Tourists Could Destroy Venice—If Floods Don't First

Residents are abandoning the city, which is in danger of becoming an overpriced theme park.

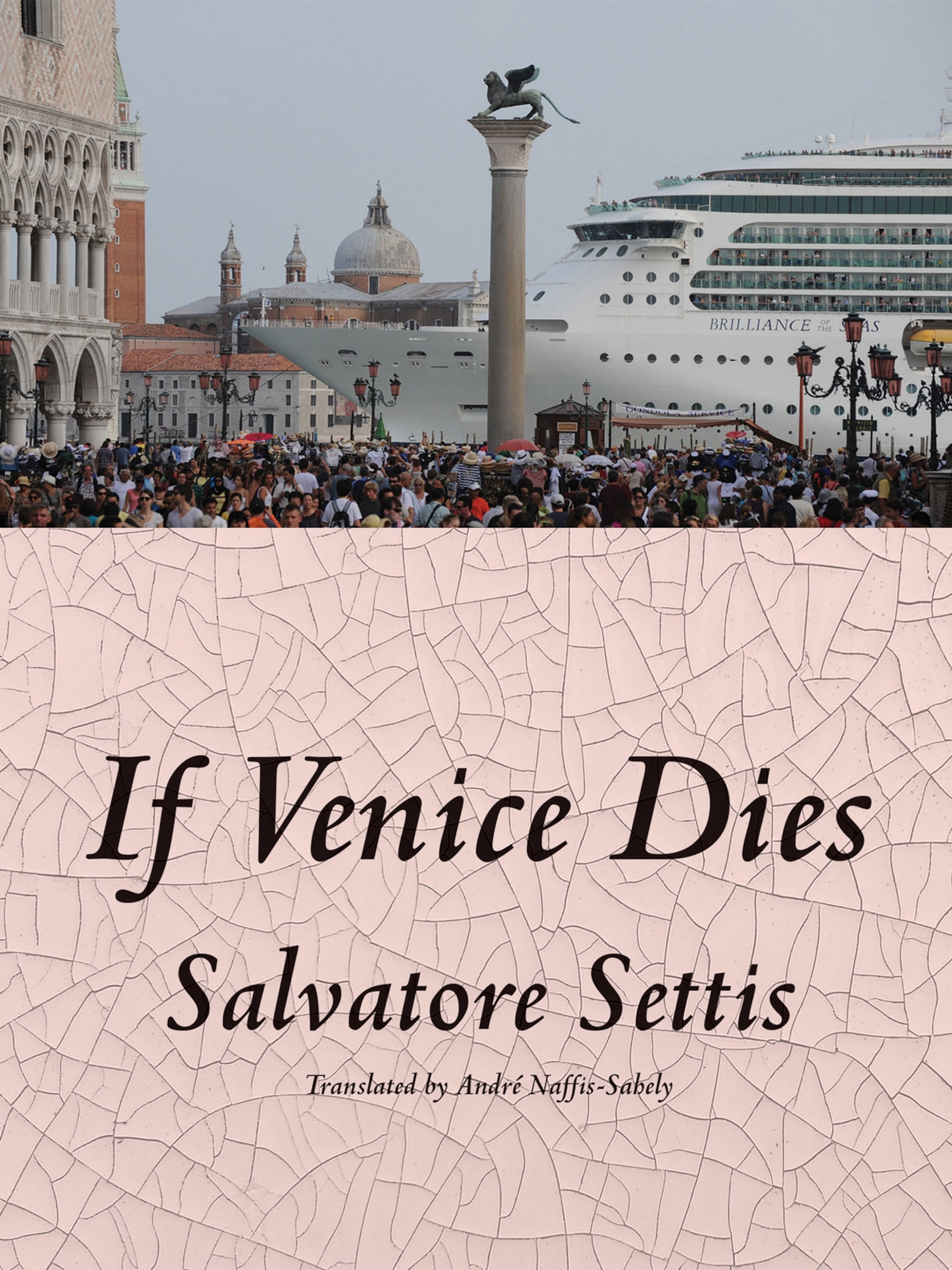

Floods were once the greatest threat to Venice. That danger has not receded, but the tsunami of tourists pouring into the city could cause greater harm, argues Salvatore Settis in his new book, If Venice Dies. Venetians are being driven out of the city by skyrocketing rent while giant cruise ships dwarf the skyline, risking a disaster like the Costa Concordia, the boat that sank off the Tuscan coast. There’s even talk of building a Venice theme park just outside the city. (Find out what it’s like to live in Venice.)

