In the early morning hours of July 20 on Tanegashima, a small island just off the southern coast of Kyushu, Japan, a 174-foot rocket roared to life and lifted a spacecraft on the first leg of a 306-million-mile journey to Mars.

The spacecraft itself, however, is not Japanese. Called al-Amal, or “Hope,” it was designed and managed by the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) in the United Arab Emirates. Safely separated now from the Japanese rocket, the probe will fire its own thrusters to leave Earth orbit for Mars in about 28 days, arriving in February 2021 to complete the first interplanetary voyage initiated by an Arab country.

“It was an indescribable feeling,” Sarah al-Amiri, the UAE’s minister of advanced science and the Hope science lead, said after the launch. “This is the future of the UAE.”

Two other spacefaring nations are also taking advantage of a launch window this summer, when Earth and Mars are favorably aligned, that only occurs every 26 months. NASA’s next flagship rover, Perseverance, and the Chinese Tianwen-1 lander and small rover are scheduled to launch to Mars in the coming days, also arriving in early 2021.

The Hope orbiter was the first to depart, blasting off at 6:58 a.m. local time in Japan (5:58 p.m. EDT on July 19). Its primary mission will last 687 days—one year on Mars—studying the atmosphere and weather patterns of the planet.

But the mission also reflects a broader ambition in the UAE to drive innovation in science and technology and diversify the economy of the tiny but oil-rich nation. For Emirati scientists and political leaders, the mission represents a new chapter for a part of the world with a rich history of scientific discovery.

“We Arabs love to connect things to our heritage and the past, but Hope really means the future,” says Nidhal Guessoum, an astrophysicist and professor at the American University of Sharjah in the UAE. “Hope means that we turn away from the conflicts and focus on human and economic development.”

Arriving at Mars for the golden jubilee

The Emirates Mars Mission (EMM) was initiated in 2014 by the UAE prime minister, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum of Dubai. He directed the country’s space program, which launched its first satellite in 2009, to send a spacecraft to Mars ahead of the 50th anniversary of the UAE’s founding on December 2, 2021.

“Most people assume it is for prestige, but it’s actually not,” Guessoum says. By focusing on space exploration, he adds, Emirati leaders hope to inspire a new generation of young Arabs to pursue careers in the sciences, stimulating competition in a region beset by numerous challenges. “STEM becomes your top priority.”

The UAE comprises a federation of seven territories, or emirates, on the Persian Gulf. The country has sought to diversify its economy in recent years, as market shocks and global trends highlighted the vulnerability of oil-dependent Gulf nations—even before the coronavirus pandemic sent oil prices plummeting. Emirati leaders intend for the Hope probe to serve as a disruptive event, accelerating the country toward a knowledge-based economy that retains world-class researchers to work in scientific and technological fields.

The mission also carries great symbolism as the first interplanetary voyage undertaken by an Arab country. The legacy of the Islamic Golden Age—which began in the eighth century and saw Arab and Muslim scientists make great strides in fields such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy—still holds great emotional power in a part of the world now beset by unemployment, extremism, displacement, civil wars, and poverty.

“We as a region used to generate knowledge," says Omar Sharaf, the Hope project director. “A lot of the technologies that we use today and the science being done today is based on the outcomes of scientists from the region, from different backgrounds, from different ethnic groups.”

The interplanetary flight to Mars could spur competition among countries in the Middle East and North Africa to further develop their own STEM industries, Sharaf says. And in an effort to draw from a wide pool of personnel throughout the region, the UAE recently launched a new program to recruit Arab researchers and train them in astronomy and planetary science. Mission leaders hope these efforts will inspire young people in Arab countries to practice science, countering the appeal of extremist groups and limiting brain drain as scientists emigrate to other parts of the world.

“How do you create, then, opportunities out of knowledge, which is the fuel of most economies around the world?” al-Amiri asks. “The heroes that we need to speak about are those that promote stability by doing things that have economic impact through creating jobs and opportunities for youth.”

