Dear Mangalyaan: What India's Mars mission means to me

The record-breaking orbiter inspired one writer to keep dreaming of Mars—and showed the world what our shared future in space can look like.

Dear Mangalyaan,

It’s been five years since your historic launch off the east coast of India, and over four years since you settled into orbit around Mars. You’re living my dream. I must have been around your age now when my father first took me to the Nehru Planetarium in Mumbai, to show me how large my world truly was. We sat under the half-dome of the theater, and the lights faded out into a star field denser than any sky a city child ever sees. I could have fallen into that bowl of nightlight.

I felt the beginnings of a lifelong wanderlust for space. Mars would be my first stop—a hop-skip away, I thought. My father agreed. “It should be possible to land a person on Mars within our lifetime,” he said. “It could even be you.”

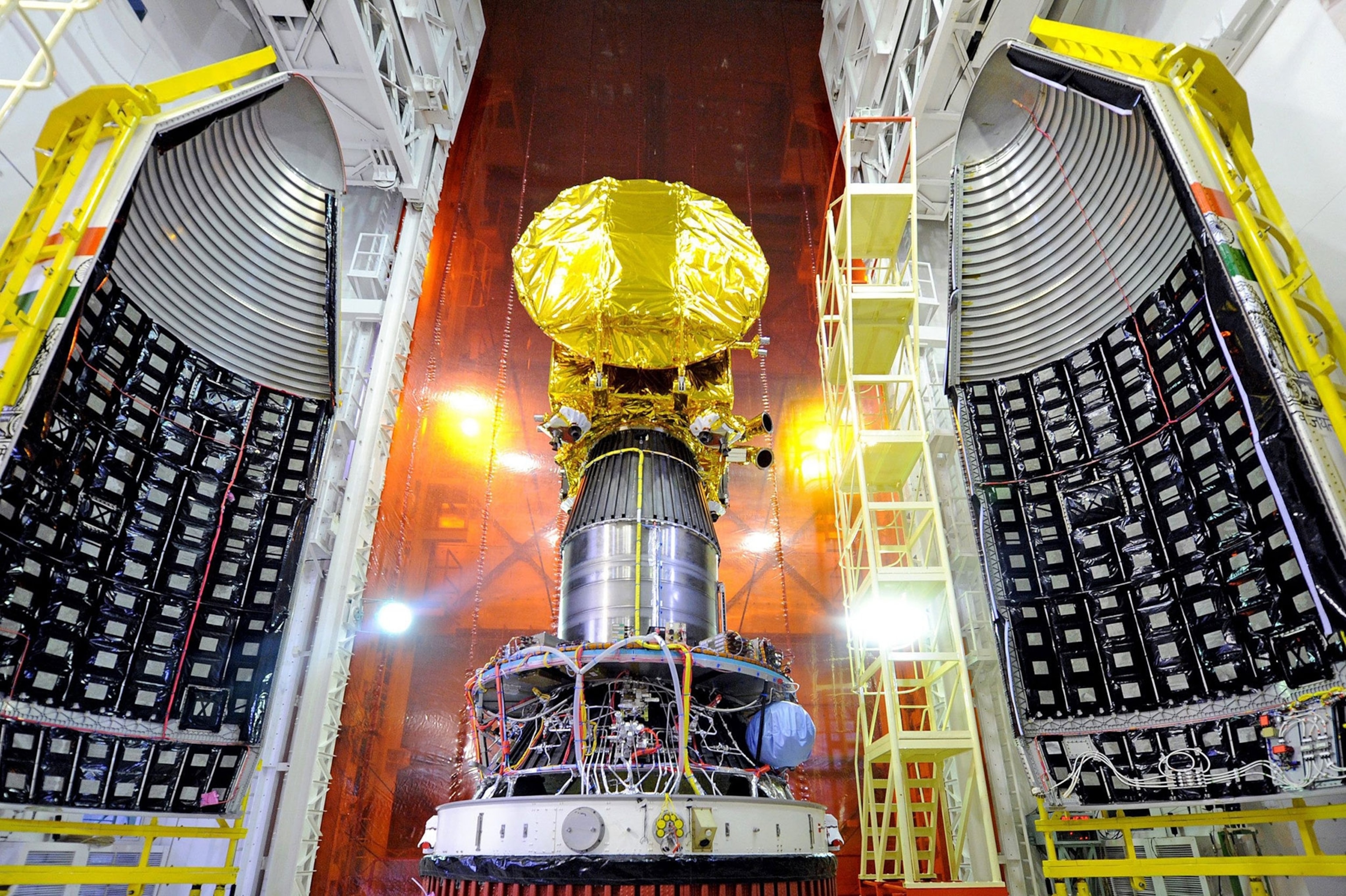

That was nearly 30 years ago. Today, you, Mangalyaan, represent what happens when people are bold enough to say something as audacious as, “It could even be you.” Indian scientists took less than two years to build you, and from your launch on November 5, 2013, to your capture in Mars orbit on September 24, 2014, you traveled more than 400 million miles.

Yours has been a remarkable voyage: nearly half of all attempted missions to Mars have failed, but with your success, India became the first country to put a spacecraft in orbit around another planet on its first try. What’s more, India accomplished this feat on a tiny budget: 4.5 billion rupees, or U.S. $73 million—less than the budgets of science fiction blockbusters like The Martian or Gravity.

And while your official objectives are scientific in nature, I cannot overlook your unofficial mission: to stoke young Indians’ interest in engineering and astronomy. I will leave it to others to explain how you’ve inspired their career paths. Perhaps they will note with pride that indigenous know-how built the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, the rocket that carried you into space. Perhaps they’ll cite the photos from the mission control room, when you sent word you’d made it—images of jubilant women staffers in saris, role models who resembled their mothers and grandmothers.

Fast Facts: Mangalyaan (Mars Orbiter Mission)

Agency: Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO)

Launch Date: November 5, 2013

Launch Vehicle: ISRO Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV)

Mars Orbital Insertion: September 23, 2014

Mass: 1,075 pounds (488 kilograms)

Power Source: 840-watt solar panel array

Their stories, and yours, motivate future generations of scientists who’ll spearhead the next Indian mission to Mars, or Venus, or back to the moon.

Engineering was never my expertise—I am a writer, a daydreamer. The only things I would pack for Mars are a box of paints, pens, and paper. But your presence allows me to imagine myself in your wake: not charting flight trajectories or studying the composition of Mars’s atmosphere, but writing poetry and sketching postcard vistas to send back home.

