First pig-to-human lung transplant announced by Chinese scientists

The xenotransplantation comes on the heels of recent transplants of pig hearts and kidneys into medical patients.

For the first time ever documented, a pig lung was transplanted into a human, scientists in China announced on Monday in a study published in Nature Medicine. The transfer, which took place in May, 2024 in Guangzhou, was short-lived—the patient was brain-dead and the immune response was only monitored for nine days. Scientists told National Geographic they stopped the experiment once “our main scientific goals were achieved”—assessing the patient for uncontrolled infection and organ rejection—and also at the family’s request.

The study marks another critical milestone for xenotransplanation, or the practice of exchanging organs between species, and comes on the heels of recent transplants of pig kidneys and hearts into human patients.

The 39-year-old patient didn’t immediately and intensely reject the lung, which was from a gene-edited pig, the study authors noted, though the person did exhibit an immune response and some organ damage. The scientists added that “substantial challenges” remain before lung xenotransplantation can be safely performed in a medical setting, including how to best manage that immune response.

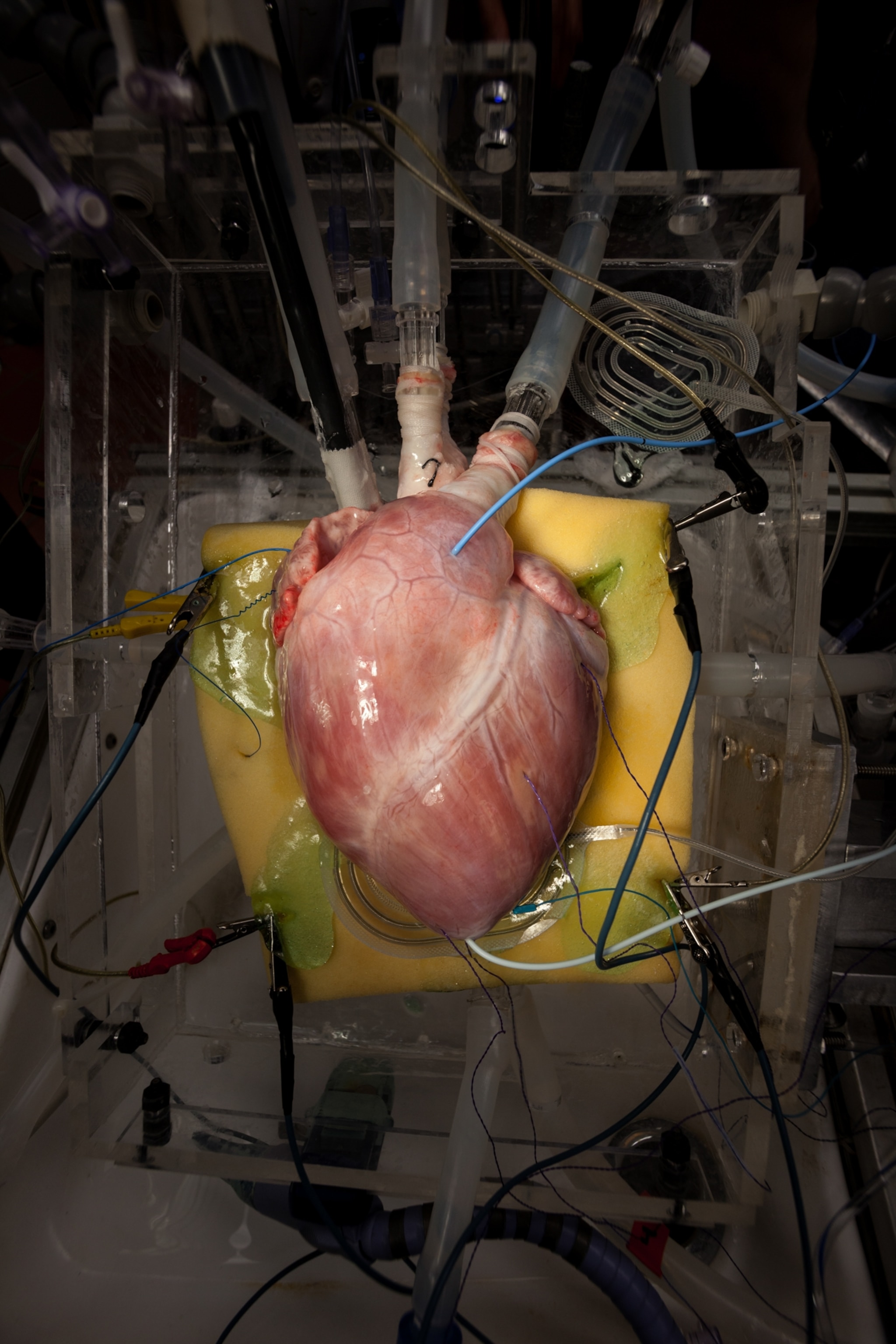

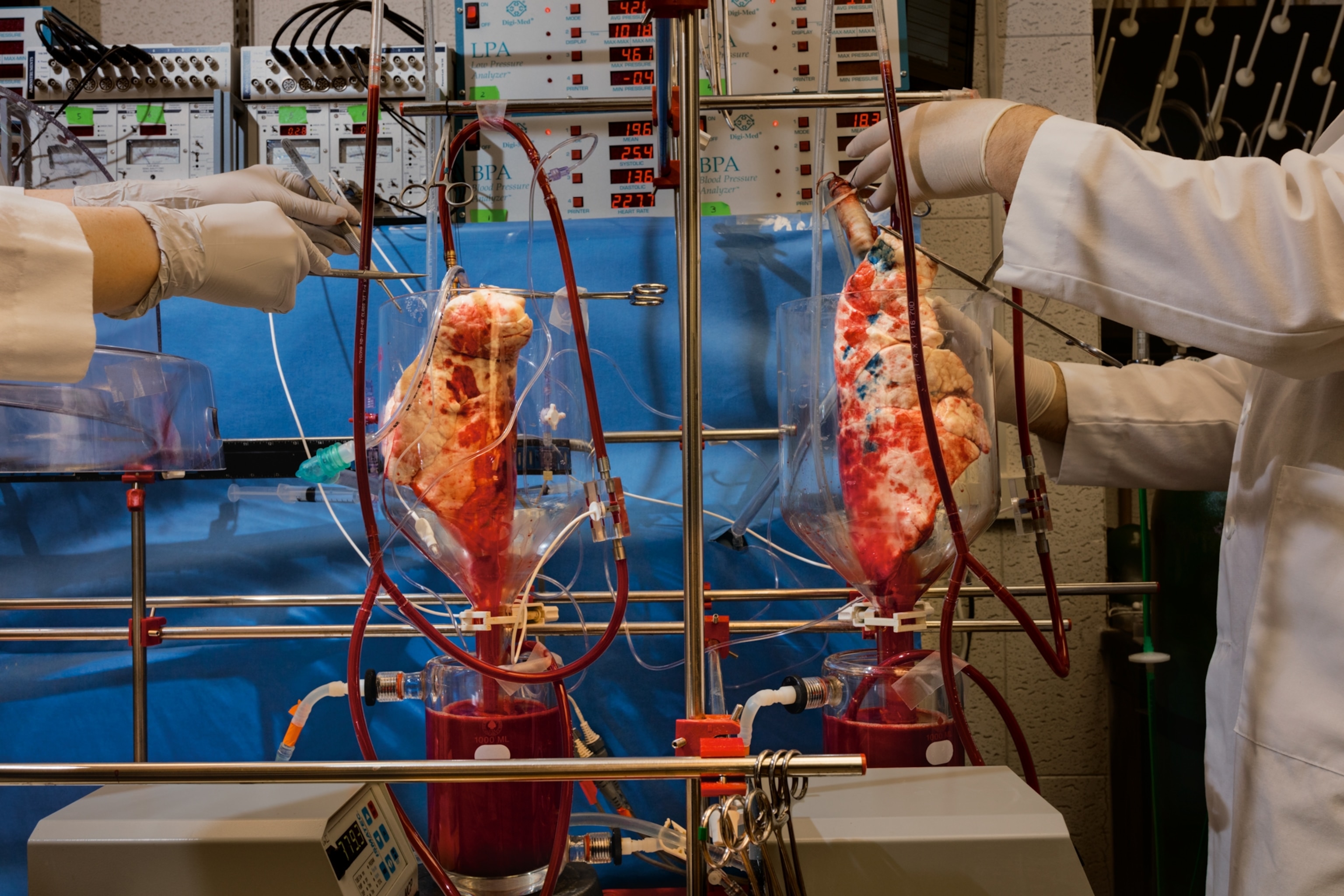

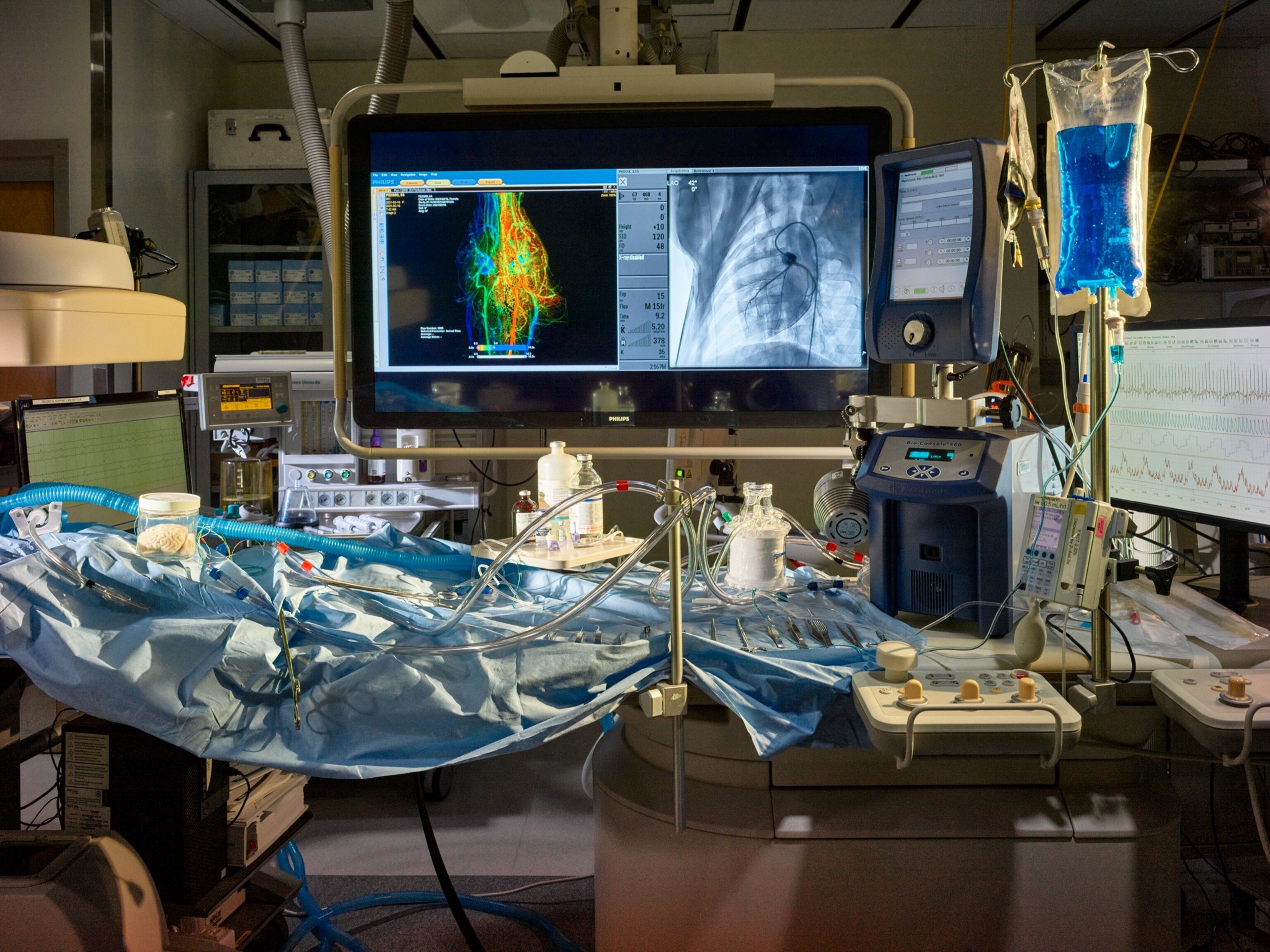

(Inside the secret lab where pig organs are being grown for humans)

“[W]e must remain cautious: current evidence does not support clinical use in living patients,” Jianxing He, lead author on the paper, told National Geographic. More studies —including longer trials on brain-dead patients—must be done to reduce injury to the lung “before any clinical consideration.”

