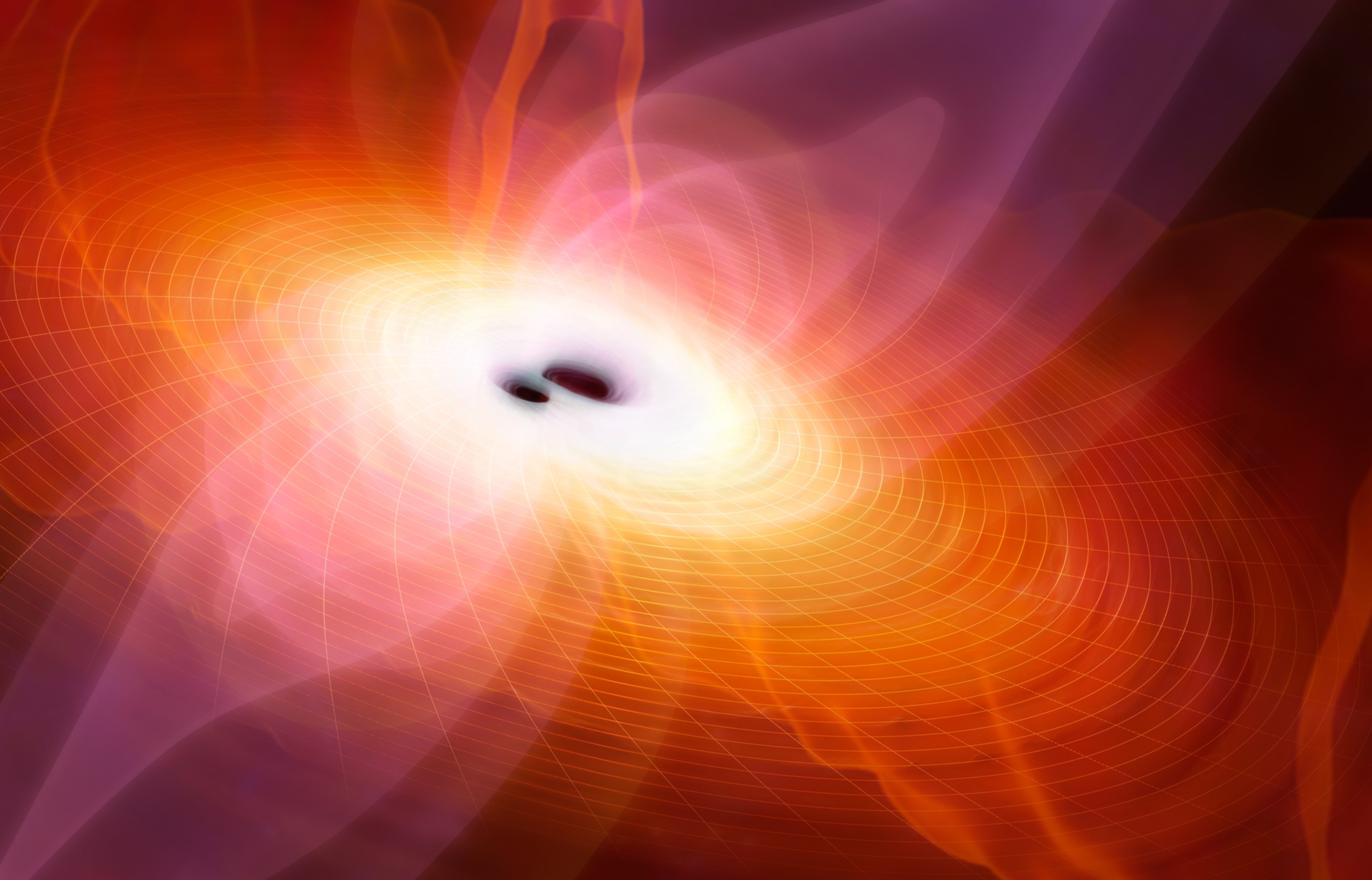

Scientists record a black hole collision they weren’t sure was possible

The largest black hole collision ever recorded has scientists' jaws on the floor — and scratching their heads.

A pair of newly-discovered record-breaking black holes has scientists simultaneously popping the champagne and scratching their heads. The massive duo are the largest ever recorded at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which was built to detect ripples in the fabric of spacetime caused by the collisions of massive objects. These enormous outliers are challenging theorists to figure out just how they grew to such titanic sizes.

