Route 66: Willy, Woody, Mickey & Brad

I’m not sure what’s in the water in Oklahoma, but it sure makes you sing.

And dance, and act, and swing a bat. It makes you witty and dashing and beloved by all—and it makes you famous.

A few minutes after crossing into “Native America” on Route 66, I veered into the small town of Commerce, Oklahoma—hometown of Mickey Mantle, baseball star and New York Yankee superhero.

“Geez, that’s nifty,” I thought, as I motored gently through town cruising up and down the wide streets, not by choice, but by blunder. I quickly noticed that the Sooner State loves its one-way streets, which is how I kept soaring up one side of Commerce without ever getting to soar back down the other.

At some point in my careless laps around town I found 319 S. Quincy Street, the humble home of the “The Commerce Comet”. Then I wandered over to Commerce High School, where kids were running plays on Mickey Mantle field, all of them dreaming of future stardom, perhaps.

Mickey Mantle’s own career followed Route 66 eastbound, playing for the high school here in Oklahoma before moving on to the minor leagues, first in Baxter Springs, Kansas (The Whiz Kids!) and then in Joplin, Missouri (The Miners). Eventually, the kid from Commerce went all the way back to New York and became the greatest switch hitter in the history of American baseball.

Commerce today reminded me of the town I grew up in—it’s the kind of two-story town that most of us grew up in with a half-asleep Main Street where you could play baseball and never get hit by a car.

Right where Route 66 hangs left there’s an old Marathon gas station, built way back in 1927. Whether it was out of filial duty or personal nostalgia (my dad spent most of his career at Marathon) I pulled into get gas. Alas, there was no gas for sale—only Route 66 cookies and soft-serve ice cream. Not enough folks stop in Commerce long enough for the station to need to serve any gas.

Thus Oklahoma continued, one curious town after the next, separated by miles of brown empty earth. Then suddenly there were cattle—big black cattle that dozed and grazed in slow motion. I had reached that hazy border where America stops growing grain and starts growing meat.

Next came Miami, which has nothing in common with the Latin capital in Florida but derives from the American Indian tribe that was relocated to this “Indian Territory” long ago. In Oklahoma, they say Ma-yamuh, which, if said without the local twang, almost sounds Hebrew. Flush up against Route 66, the mighty Miami Coleman Theatre resembles a strange Moroccan castle plunked right down in the middle of a cow town. I felt compelled to stop and have a look, but just in case I hadn’t, there were plenty of signs about town to make me feel guilty about skipping past such an extraordinary and historic property as this.

Though all of America fancied their brightly-lit Broadway dreams, most of America first performed on stages like the Coleman, whose (functioning) Mighty Wurlitzer organ is the last of its kind. Even better, the Coleman still does vaudeville, as if our stayed as innocent as 1929, before all the Wall Street crashes and World Wars that sent millions moving up and down Route 66. Visitors today can still tour the amazing theater, elaborate in its mahogany interiors—when I inhaled that smell of old wood, I imagined this was the kind of place that J.D. Salinger’s parents used to perform with their traveling act; the kind of place where some deadbeat magician pulled rabbits from hats before he turned into the Great and Powerful Oz.

Perhaps America’s greatest vaudeville performer of all, Will Rogers is another one of Oklahoma’s sons who is so famous, he has his own statues (indoor and out.) When I arrived at the Will Rogers Memorial and Museum in Claremore, the white-haired man behind the desk did not charge me any entry fee because they were closing in thirty minutes.

“The last half hour is free,” said the greeter, who may have been as old as Will Rogers (if Will Rogers had lived until now). Walking around the huge hall, I realized that honestly, I knew very little about Will Rogers other than the fact that my grandfather hero-worshipped him, and quoted him all the time.

“Be thankful we’re not getting all the government we’re paying for!” is a timeless one, and as I stood below the great Greek god of a statue of Will Rogers, I scrolled through his quotes on my phone, chuckling aloud in the silent marble hall.

