On a sunny Saturday in June 2019, Brent Bauer, 56, was standing on top of his summer home on San Juan Island, off the coast of Seattle, power washing his roof. He had one last, hard-to-reach section left, and when he pulled the trigger on the power washer, it propelled him backward on the slick metal, causing him to lose his footing.

Bauer fell about 25 feet, which gave him just enough time for two thoughts before he hit the concrete: “This is it,” and “This is stupid.”

As he relays the incident to me in his kitchen back in February, his head is neatly shaven and his demeanor is one of calm control, edged with mild chagrin. Still, he shudders thinking back on that day, since so many things had to go perfectly for him to make it back alive. “I managed to turn in the air, which is miraculous, and I landed on my feet,” he says. “If I wouldn’t have done that, I would have died.”

Bauer calls his feet “the crumple zone,” likening them to the section of a car designed to absorb the impact of a crash. He landed first on his left heel, which shattered into 16 pieces, then on his right heel, which busted into as many fragments. Next, he bounced off his pelvis, which snapped into three pieces and splayed open 4.5 inches, tearing major blood vessels. He then landed on his wrist, which snapped and left the ulna bone protruding an inch and a half from his forearm. He recalls trying to stand, but his lower body collapsed beneath him.

When Bauer arrived via helicopter at Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center, he had severe internal injuries and multiple shattered bones, which would ultimately take a team of doctors 10 surgeries to try and piece back together. Over the next few weeks, the medical team had to put him in an induced coma for two days to curb the bleeding, save his organs, and stabilize his broken bones.

Today, his story of tragedy and treatment showcases the incredible innovation in delicate surgical techniques for repairing bone, and in managing the intense pain that accompanies these procedures. “I knew I was in mortal danger,” says Bauer, who describes his team of doctors with a litany of gushing superlatives. “The predominant thing I have felt since then is gratitude for being alive.” (Find out how scientists are unraveling the mysteries of pain in National Geographic.)

On a heel and a prayer

When not at work at the telecommunications company he owns, Bauer is a rock climber and a paraglider, and I can see in his eyes that these are not casual recreational pursuits. This is a man obsessed with pushing limits. In 1984, he was working on a salmon fishing boat in the Bering Sea when a wave swamped the vessel at night. The crew abandoned ship and floated in their survival suits until they were rescued by another fishing boat two hours later. While on safari in Zimbabwe in 2005, Bauer was on a tree branch trying to photograph a crocodile when he fell and landed on his back, causing bruises that bordered on necrosis and compression fractures to three vertebrae.

“Because I’ve been lucky so many times in my life, I just had this false impression that the really bad stuff doesn’t happen to me,” he says.

Prior experience with personal injury and the strength gained from his recreational pursuits served him well on that fateful day in June. Before panic could set in, Bauer looked up and saw that his phone had bounced out of his pocket during the fall and lay about 20 feet away. He used his knee and one good hand to drag his body over to the phone and tried calling his neighbor, who didn’t pick up.

His next call was to 9-1-1 to summon the island’s volunteer medics, and then Bauer’s memories become scarce. While laid out in a helicopter, he recalls seeing a dim blue light in the distance. When the light beckoned him, he mentally moved toward it, convinced he had died. Bauer lost consciousness by the time the chopper made it to the hospital across Puget Sound. He would not wake up for two days.

It’s a stroke of luck that Bauer fell within easy distance of Harborview Medical Center. The facility is a Level One trauma center, the highest of the five levels of care evaluated by the American College of Surgeons. It’s also home to leading surgeons skilled in the cutting-edge techniques needed to reassemble his mangled insides.

“It just so happens that the best foot and heel doctor in the U.S.—and probably the world—works at Harborview, and he was my doctor,” Bauer says. “I’m so grateful for that.”

Foot surgeon Stephen Benirschke shows up to our interview wearing a crisp white shirt and a tightly knotted tie topped with a fleece vest to keep it Seattle casual. He was still relatively new to Harborview in 1985 when his advisor tasked him with “figuring out how to fix feet.” The medical literature back then had nothing on fractures of the calcaneus, or heel bone, even though those are the most common fractures of the foot. In most cases, doctors just didn’t operate.

Over time, Benirschke developed a method that has become the gold standard. He attaches a pin to each shard of bone, and then uses those pins to move each piece back into place, like putting together a broken egg shell. Once they’re arranged, he uses a sheet of metal mesh to wrap around the heel and stabilize it for the healing process. He says the key to a calcaneus repair is remembering that its job is to hold up everything above it; the entire human body stands on its support. “It’s a very cool bone,” Benirschke says.