Hope is the latest of several major advances made by the UAE space program. In 2018, Hazza al-Mansouri became the first Emirati to go into orbit, spending a little over a week on the International Space Station. He went on to deliver dozens of talks around the country, and the nation’s astronaut program, created in 2017, has announced the lofty goal of establishing a human base on Mars by 2117.

These rapid strides in space, including the launch in 2018 of the first Earth-observation satellite built entirely by Emirati engineers, are thanks in large part to a unique approach to international collaboration.

Interplanetary mentorship

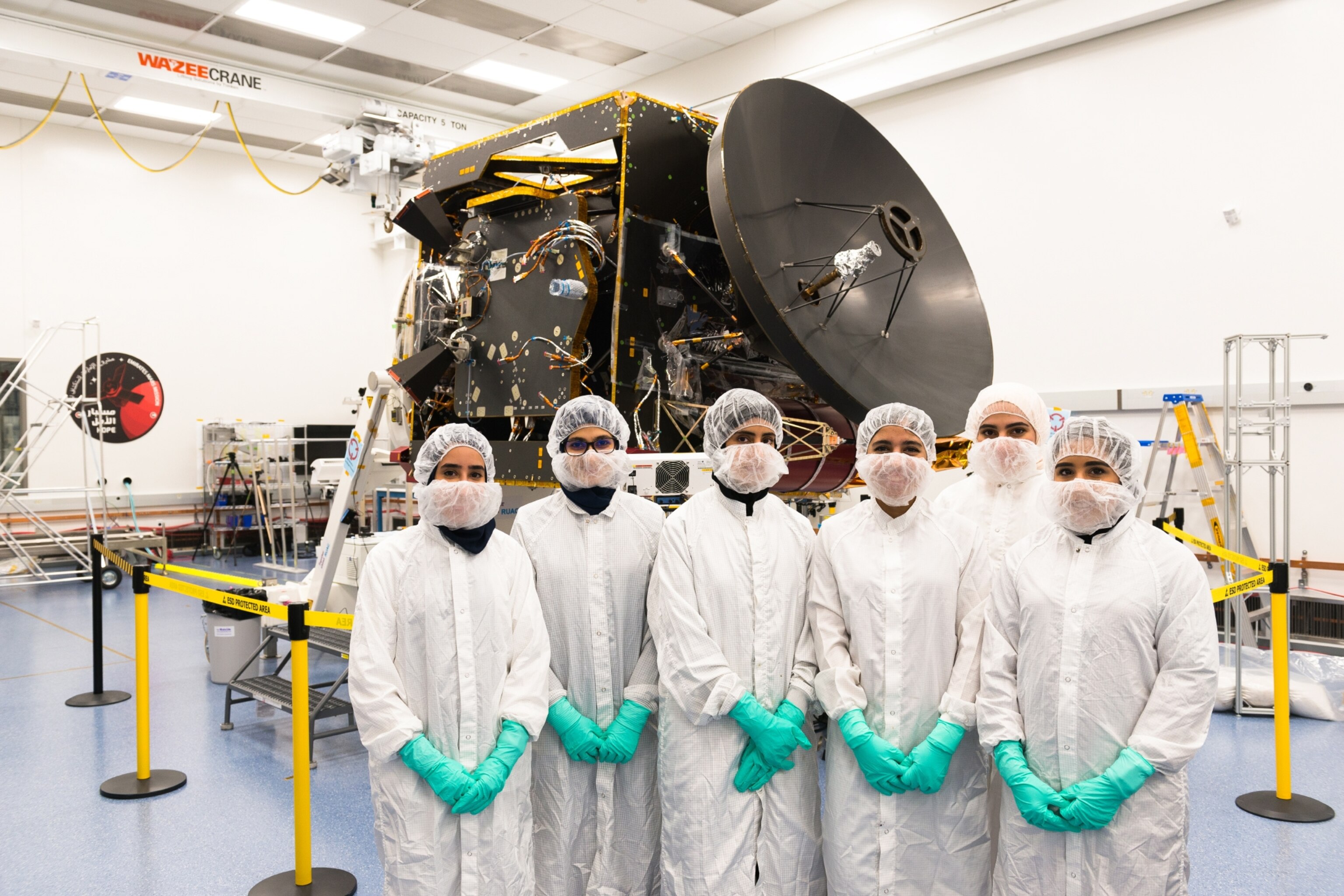

The Hope mission was designed to maximize the transfer of knowledge to the UAE’s young cadre of engineers and scientists—a team with an average age of 27. To this end, the country’s space program turned to the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado Boulder, which has a long history of building spacecraft and science instruments, as well as to Arizona State University and the University of California, Berkeley.

The arrangement, modeled on the UAE’s earlier work with South Korea on its first satellite, helped the Emirati scientists and technicians quickly develop expertise in Mars exploration.

“The Emiratis decided to do this the hard way,” says Pete Withnell, the program manager at LASP. “They wanted to be deeply involved at every level from the leadership to the engineer and everywhere in between.”

The six-year lead-up to launch also involved working with the global science community to develop a Mars science program “completely from scratch,” al-Amiri says. “We had to develop an entirely new division that was completely foreign to us, and that is space science.” The Hope science team is 80 percent women, she adds, a figure that reflects the high percentage of women in STEM programs among the UAE’s youth and in its universities.

“For us, it’s not odd nor is it something out of the norm,” al-Amiri says. “It’s based on merit.”

But the rapid run-up to launch in time for the UAE’s 50th anniversary nearly came to naught when the coronavirus pandemic shut down airports and slowed global industries to a crawl. “The mission was at risk,” Sharaf says.

He and his colleagues decided to accelerate the mission, sending advance teams to the launch site in Japan with enough lead time to spend two weeks in quarantine. The spacecraft was sent from Colorado to Dubai for final testing, then on to Nagoya airport in Japan, and finally arrived by barge at the Tanegashima Space Center.

