Why ancient Egyptians needed the flooding of the Nile

The inundation of water was more than just provision for crops and fields: the Egyptians called the event the coming of Hapy, god of abundance and fertility.

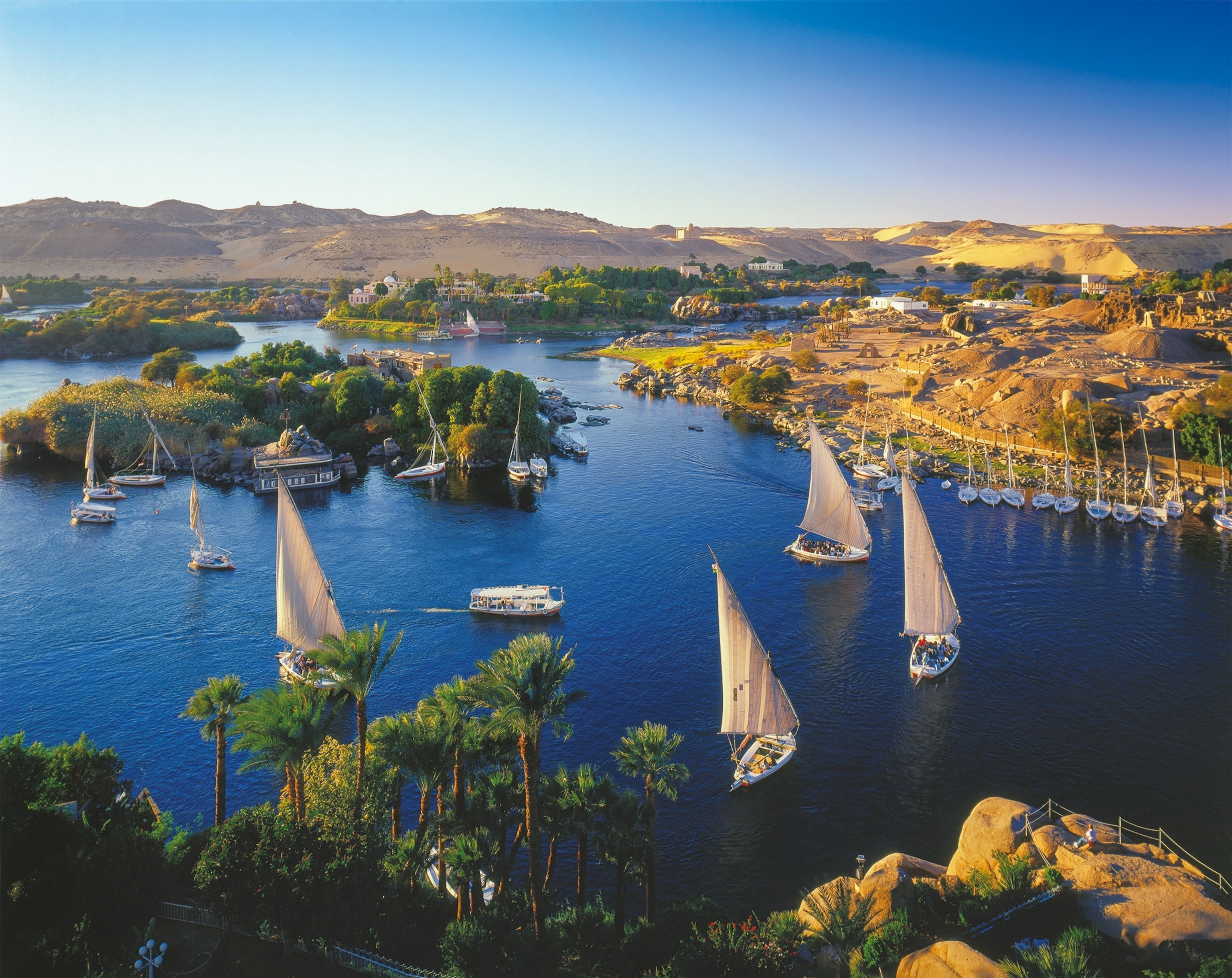

When Greek historian Herodotus visited Egypt around 450 B.C., he marveled at the country’s extraordinary natural wealth, famously writing, “Egypt is the gift of the Nile.” His words could not have been more accurate. Cities and settlements flourished along the banks of this great river that runs through a fertile valley. Without the life-giving waters of the Nile, Egypt would be nothing but desert.