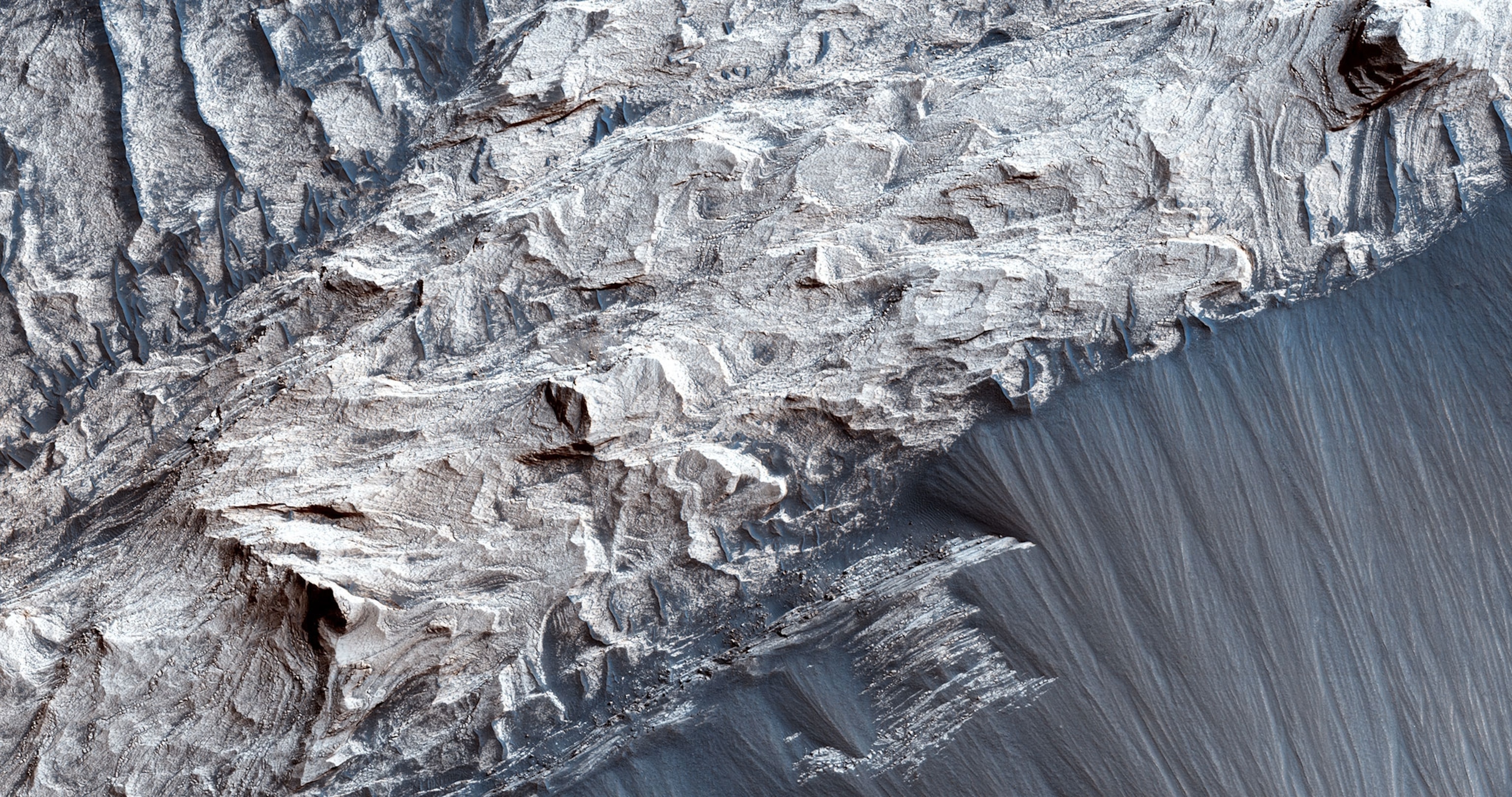

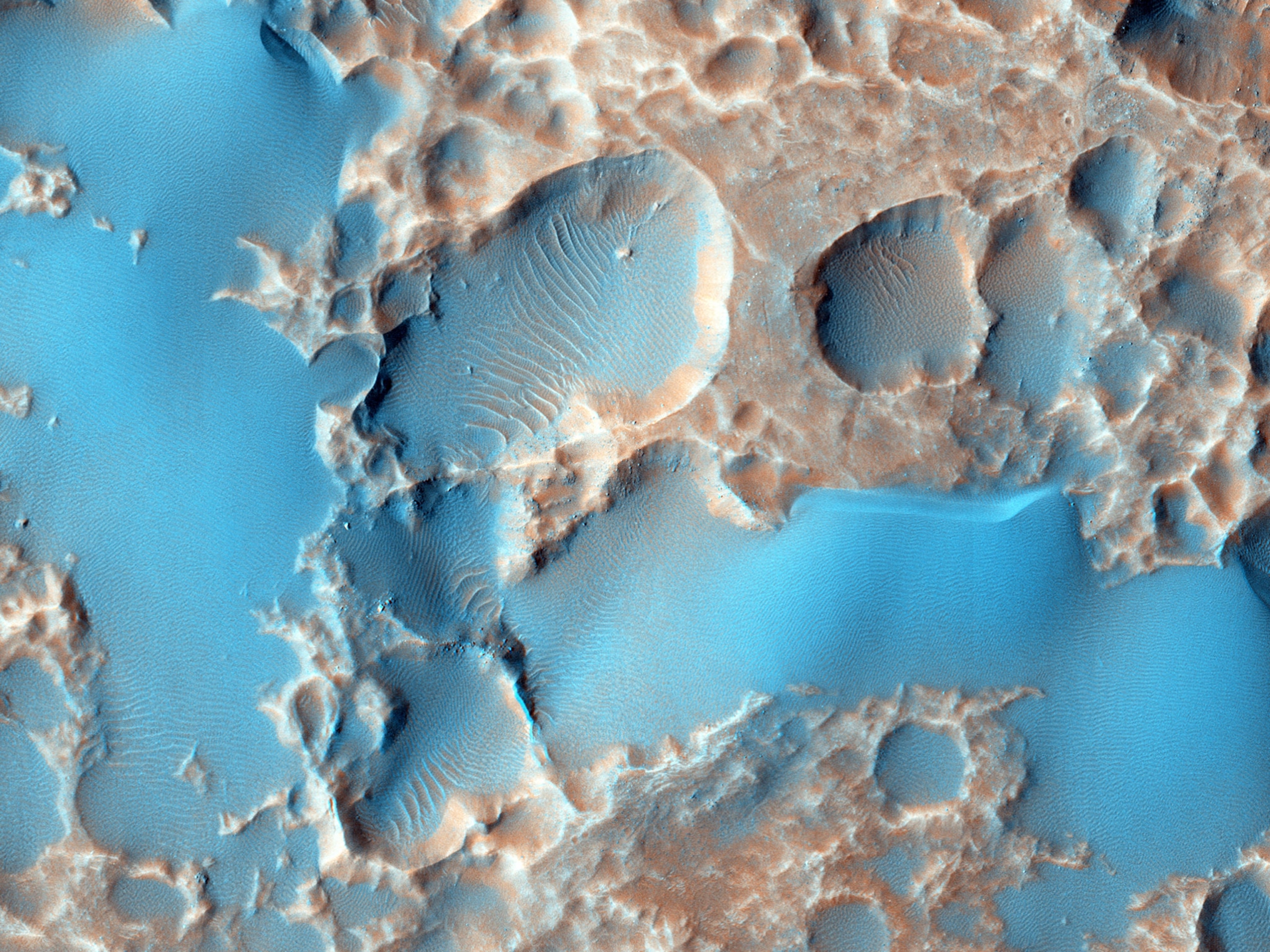

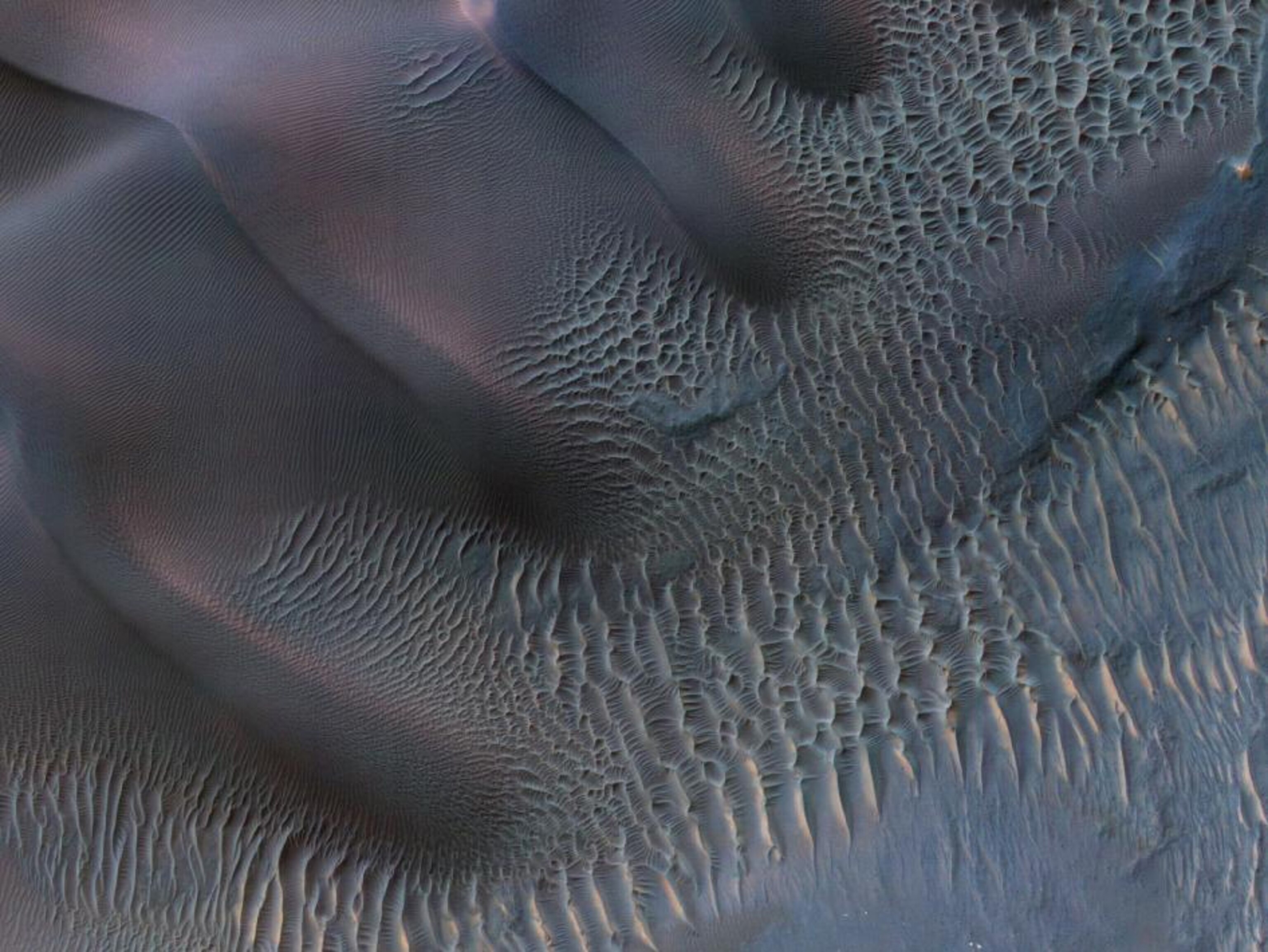

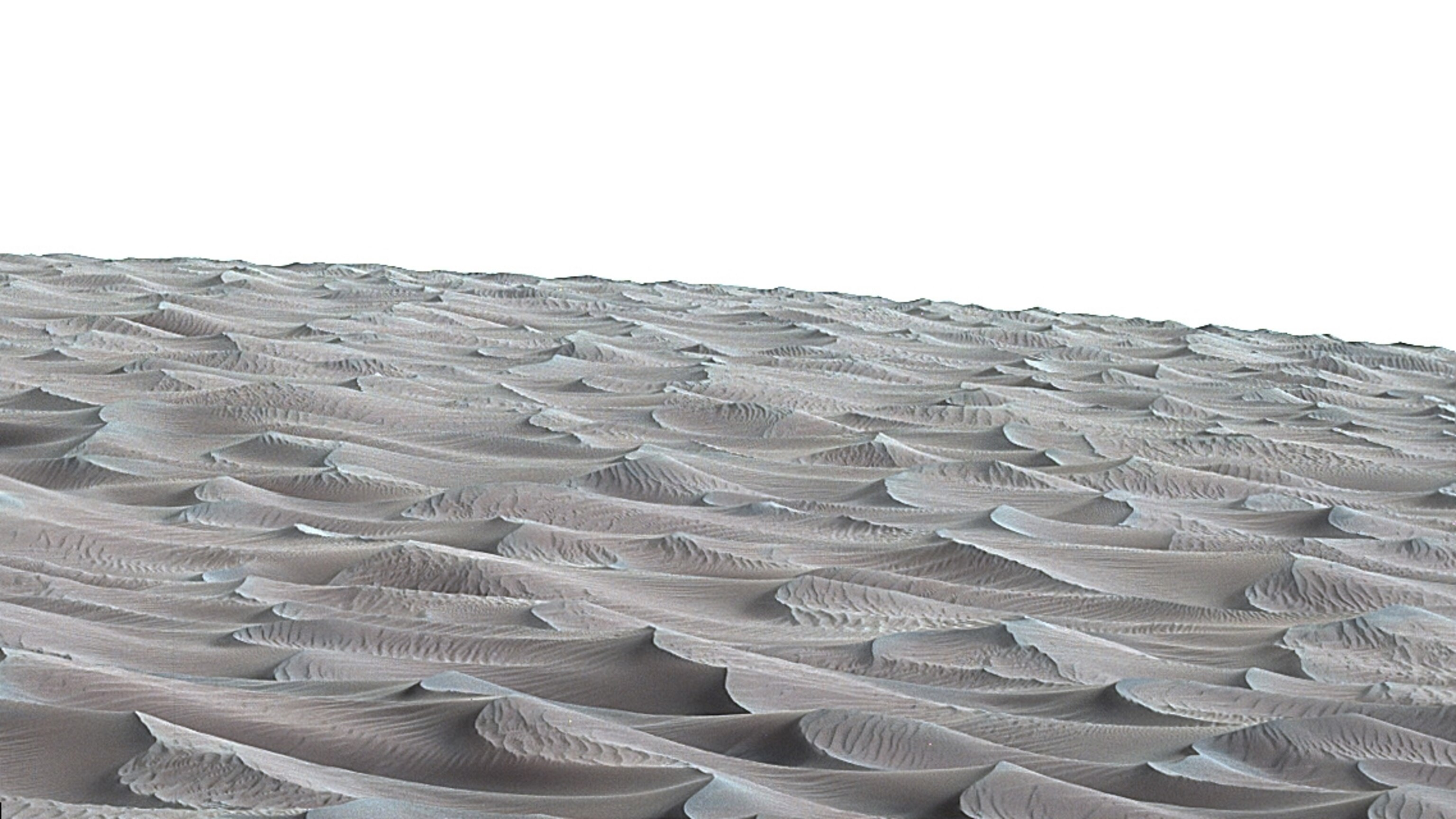

During your orbit’s closest approach, some 300 kilometers above the surface, we may drift over Olympus Mons, three times higher than the Himalayas’ Mount Everest, or Valles Marineris, a canyon longer than India itself that cuts up to four miles into the red planet’s surface. Then we’ll swoop out to the farthest point of your elliptical orbit, some 71,000 kilometers away. From this distance, you are in a unique position to capture Mars as a full globe—the planet resembles a cup of tea we share, a touch milky where clouds have gathered, resting upon a sugar-sprinkled black tablecloth.

