This pig could save your life

For decades, scientists and surgeons around the world have been trying to solve the organ donor crisis. The answer could be rolling in the mud.

THE ENTRY REQUIREMENTS should have come with an instruction booklet: Sign in at the security hut. Shoes off at the door. Over to the locker room for a hot shower. Into a long protective surgical smock and knee-high rubber waders, and finally, a pair of safety goggles, which—in the clammy heat of the laboratory complex—quickly began to fog.

“Sorry for the trouble,” smiled my tour guide, Bjoern Petersen, waving me forward. “We just have to be exceptionally careful about pathogens. You’ll get used to it, I promise.”

A couple of hours earlier, I’d awoken in a hotel in a Midwestern city I’ve been asked not to name. Now, with the sun curdling above the surrounding pasture and a gauze of mist in the air, I found myself following Petersen, a German-born scientist, through the corridors of a highly secret research facility and across a muddy courtyard crosshatched with boot prints. “When we bought the place,” he said, “the owners were using it as a livestock research facility.” He indicated an adjacent barn. “The cattle were here, and the horses in the field up there. We’ve kept the same basic layout, though obviously our purpose is very different.”

He said something else as we entered the barn, but I didn’t catch it—his voice had been drowned out by a raucous chorus of expectant grunts and the clatter of trotters on cement. A dozen-odd pigs surged forward to the edges of the individual enclosures, clanging their snouts against the metal gates. “I want you to meet someone,” Petersen said, blinking into the harsh overhead light. He stopped near the pen of an animal whose name card identified her as Margarita. She curled her body against Petersen’s hand, in the manner of an oversize house cat. “Margarita was one of our first,” Petersen said proudly, leaning down to stroke the protuberant black hairs between the pig’s ears. “Most of these animals you’re looking at were created from the same cells. But there’s something special about the first, don’t you think?”

Petersen, who serves as the site head at the farm, is a specialist in livestock cloning and xenotransplantation—an exceedingly advanced scientific technique in which animal matter is transferred into human patients. (The name derives from the Greek for “strange” or “foreign.”) In 2023, after nearly a quarter century working at government research institutions in Europe, Petersen uprooted his family and moved to the Midwest to take a job with eGenesis—a biotech firm backed by a group of venture capital firm investors—then in the early phases of a remarkable plan to develop genetically modified pig kidneys for transplantation into humans. Powered by advances in gene editing and immunosuppressive medicine, eGenesis had quickly demonstrated that its organs could survive for long periods in the bodies of primate test subjects, filtering blood and producing urine as ably as an “allotransplanted,” or same-species, kidney.

Now, two years later, Petersen and eGenesis stand at the forefront of a major revolution in the science of organ transplantation—a revolution that will have implications for the global human donor shortage and the thousands of sick patients who wait every year for a new kidney. Already, the results have been astonishing: a progression from trial transplants on primates to transplant surgery on brain-dead human recipients—and finally, last March, in a development that made global headlines, to a transplant into a living human recipient.

Food and Drug Administration officials have since given eGenesis the green light to conduct a three-patient clinical trial, a move that added to the surging interest the company has generated since last year’s historic xenotransplant. Provided it stays on track and its trials prove successful, eGenesis’s CEO Mike Curtis says, the company is making plans to grow its production capacity, and he thinks the science could become widely available to the public before the decade is out. “In the long term,” he added, “I’d argue we’re looking at a scenario where cross-species transplants fully supplant allotransplants. Where we don’t need human donors anymore.”

Reaching that point will require further refinement of the technology and will demand more pigs like Margarita and scientists like Petersen. But more than anything, it will require trust on the part of those who go under the knife, who put their lives in the hands of this cutting-edge science and the doctors and hospitals championing it. And last year’s successful xenotransplant—a four-hour procedure completed at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital that demanded untested faith, a hefty dose of desperation, and an unmeasurable amount of luck—was perhaps the most significant step forward into this new future.

(The doctor who believes pig hearts could end our organ shortage.)

And it all started on a farm in the Midwest, where, on a cold March morning, a van idled in the dawn air. Its door slid open, a one-year-old pig was trundled inside, and the vehicle rolled down the drive, carrying what amounted to years of medical research, hope, and investment snorting in the back.

For the next 18 hours, as the van traveled eastward along I-90, a million scenarios raced through Curtis’s mind. “You’re sitting there, thinking, What if the van gets hit by a car?”

Or what if Rick Slayman changes his mind?