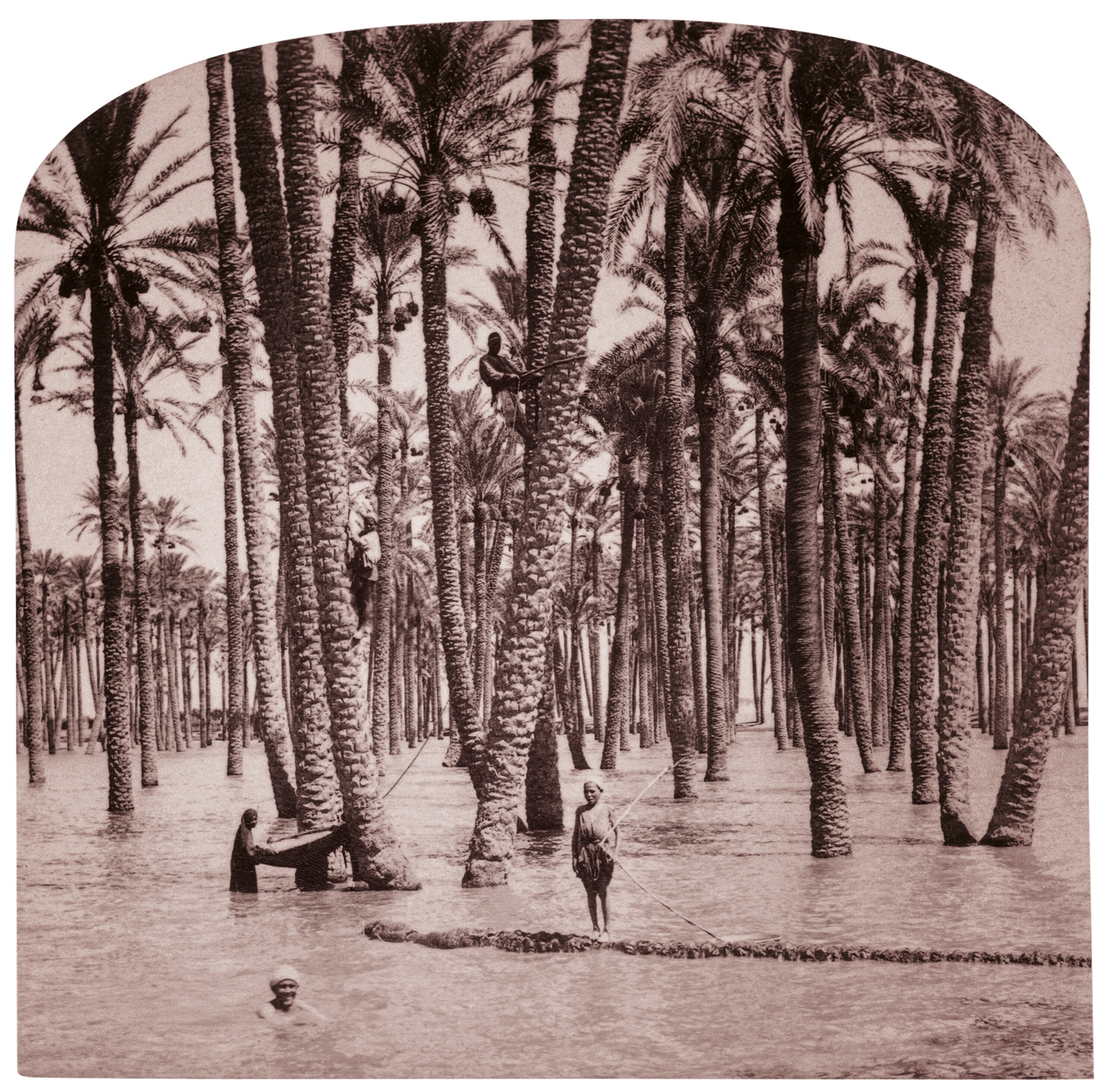

In pharaonic times, Egypt was known as Kemet, meaning “black land,” a reference to the dark, fertile silt deposited each year by the Nile’s flood. This natural fertilizer nourished the land and made it possible to grow crops, supporting a dense population and prosperous cities. The flood was an annual summertime occurrence, an event both anxiously awaited and deeply revered. The amount of water and nutrient-rich sediment left by the river determined the success of the year’s crops and whether Egyptians would feast or starve.

