Even Remote Coral Reefs Aren't Spared From Devastation

A combination of climate change, cyclones, and human activity has led to intense die-offs around the Samoan island of Upolu.

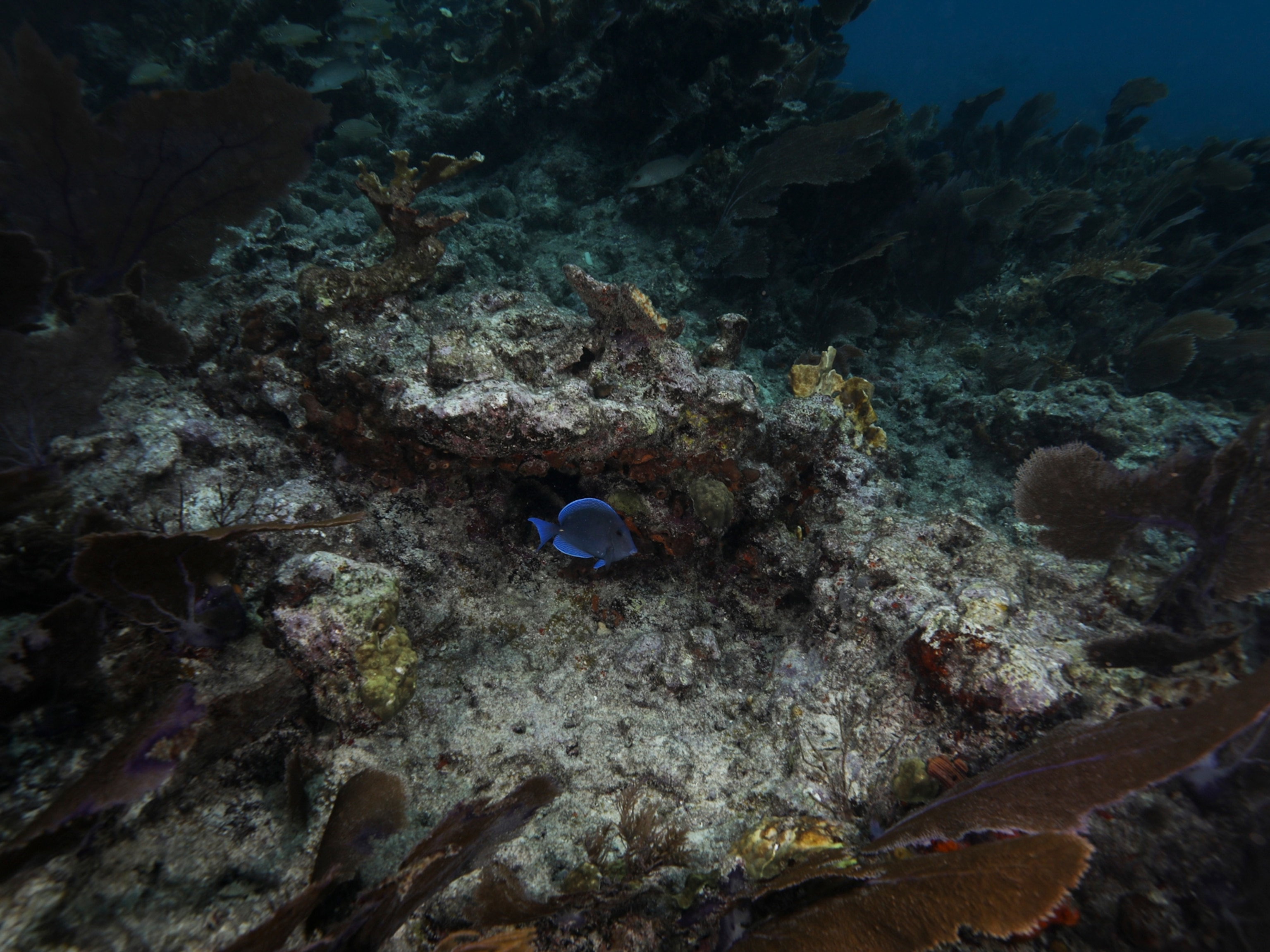

Coral reefs are in grave danger. Around the world, including at well-known sites like the Great Barrier Reef, the colonies of carbonaceous creatures have faced dramatic losses spurred by climate change, rapidly warming waters, and human activities such as overfishing and water pollution.

Starting in 2016, a team of researchers sponsored by the Tara Expeditions Foundation set out to study the remote reefs surrounding Samoa’s most populous island, Upolu, in the South Pacific Ocean, about 2,600 miles southwest of Hawaii. They thought that its location away from large urban centers and human-made stressors might mean the coral had been spared from some of the same devastating effects. (See How Scientists Are Trying to Save Reefs Using "Floating Sunscreen.")

Unfortunately, they found more of the same.

In a study published in April in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin, the team reports similar scenes of dead and dying coral from their surveys of 124 reef sites.

In half the sites surveyed, live corals populated less than one percent of a given reef. At 80 percent of the Samoan sites, live corals were below 10 percent. The scientists estimate that these reefs may have previously had live coverage between 60 and 80 percent, and graveyards of recently deceased coral suggest that much of the die-off happened in the recent past.

Additionally, fish from two species found in the reefs were 10 percent smaller than individuals of the same species around nearby islands, and they were found in schools of smaller numbers.

The researchers think a combination of physical damage from tropical cyclones, climate change, and local activity have all played a role in the coral's dire situation. (Find out how the window to save the world's coral reefs is closing rapidly.)

Upolu has been repeatedly struck by tropical cyclones and even tsunamis in the past few years, which can cause physical damage to coral. Torrential rains from cyclones and other strong storms wash sediment and pollutants from the land into the ocean, further stressing the coral and making them more susceptible to the effects of warming waters. And even on a remote island like Upolu, that effect can be exacerbated by soil erosion from agriculture and clear-cut forests.

In addition, overfishing along the reefs disrupts their delicate ecological balance, thinning the numbers of fish that help coral grow by eating up algae and turf that occupy the same seafloor.

Despite all this, the team did find one glimmer of hope—two sites that sit within marine protected areas were found with much higher live coral coverage, a sign that with proper management and care, it’s possible to help the stressed out reefs survive.