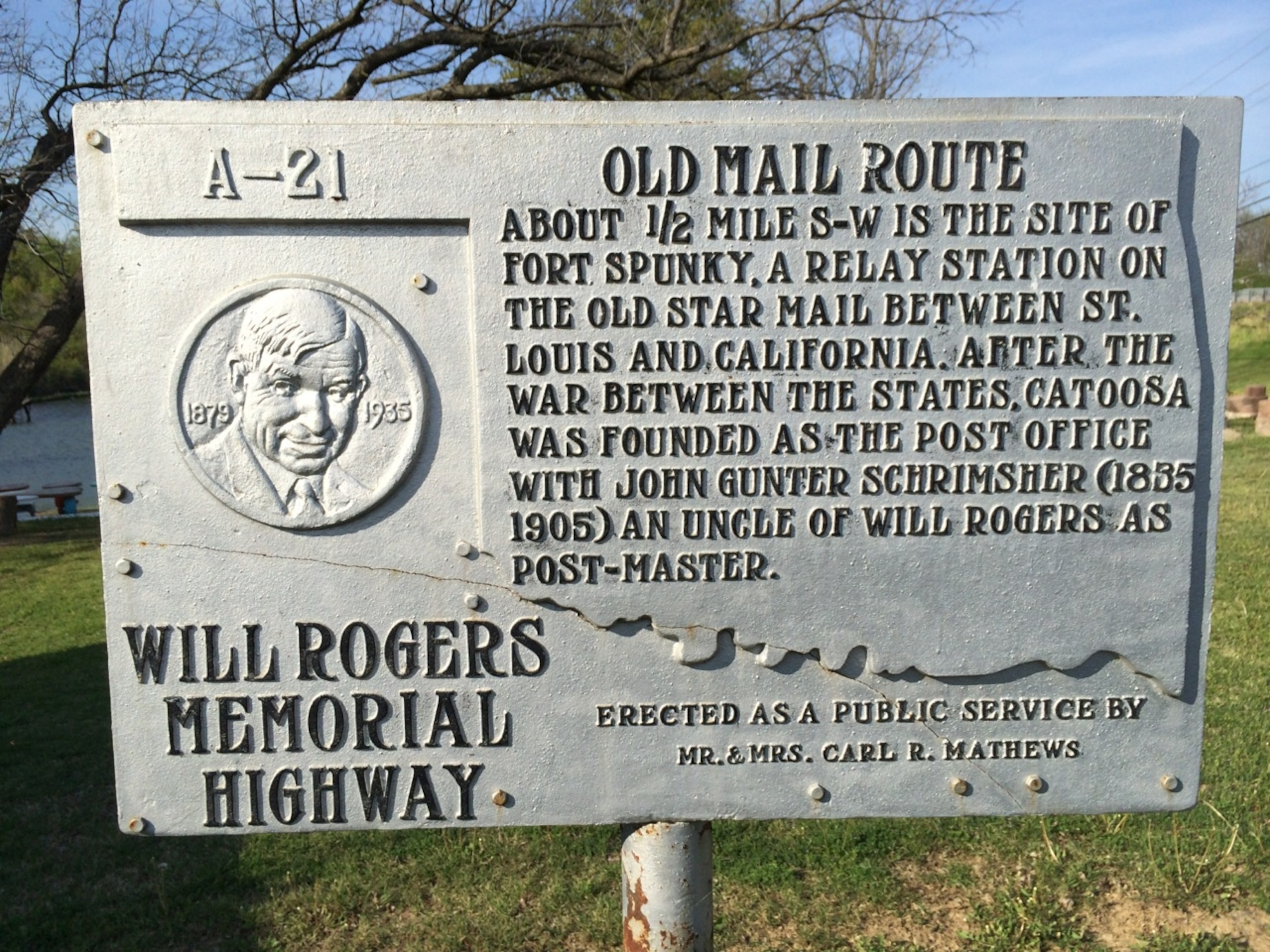

Though he’s remembered for his words and fame, Will Rogers was also a great traveler who explored the far-flung places of the globe long before leisure travel was an option for average Americans. Back then, in Oklahoma, most folks traveled reluctantly, and only after they had lost their land and money during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression. It is fitting then that this road, Route 66, is officially known as the Will Rogers Highway.