Lacking a scientific explanation for the phenomenon, the ancient Egyptians turned to mythology to explain it. They attributed the river’s rise to the god Hapy, whose yearly arrival was celebrated as the coming of Hapy. Over time, Hapy became the divine embodiment of the Nile’s yield and a symbol of fertility, prosperity, and life itself.

(How were the Pyramids of Giza built?)

Hapy: The spirit of the Nile

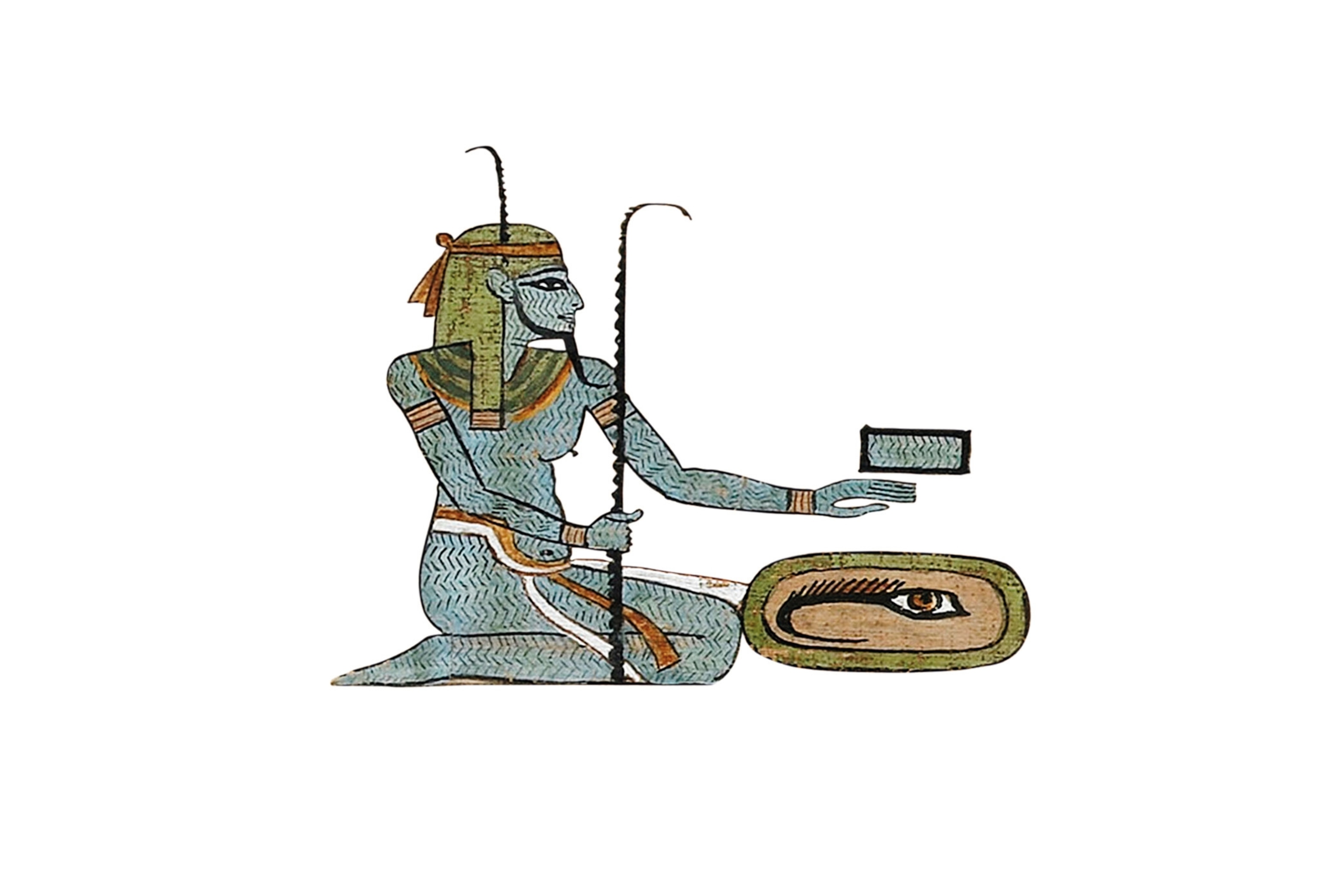

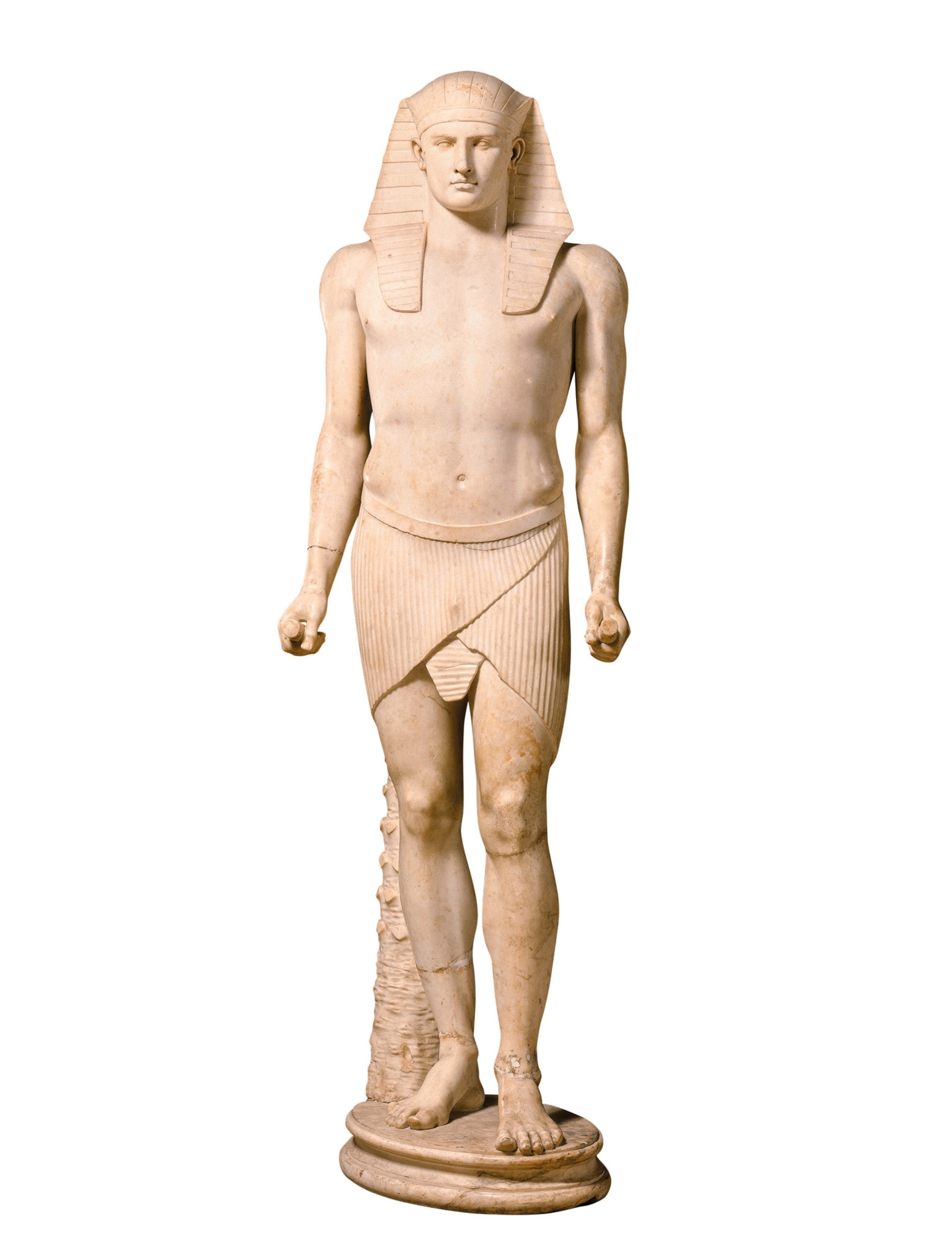

Depictions of Hapy reflected his deep association with the Nile’s life-giving powers. He was shown bearing both male and female traits: a braided beard, prominent breasts, and a rounded belly, the latter two symbolizing nourishment and abundance. His skin was often blue or green, alluding to the colors of the Nile’s water and vegetation.

Healing or harmful waters?

