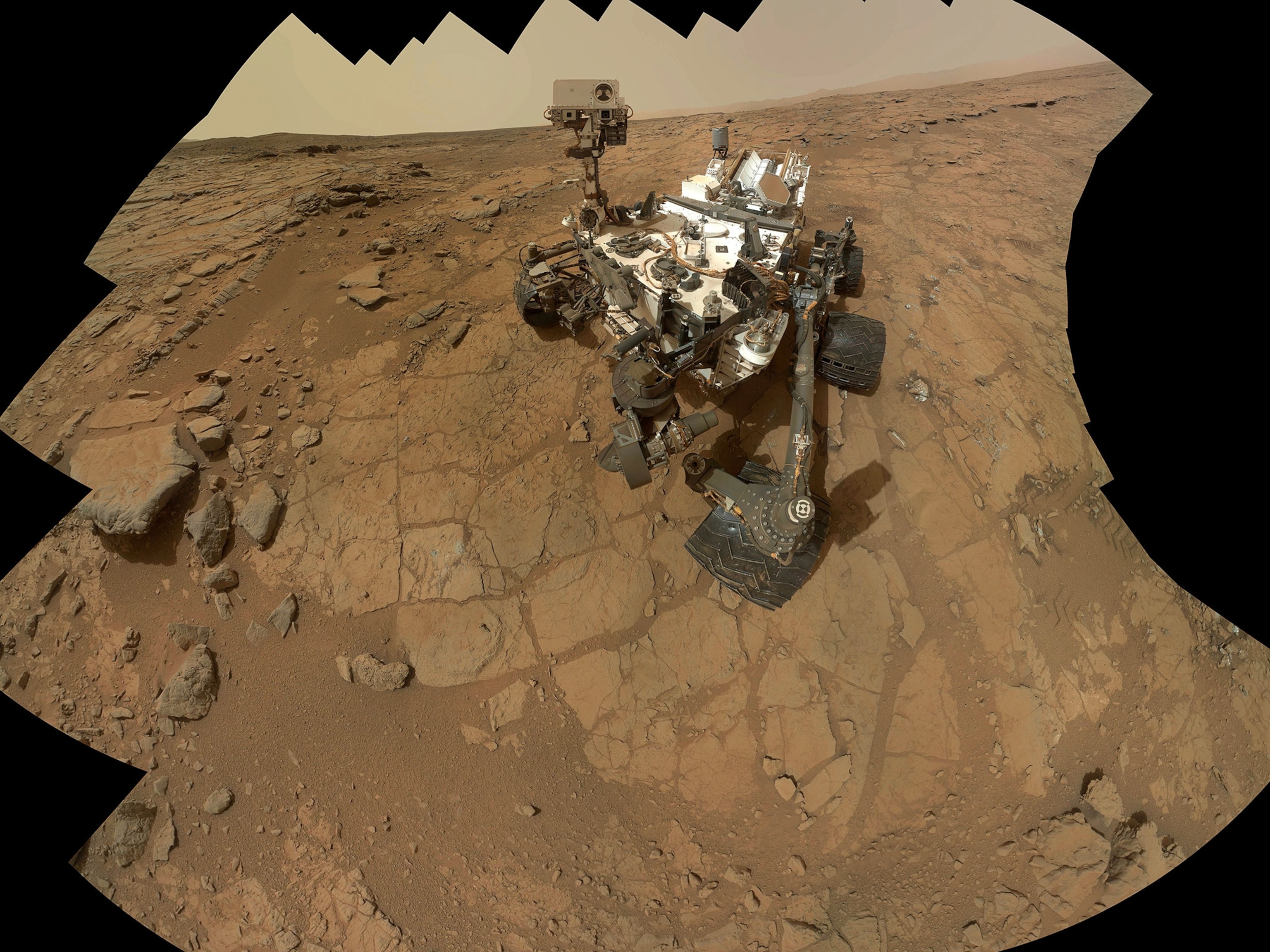

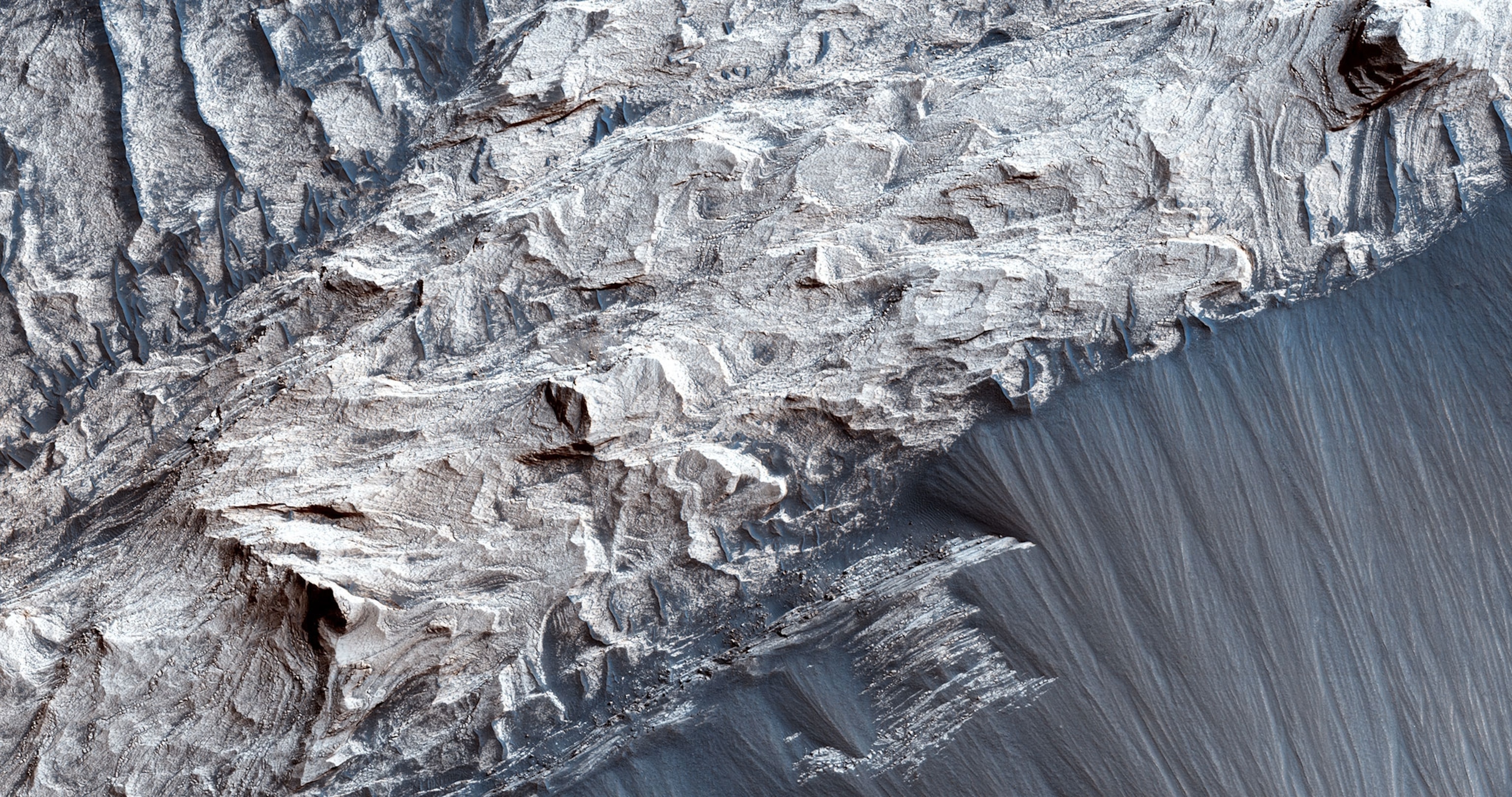

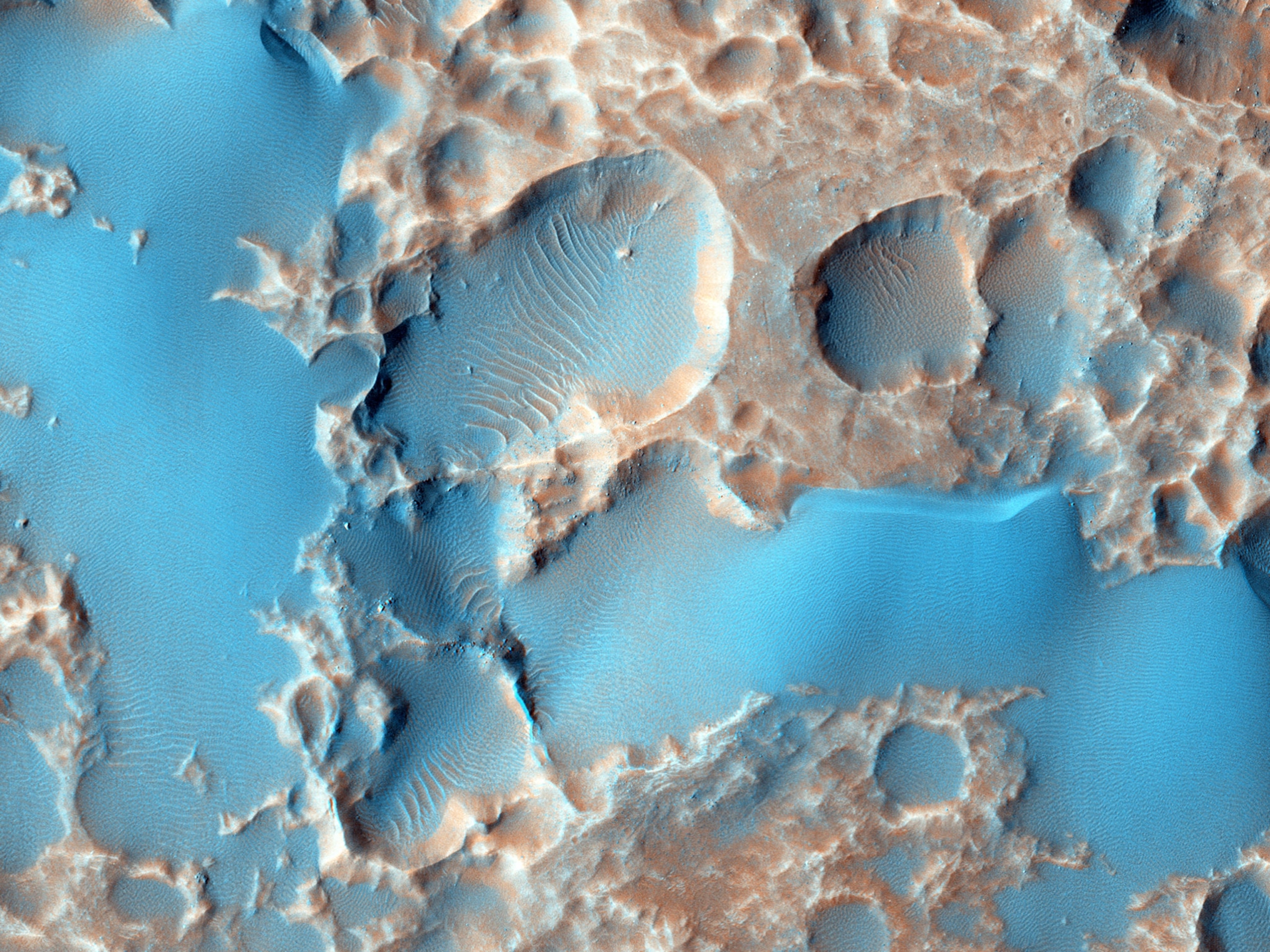

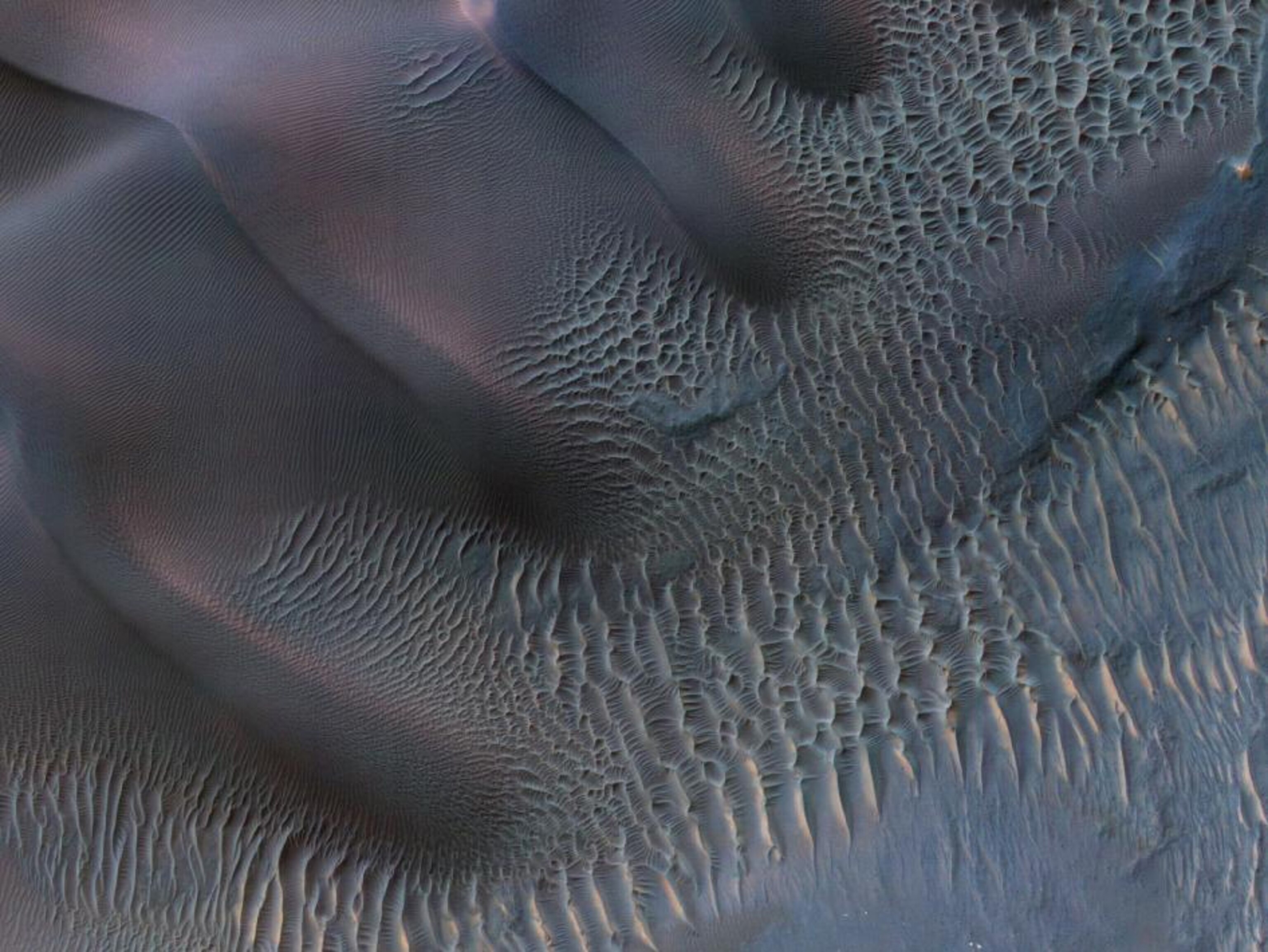

Even the shielding currently used on the International Space Station, which is low enough in Earth’s orbit to sit safely inside the magnetosphere, would not be enough to protect pioneering astronauts headed into deep space. A trip to Mars, for instance, would subject space travelers to doses of radiation comparable to getting a whole-body CT scan once every five or six days for the entirety of the trip.

