Cameron Parish, Louisiana — Johnson Bayou Fire Chief Rony Doucett remembers driving down Louisiana Highway 82 in the 1970s. Back then, he estimates, there was about a quarter-mile stretch of beach between the highway and the water.

Today that road, also called the Gulf Beach Highway, is in many stretches just a few steps from the ocean.

“Now it’s just water, beach, road,” Doucett says.

The people living in southern Louisiana must grapple with two kinds of natural disasters: the slow ones, such as coastal erosion, that chip away at the state over years, and the fast ones, such as hurricanes, that destroy homes and engulf chunks of land in a matter of hours.

As members of the National Guard, volunteers, and other first responders rushed into southwestern Louisiana after it was struck by Hurricane Laura last month, so too did the scientists who are urgently trying to understand how the state’s landscape is changing.

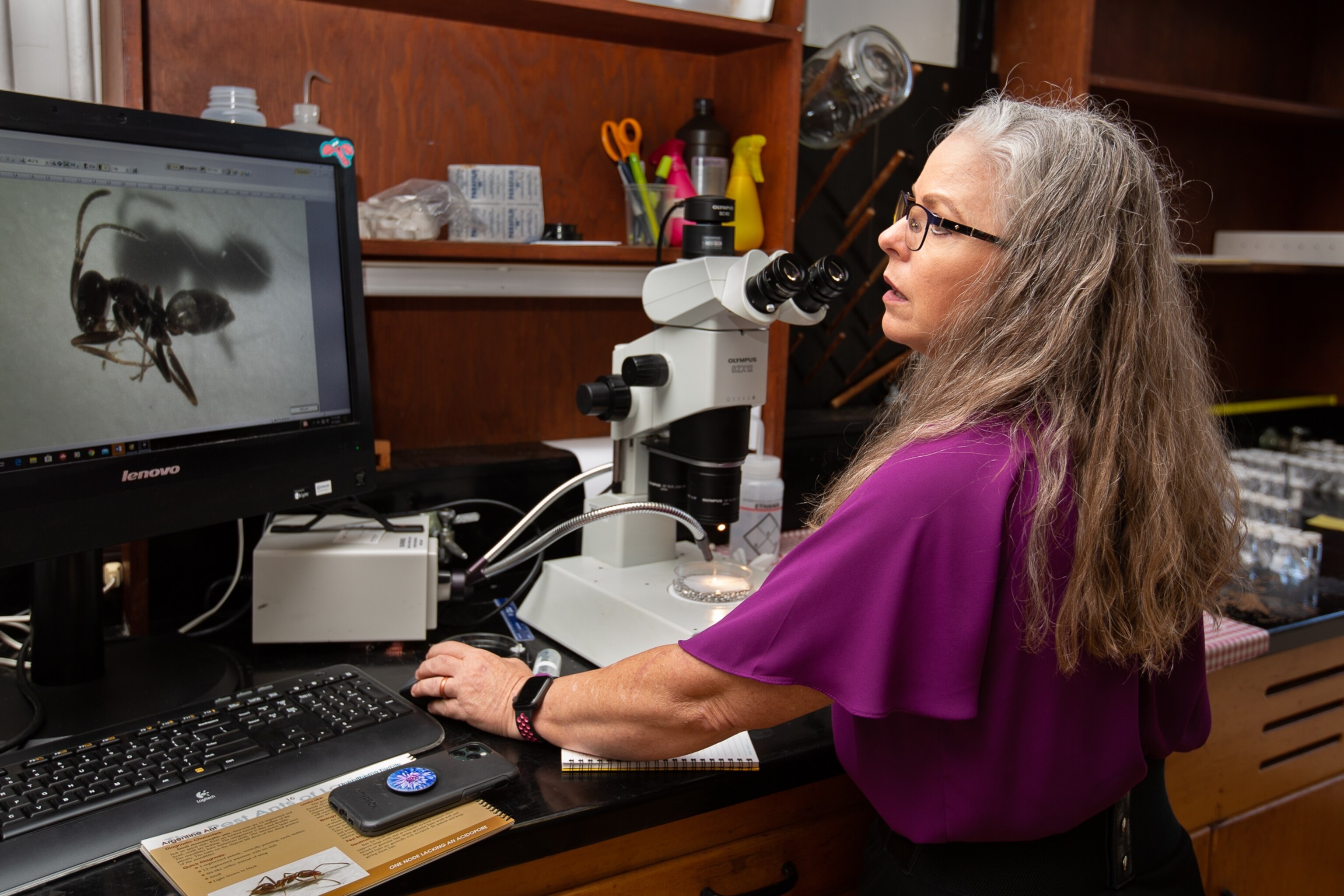

“This is an opportunity that’s fleeting,” says Linda Hooper-Bùi, a disaster ecologist at Louisiana State University. “It can really simplify an ecosystem, and we can learn how [the ecosystem] reassembles.”

A sinking state, rising seas, and eroded land

For years, scientists have known that the Mississippi River Delta, a region that includes most of south Louisiana and part of Mississippi, is sinking. The region consists of a vast area of dams and levees that, when working, keep the Mississippi River from flooding into places it shouldn’t. Those same dams and levees also prevent the river from replenishing itself by dumping the sediment it’s naturally dumped into the delta for centuries.

This, combined with the oil and gas pumped out of the ground, is causing the area to subside into the Gulf of Mexico.

One paper published in 2017 estimated that the Louisiana coast sinks at a rate of eight millimeters per year. Seas also are rising quickly around the delta, about 3 millimeters a year, compared to the 0.6 millimeters seen 600 years ago, when the delta was still growing. The combined effect of the sinking and the rising water is a rapidly disappearing coastline.

“The marsh edge erosion is a continuous process mainly induced by small wind waves,” says Louisiana State University Ph.D. student Yadav Sapkota. “These waves continuously tear at the marsh edge, causing the soil to collapse into the bay, eventually converting the entire marsh into open water.”

