Dawn Wall's Underdog Climber Recounts His Push to Catch Up

Kevin Jorgeson, lagging behind his partner, made an eight-foot leap of faith to finish the toughest part of his historic climb.

Editor's Note: Climbers Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson have completed their ascent of Yosemite's Dawn Wall. See photos of the moment they reached the top.

Kevin Jorgeson and Tommy Caldwell have been living on the side of El Capitan for the past 16 days, and everything about their appearance shows it. Their beards have grown thick. Their matted hair has taken on an unwashed sheen. And their physiques—already as lean and tough as strips of jerky—have grown gaunter and somehow wolfish.

Indeed, Caldwell and Jorgeson are like two hungry animals, stalking their prize as they ascend in the dead of night.

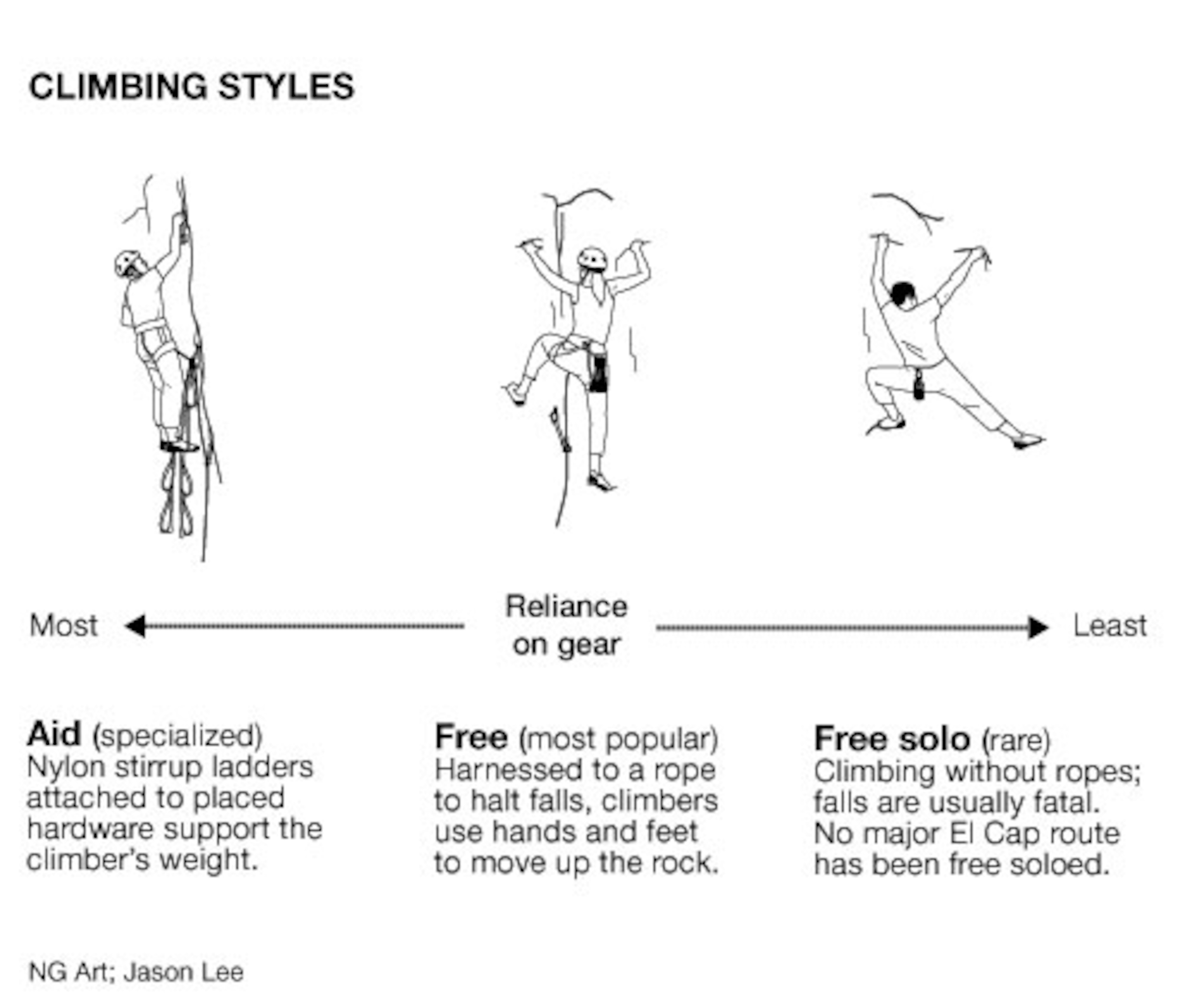

That prize is completing the historic first free ascent of the Dawn Wall of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, widely considered the most difficult "big wall" rock climb in the world. Free climbing means the pair must use their hands and feet to ascend the natural features presented by the rock, employing ropes and gear only to stop a fall.