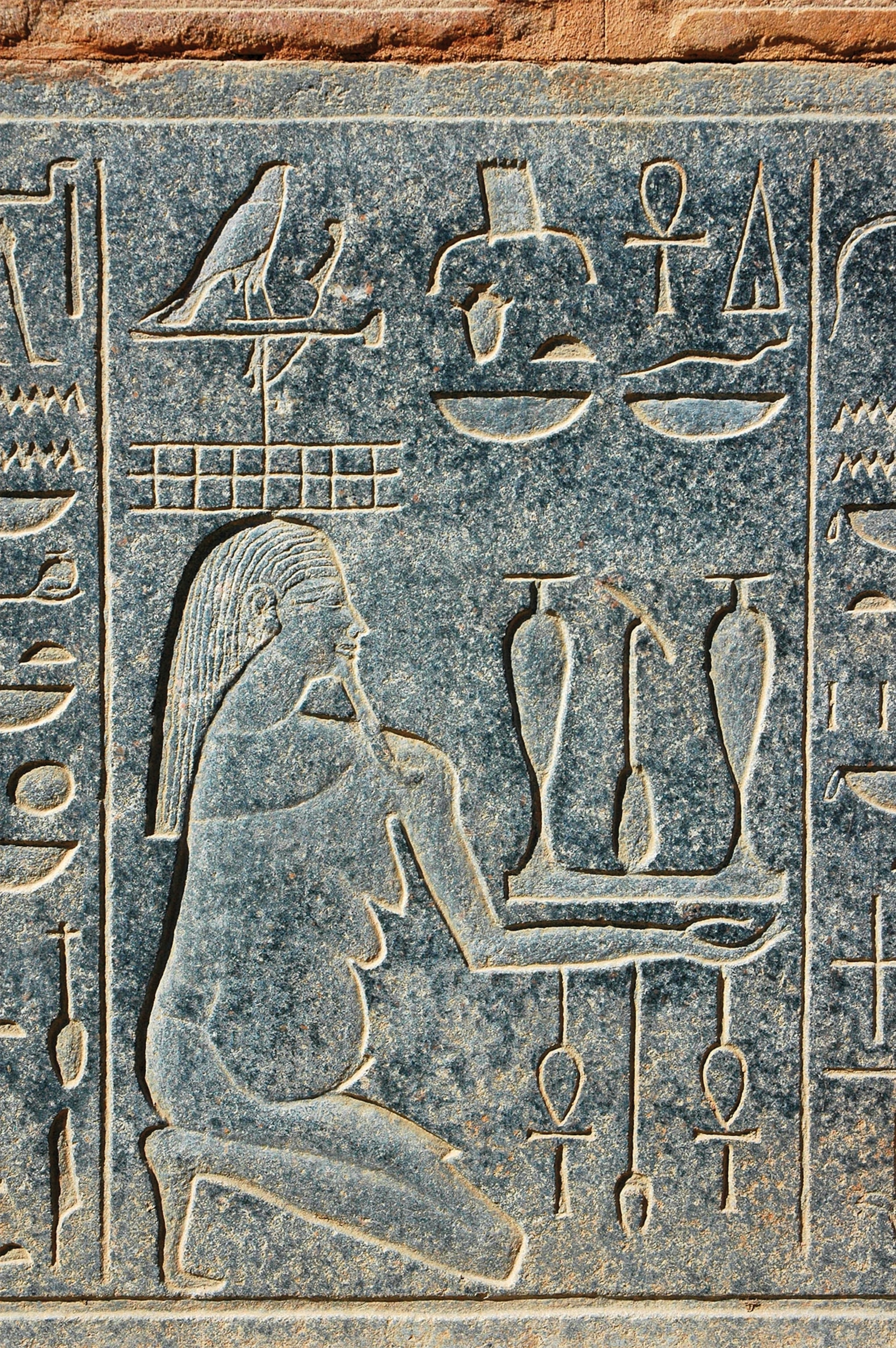

Hapy was commonly portrayed kneeling, holding a tray full of offerings—fruits, grains, fish, and other harvests made possible by the flood. Sometimes, he could be seen carrying a notched palm branch, a symbol of time and eternity also linked to the god Heh, who personified infinity. Most distinctively, Hapy wore a headdress featuring Egypt’s heraldic plants: the lotus (or lily) and the papyrus, symbolizing his dominion over Upper and Lower Egypt, respectively.