Outside experts say that the study, while not especially surprising in its results, is a crucial step for pig-to-human transplants. “If we establish safety and efficacy … this could be a paradigm shift long-term,” says Ankit Bharat, chief of thoracic surgery at Northwestern Medicine.

Each year, surgeons perform thousands of lung transplants in the U.S. but wait times can be dire. But demand is growing, and depending on priority, recipients might wait months or years for a limited number of healthy and compatible human lungs. And receiving an organ from a human donor “is like buying a used car,” Bharat says, noting that “you don’t know what you’re getting” because donor health and the condition of the organ can vary widely. A steady stream of healthy animal organs could, at least hypothetically, standardize the quality of transplants, he added.

(The ability to reverse damage to your lungs is tantalizingly close)

Hospitals and biotech firms across the country are already running clinical trials transplanting other organs from genetically modified pigs into humans, including hearts, livers and kidneys. Scientists transplanted the first modified pig kidney into a living human patient last year, but that patient, Rick Slayman, died two months later. Another patient, Towana Looney, rejected a pig kidney after about four months. David Bennett, the first person to receive a gene-edited pig heart, died two months later; Lawrence Faucette, who received the second gene-edited pig heart transplant, lived for six weeks after the surgery. Scientists also transplanted a gene-edited pig liver into a brain-dead human in China last year, which appeared to function in the body for 10 days.

More than 100,000 people in the United States are currently waiting for organ donations, a few thousand of which are for lungs. Experts estimate that only about a fifth of donor lungs are actually viable for recipients. “Lung transplant is the worst in terms of five-year survival, and has pretty poor outcomes in general,” says Brendan Keating, an associate professor in the surgery department at NYU Langone. NYU Langone conducted two pig kidney transplants into living humans last year and has performed 6 pig kidney transplants into brain dead patients since 2021.

But experts say lungs can be far more complicated to transplant than other organs, because they exchange gas with the environment, which exposes them to pollutants, while also performing the crucial function of filtering blood. Their size also makes them more vulnerable to rejection compared to other organs, Bharat says.

“It’s a positive study, it’s shown it’s possible to do it,” Keating says. But “there’s still a fair amount of biology to be figured out” before lungs can be transplanted from pigs into patients widely, he added, noting that there need to be more trials examining transplant response in brain-dead recipients whose families or guardians have consented, a standard step in xenostransplantation research.

The study’s authors also acknowledged several outside factors may have influenced the results: The pig had been genetically modified to reduce the risk of rejection, and the recipient was given a host of antibodies to suppress immune response. The recipient also already had another lung, which could have influenced immune response and the donor lung’s function.

The observation period in the Guangzhou study also wasn’t long enough to determine whether the body might reject the organ later, Bharat says. “A short-term success, even if you have a lung that survives a day or two, does not necessarily translate into shorter or long-term success,” he said. Nevertheless, the transfer will likely further scientific understanding of pig lung xenotransplantation, Bharat added, which has mostly been tested on non-human primates.

Despite the potential benefits to human recipients, raising animals in labs purely for their organs, and experimenting on brain-dead patients who can’t vocalize consent, present complicated bioethical concerns, says Insoo Hyun, an affiliate at the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics. “It’s a call that the institution makes, and the ethical reviewers have to make,” he said.

And even if it’s proven to be safe and viable for humans, xenotransplantation could eventually lead to a “two-tiered system” in which some patients get animal organs while others get human ones. And if it turns out there are differences in quality between the types of organs, he noted, “if [there is a] second-best option, who gets the second-best one?”