Speaking from his home in Pisa, Settis, an internationally renowned art historian, explains why saving Venice is not just important for Venetians but for all humanity, how the city inspired a new vision for Manhattan in the 1920s, and how corruption has blighted a major flood-control scheme.

Most of us who have seen Venice have gone there as tourists. According to you, we are part of a “plague” that is destroying the city. Should we stay away?

The fact that many tourists are willing to go to Venice is in itself a good thing. I am against any system whereby the number of entry tickets to the city is limited. The minute you would have to pay to enter the city if you are not a citizen, Venice would already have been turned into a theme park. That is precisely what I don’t want to happen.

But Venice cannot be a city that lives only from tourism. The reason Venice had its glory is because the city and Venetians were able to develop over centuries a number of productive activities. Why can’t we promote the same thing in Venice today? Approximately 2.6 citizens abandon the city every day. Venice now has 54,000 inhabitants, which represents a loss of 120,000 people in the last 50 years.

Meanwhile, the cost of living in Venice is increasing every day. Young people cannot afford to buy or rent an apartment in Venice, so they are moving to neighboring places. In Switzerland, where I taught for some years, federal law mandates that in every city, even the smallest village, you cannot have more than 20 percent of [houses owned as] second homes. The reason why the Swiss government decided to do this is precisely not to encourage this loss of local identity. If the citizens abandon Venice and it becomes only a tourist location, it will lose its soul.

You describe several ways in which cities can die. Give us a brief summary and explain how Venice is threatened by what you call “self-oblivion.”

First, when an enemy destroys them, like Carthage, or when foreign invaders colonize violently, as happened with the conquistadores in Mexico or Peru. But the most dreadful danger for a city now is loss of memory. By loss of memory, I mean not forgetting that we exist, but who we are.

Long before Venice, an example is Athens, the most glorious city in classical Greece. It completely lost its memory and even its name. In the Middle Ages nobody knew where Athens was because the name of the city got totally lost. It was called Setines, or Satine, which was a barbarized form of the name. In Athens, there was no culture or memory of the city’s past glories. Sometimes visitors from Byzantium would travel to Athens and ask, “Where is the place where Socrates used to teach? Where is the place where Aristotle used to teach?” Nobody could answer them.

An extreme example of this kind of oblivion regarding modern Venice is a project that was made public several years ago, of telling the history of Venice with a theme park, like Plymouth in the U.S., on an island in the lagoon. But Venice is able to tell its own history. We have no need to create a fake Doge’s Palace in order to tell the history of Venice. We have the real Doge’s Palace!

You say, “We the living should nurture beauty on a daily basis.” Why is beauty important to the human condition?

Beauty is a relative concept. What is beautiful for you may not be beautiful for me, and vice versa. I don’t mean an abstract beauty, something that belongs to a paradise of archetypes, but rather something that is rooted in reality. The kind of beauty we enjoy when visiting Venice or historic cities in Spain or Mexico is not just what we experience as the harmony of architecture and landscape, but the knowledge that these aggregations of buildings have been preserved over generations and generations. It’s the accumulation of experience, not just the aesthetic harmony.

You reserve your most colorful invective for the “skyscraper cruise ships” that now regularly dock in Venice. Why do they pose such a threat to the city?

The Costa Concordia shipwreck was one of the most unfortunate events in recent Italian history. It happened in Tuscany but it could have happened in Venice. One reason I am against these gigantic cruise ships docking in Venice is that they crowd the lagoon so close to Venice’s most famous historical monuments that sooner or later they may permanently damage the city’s history. They already disturb the aesthetic harmony of the city. Some cruise ships are twice as high as the Doge’s Palace and twice as long as St. Mark’s Square. If you are in Venice when one of those gigantic ships docks, it’s horrible to look at.

The lagoon itself has also been seriously polluted by the enormous amount of effluent discharged from these ships. After the Costa Concordia event, the Italian government decided to limit the distance cruise ships can be from our coast to three miles—with only one exception, which is Venice, where they can be one meter from the coast. This is a scandal!

You write, “Venice still lies within its watery walls.” Explain the relationship of the city to the lagoon and the sea beyond, and how this balance is under threat.