It was Will Rogers that said, “When the Okies left Oklahoma and moved to California, they raised the average intelligence level in both states.” His jokes about the Dust Bowl may have been the only good thing about that period of Oklahoma’s history when drought and high winds blew away topsoil and spread bankruptcy like a scourge on the land. It was a tough time in the state, and Will Rogers never forgot his roots. He was a principal advocate for the downtrodden and depressed, the farming poor and the migrant worker, not unlike that other great son of Oklahoma, Woody Guthrie.

The Woody Guthrie Center only opened last year, occupying a sunny corner in the up-and-coming Brady Arts District of Tulsa. Though it’s one of the most contemporary and experiential museums I’ve ever been to, I found myself moving quickly through the interactive displays but getting stuck staring through the glass case at one of Woody’s guitars. It felt like I was staring at the gold sarcophagus from King Tut’s tomb.

The guitar was beat-up and scratched, but in my mind, it shone like a jewel. America’s real treasure is our freedom of speech, and no other music says that better than the poems of Woody Guthrie. The man wrote thousands of songs—all poignant or political or empathetic. Woody understood people—he himself himself was one of the “Okies” he described in song, one of the disenfranchised who left the Dust Bowl days for a better life out west.

Out of all of Oklahoma’s heroes, I think I know Woody the best, if only because every American child learns, “This Land Is Your Land” in their elementary school music class. It’s also the song most foreigners know about America (some claim it’s the unofficial anthem of the United States.)

