Industrial Fishing Occupies a Third of the Planet

Using satellite data recently made public, conservationists may be able to manage the massive industry.

How do you study the world's more widespread predator? By spying from space.

When a team of researchers set out to see how prevalent industrial fishing was around the world—who was fishing where and when—they were met with a dearth of information.

They lacked access to vessel monitoring systems closely held by regional fishery managers, says Juan Mayorga, a marine data scientist from National Geographic's Pristine Seas project. And that information would have shown only pieces of the puzzle.

To circumvent this obstacle, Mayorga and a team of researchers took a step back—way back—and tracked marine vessels from space, using satellites to learn where industrial fishing vessels fished and when.

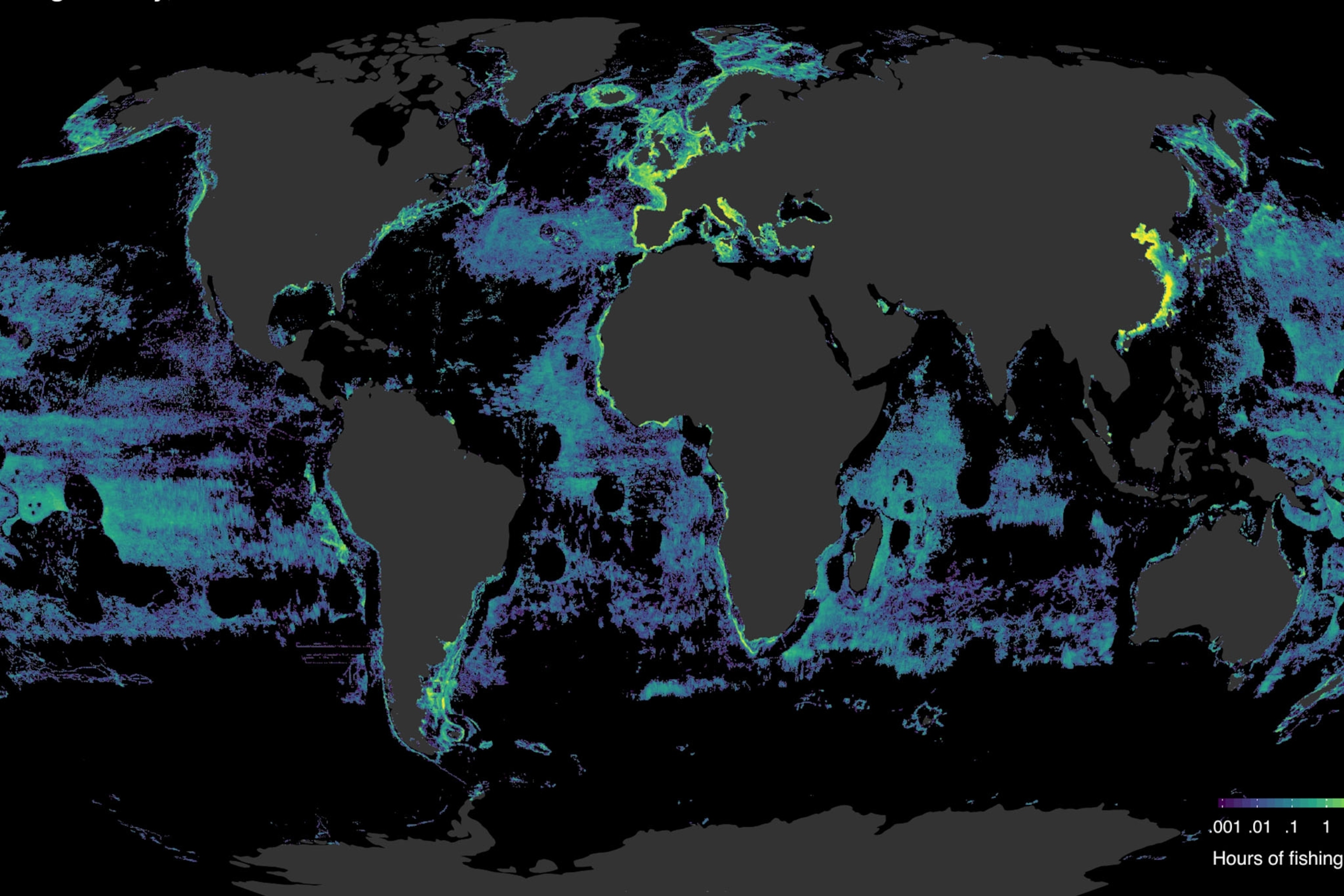

They found the footprint left by the industry was staggering.