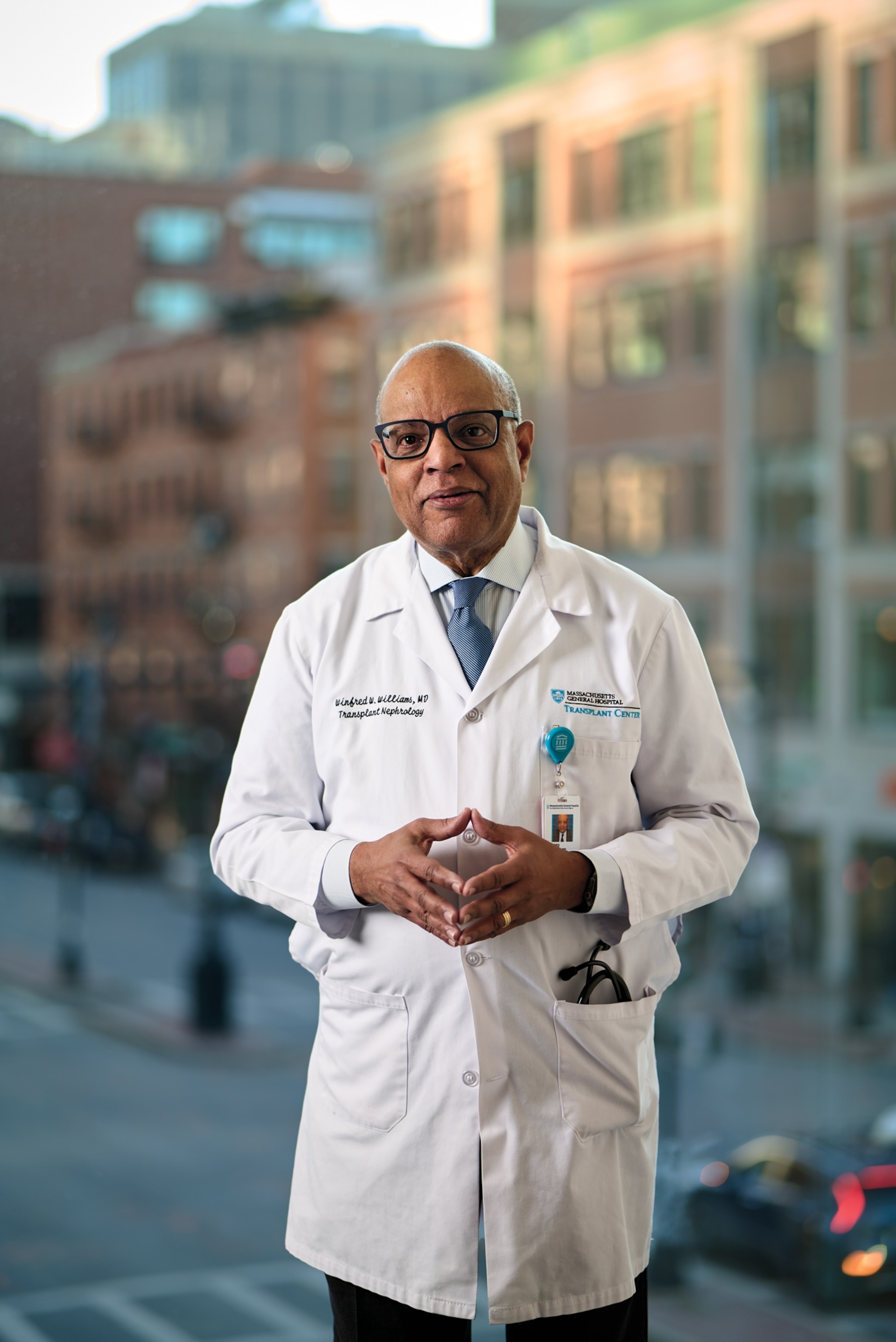

THE ROOM WAS SILENT. All other options had been depleted, and time was slipping away. Sitting at his desk in his office at Massachusetts General Hospital, looking across the room at a man who had become his friend as much as his patient, nephrologist Winfred Williams asked his long-shot question and waited for the response.

“Are you familiar with the term ‘xenotransplantation’?”