(Black Hole Hosts Universe's Most Massive Water Cloud)

“We don't think black holes form between about 60 and 130 times the mass of the sun, and these two seem to be pretty much slap bang in the middle of that range,” says Mark Hannam, a physicist at Cardiff University in the UK and a LIGO team member.

(Every Black Hole Contains Another Universe?)

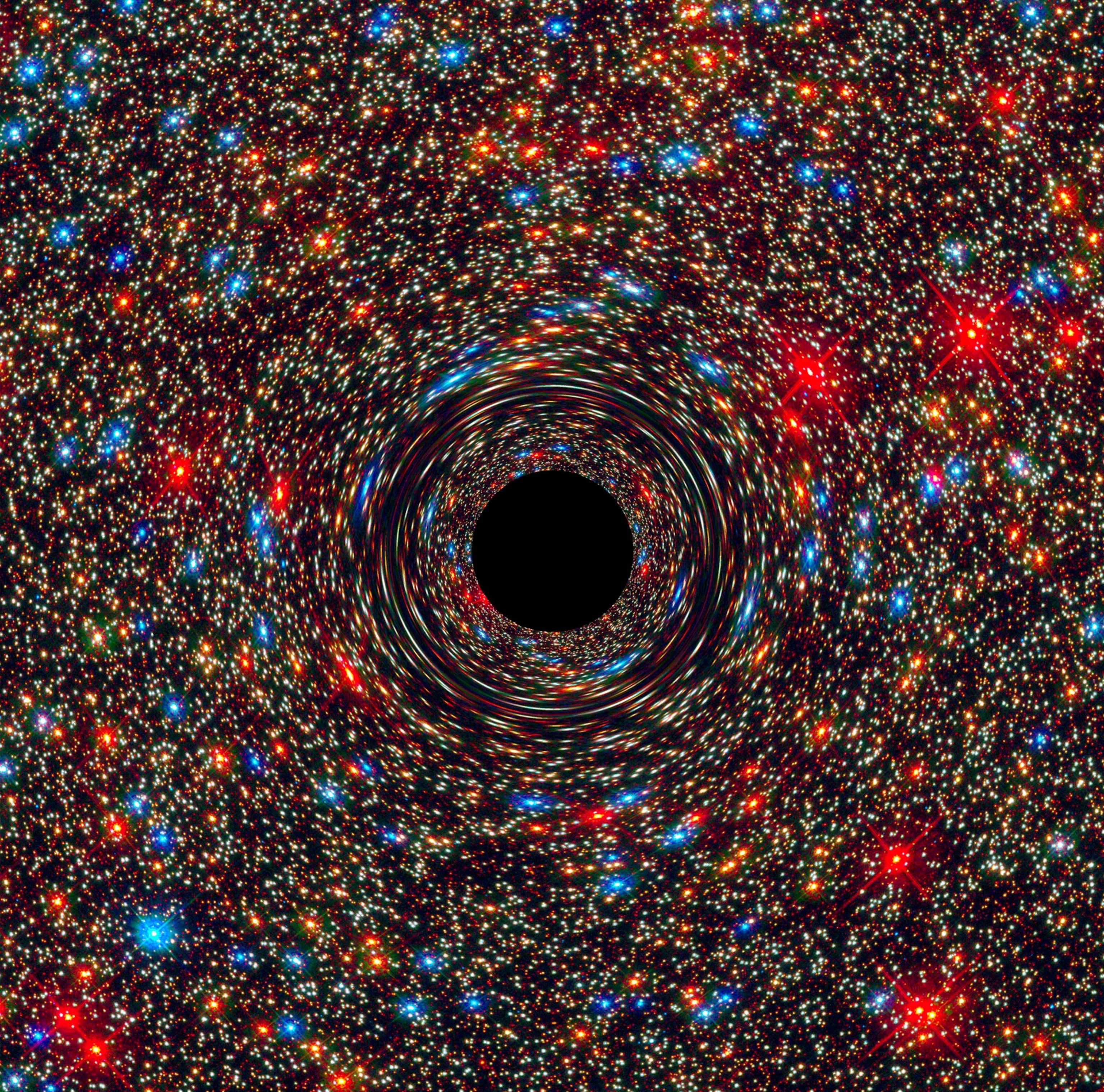

Your normal everyday black hole is thought to be born during the death of a giant star, when the star’s weighty core collapses down into an infinitesimal point with such strong gravity that nothing, not even light, can escape it. But the physics of this process gets wonky for especially huge stars. Once their cores weight more than around 60 solar masses, the collapse becomes so violent that the entire star is blown to smithereens, leaving nothing, not even a black hole, behind.