A true Martian weather satellite

The Hope orbiter is scheduled to arrive at Mars in February, entering an elliptical orbit around the equator that takes it between 20,000 and 40,000 kilometers (12,500 and 25,000 miles) from the planet’s surface. Flying higher than previous Martian satellites, the mission will provide unique insights into the planet’s global climate patterns.

“The Martian climate system is quite complex,” says François Forget, a French astrophysicist and Mars expert who worked with the Hope science team. It has dust storms, for example, that can grow large enough to engulf the planet and block out the sun. Most of the planet’s thin atmosphere is carbon dioxide, and a substantial portion of it freezes each winter to form CO2 ice clouds and transient polar ice caps.

Most Mars orbiters fly around the poles, circling low enough to study the surface in detail but limiting their view of global weather patterns. Hope’s distant orbit around the equator will allow the craft to monitor the large-scale dynamics of the planet across all four seasons of the Martian year.

“We will see everything,” Forget says.

By studying interactions between the lower and upper atmospheres, and measuring the escape of hydrogen and oxygen into space, the mission will shed light on the longstanding mystery of how Mars lost much of its early atmosphere and liquid water, transforming from a potentially habitable planet to the barren world we see today. Its orbit will allow it to observe the same location continuously for up to 12 hours, offering a glimpse of real-time weather phenomena, such as the eruption of dust storms.

Detailed atmospheric models could also play a crucial role in future crewed missions to Mars, informing the selection of landing sites, strategies for survival on the surface, and insights into the planet’s water cycle. Being able to forecast dust storms could be particularly crucial to humans wanting to blast off from the Martian surface to return home.

But beyond discoveries about Mars, pushing into interplanetary space marks a scientific leap for the Arab world—and a return to old form.

“Everyone coexisted and people accepted differences,” Sharaf says of the period of cultural and scientific flourishing between the 8th and 14th centuries in the Middle East. “The moment we stopped accepting differences, we started moving backward.”

Sharaf hopes flying to Mars may be the spark that ignites the dreams of a new generation. “The mission is about creating future heroes,” he says.