Rick Slayman, who was running out of vasculature access for dialysis, shook his head. Williams wasn’t surprised. At this point, in 2023, xenotransplantation was still a subject relegated to scientific journals and the occasional short news item on skin grafts or corneal transplants. So he did his best to explain that rapid advances in gene editing were offering hope that doctors might soon be able to place a pig kidney inside a human without the risk of acute and immediate rejection. Williams had been talking a lot with the folks at a biotech company across the Charles River called eGenesis. He’d learned that it had recently been granted approval from the FDA for an “expanded access” trial—a special allowance to treat patients who have no alternative treatments available to them.

Williams did not need to tell Slayman that he qualified. A supervisor with the Massachusetts Department of Transportation and a cheery man with the habit of charming nearly everyone he met, Slayman had struggled all his life with hypertension and diabetes, frequently twinned conditions that had given way to end-stage renal failure: significant destruction to his kidneys and declining function in both. Slayman had been prescribed a course of dialysis, but as Williams later recalled, the treatment had quickly become intensely time-consuming for his medical team and excruciatingly painful for Slayman. “For dialysis to work properly,” Williams told me, “you need to have reliable vascular access.” Traditionally, that access is secured via an arteriovenous fistula, a surgical connection between an artery and a vein and perforated by a pair of needles. One needle removes the patient’s blood; the other channels back a “cleaned” version. “The problem in Mr. Slayman’s case,” Williams said, “is that he was experiencing significant blood clotting, and it made it difficult to get a continuous flow going during dialysis. In a given year, he was undergoing multiple declotting sessions at a hospital. Back and forth, back and forth.”

It was a hard way for anyone to live, let alone someone as naturally energetic as Slayman. And the long-term prognosis was grim, Williams knew. Effective dialysis does not reverse damage to the kidneys. It simply makes it possible for a patient to continue living. In the end, a transplant is required, provided an organ can be located: In 2018, of the roughly 95,000 Americans waiting for a new kidney, only 25 percent managed to obtain one.

That December, Slayman had become one of the lucky 25 percent. His surgery, performed by a veteran Massachusetts General surgeon, Tatsuo Kawai, was frictionless, the postsurgery complications apparently minimal. Slayman was able to go back to work full-time. But within three years, familiar symptoms started to reappear: the swelling, the fatigue. Tests revealed scarring on the donor kidney and early evidence of recurrent diabetes. “It was clear to me,” Williams told me, “that the organ wasn’t going to survive for many more years.”

(Scientists are trying to resurrect mostly dead organs—here’s why.)

Once again, Slayman found himself thrust into a punishing cycle of dialysis and declotting; later, doctors started him on a course of anticoagulants and installed a new fistula on his upper thigh. Nothing seemed to help. Instead, more worrying signs emerged, like hyperkalemia, or abnormally high potassium levels, which left Slayman breathless and sent him racing to the local emergency room for treatment.

“He had to undergo a lot of interventions that required anesthesia and long hospital stays, and I remember him saying, ‘Doctor, I’m not sure I can go on like this,’” Williams told me. “He was considering withdrawing completely from dialysis. And we knew that would have been a death sentence.”

Which brought Williams to the idea of xenotransplantation and his conversations with eGenesis. Williams trusted the scientists at the company; he’d visited their labs himself and had marveled at what he saw there. Still, he knew his patient would likely have reservations. Like Slayman, Williams is Black, and his mind went instantly to the infamous Tuskegee experiments, in which the U.S. government conducted a 40-year study of hundreds of Black men with syphilis but intentionally hid their diagnoses and withheld treatment via penicillin when it became available. “You have to understand that what happened at Tuskegee is hardwired in African Americans in the U.S.,” Williams said. “It has created deep fear about being used as a guinea pig.”

Over the course of several informed consent meetings, Williams was as clear with Slayman about the hazards of undergoing a cutting-edge procedure as he had been about the hazards of doing nothing at all. It would not be easy. He would have to be brave. But Slayman said he understood. In conversations with his family, his daughter Pia Slayman later recalled, her father was “confident about how much of a success the surgery would be. So I couldn’t do anything but support him.”

The last informed consent session occurred in early 2024, shortly before the transplant surgery was scheduled to take place. Williams told me that halfway through, Slayman burst into tears. “He said, ‘I want to do this, but I want you to be there for me. To take care of me.’ And I promised I would. It was such a poignant moment, because Mr. Slayman was about to embark on a trip through truly uncharted waters. I could navigate, but he was going to have to be the pioneer.”