Duality played a central role in ancient Egyptian beliefs, and Hapy embodied this concept. He was often divided into twin divinities: Hap-Meht, the god of the northern Nile, wearing a papyrus linked to Lower Egypt and consort of the cobra goddess Wadjet; and Hap-Reset of the southern Nile, wearing a lotus and associated with Upper Egypt and the vulture goddess Nekhbet. Hapy could also be shown with two geese or holding two vessels,symbols of the river’s twin tributaries and the political unity of the two lands.

As the god of the flood, Hapy presided over the akhet season, when the Nile overflowed and spread its gifts across the land. This annual renewal was beautifully captured in the “Hymn to Hapy,” an anonymous work composed during the Middle Kingdom, which praised the god’s benevolent force: “When he rises, then the land is in joy; then every belly is glad.”

A god without temples

Despite being hailed as the father of the gods, there’s no evidence that Hapy had any temples dedicated solely to him. Instead, he was worshipped in sacred stretches of the river, particularly where its flow was turbulent, such as Gebel el Silsila, north of Aswan. Here, offerings were tossed into the rising waters annually.

Yet the flood was not without risks. An overly powerful inundation could wipe out villages; a weak one might trigger drought and famine. The “Hymn to Hapy” also revealed these perils: “When he delays, then noses are blocked, everyone is orphaned ... a million men perish among mankind.”

The stakes were high, and appeasing Hapy was an important duty. Egyptian kings often emphasized their role in gaining his favor in their texts, such as the “Instruction of Amenemhet,” written for the pharaoh’s son: “Hapy gave me honor on every field, so that none hungered during my years, none thirsted therein.”

(7 priceless artifacts you won't find at the new Grand Egyptian Museum)

The mystical source

Ancient Egyptians believed Hapy’s dwelling was located at the Nile’s mysterious source, thought to be hidden in Upper Egypt. Ancient texts indicate that the river rose between two mythical mountains, Qer-Hapy (Cave of Hapy) and Mu-Hapy (Water of Hapy), near the islands of Philae and Elephantine.

In the second century A.D. Ptolemy, a geographer from Roman Alexandria, suggested that the Nile’s source lay far to the south, in two large lakes situated near the Lunae Montes (Mountains of the Moon), a mythical range he placed in central Africa. These lakes, he believed, fed the Nile through a series of tributaries. Although Ptolemy’s maps were based on hearsay from merchants, travelers, and other geographers, he came surprisingly close: The Mountains of the Moon may correspond to the Rwenzori Mountains, located between modern-day Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, near Lake Edward and Lake Albert. In reality, the Nile has multiple sources, including three main tributaries: the Blue Nile, the White Nile, and the Atbara. Yet Ptolemy’s ideas remained prevalent for thousands of years.

Another widespread belief was that Hapy dwelled in a cave near the First Cataract at Aswan, from where he poured out the waters of the Nun, the primeval ocean, thereby causing the annual flood. The First Cataract is where the Nile’s floodwaters emerge and spill over granite boulders, marking the natural border between Egypt and Nubia. This legendary cave, sometimes called the Cave of Hapy, was believed to lie beneath or near Elephantine Island, a site long associated with the river’s divine source.