(Mini Black Holes Zip Through Earth Every Day?)

Yet LIGO is now spotting more and more black holes within this ‘forbidden’ zone, including the newest behemoths. They are thought to be 103 and 137 times the sun’s mass, according to a paper posted July 13 to arXiv.org, but each has enough uncertainty in their measured properties that they could both be inside the prohibited range. When they met and merged out in the deep dark universe billions of years ago, they created an even larger monster tipping the scales at between 190 and 265 solar masses, the most massive beast LIGO has ever seen. As the observatory captures gravitational waves from more such events, researchers will be able to tease apart the mystery of their creation and perhaps learn whether they have a connection to the astoundingly huge black holes lurking in the centers of galaxies.

Black holes were thought to come in two flavors. This discovery is a strange third

For a long time, black holes were known to come in just two versions—approximately sun-sized and galactic. Most of the roughly 300 black holes LIGO has detected so far fit into the first category: They are between a few and several tens of times the sun’s mass and are believed to have formed after a gargantuan star exploded as a supernova, leaving behind a dense remnant that inexorably sucks in anything that gets too close.

The second version is a much more gargantuan beast. Telescopes have spotted black holes in the centers of nearly every galaxy; gravitational monstrosities weighing 100 million solar masses or more that appear to regulate star formation within these galaxies. Nobody is quite sure how these immense devourers got so big. Did they start out as sun-scale black holes and then somehow grow to extreme size? Or was there another story behind their creation?

The existence of black holes in the intermediate range—somewhere between 100 and 100,000 times the sun’s mass—would help bridge this gap and perhaps help explain whether small black holes were turning into larger ones. But, until recently, physicists had never seen one. To great fanfare in 2020, LIGO researchers announced that they’d found a black hole duo with masses 66 and 85 times that of the sun, whose smash-up produced a giant with around 150 solar masses. The finding for the first time showed that black holes could cross into this threshold of intermediate mass, though theorists are still debating exactly how that happened.

The problem is that when a gigantic star has a core that weights between 60 and 130 times the sun’s mass, it can reach blazing temperatures nearing 300 million degrees Celsius during the end of its life. At that point, particles of light spontaneously transform into electrons and their antimatter counterparts, positrons. These particles can no longer hold up the star’s heavy outer layers, which come crashing down with such ferocity that the core is completely obliterated. No black hole, or anything else, results.

Physicists have speculated about a few possibilities to explain what they’re seeing with LIGO. For one, their theories of stellar evolution might be wrong and perhaps something can survive the severe core collapse of humongous stars. The other possibilities involve smaller black holes growing into larger ones via some kind of two-step process, says astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan of Yale University in Connecticut.

It could be either that two star-sized black holes came together and combined to form heavier behemoths or a small black hole was created and then sucked down gas and dust to balloon into a more massive beast. “The question is: What are the cosmic environments and conditions where such things can happen?” Natarajan asks.

One major clue might lie with the two new objects, which are spinning around like a top at close to the upper limit that scientists think they can spin. They have the fastest rotations of any black hole LIGO has ever seen. Some researchers have posited such spins could arise when smaller black holes meet, merge, and spin each other up.

But Natarajan thinks perhaps something else is going on here. Because if the colliding black holes were spinning in opposite directions (and there’s a good chance they were) the merger black hole would have produced a slower-spinning object. She favors the idea that smaller black holes were born in dense stellar clusters full of gas and dust. As that star-sized black hole bounced around inhaling material like water going down a drain, it could have grown and spun up to the extreme rotation seen in the new objects. She and her colleagues are working to calculate the exact outcome of such a feasting process in stellar clusters.

Scientists aren't done searching for enormous black holes

Future upgrades to the LIGO detectors will make them more sensitive, letting them uncover even more enormous black holes and measure their properties more precisely. Along with gravitational wave detectors in Europe, Japan, and eventually India, researchers will be able to pinpoint black hole events better on the night sky, allowing telescopes to scope those areas out and see if there’s, for instance, a dense star cluster that might favor one formation mechanism or another.

Researchers are also looking forward to instruments such as the Cosmic Explorer and Einstein Telescope, expected to be operational in the mid-2030s or 40s, which will be able to see black hole mergers that occurred much earlier in the universe’s history. Such gravitational wave observatories might be able to capture events when galaxies were first forming, potentially providing insights into how their central black holes became so gargantuan, along with better data on small and intermediate black holes.

“There's just so many black holes littered in the universe,” says Natarajan. “The fact that we're starting to bridge these scales, I think that's super exciting.”