ALTHOUGH IT FEELS cutting-edge today, the science of kidney xenotransplantation stretches back decades and originated in part with the work of a gifted Tulane University doctor and professor named Keith Reemtsma. In the early 1960s, Reemtsma, a cardiothoracic surgeon by training, began planning a series of animal-to-human surgeries involving kidneys taken from laboratory chimpanzees. The idea was not unprecedented: For decades, scientists had been transfusing animal blood into—or grafting animal skin onto—human patients. The kidney, and the use of immunosuppressants in the human recipients, would merely represent a step-up in scale and complexity. A few years later, Reemtsma was vindicated when one of his patients survived approximately nine months with a chimpanzee kidney—a promising feat in an era when the stakes for patients with failing kidneys were even higher than they are today. There was no widespread access to dialysis treatment, and there was no national donor database for kidney transplants.

The euphoria was short-lived. In the 1960s, kidney disease had already reached crisis scale in the United States, and even if xenotransplantation could be perfected—a big if, considering 12 of Reemtsma’s 13 patients lasted no more than eight weeks on the chimpanzee organs—how could scientists possibly secure enough primates? A hard-to-come-by solution simply didn’t make sense, says Robert Montgomery, a transplant specialist at New York University Langone Health and himself the recipient of a donor heart. You also had the animal welfare angle: “People like Jane Goodall have added so much to our understanding of how similar we are to primates,” he said.

Finally, Montgomery added, there was the arrival of AIDS, which is believed to have originated in apes. “Having a donor species that is closer to humans on an evolutionary scale is going to make it easier to get a good result,” Montgomery told me. “But by the same token, it’s also easier to pass a pathogen from a primate to a human” than it would be with another animal.

Like, say, a pig.

Despite being notably intelligent creatures, pigs tend not to be viewed with any particular reverence by most people, E.B. White notwithstanding: By one estimate, more than a billion of the creatures are slaughtered and eaten by humans every year. And pigs breed with alacrity, typically twice a year and sometimes three, with litters averaging eight to 12 piglets. This is one of the reasons that, beginning in the 1990s, many researchers in the xeno field began to gravitate away from primates.

But the shift presented its own unique obstacles, the most vexing of which was represented by a porcine antigen known as galactose oligosaccharide, or alpha-gal for short. This antigen, found in pigs, is not present in the human body, which will attempt to rid it from the bloodstream by producing antibodies that bind to the antigen. When this occurs after an organ transplant, it usually prompts the acute rejection of the donor organ. Antibiotics and immunosuppressants can help, but not in the long term, as waves of researchers reluctantly concluded. They realized they’d need to remove the alpha-gal antigen from the pig kidney, a time-consuming process.

An efficient solution to that issue was pioneered in 2012, when scientists Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna patented a technology known as CRISPR-Cas9—an oft-used simile likens it to “a pair of molecular scissors.” With CRISPR, researchers made “cuts” in human and animal genetic code, thus replacing disease-causing mutations and fundamentally changing the way genes were expressed.

In the U.S. and Europe, any experimental intervention must pass through two stages before it is made publicly available. In the preclinical stage, a drug or surgery is tested in the lab; in the second, providing the results are acceptable to regulators, researchers can move on to humans.

In 2017, a year before Rick Slayman received a human donor kidney, scientists affiliated with eGenesis opened a preclinical trial on several long-tailed macaques that were outfitted with lab-modified pig kidneys informally dubbed “knockouts”—a nod to the antigens removed via the gene-editing process. One monkey lived nearly 300 days.

“We had a meeting with the FDA, and we basically asked, ‘What would you need to see in order for us to move [to the next stage]?’” recalled eGenesis CEO Curtis. “They gave us a figure of 12 months’ survival in a monkey. I was like, ‘Well, look, we’re clearly moving in the right direction.’”

But eGenesis was not alone in its pursuit of FDA approval. Revivicor, a subsidiary of the biotech firm United Therapeutics, had simultaneously been working on its own modified porcine kidneys. At a high level, the engineering methods employed by eGenesis and United Therapeutics, which is publicly traded and designated as a public benefit corporation, appear remarkably similar. Scientists at each company start by editing porcine fetal cells to remove the expression of dangerous antigens before cloning the cells via nuclear transfer—a technique that yields embryos of matching genetic composition. Healthy embryos are then implanted into female pigs, which give birth to litters of piglets with identically edited cells.

But there the resemblances in approach end. United Therapeutics for its part knocks out just four porcine genes, preferring to utilize a breed of pig, the Landrace, for its fertility and litter size. Conversely, eGenesis makes 69 different edits to its cells, 62 of which are knockouts and seven of which are additions from the human genome. And those cells are different in origin: eGenesis favors relying on the smaller Yucatan pig breed, whose organs more closely match a human’s in size.