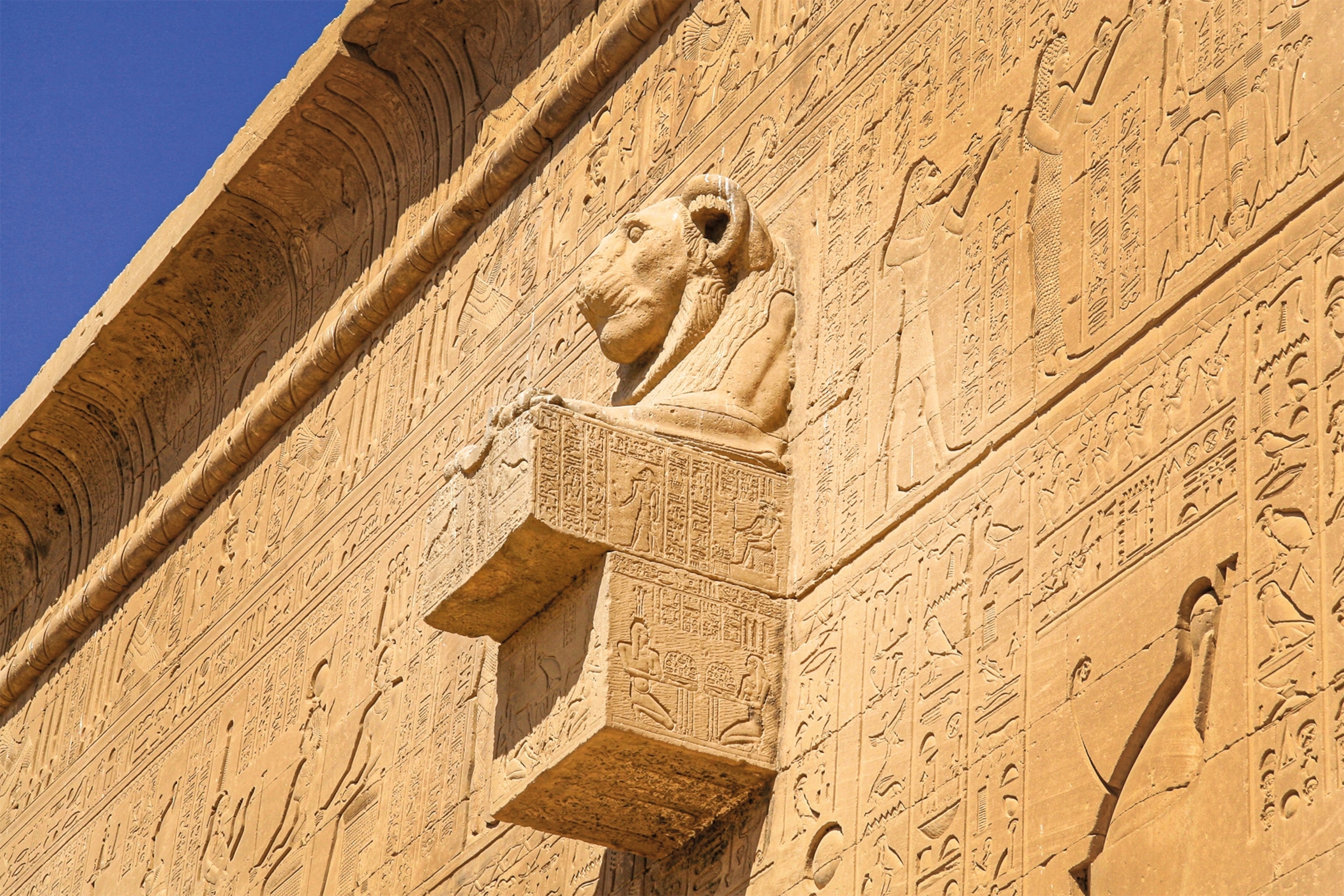

Ancient texts and inscriptions describe the cave as the mystical wellspring of the Nile’s floodwaters. The Famine Stela carved on nearby Sehel Island during the Ptolemaic period reads: “It is the house of sleep of Hapy ... he brings the flood: bounding up he copulates, as man copulates with woman.” In some representations, Hapy can be seen emerging from the grotto accompanied by crocodiles and guarded by serpents—symbols of divine power and chaos. A relief from the Gate of Hadrian at the Temple of Isis shows Hapy in a cave protected by a serpent.

Drowning and deification

Pharaohs and the power of the flood

Maintaining the delicate balance of nature fell to the pharaoh, seen as the guarantor of maat— the Egyptian concept of cosmic order, justice, and harmony. Pharaoh Djoser, featured in the Famine Stela, expresses deep anguish during a seven-year drought:

You May Also Like

I was in mourning on my throne. Those of the palace were in grief. My heart was in great affliction, Because Hapy had failed to come in time in a period of seven years. Grain was scant, Kernels were dried up, Scarce was every kind of food.

On the sides of many thrones, instead of the usual dynastic gods Horus and Seth, two figures of Hapy can be seen raising the lotus and papyrus plants. These entwined stems—symbolizing Upper and Lower Egypt—cross a windpipe and lungs, forming the sema-tawy, or “the union of the Two Lands.” It is a powerful symbol, rippling with the belief that Egypt’s prosperity, balance, and enduring unity flow from the strength and favor of the Nile god.