Venice is probably the only city of some importance without walls. Walls were not needed because there was the lagoon. That was the secret to its defense in medieval and Renaissance Europe. There’s a wonderful inscription from the early 16th century saying, “The lagoon is for Venice what walls are for other cities.”

But the lagoon is not simply some water around Venice. It’s a living environment where there are numerous birds, plants, and fish, whose existence is connected to the life of the lagoon itself. Historically, many islets in the lagoon, which are now abandoned, were used as hospitals, monasteries, and cemeteries or for the cultivation of different plants and vegetables. The city always interacted with the lagoon. Now this idea of considering the lagoon as very much part of the city is getting lost. This is one of the things Venetians risk forgetting.

There are 28 Venices in the United States and numerous other partial copies from Dubai to Chongqing, China. Describe how the city has been replicated across the world—and how this affects our view of the real Venice.

Probably no other city in the world has been replicated so many times. And Venice’s worldwide reputation means that the real Venice is particularly attractive. There are a number of cities called the Venice of the north, such as Stockholm. But nobody would ever say that Venice is the Stockholm of the south. [Laughs] Venice lost its political and commercial importance a long time ago with Napoleon’s invasion. But its centrality to the cultural imagination is still there.

What triggered this obsession with Venice and copying individual monuments was the collapse of the Campanile [Bell Tower] in St. Mark’s Square in 1902 due to an earthquake. After the bell tower was reconstructed with the same dimensions, in the same place, a number of copies were built all around the world. One of the best known is at the former railway station in Toronto. In the same period, Venice, California, was founded as a stylized copy of Venice.

This presence of Venice in the historical imagination should itself be a further argument to protect the real Venice. Whatever these different copies, whether in Las Vegas or even China, do to imitate Venice, they will never be able to copy the entire city because it’s too difficult to be copied. There’s no copy anywhere in the world of the Basilica of St. Mark’s. Why? Because it is too complex to be copied!

I was particularly interested in how Venice influenced the urban planning of New York. Explain how La Serenissima inspired the Big Apple.

This was something I didn’t know myself until I read a wonderful book by Rem Koolhaas on Manhattan. When the future of Manhattan was being discussed in the 1920s, a number of people had the idea that the best possible model for Manhattan was Venice. In 1924, New York City architect Harvey Corbett proposed separating vehicular and pedestrian traffic with arcaded sidewalks in order to create [reads] “a modernized Venice, a city of arcades, piazzas and bridges, with canals for streets, only the canals will not be filled with water but with freely flowing motor traffic.” This vision of Manhattan was not actually implemented, as we all know, but the initial concept was inspired by Venice as a model of the most beautiful city.

You are extremely critical of Venice’s local authorities, who you accuse of everything from incompetence to corruption. Talk about the MOSE project.