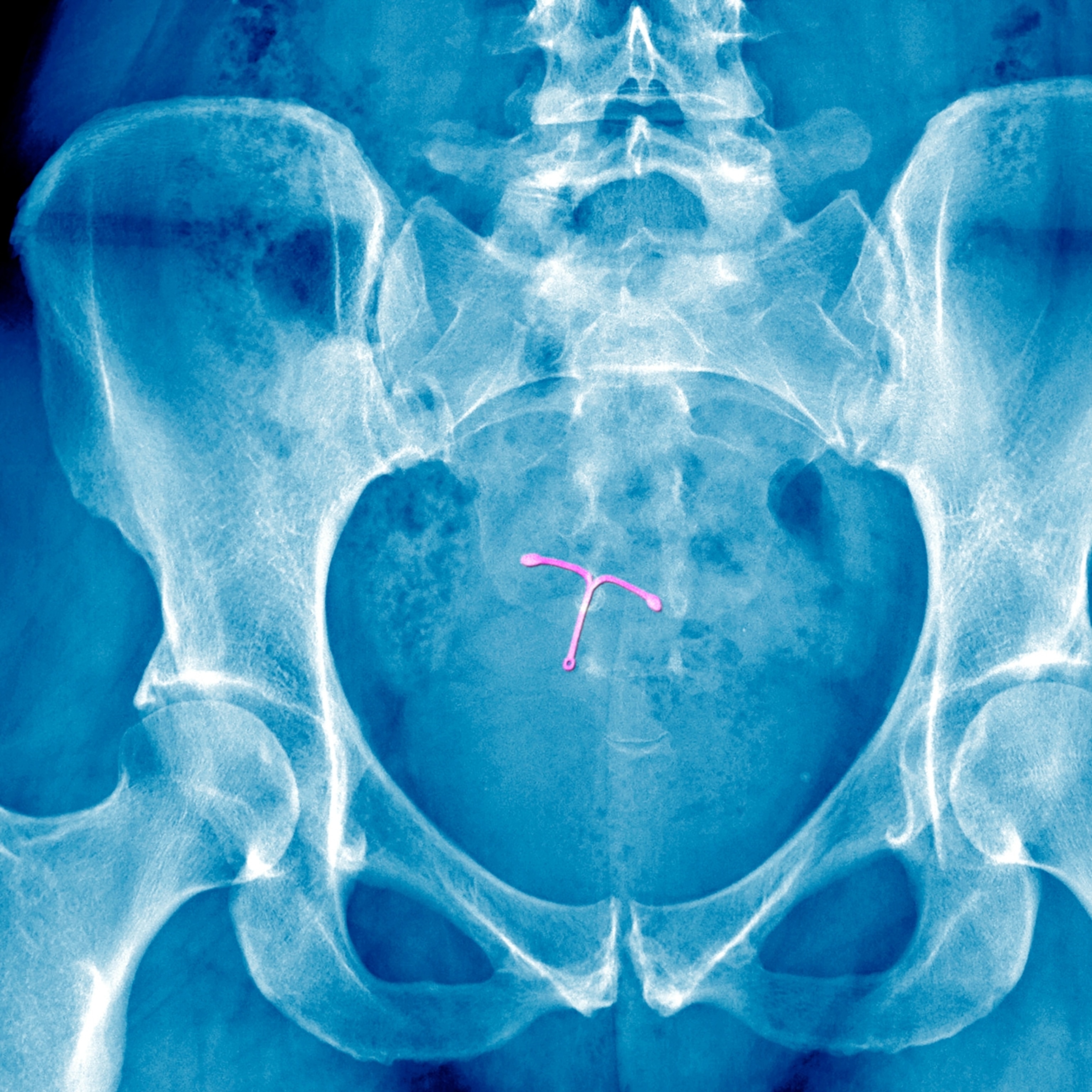

This innovative heel surgery helped Bauer clear one hurdle to recovery, but arguably tougher ones remained. A different surgeon had to stabilize Bauer’s broken pelvis with an external frame fitted with six-inch pins drilled into his hip bones. Eight weeks later, his bones had healed enough to remove those pins.

Sporting a white doctor’s coat and an affable smile, Reza Firoozabadi, the in-house pelvis expert at Harborview, uses a full-size skeleton model to show me where the pins were placed. Removing them is not technically an operation, he says; it’s just a matter of unscrewing the pins from the pelvis, which can be turned by hand on the external frame. It’s a simple procedure, if a painful one. Historically, the process happens in an operating room, with the patient under anesthesia.

For Bauer, though, Firoozabadi offered two options. He could go into the operating room and have anesthesia and a breathing tube yet again. Or he could participate in a research study that involved removing the pins as an outpatient procedure with virtual reality used in place of pain medication. Bauer jumped on the opportunity to avoid another intubation.

