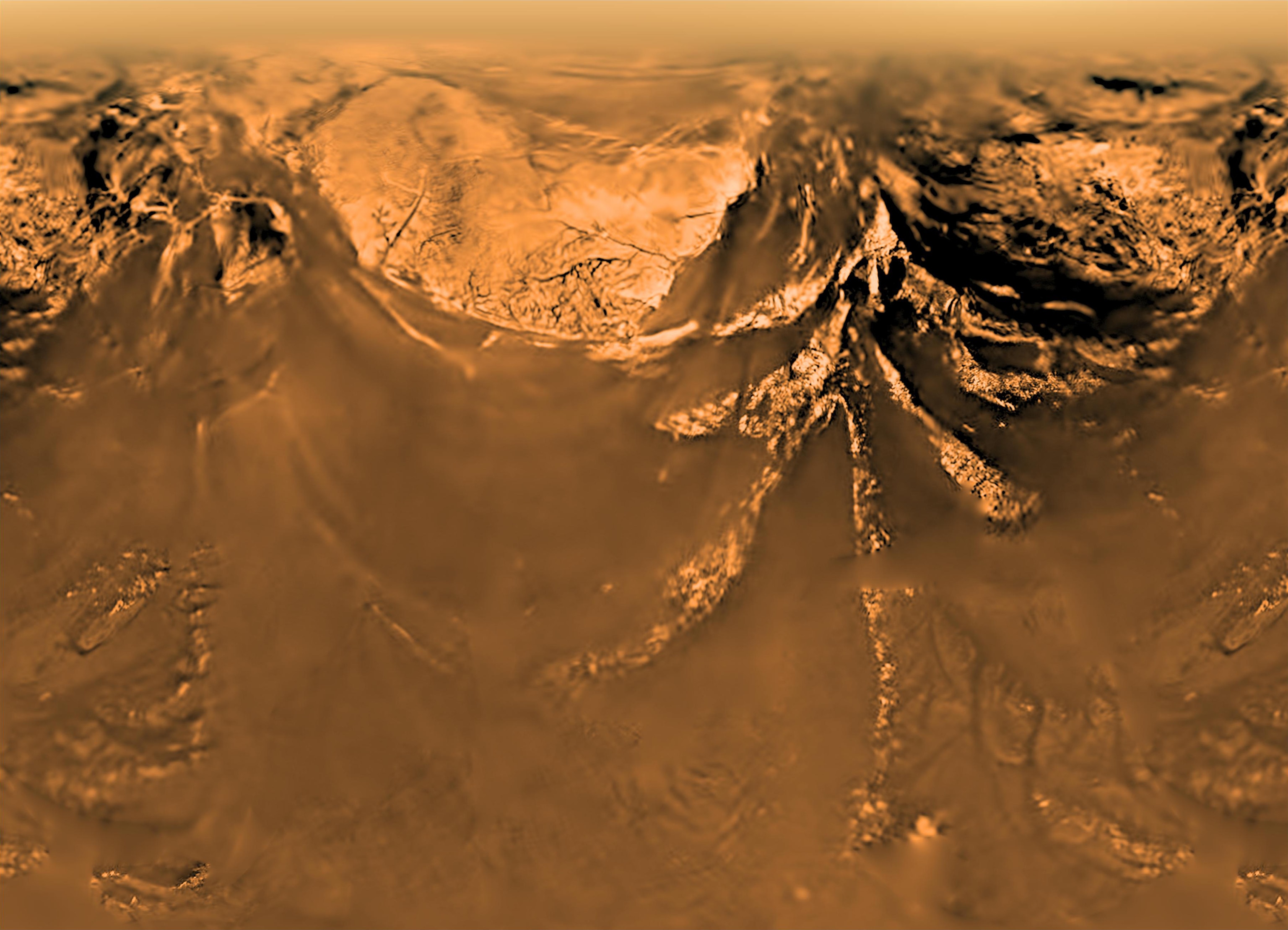

NASA Gets Last Close Look at This Eerie Alien Moon

After a poignant farewell flyby of Saturn’s largest moon, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is on a collision course with the ringed planet itself.

On April 21, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft paid its final visit to Saturn’s largest moon, swooping roughly 600 miles above Titan’s haze-wrapped surface.

This last hurrah, the 127th time Cassini flew by Titan, forms what scientists hope will be an intermediate bookend to the exploration of the alien world—a realm that really started to come into focus 12 years ago when a small spacecraft parachuted through the moon’s thick, extraterrestrial haze and drifted down toward its surface.

During its descent and brief moments among the rock-hard icy pebbles strewn over the ground, the probe gathered enough data to give scientists a glimpse of a moon that looks deceptively Earth-like.