More than 55 percent of ocean surface is covered by industrial fishing, they found. That's more than four times the area covered by agriculture.

Industrial fishing has been responsible for harmful environmental impacts. Overfishing can deplete resources, many animals like dolphins and sea turtles are products of bycatch, and the massive vessels used require large amounts of CO2-producing fuel.

But looking at the industry on a global scale may lead to increased transparency and accountability to ensure fisheries are more sustainably managed, the researchers say.

Where Is Fishing Taking Place?

The study, published in the journal Science, looked at over 70,000 industrial vessels measuring from six to 146 meters, which encompasses more than 75 percent of the large-scale industry.

From 2012 to 2016, researchers watched the ships' movements down to the hour, by sifting through 22 billion signals from ships' automatic identification systems or AIS.

AIS was originally created to prevent ship collisions by broadcasting a vessel's identity position, speed, and turning angle every few seconds.

"Those AIS messages that are broadcasted are publicly available via satellite," says Mayorga. "We then combed through [the signals] with sophisticated computing capabilities provided by Google and machine learning algorithms."

From this, says Mayorga, he was able to glean information about the characteristics of each vessel, which revealed what type of fishing was taking place.

Longline fishing, a type of fishing in which a line with baited hooks is dropped into the water, was found to be the most prevalent. Trawlers were frequently spotted in the North Sea and off the coast of China.

The data also provided useful information by showing activity on the high seas. As opposed to coastal waters under a country's jurisdiction, the high seas are less closely monitored.

China, Spain, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea accounted for 85 percent of fishing in the high seas.

When Is Fishing Taking Place?

"You can't approach getting into the head of a fisherman the same way you can get into the head of a fish," says Douglas McCauley, a marine biologist from the University of California at Santa Barbara who was not involved with the study.

Unlike sea animals, the satellite data found humans were less influenced by environmental factors. But that doesn't mean there weren't patterns.

Researchers saw a massive dip in activity among Chinese vessels during the Chinese New Year. And they saw a massive dip among other vessels over the Christmas and New Year holidays.

As expected, regions that implemented seasonal fishing moratoriums also saw a dip in fishing during those periods.

When fuel prices spiked, the study found fishing was largely uninfluenced. McCauley suspects fishing subsidies, funding the World Trade Organization tried but failed to curb last December, are therefore contributing to overfishing.

Watchdogs Protecting Fish

In addition to National Geographic, the study was supported by researchers from the University of California Santa Barbara, Dalhousie University, Stanford University, and Global Fishing Watch (GFW), a collaborative non-profit supported by Oceana, SkyTruth, and Google that aims to increase transparency. (Learn more about SkyTruth.)

"The GFW introduces a whole new dimension in the fight against illegal fishing, and for transparency in offshore fishing," says Daniel Pauly, a marine biologist from the University of British Columbia who was not involved with the study.

By making the study's data publicly available, the GFW claims low-cost marine reserves can be more easily implemented.

Marine reserves act like a bank for fisheries, allowing a healthy stock of fish to flourish in off-limits areas. Conservationists have long argued for implementing more and larger marine reserves, but face opposition from the fishing industry.

"This [global dataset] makes any decision making or negotiating transparent," says Mayorga.

Conservationists say they will be able to prove what regions are less frequented by fishers and already prime to be a reserve.

Sustainable Management

"My first job was as a fisherman. You can appreciate how hard that work is," says McCauley. "You see each of those stories locked in a data set. It's an industry that's increasingly important as we confront food security and nutrition shortfalls."

He believes that by eliminating fishing subsidies and more strategically regulating fishing on a global scale, it's possible to sustain current levels of fishing without depleting resources.

"None of this was really possible until we had this database made publicly available," he adds.

If conservation measures are applied to industrial fishing, Mayorga sees a role for AIS signals to be used to keep industry accountable.

"The biggest problem is the traceability of the resources," he says of implementing regulations. "You have to keep track of where the fish is coming from when it lands. That's a big issue for sustainability."

His next goal, he says, is to monitor and track smaller ships.