In September 2021, NYU Langone was granted permission by regulators to transplant a United Therapeutics–edited pig kidney into a brain-dead human patient. (As a brain-dead patient is considered legally dead, the body would be supported by a ventilator during the procedure.) Montgomery, of NYU Langone, was tasked with carrying out the surgery. “I have spent most of my career trying to increase the number of living organ donors,” Montgomery told me, noting that the annual number of living human kidney donors has been a flat line for 15 years, hovering at 6,000. “It was hard not to see the transplant as a breakthrough. You could sense the enthusiasm. I felt it too.”

(Pig brains partially revived hours after death—what it means for people.)

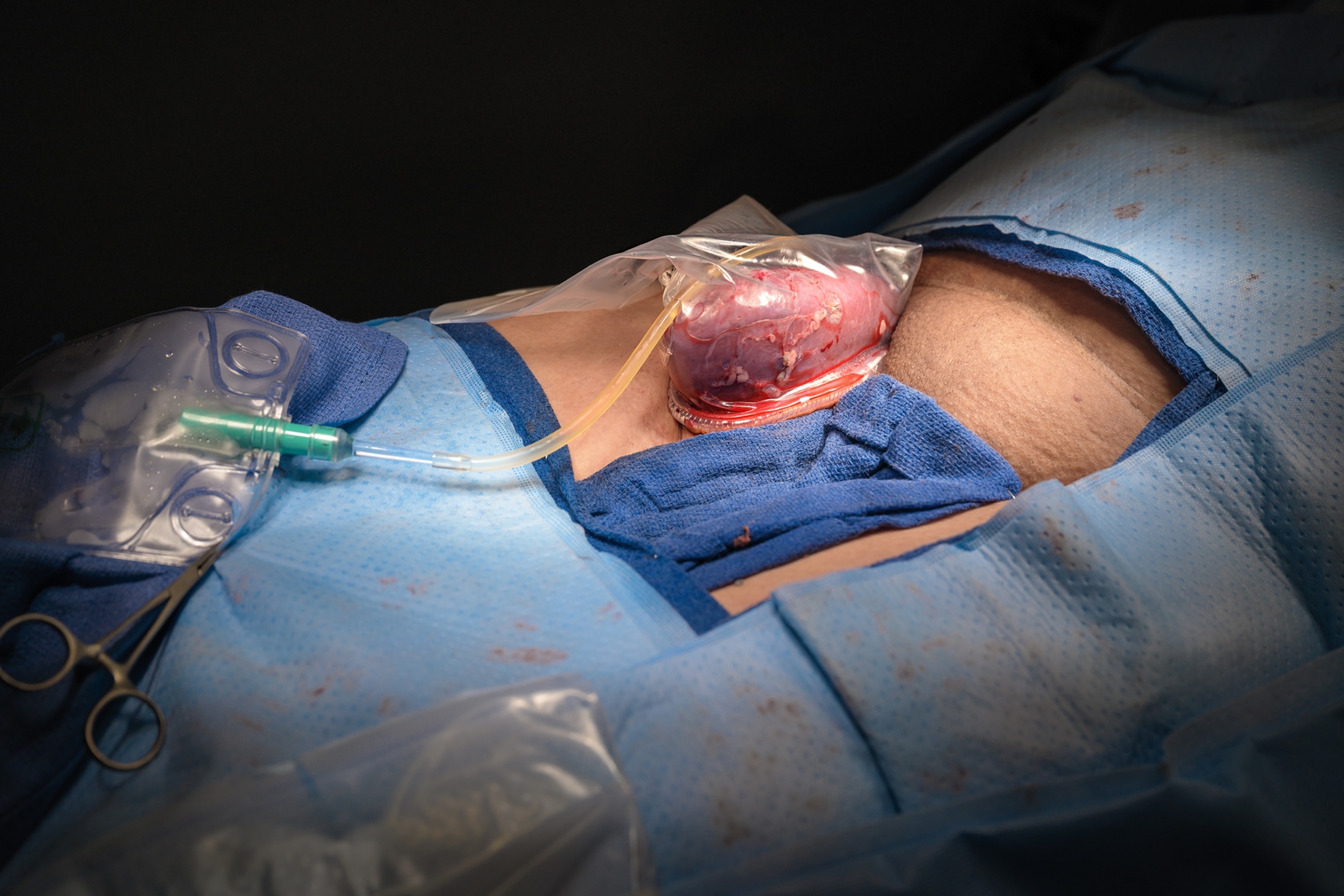

In October of 2021, NYU Langone went public with the news: The xenotransplanted kidney had been attached by a network of blood vessels to the patient’s upper leg, where it started to function immediately, creating urine for nearly three days.