Nearly 900 million miles from the sun, temperatures on Titan are so low that ice is as hard as rock and organic compounds like ethane and methane—which are normally gases on Earth—are chilled into slick liquids that pool and flow into enormous lakes and seas.

With its mountains, rain, winds, and waves, 3,200-mile-wide Titan is really more like a planet than just another dead, cratered moon. It not only has those oily seas on its surface, but it also harbors a buried ocean of liquid water, making it among the best places to search for life beyond Earth.

Beneath that tangerine shroud hides a world where extraterrestrial lifeforms could thrive—whether they use chemistries similar to our own or completely alien metabolic engines.

“Titan is kind of a double ocean world,” says planetary scientist Sarah Hörst of the Johns Hopkins University. “In principle, there’s the possibility that it has both life as we know it and life as we don’t know it.”

During its final flyby, Cassini focused on the lakes and seas sprinkled near Titan’s north pole, sending data back to Earth that will help scientists plumb those dark, oily depths—and maybe even solve the mystery of ephemeral features known colloquially as Titan’s “magic islands.”

PIERCING THE HAZE

After decades of wondering what lay beneath that puffy, opaque atmosphere, scientists got their first good glimpse of Titan on January 14, 2005, when the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe became the first robotic explorer to touch the surface of this smoggy moon and beam back detailed pictures.

The Huygens probe hitchhiked to the Saturn system on board Cassini, which dropped off the lander not long after pulling into orbit around the ringed planet.

Though Cassini had been assigned the task of exploring Saturn and its many moons, that little probe—named after the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens—had just one target in sight: Titan, shrouded in a frustratingly puffy atmosphere that mostly obscures the moon’s surface.

After a 20-day journey to Titan, Huygens sank through the moon's atmosphere for more than two hours.

The spacecraft punched a hole in the icy ground, bounced, slid, and wobbled. After a few seconds, it came to rest in a damp floodplain where temperatures were nearly 300 degrees below zero. There, Huygens frantically gathered data for about an hour before its batteries died and its mothership disappeared over the horizon.

“Huygens revealed Titan’s environment directly, whereas most of what was 'known' before was rather indirectly determined,” says the University of Arizona’s Ralph Lorenz. “It showed us the surface close up.”

Data showed us highlands, ravines, and channels carved by liquids, as well as winds whipping through Titan’s nitrogen atmosphere. Measurements from the surface showed the probe didn’t land in a dry desert, and that some kind of liquid was moistening the sand beneath it.

Huygens’ atmospheric measurements have since helped scientists reconstruct the composition of Titan’s ancient atmosphere (probably a combination of ammonia and methane) and study how organic molecules can behave in a predominantly nitrogen atmosphere, as Earth’s once was before life evolved and oxygen became abundant.

“It’s the only other substantial nitrogen atmosphere besides ours,” Hörst says. “Presumably, a lot of the chemistry in Titan’s atmosphere could have been happening on the early Earth, before oxygen.”

MIRROR MOON

The Huygens mission marks the first and—so far—last time humans set a spacecraft on a moon other than our own. And this last pass from Cassini marks the final planned reconnaissance of the mirror world, at least for the foreseeable future.

It didn’t have to be that way.

A mission called the Titan Mare Explorer was once among NASA’s top picks for a future interplanetary adventure. Had it been selected, that mission would have sent a space boat to explore Ligeia Mare, one of Titan’s largest northern seas. Made of runny, liquid hydrocarbons, the moon’s surface seas could be home to life with a completely different chemistry than ours.

“That’s a test for a diversity of life: Could you also find life that uses a different liquid than life on Earth?” Hörst says.

In a poignant twist of fate, Cassini’s closing handshake with Titan signals the start of its demise. During the encounter, the moon’s gravity helped put humanity’s ambassador to the Saturn system on a collision course with the ringed master itself: Later this year, Cassini’s mission will end with a dramatic plunge into Saturn, but not before it completes 22 daring dives between the giant and its rings.

Still, even after they’re gone, spacecraft like Huygens and Cassini can continue to offer new clues about our solar system and help scientists build the case for future missions, thanks to the wealth of data they sent home.

With Titan, we’ve found a world that is both totally alien and yet somewhat familiar. Seasonal rains darken its plains, it’s rich in organic molecules, and a wintry vortex decorates its poles (complete with hydrogen cyanide clouds).

“Titan's appeal is its mix of the familiar and exotic,” Lorenz says. “Ultra-low temperatures, ices, organics, liquid methane—but making familiar rain, rivers, dunes, seas.”

Simply put, it’s a world that scientists would dearly love to get to know a little bit better, not only because of the excitement of exploring extraterrestrial terrains, but because it can teach us more about this planet we call home.

“Titan is so active and has so many Earth-like processes, it’s such a good test for our fundamental understanding of how planets work,” Hörst says.