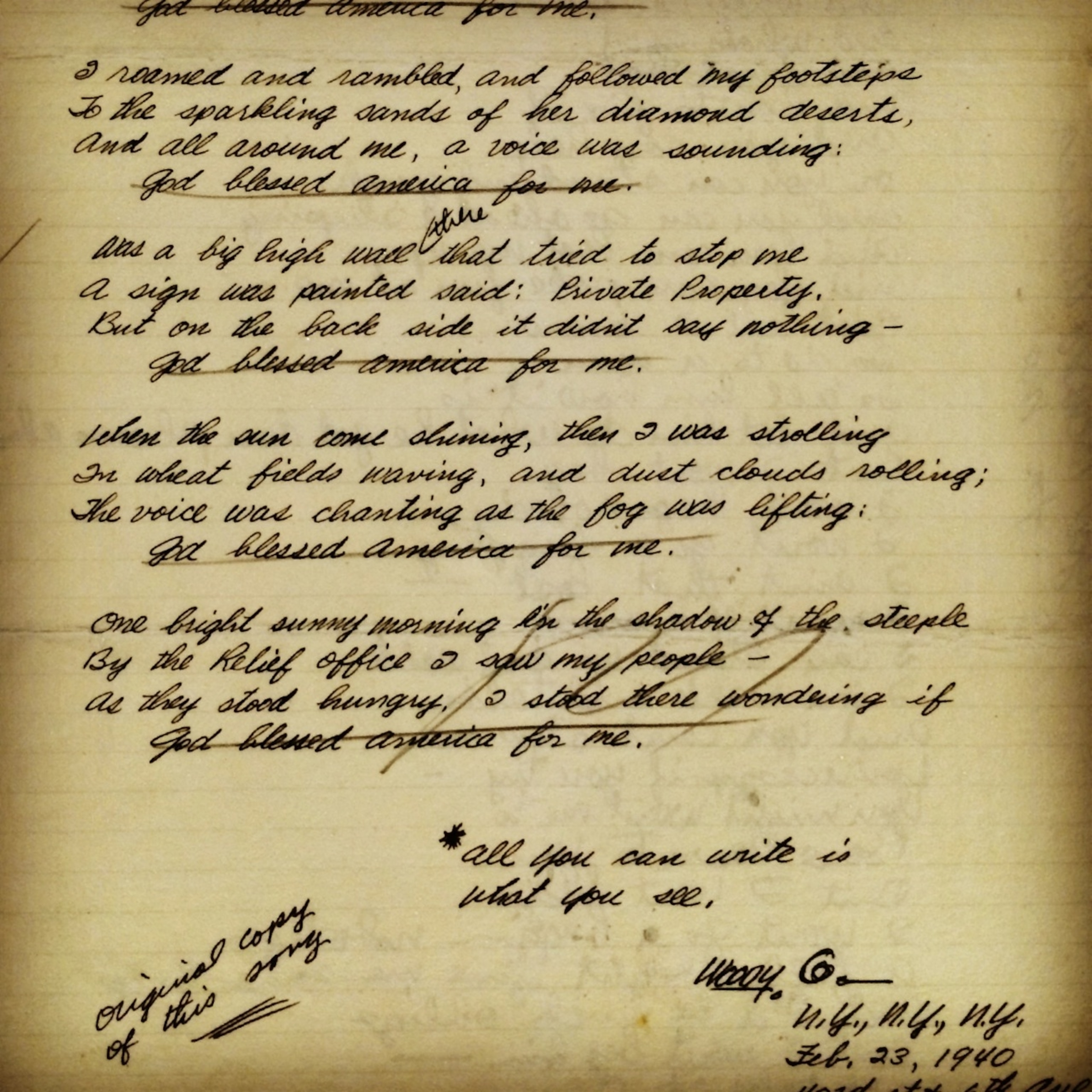

Inside Tulsa’s Woody Guthrie Center, just blocks off Route 66, visitors can peer down at the original manuscript of “This Land is Your Land” written with Woody’s perfunctory penmanship. Foreseeing future nonsense about authenticity, Woody wrote, “Original copy of this song” on the bottom of the page, right after a big inky asterisk, he wrote, “All you can write is what you see.”

All you can write is what you see, and what I’ve seen on Route 66 through Oklahoma is the in-between bits of America where great people are born and raised. I’ve seen the true history of America, which is one of overcoming hardship, cracking jokes in times of adversity, and putting our most political thoughts into song.

I left Tulsa with a set of original Woody Guthrie recordings, and as I continued my path down Route 66, I sang along to Woody’s nasal melodies, feeling strong and funny and wistful, depending on the song.

Of all the tunes I heard, my favorite is Woody’s lullaby to the migrant worker, where he gently sings, “Go to Sleep You Weary Hobo.”

Dulcet and tempoed, Woody’s song spilled up through lost decades and out the side speakers of my rented Chevy. Yes, at times, the road makes me weary too, and though I usually don’t sleep in boxcars, I am, by any dictionary’s definition, a hobo.

I listened to “Hobo’s Lullaby” on repeat all the way to Oklahoma City, which is, coincidentally, the birthplace of another Oklahoman, William Bradley Pitt. Also coincidentally, Brad Pitt’s first breakout role (in Thelma & Louise) took place in Oklahoma, according to the screenplay, on a “fictional road between Arkansas and the Grand Canyon.” That non-fictional road is Route 66, which is the same road that Brad Pitt traveled when his family moved back east to Springfield, Missouri.

In my humblest hobo’s opinion, Brad Pitt doesn’t hold a candle to Mickey Mantle or Will Rogers—and especially Woody Guthrie—but all four men hail from Oklahoma and all four men grew up on a two-hundred mile stretch of Route 66. There are many others, too, I’m sure, like Garth Brooks, whose hometown of Yukon lies due west of Oklahoma City.

There’s just something about Oklahoma. America’s famous people may live in Malibu or Manhattan, but Oklahoma is where they come from; this is where the show begins—on high school baseball fields and vaudeville stages, in farmer’s barns and juke joints and cowboy bars. Oklahoma is one of the sparks that lights America’s fire—no wonder it’s on Route 66.