The climbers wait until dusk or even night to climb, using headlamps to see. The rock needs to be cold to prevent their fingers and hands from perspiring too much and slipping off these imperceptibly tiny granite handholds. (See photos of Caldwell and Jorgenson making their historic climb on the Dawn Wall.)

Caldwell, 36, is the more accomplished and experienced climber of the two. The Dawn Wall will be his 12th free climb on El Capitan. For Jorgeson, 30, it will be the first.

This disparity in experience came into play over the past week as Caldwell went on an unstoppable tear. Each day he dispatched pitch after pitch—as climbers call a rope-length of climbing—completing all the way through pitch 20. In total, the Dawn Wall is about 3,000 feet (914 meters) tall, and breaks down into 32 pitches.

Now just 12 pitches of relatively easier climbing, a total of about a thousand feet, separate Caldwell from the summit. But instead of pressing on to the top, he has chosen to wait for his climbing partner to catch up, returning to support his climb as he continues to progress upward. (Read more about Caldwell's dilemma in "Climber on Historic Yosemite Attempt Faces Yet Another Fateful Choice.")

Pitches 12 through 20 constitute the hardest climbing on the Dawn Wall. Caldwell and Jorgeson have battled through this difficult stretch as the world looks on. They spend their nights in a portaledge camp—essentially a hanging platform tent—fixed to the wall near the middle of this block of pitches.

Their goal is to complete all 32 pitches in sequence, without returning to the ground. To consider themselves successful, they must also climb each pitch without falling for it to count as being "freed"—as in "free of aid."

Caldwell and Jorgeson can maneuver from pitch to pitch with a network of rigged ropes. They use mechanical ascenders to help them climb the rigged ropes to reach the pitch du jour. At the end of a climbing day, they descend the same ropes via rappel devices to their portaledge camp.

Their latest block of climbing is so demanding, Caldwell and Jorgeson have expected themselves to do only one pitch per day.

On January 1, both climbers succeeded on pitch 14, a breakthrough for both to conquer this first significant hurdle.

Then came pitch 15, equally difficult. Caldwell quickly "sent," which simply means climbing without falling. Jorgeson, however, did not.

Instead, Jorgeson stalled out on pitch 15. Over the next ten days, he made attempt after attempt, each time failing at one section that contained the "two sharpest, smallest holds on the route," according to Caldwell.

One of the biggest issues for Jorgeson was tears in his fingertip skin. For a climber, a skin tear on such finger-intensive rock climbing is akin to a flat tire for someone trying to win a stage in the Tour de France.

Over the week, Jorgeson sought advice from the climbing world about how best to tape his fingertips. He experimented with various methods, only to encounter profound frustration when he'd reach those two sharp, tiny holds on pitch 15, where he'd have his tape slip and cause him to fall.

Over the week, success appeared to grow only more elusive for Jorgeson. The pressure was on, and he was painfully aware that he was holding his partner back. If he didn't do pitch 15 soon, Caldwell would have to decide whether to move on alone.

On Friday, January 9, Jorgeson broke through. After two days of rest to let his skin heal, and having perfected his taping system, Jorgeson climbed pitch 15 without falling. He called the experience "surreal."

The success reenergized the team in a major way, as Jorgeson seemed to be catching a second wind. By Saturday, Jorgeson had also completed pitches 16 and 17—another major breakthrough.

Jorgeson has now completed all the pitches with the most difficult ratings on the Dawn Wall. He stands just three pitches away from matching Caldwell's high point. But those three pitches, still extremely difficult, remain big question marks for Jorgeson.

Speaking to National Geographic from his portaledge just after waking up, Jorgeson shares the details behind his latest progress.

Congrats on completing pitches 15, 16, and 17—especially pitch 15. What was it like to break through on a pitch that had thwarted you for the last ten days?

Thank you! It was so crazy. It was surreal. It was actually a scientific breakthrough, if you will. I asked Kyle Berkompas to render me a video of all my attempts on pitch 15 so that I could analyze it.