But after large storms, that steady drumbeat of wetland loss speeds up. “After hurricanes, more chunks fall off,” says Sapkota’s adviser, Louisiana State University coastal scientist John White.

Two days after Hurricane Laura made landfall on August 27, White and Sapkota were surveying erosion in Louisiana’s Barataria Bay, where coastal islands of marsh grasses jut out of brackish water like islands of prairie grass. Even from a distance, White and Sapkota can see the effects of Hurricane Laura’s intense winds in the flattened grass, normally upright.

After visiting sites once staked at a marsh's edge and measuring how far the grass has receded, Sapkota concludes that the storm made erosion in the region 63 times faster compared to long-term rates. In the four years the researchers have been sampling, the marshes have been diminished by an average of 0.35 centimeter every day. During the storm, those same marshes lost 22 cm a day.

Barataria Bay is some 200 miles east of Cameron, where the hurricane made landfall, but it still felt 40-miles-per-hour winds that accelerated erosion. Along with sinking land and rising seas, hurricanes are “a large threat to wetlands even when they don’t strike directly,” Saptoka noted a few days later via email.

To see the ecosystem, look at ants

While White and Sapkota research how quickly Louisiana is eroding into the Gulf, Hooper-Bùi is interested in how the critters roaming it survive a storm. Ants in particular, she says, can reveal how the ecosystem is recovering because they, like people, return to their environment as communities, not individuals.

“They’re an indicator of what’s happening right here, right now,” Hooper-Bùi says.

As Louisiana sinks and seas rise, she says people and ants are reaching tipping points where one too many floods make it unlikely a community will rebuild.

“Think of it like a game,” says Hooper-Bùi. “The ecosystem follows the rules of the game—then there’s a disturbance, someone bumps into the board or totally flips it over, but you remember where your pieces were, and you remember the rules. We think that not only are the pieces on the gameboard not really all there, they’re not even in the same room—the rules of the game have completely changed.”