I want to thank you for making space for me at the table. We both know how difficult it has been to get here.

The Indian Space Research Organization, the group that built you, was formed in 1969, the same year as the Apollo 11 moon landing. The timing is no coincidence. My father followed the news as it unfolded: the Cold War, the Space Race, one technological breakthrough after the other as the United States and the Soviet Union competed for military might. India, meanwhile, was a mere two decades post-Independence, rapidly modernizing and eager to establish a sense of self-reliance. Investing in space would let us build a telecommunications infrastructure, monitor our weather, survey our agriculture and natural resources, and conduct basic scientific research.

To this day, ISRO’s goal is to use space-based technology to foster national development, because even as we look to the stars for inspiration, our feet remain firmly planted on Earth. You are rightly feted, Mangalyaan—there’s even an image of you on our new 2,000-rupee note. But the current United Nations Human Development Indicators for India suggest that to earn this much money, roughly U.S. $27, more than 40 percent of India’s employed population would need to work for a week and a half. I follow your discoveries on the internet, a resource only 30 percent of the Indian population can access.

ISRO is presently one of just six government organizations around the world that can design, launch, and recover satellites and operate space probes—yet women in India represent a little over a quarter of the share of university graduates with degrees in the sciences, mathematics, engineering, and related fields. You symbolize where we come from and where we wish to go.

My father grew up keenly aware of educational and career-access disparities in India, which is why he moved our family soon after I was born. We went as far as he could afford: Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates. I hopped countries twice after that, and now, I live halfway around the world from my place of birth. You know what that feels like. Home is not a place for you: it’s the people who made you, the things you carry inside, and the people you write back to with missives about your latest experiences.