I realized that my right foot was ever so slightly out of position. That was making a big difference. If you feel like your foot is just going to blow off the wall, everything tenses up. I realized I needed to change my foot sequence to get much better friction on the foothold.

When you were successful, did the moves feel easy?

I felt so solid. It was such a cool experience. I was just locked in on all the holds. But, no: it was still really hard!

And the conditions were just magic. It was the one moment over the last ten days when it was actually cloudy and cold enough to climb during daylight. It all lined up to create this one moment in which my skin was good enough, and the conditions were perfect.

When Tommy completed the 20th pitch, I'm sure you must've been feeling mixed emotions: happiness for your partner but also a sense of being so far behind. What was that like?

The way I would describe my mind-set for the past week has been one of pure resolve. I've been just very resolved that I was going to do pitch 15. I haven't let anything else come in. Not even very much happiness.

Of course I was stoked to watch Tommy pull onto Wino Tower [the ledge at the top of pitch 20], but I was kind of preoccupied with my own resolve of what I still had to do.

And I'm still there, to be honest. I have the same attitude about the next three pitches as I did about pitch 15. As far as I'm concerned, they're just as hard. I'm trying not to let any other thoughts creep in. It's dangerous to let your mind go anywhere other than where you are right now.

Did you ever doubt you'd be able to do pitch 15?

Sure. But those moments were fleeting. They were combined with feelings of frustration. I'd pull back to the ledge, having split my finger yet again, and then realize I have to take another two rest days. You're thinking about the timing, the weather, whether or not you're going to have another chance to do it.

But then, you know, 30 minutes goes by and you're back to that state of resolve.

Is it hard to be cramped up on a portaledge for so many hours each day, and then have to step out and perform your best?

It is. But it's also a new normal. You have to go from zero to climbing as hard as you can, really quickly, because your window of opportunity is so small, with the conditions and the light. The terrain doesn't allow much opportunity to warm up in a traditional sense. And neither does the schedule. You just have to pull on and go for it.

What's your morning routine?

If it's sunny, like it is now, we clip our sleeping bags to the outside of the portaledge to stay cool, which I just did. Now we're making coffee and breakfast sandwiches.

What's for breakfast?

Whole-wheat bagel with cream cheese, cucumber, red bell pepper, and salami.

In what ways has Tommy been a teacher to you?

Two ways: attitude and technique. Tommy's optimism is, in a lot of ways, why this route is coming together. It would be really easy to write off the Dawn Wall as impossible.

In terms of climbing technique, I'm learning a new language on this granite. And literally only a couple of months ago, right before we started this push, did that language really start to become fluent.

The climbing has a certain pace to it. It has a tempo. It's about how you step on the footholds. It's so particular.

How important is the climbing partnership in general to achieving hard goals?

I seriously doubt if this project could be completed alone. It's such a huge undertaking. And it's so easy to get crushed under that weight. But when you have a partner, it changes everything.

Tommy and I have very different attitudes and personalities. But I think they balance each other out really well. We each have our strengths and weaknesses as climbers. Over time I think we've found our roles.

At the beginning I was way more likely to defer to whatever Tommy thought. Over time it's become a much more balanced partnership.

You can't be on top of your game all the time. So when I'm down or he's down, we can lean on each other. That part is huge.

Have you taken a moment of pause to appreciate what you're doing? Or are you just so focused on the climbing?

There's a lot of downtime up here. Your mind can wander. It can be as simple as looking out toward El Cap Meadow and realize that you've been living up here for 16 days. I wonder, what am I doing? I can see people down in the meadow, shivering and cheering us on. What is up with that? It makes me wonder about this project and why it is striking a chord with so many people.

Why do you think that is?

Climbing has a lot of themes that are applicable to people, no matter who you are. And a lot of those themes are being recognized in the media: adventure, dedication, vision, belief. That's what this project has required.

And it's not as though these themes don't exist elsewhere in climbing. It's just that we happen to be in a place that everybody knows, on a cliff that's very public and very tall.

What's next?

Today is a rest day. Tomorrow I will try pitches 18 through 20. And I'm not going to lie—I'm nervous about that. I haven't done these pitches yet. But I've practiced some of the moves. I think that if I'm patient and relaxed and I take my time, I have a shot at putting it all together.

Andrew Bisharat is a climber and a writer for National Geographic's adventure blog. Follow him on Twitter.