One place on Earth may offer a unique opportunity to study the long-term effects of radiation exposure and perhaps find a way to better protect from it: Chernobyl.

“The secret to potential success for interstellar travel will come from looking at animals and plants and microbes on the Earth that have dealt with this kind of radiation in their evolutionary past, and their ability to either tolerate or completely avoid effects of this radiation,” says Timothy Mousseau, professor of biological sciences at the University of South Carolina.

A former power plant in what is today northern Ukraine, Chernobyl experienced a catastrophic nuclear reactor accident in April 1986, and it is still contaminated with same kind of gamma radiation that astronauts will encounter in deep space. Creatures big and small, from wolves to microbes, continue to live inside the thousand-square-mile Exclusion Zone. (See the new “tomb” built to house Chernobyl’s radioactive ruins.)

Mousseau has visited the site regularly since 2000, looking at hundreds of species to see how they react to the environment. Some, like the radiantly red firebug, mutate aesthetically, their normally symmetrical designs warped and fractured. Others, including certain species of birds and bacteria, have shown an increased tolerance and resistance to the radiation.

These differences may offer clues to help with human spaceflight. (Archaeologists are also studying Chernobyl—here’s why.)

“I think that within human genomes, there are secrets to biological mechanisms for resisting or tolerating the effects of radiation,” Mousseau says. “The trick is to figure out what those mechanisms are, and to maybe turn them on or enhance them in some way.”