Just one major step remained: a test on a living patient.

WITHIN HOURS OF Slayman’s final informed consent meeting at Winfred Williams’s office, gears began turning at the eGenesis farming facility.

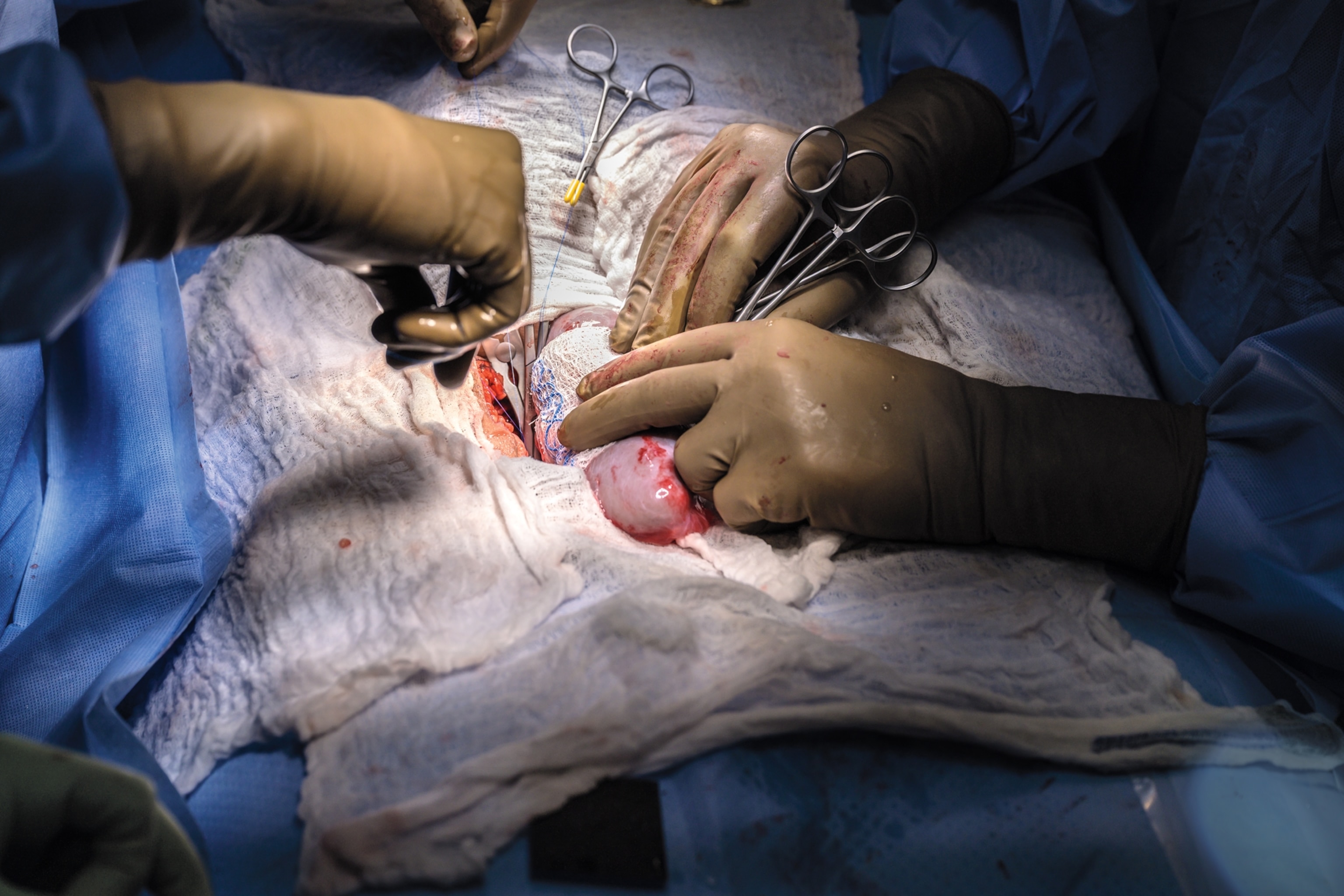

As Bjoern Petersen watched, the small pig was loaded into the van, which raced down the road and onto the freeway. The ensuing cross-country journey was a “whole logistical dance,” Mike Curtis told me. Traveling east through the night, the pig reached a veterinary center in western Massachusetts. There, both its kidneys were removed by Slayman’s surgical team, with euthanasia administered postprocurement. By noon, the organs were packed into a refrigerated box and placed in the back of a different truck, pointed this time toward Boston. At Mass General, Slayman—who had already been prescribed a strong course of immunosuppressants—was put under and prepped for surgery while his family waited anxiously in the waiting area. At 1 p.m., on March 16, the procedure commenced.