OR versus VR

Pain is a tricky thing to manage. It’s a subjective experience, and there are psychological factors that can undermine the effectiveness of pain medications. Warned that an imminent procedure will be painful, a patient may feel a lot of things: anxiety, depression, anticipation, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from previous experiences. So, VR is not just about distracting the patient; it’s actually undoing these negative psychological effects.

“These all well up,” says Hunter Hoffman, a research scientist in the Human Photonics Laboratory at the University of Washington. “And they are all knocked out by VR.” (Here’s how VR is also helping football players, first responders, and climate scientists.)

Hoffman initially designed the VR program to treat burn patients during their agonizing wound care; that’s why he made it a cold virtual environment he calls SnowWorld. To undergo the removal of the first pin, Bauer was wired up to a VR headset and dropped into an icy canyon. There, he was surrounded by penguins and mammoths that he was supposed to hit with virtual snowballs, using a computer mouse in his right hand. Shooting snowballs lowers pain in part due to the distraction of interactivity, but also due to the willingness of a patient to suspend disbelief, Hoffman says. People are motivated to allow themselves to get into the game because the reward is less pain.

The other advantage of VR is just how targeted it is. Drugs don’t turn on or off instantaneously, but when a patient takes off the VR headset, the effects stop.

As the first screw was removed, Bauer says, the VR experience probably cut his pain in half. For the second screw, Firoozabadi did the same procedure without the VR (with Bauer’s permission) as a control in the scientific study. Bauer says the pain was excruciating, and that he had tears streaming down his face. He tells me he went into it thinking he could handle anything for three or four minutes, but this procedure proved him wrong.

Ever the competitor, Bauer did offer Hoffman some feedback to use with the VR therapy going forward: Keep score. If the game is more competitive, it’s easier to get sucked in, Bauer says. Firoozabadi, too, had some ideas for Hoffman. Rather than a snowscape, he suggested, destinations tailored to patients’ individual tastes could be built for future iterations, to make the experience even more immersive.

Tools of therapy

For Bauer, visions of real-life escapes drive him to keep getting stronger as winter turns to spring. He has taken an early retirement and is now focused on building up a life full of joy and adventure, though perhaps without so much unnecessary risk. He had known his girlfriend, Sarah Bartolac, for only six weeks when he fell off the roof, and she’s still here, attending his physical therapy appointments, managing his in-home care, and smirking lovingly as she listens to him describe his plans to go paragliding the following week. “He loves adrenaline,” she tells me. Bauer’s response is characteristically self-assured: “Just four good steps,” he repeats, almost like a mantra. That’s all he needs to get airborne.

His physical therapy and fitness routine takes up about four hours a day. And that’s on top of the sessions he does at the University of Washington’s Husky Stadium, which includes a technique pioneered in Japan called blood flow restriction therapy that encourages muscle growth through careful control of oxygen delivered by blood.

When I visit his therapy session in March, Bauer is eager to show off the anti-gravity treadmill, or as he calls it, “the wedgie machine,” at Husky Stadium. To use it, he puts on a pair of shorts that resembles the skirt on a sea kayak. He steps onto the treadmill and zips his shorts onto a bag that surrounds the machine, which he then inflates. He can adjust the air pressure up or down to determine how much of his body weight is supported by the device.

When he began his recovery, just three months after his accident, he was doing self-directed therapy on this treadmill. He would roll his wheelchair over and then haul himself up with his arms. He was allowed to walk with just 35 percent of his body weight. Today, he’s feeling especially strong and wants to see what he can do. He starts decreasing the inflation pressure to increase the amount of his weight held up by his own legs, now nearing 85 percent. As he is describing to me how the treadmill works, he gets an idea.

“In fact, let me try something,” he says. He begins to increase the speed of the treadmill. Slowly at first, and then more eagerly. His steps transform from the intentional rhythm of a walk, albeit with a bit of a lilt, to the faster pace of a full-on run. The sound that escapes this strong and serious man as he realizes he is running, for the first time since his accident nearly nine months ago, is giddy laughter.

“Look what I can do!” he says gleefully. “Sarah, I’m running!” He continues his childlike pronouncements for a while before going quiet. He focuses on his form and tries to savor the sensation of running “so I remember what that feels like,” he says.

Despite this moment of hope, I can’t say I’m surprised when I get another email a few months later, this time with photos from a subsequent surgery. “Turns out that I overdid it with my activities and broke most of the screws that were in my left foot,” Bauer writes. It has now been more than a year since his fall, but without missing a beat, the note switches to his usual tone of relentless optimism: “I’m doing great now and healing fast. In a couple weeks I can start putting full weight on it, and I believe I will eventually get back to 100%.”