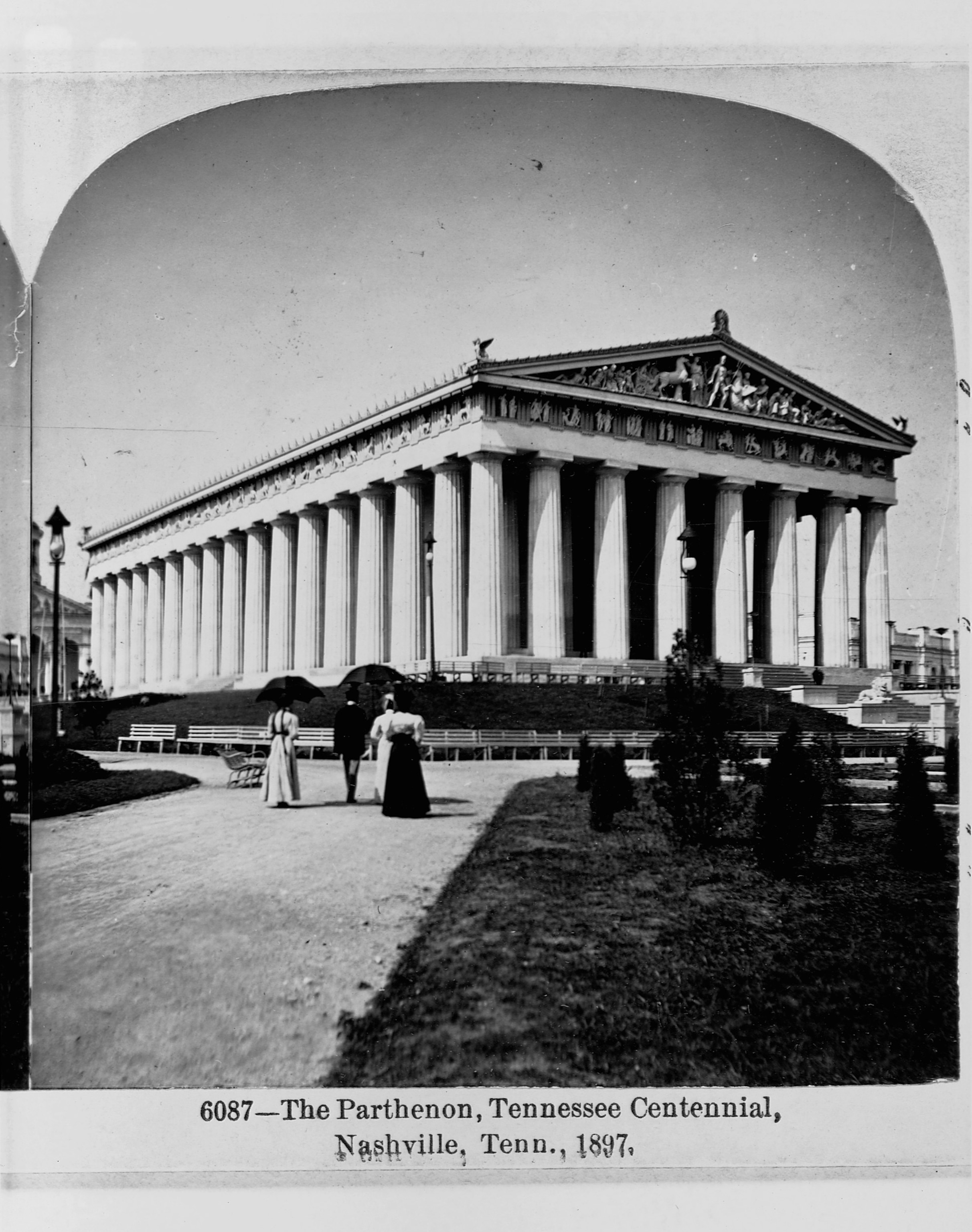

Across a murky pond, under scattered sunlight, stood The Parthenon—at least Nashville’s version of it. I’d driven five hours to the city from my home in Atlanta, looking for a change of scenery after months of pandemic quarantine, only to stumble across the replica of the famous temple in Athens. But what was it doing here? Who’d built it, and why?

The building’s history is more than an homage to a distant wonder. Constructed for the 1897 World’s Fair, it represents Tennessee’s pride and ambition. What’s missing from the grand architecture is an acknowledgment that although the massive exposition was meant to showcase the state’s best and brightest—including the progress made by “the new Negro”—it was a segregated affair.

Today, at Nashville’s site and others like it, this complex racial history is forgotten or erased. But as the coronavirus pandemic drives people to seek safe outdoor recreation—and as a national reckoning on race sparks debates about how to memorialize history—there’s never been a better time to re-explore these World’s Fair sites.

Tennessee’s Centennial Exposition

The history of Centennial Park is laid out on a faded historical marker I almost missed while walking around the area, dodging stray branches and fallen leaves from weeping willows.