From his position in the operating theater, Williams watched as colleagues Leonardo Riella, Mass General’s medical director of kidney transplantation; Tatsuo Kawai, who’d performed Slayman’s original kidney transplant years earlier and had worked with Riella to coordinate the FDA approvals; and Nahel Elias, surgical director of kidney transplantation, carried out the procedure. They all knew the difficulties that Slayman’s long struggle with kidney disease and hypertension would present. “His whole vascular anatomy had changed,” Williams said. “He had very calcified, very hardened vessels, and you can’t just crack open calcified vessels and make them work. You’ve got to find the right anatomic distribution. Plus, you need to remember that Mr. Slayman was a big guy, and the vessels that were available for attachment to the donor kidney were sort of deep within his abdominal cavity.”

In the days leading up to the operation, Pia Slayman reminded herself how confident her father had been that the surgery would be a success. When she entered the recovery suite that evening, she took her father by the hand and wept with relief. Although he grasped the history-making meaning of the procedure and the interest it would inspire in reporters, Slayman told hospital staff he’d prefer to stay out of the limelight; gamely, he agreed to pose for a few photos with his family before returning to the house that he shared with his fiancée, Faren Woolery.

The following week was hard: Within a few days of the surgery, Slayman was diagnosed with symptoms of acute rejection and treated with what Williams described as the same antirejection medication “we would use in a garden-variety human transplant.” The treatment was effective.

But 51 days posttransplant, Slayman returned once more for an appointment with Kawai and Riella. The doctors noticed signs of volume depletion—he was losing more nutrients and fluid than he was taking in. Slayman was hooked up to an IV to boost fluid volume, Williams told me, “and he had a magnesium infusion to address some low levels.”

That same day, Slayman and Woolery left Mass General and picked up groceries near their home in the Massachusetts town of Weymouth. They made stops at two stores. Slayman accompanied his fiancée into the first one but begged off when it came to the second. He didn’t feel up to it, he told Woolery. That night, after eating dinner and watching television together, the couple went to lie down. In the bedroom, Woolery noticed Slayman’s breathing had grown labored and shallow around 11:30 p.m. Around midnight, Slayman went into cardiac arrest. Woolery called 911, then dialed Williams, who told the EMT crew by phone to take Slayman to the nearest emergency room. Williams rushed to meet them at South Shore Hospital, in Weymouth, but their combined efforts at resuscitation came up short—Slayman passed away in the early morning of May 11, at the age of 62.

In the hours after Slayman’s death, his family huddled with Williams at South Shore for a debriefing. Slayman’s brother and fiancée were on hand. Williams explained that it was critical to understand what had happened to Slayman, given his relatively healthy status earlier in the day. After making a call to Slayman’s mother, the family granted permission for an autopsy. The results, which were published earlier this year, revealed that the issue had been Slayman’s heart, not the kidney.

“What we think happened,” Williams said, “is that because of his severe cardiac disease, he had arrhythmia, and he suffered an arrhythmic event that led to his death.”

The tissue of the kidney was healthy, and although there was “residual evidence” of the initial rejection symptoms, “there was no acute kidney failure that would have been cause for Mr. Slayman’s demise,” Williams said. “Bottom line is that the xenograft was functioning reasonably well.”

It can be difficult to see it that way, of course, given that recipients of a kidney from a deceased human donor can live 12 years, and recipients of an organ from a living donor up to two decades. Slayman managed less than two months, with a handful of medical interventions in between. And Lisa Pisano, who in April 2024 became the second living patient to receive a modified pig kidney, hers from United Therapeutics, passed away three months after her transplant due to heart issues. But Montgomery, who led Pisano’s surgery team, offered a useful reminder.

“Patients on the edge of dying already—patients we’re trying to rescue with a brand-new technology we’re still refining—are just not good indicators of how the science will fare in the long term,” Montgomery said. “We kind of set ourselves up with the most difficult scenario.”