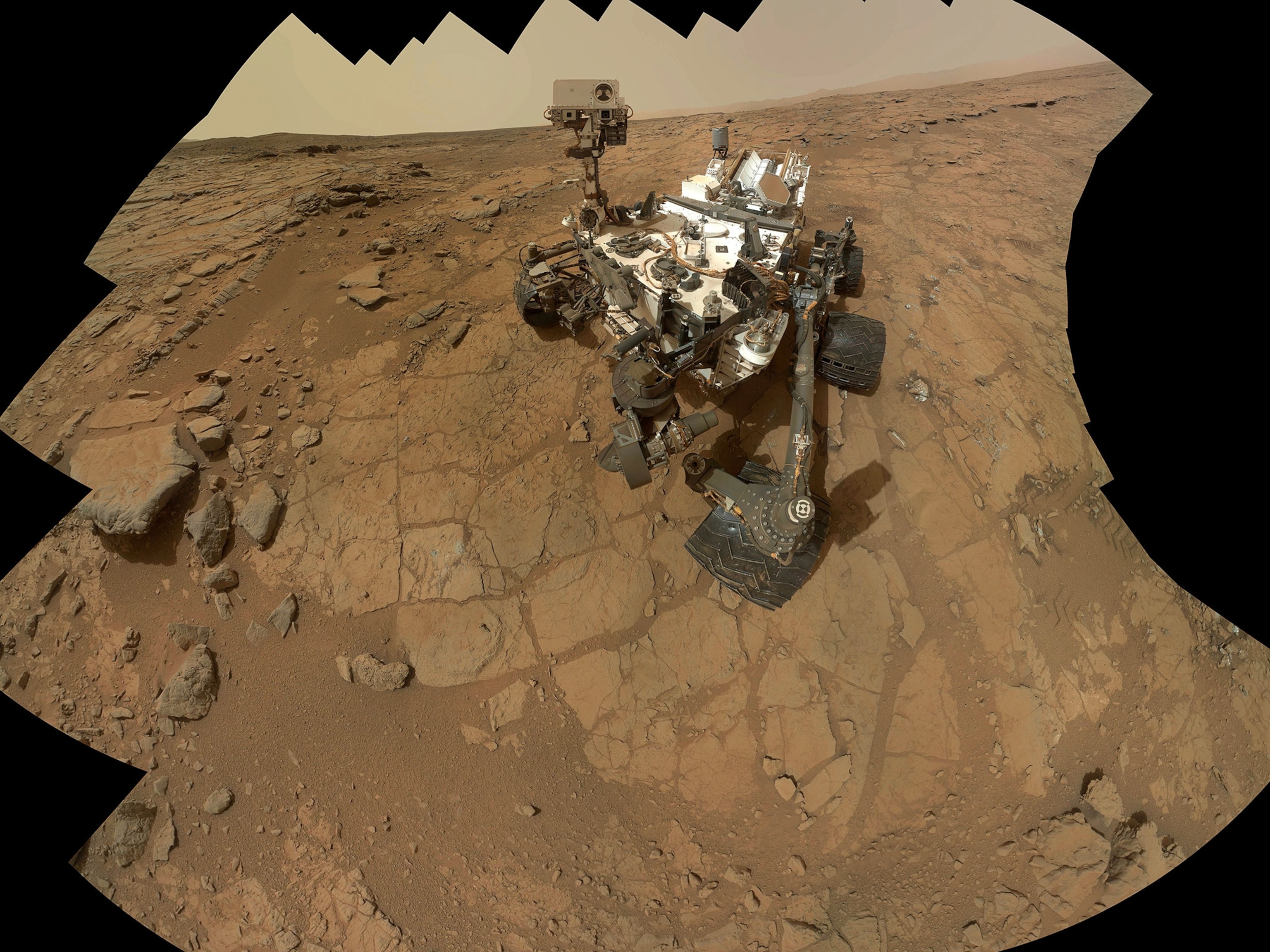

My father still lives in Dubai. Presently, I live in Panama. Just as you transmit data back home, we email each other the latest news about Mars. Did he watch the Curiosity landing livestream?, I write. Did I know more than 10,000 people applied to be a part of Mars One’s one-way trip to the red planet?, he writes. Elon Musk wants to set up a colony there, can you believe it?, I ask him. My father says he wishes he could go. I tell him we could never afford it.

As public interest in Mars continues to grow, I begin to fear a repeat of the old news from my father’s time of countries flexing their muscles to be the first to put a flag on Martian soil. Indians know the cost of colonization, as do most citizens of the global South. I am just one voice among 1.3 billion, but I use it to say that India orbits Mars today not because it wants a slice of that cold red pie, but because everyone deserves it. Space is our common heritage, no matter our place of birth or our means of access.

Mangalyaan, if you’ve shown me anything, it’s that there’s more than one way to get as far as you’d like to go, and the tenacity of the people who built you gives me a sense of hope. When I think back to my time at the Nehru Planetarium, no one told me I didn’t have a right to look up at the stars and see myself out there among them. On the contrary, I was encouraged to imagine freely—to feel that I could choose my own orbit.

You mean a lot to us, Mangalyaan. I say this now not as a member of the Indian diaspora, but as a very young girl in complete awe of the size of the known universe. We are all of us so small, and so lucky to be alive at a time when everything we discover makes our world seem larger, more complex, more profound than we knew before.

Thank you for showing us that we are capable of such discovery, that we are resourceful even with the odds stacked against us. Thank you for showing us that we belong.

Yours,

Geetha