In 1897, Nashville hosted the Tennessee Centennial Exposition (aka the World’s Fair), a bustling, multi-month event during which visitors could learn about commerce, transportation, fine arts, and agriculture, among other subjects. From May 1 to October 31, close to 2 million people attended the exposition, which also included amusement rides and shows.

It wasn’t by happenstance that the city’s grand exhibition took the form of the Parthenon: 19th-century Nashville had dubbed itself “the Athens of the South” to position itself as an arts leader and place of innovation. When the fairgrounds opened in what is now Centennial Park, there were buildings spread out as far as the eye could see—more than 300 exhibitions from 85 cities, spanning from the massive Commerce building to the Education and Hygiene building, which offered information about the emerging technology of x-rays. For a fee of 50 cents for adults and 25 cents for children (equivalent to about $15 and $7.50, respectively, in today’s dollars), fairgoers could wander through the marvels of the modern age.

Despite its standard ticket fee, access to the World Fair wasn’t equitable: the exhibitions were segregated. Black attendees were relegated to a single space within the entire exposition, the Negro Building.

“[The Negro Building] was big and was deemed beautiful by all its visitors,” said Wesley Paine, who has served as director of The Parthenon since 1979. She described a building as being in the Spanish revival style, which contrasted with many other buildings’ “vaguely Greco-Roman” design.

Who owns America’s history? The answer will define what replaces fallen monuments.

Across the country, Black community leaders—most notably W. E. B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington—had debated whether or not to take part in the segregated World’s Fair. DuBois and Washington were on opposing sides of the debate, Paine said; despite disagreement, the event’s talks and exhibitions proceeded.

Washington himself appeared at the fair as a special guest on behalf of Tuskegee University, highlighting the important role of what we now recognize as historically Black colleges. Fisk University contributed an exhibit on African Americans and higher education. Professor W. H. Council, the formerly enslaved leader of a technical college that became Alabama A&M University, was another featured speaker.

Despite the forethought required for these massive, months-long exhibitions, world’s fairs were usually temporary in nature—swooping into a city or town for months at a time before disappearing without a trace when the buildings were torn down afterward. Nashville’s Parthenon is the only tangible marker remaining.

Atlanta’s Cotton States and International Exposition

As it turned out, Nashville isn’t the only Southern city with an overlooked history of Black participation in international exhibitions. When I returned home to Atlanta, I went looking for similar stories.

It wasn’t long before I found one at Piedmont Park, near the heart of the city, where the Cotton States and International Exposition took place in 1895. Today, the only remnants of the event are a worn pair of granite steps by a lonely marker. But the exposition was groundbreaking in its day for its inclusion of a Negro Building, without which it wouldn’t have been able to secure vital federal funding.

What role do tourists play in the future of Confederate monuments?

Michael Rose, executive vice president of collections and exhibitions at the Atlanta History Center, explained that world fairs were designed to send a clear message.

“These were huge business and commercial fairs [meant] to show and prove, to the world and the nation […] that Atlanta and the region immediately surrounding it had recovered from the devastation of the Civil War,” he said.

It was a message Atlanta was determined to send: the 1895 exhibition was the third of its kind, coming after two others in 1881 and 1887. Like Nashville’s Centennial Exposition, the Cotton States and International Exposition lasted four months; it ultimately drew in more than 800,000 people.

The Negro Building was situated on the outliers of the exposition, located at what is now the Jackson Street entrance of Piedmont Park. The building was not only a gathering space for Black entrepreneurs, philanthropists, and leaders, but also a space for students from more than two dozen Black colleges and universities to exhibit their artwork.

“There were so many implications about the exposition related to Atlanta’s position in the South—the whole idea of the new South that had been promoted by Henry Grady and what that meant in race relations,” Rose said. “This exposition set up Atlanta as the capital of the new South.”

It was during this exposition that Washington gave his historic “Atlanta Compromise” speech, which advocated an accommodationist philosophy of race relations. Washington’s argument—that the South’s Black citizens should agree to social segregation in exchange for access to economic opportunity—was applauded by many, though DuBois and other Black thinkers feared it would condemn them to indefinite exclusion.

Learn about the fight to save America’s historic Black cemeteries.

I’m from Atlanta, and at first I knew next to nothing about the Black history of the World Fairs that took place in my own backyard. Why? Maybe it’s because little or nothing remains of the buildings that were torn down when the exhibitions closed, and it’s more difficult to remember a place’s history when that place has disappeared.

As national attention focuses on how history is represented in public spaces, massive efforts are underway to recover and share the stories of Black Americans—from the Mellon Foundation’s $250 million investment in more inclusive monuments to a project by the Library of Congress and the National Archives that has transcribed more than 100,000 Reconstruction-era documents.

But at the World’s Fair parks in Nashville and Atlanta, there’s a long way to go. Neither park has active programming to educate visitors about the full history of how those sites were created. Until there’s as much support behind local education efforts as national ones, it’s up to tourists to question what might be missing in the public places they visit.

“We walk the streets, walk the parks, and go about our daily lives truly unaware of the history of where we are,” Rose said. “There’s history everywhere.”