Several days after Slayman’s passing, Williams recalled, he received an invitation to speak at his funeral, held at a Baptist church in Milton, Massachusetts. He wasn’t sure how he would be greeted. His mind traced back to the lingering legacy of the Tuskegee experiments. “When you walk into this kind of congregation, you never know how you’re going to be received,” he told me, “because there may be this suspicion, even if it’s unspoken, that they experimented on this individual—like, This is what they do to Black people.”

At the church, Williams was joined by Slayman’s entire medical team, and he began his remarks by introducing Kawai. Immediately Williams’s fears about his reception vanished. “Before I finish speaking his full name, the entire congregation gets up and gives us a standing ovation. It was just unbelievable, the energy.”

Recounting to me what he told the packed church, Williams held back his tears.

“I said, ‘He’ll go down in the pantheon of medical history,’” he told me. “I wanted them to understand that he had provided new hope for patients everywhere.”

IN THE WAKE OF SLAYMAN and Pisano’s operations, eGenesis and United Therapeutics, along with hospitals around the country, fielded a torrent of inquiries from patients who had spent years on a list for a human donor kidney. It didn’t matter that FDA regulators were still only authorizing expanded access trials. News of the transplants had opened the floodgates. “People were asking, ‘Why not me?’” Curtis recalled. “‘My health is already declining. Why should I have to wait?’”

Curtis, for his part, could only respond with the truth: eGenesis was working as hard as possible to get the technology to more patients. “I’d say, ‘We want the same thing, but we want to do this right,’” he told me. And doing it right would require approval for trials on healthier patients, he went on—patients like Tim Andrews.

A former supermarket manager from Concord, New Hampshire, Andrews, 67, had for two years undergone thrice-weekly dialysis—a process that often took six hours, including travel and prep time, and left him exhausted and weak. When I spoke with him about the difficulty of dialysis, he recalled his appetite disappearing as he dealt with near-constant nausea. He began to stare at the likely reality of never receiving a human organ and of repeating this emotionally draining routine for the rest of his life. As had been the case for Slayman, it was a daunting thing to try to accept.

But last August, Andrews was offered the opportunity to undergo xenotransplant surgery at Mass General as part of a new three-patient, FDA-approved trial launched by eGenesis. If he agreed, he’d have the chance to start over. To have, as he put it, “a second chance.” His family was leery; his sister, a nurse, warned him about the risks. But he was adamant.

“This is not how I want to go out—I want to do something,” Andrews recalls saying. “And I knew that I might die right off. And I said to my wife and to the Mass General team, ‘If I die and you learn something, so be it. And if I don’t and I get to give people hope—that’s what I really wanted.’”

In January, Andrews underwent his transplant, with Kawai leading the surgery team once more. Andrews walked out of the hospital, beaming, wife Karen at his side. Nothing was certain, he knew. Still, he had what he’d hoped: a new lease on life. “Every day,” he said, “is a new day.”

When we spoke in March, Andrews’s recovery was progressing as planned. He goes to Planet Fitness twice a week, regularly takes his nine-year-old German shorthaired pointer on walks, and helps his wife around the house by vacuuming. If all continues to go well, he said, next year the couple will board a plane and visit her relatives in northern Italy.

With his energy returning, Andrews is also trying to serve as inspiration for the tens of thousands of people affected by the organ donation crisis. Every Wednesday night, he meets online with a support group for transplant patients. They encourage one another on their journeys, and, of course, they ask about his porcine kidney. “I want to give that hope to everybody else that’s on dialysis or is struggling with kidney disease,” he said.

This—an escape from dialysis, a whole-body reinvigoration—is the future. For Andrews, but potentially for dozens of people in the coming years, should the clinical trials expand to a field of 50 patients as planned. And both Andrews and Curtis recognize none of it would be possible without Slayman and Pisano, who proved that the potential of genetically modified kidneys was more than hypothetical and a real solution worth pursuing.

“To get here, we owe so much to brave people like Mr. Slayman, and to all scientists on whose shoulders we stand,” Curtis told me. “We have been fortunate to enter the field when we have, because we’re able to leverage decades of progress and research and integrate it all into making this thing a reality. You kind of have to pinch yourself. But here we are.”

(Pig brain cells may have cured a sea lion's epilepsy—are humans next?)

Matthew Shaer, based in Atlanta, is a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine. This is his first piece for National Geographic.