After a storm, the biodiversity of an affected region is temporarily suppressed. But slowly, native species return. Randomly at first, Hooper-Bui says, and then methodically. Now the rules of who returns, Hooper-Bùi thinks, are changing.

On a trip to survey portions of southwest Louisiana, Hooper-Bùi is placing squares of PVC pipes on the beach to survey how many ants are in a given space. Using a long, hollow tube with a square compartment in the middle, she places one end in her mouth and the other on an ant, then sucks it into the compartment and transfers it to a test tube.

Hopper-Bùi is requesting emergency research funding from the National Science Foundation to return to the region and take more ant samples, but at first pass, she finds fewer ants than normal. Farther east in the town of Cameron, all of her sample sites are underwater.

One theory she’s testing is whether local ant species are able to survive storms, like invasive red fire ants, which form rafts and float on floodwaters. From initial surveys, she finds that spots normally containing as many as five species have one or none.

“Does this give invasive ants greater ability to take over?” she wonders.

Hooper-Bùi predicts that parts of the state that saw the worst storm surge will experience the same thing New Orleans saw after Hurricane Katrina in 2005: Invasive ants gained a foothold. After Katrina, Hooper-Bùi says, lingering floodwaters killed native species in the New Orleans area. Fire ants quickly moved in, and Hooper-Bui says she noticed what appeared to be more aggressive ant behavior: People who evacuated during the storm often had what looked like full body rashes, in which each large pustule was a single ant bite.

In April, Hooper-Bùi published a study documenting that phenomenon and showing that rising seas are making invasive fire ants bigger and more aggressive. Ants that might normally crawl over your foot when passing by, she says, might instead bite it—repeatedly. The behavioral trait, she thinks, stems from their sudden lack of food.

Fire ants and other insects, fish, amphibians, and reptiles can travel large distances on hurricane winds. The U.S. Geological Service charts the dozens of species seen in affected regions after a storm. Invasive species that once struggled to survive are now having an easier time making a home in the state.

“As we have warmer temperatures, we’re seeing changes in what can survive,” says Hooper-Bùi.

Long-term effects of hurricanes

While flying over Louisiana’s southwest coast the day after the hurricane, photographer Kathy Anderson captured images showing “overwash,” large stretches of coastline pushed back by the storm.

One of the worst impacts, White says, is what might happens to the carbon stored in marsh grasses. As the plants are submerged and die, they may become mud on the bottom. “If carbon gets buried in the bay, it’s OK,” White says. “But it’s unclear if that’s happening.”

The rotting plants also release carbon in the form of carbon dioxide, which escapes to the atmosphere. Like deforestation in the Amazon and melting permafrost in Siberia, eroding marshes in Louisiana reinforce climate change: With rising seas, each meter-long stretch of lost coastal marsh is releasing as much as 2,020 kilograms (485 pounds) of carbon dioxide. In a year, Barataria Bay loses eight square miles of coastal marsh, releasing an estimated 1.65 million metric tons of carbon dioxide—equivalent to the emission from more than 350,000 cars. It’s one of eight coastal basins eroding in Louisiana.

Louisianans are feeling the effects of that erosion—and of the climate change that is accelerating it. Residents of the far southern town Isle de Jean Charles were declared the nation’s first “climate refugees” in 2016 and given $48 million to settle on higher ground. Nearly a million people in the state could see more flooding resulting from sea level rise.

Hooper-Bùi likens her post-storm work in the ecosystem to “taking its pulse.”

She hopes to be back to further investigate the area’s ants, looking at how many survive and examining their diets to see if the plants upon which they depend are coming back too.

Louisiana’s environmental issues are rewriting the rules of how the ecosystem is supposed to return from a natural disaster, and Hooper-Bùi says right now it’s a “guessing game” to figure out what they are.

With more time and funding to research, she says, “It’s guaranteed we’ll discover something new. We’re searching for the new rules.”

Correction: This article has been updated to include accurate erosion rates in Barataria Bay during Hurricane Laura.