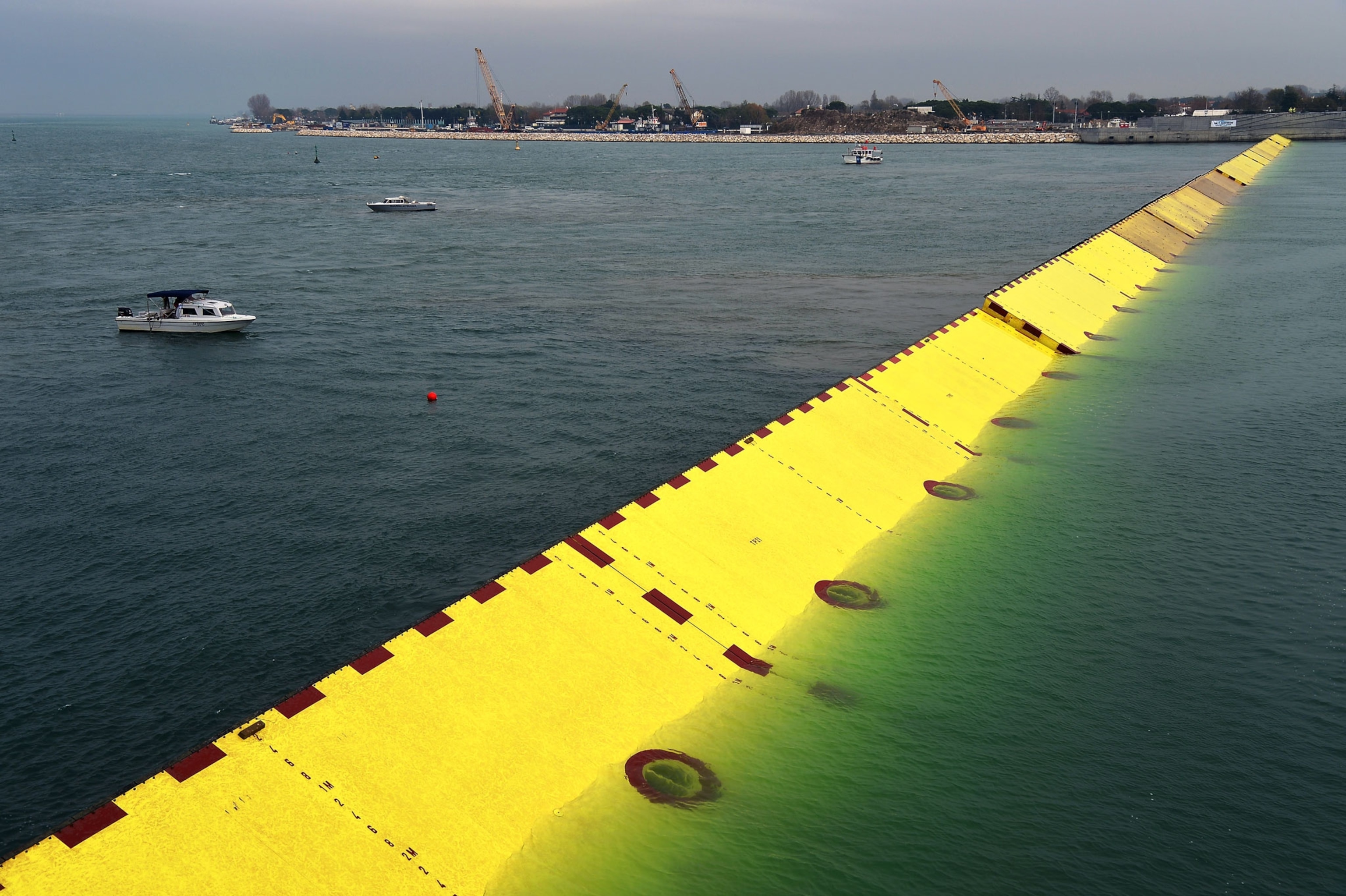

I am not the one who accused the local authorities of corruption. I am only quoting newspapers and books written about the subject. MOSE (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico) is an acronym for a system of barrages meant to protect the city and lagoon from what is called in Italian acqua alta, when the water is too high and risks invading the city. It already happens from time to time but could happen at a much more dramatic level.

I cannot dwell on the technical details. I can only say that this project has been approved, implemented, and financed by the Italian government. They are still working on it, though it’s far from sure that it will work, based as it is on technology that is more than 30 years old. In the meantime, Italian magistrates discovered that while the initial cost has been predicted at something like two billion euros, more than 6.5 billion have now been spent, at least two billion of which was spent on corruption.

The former president of the Veneto region, Giancarlo Galan, who later became a minister in Berlusconi’s government, has been arrested and put in jail. The former mayor of Venice, Giorgio Orsoni, who belonged to the same Democratic Party as the current prime minister, Matteo Renzi, has also been arrested and forced to resign. This major incidence of corruption in Venice shows how the real problems of the city—and the acqua alta is a real problem—are sometimes taken as an excuse for spending an enormous amount of public money, which is then siphoned off by corrupt people and organizations.

At the end of your book you call for a “new citizenship pact” to help protect Venice. Unpack that idea for us—and why it is so important that Venice doesn’t die.

First of all, for its own sake it’s important that Venice doesn’t die. It’s too important to let it die. Venice should be preserved not just for Venetians but for all humanity—that’s a very critical point. Venice is the paragon of historic cities and the clearest example in the world of how a city might be lost. In the future, if we don’t want to see a uniform image of cities, based on horizontal expansion and the vertical proliferation of skyscrapers, keeping some historic cities in their original shape is critically important. Nothing can give to the young generations 200 years from now an idea of the historic world better than a city that has fully preserved its historical shape. Preserving Venice as a historical city is important for Venetians. But it is equally, and perhaps even more important, for the world.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.