Human Ingenuity Can Fix Past Mistakes and Shape the Future

Our mistakes are legion, but our talent is immeasurable, says award-winning author Diane Ackerman.

In her new book, The Human Age, Diane Ackerman, best-selling author of The Zookeeper's Wife and A Natural History of the Senses, takes us on a journey into the Anthropocene: the era in which humans have both mastered and degraded the natural world. Ranging across the globe, she shows how our unique talent for self-awareness and our technological prowess can help us overcome today's global challenges.

Speaking a few days before what may be the largest ever climate change demonstration, in New York, she talked about the Frozen Ark, where the DNA of vanishing species is being collected, introduced us to an orangutan with an iPad and a group of Alaskan Inuits threatened by rising sea levels, and expressed her optimism about the future.

You call our era the Anthropocene age. Can you explain?

Human beings have been on the planet for about 200,000 years, but if you think about it, most of the wonders we identify with contemporary life came about in the past 200 years. And in the past 20 years, they've been advancing at a mind-boggling pace.

We've now changed the course of rivers, we've changed the outline of continents, we've created giant megacities, and we've even played golf on the moon. We've so dominated our landscape that the coalition of scientists believes we have to change the name of the era in which we're living.

We're in the Holocene, a geologic era like the Jurassic for the dinosaurs. But [scientists would] like to change it to something that conveys more of our imprint on the planet, the Anthropocene, which translates as the human age. And I think it's a very good idea.

At the beginning of the book, we meet Budi, a young orangutan who lives in the Toronto Zoo and is involved in a program called Apps for Apes. Can you tell us a little bit about this program?

Orangutans are terribly endangered. Their rain forests are being leveled, and palm plantations are being planted. Orangutan Outreach has a program called Apps for Apes. They provide iPads for these wonderful, smart apes to play with and enrich their minds.

I was at a zoo and watched Budi use Skype on it. Maybe it's the first step before the interspecies Internet, which the singer Peter Gabriel talks about. It's a remarkable program. Another thing it will perhaps do is make zoo visitors look and say, "That could be my son over there." And maybe that will make people identify more closely with these animals.

Budi's keeper observes that humans may not be as smart as we think, because we're so easily addicted to screens, while Budi is not. Is technology making us dumber?

It's hard to say how technology is affecting us. But it definitely is. All of our experiences wire and rewire the brain. And using screens and visiting nature virtually is like that.

One theory now is that kids who are in wealthier countries and have a lot of screens available to them are getting more near-sighted. They're not spending as much time outside and allowing their eyes to travel to something close, then something far, to develop their eyesight. Our thumbs are also getting bigger from texting so much. So we're definitely changing ourselves.

One of the factoids that jumped out at me is that one in every 200 males is related to Genghis Khan. My wife is always saying I'm a Neanderthal. So she's got it wrong?

[Laughs] Well, you could be part Neanderthal also. A lot of us are Neanderthal. But in the case of Genghis Khan, he swept across Asia and into Russia and, of course, left a trail of offspring. They reproduced, and their offspring reproduced, and so on.

This is going on all over the world all the time, and throughout the animal kingdom. Genocide, unfortunately, is not new. It's very old in human terms. But it's also something that happens among other animals. A male lion will come in, kill another male lion and take over the pride and kill the offspring, so that only his genes will survive.

But though that's a natural thing for nature to be doing, we're a different kind of creature. We don't always play by nature's rules. And when we recognize what is happening, we're able to change our behavior.

This is not a depressing book—in fact, it's largely positive and heartening—but you do face squarely the issue of global climate change. Tell us about the Yup'ik.

The Yup'ik Eskimos are going to be our very first climate refugees. They're being swept away by the seas that keep encroaching into Alaska. Soon they're going to have to move to higher ground.

And this is happening all over the planet in lots of low-lying island nations where people are applying for status as climate refugees. We don't really have that status, though. You can be a refugee for political reasons, but climate? We haven't really kept up with that. However, we're going to see more of it.

And part of our task, as we deal with climate change, is to help the most vulnerable among us adapt while we're trying at the same time to bridle the changes that are taking place.

You elaborate on a number of amazing new technological developments and scientific discoveries that are helping us to cope with change. One of my favorites is how the South Koreans have created wind tunnels in their subway system that heat office buildings aboveground.

We don't have to have renewable energy in the old-fashioned way. In some parts of the world people are collecting wind from passing subway trains. In other places they're collecting heat from human commuters at train stations. Each person gives off a hundred watts, and that can be gathered and pumped underground, where it heats water. Then that water is used to help heat apartments. The wind tunnel idea creates electricity to feed back to a central grid.

We're starting to do that in the U.S.—but not enough. We really need to focus more on as many renewables as we possibly can at the same time that we are imposing a tax on carbon and insisting that the power plants reduce their emissions. Forty percent of our greenhouse gas emissions come from the power plants. By working to get those reduced, we will be doing a great deal.

I also hope people will reject the whole idea of the XL Pipeline carrying tar sands oil from Canada. Saying No to that would also go a long way to reducing emissions.

Do you think that Americans, with their deep distrust of government, are ready for these changes that may raise energy costs and put people out of work?

It might put some people out of work at coal-fired power stations. However, renewable energy has become affordable much faster than anyone ever thought it was going to be. Solar is vying with fossil fuels now, and that industry is burgeoning. There are more jobs needed there.

I'm a kid of the '60s, so I remember living through a lot of moral collisions of this sort. There was integration, women's rights, the Vietnam War, gay rights. What we discovered is that the younger generation really can make themselves heard and bring about legislative changes. And I think America is ready for that.

One of the paradoxes you explore is that Homo sapiens is both destroying and attempting to save the planet. Which side of our nature will win?

I'm an optimist, so I predict that the good side will win. We're doing things like trying to create new species at the same time that we're causing some species to go extinct. The one thing that is our greatest achievement-bigger than any of our scientific discoveries-is our self-awareness, our ability to stand and look at ourselves and see what we're doing and decide if this is who and what we want to be. What kind of species do we want to be? What kind of planet do we want?

And we're now in a position to make those kinds of decisions for the first time in the history of this planet. We're not helpless. We're not powerless. We're not doomed. We can still slow down climate change and have a big say in designing the kind of planet we want, and also need to survive.

Your research took you all over the world. Were there any eureka moments?

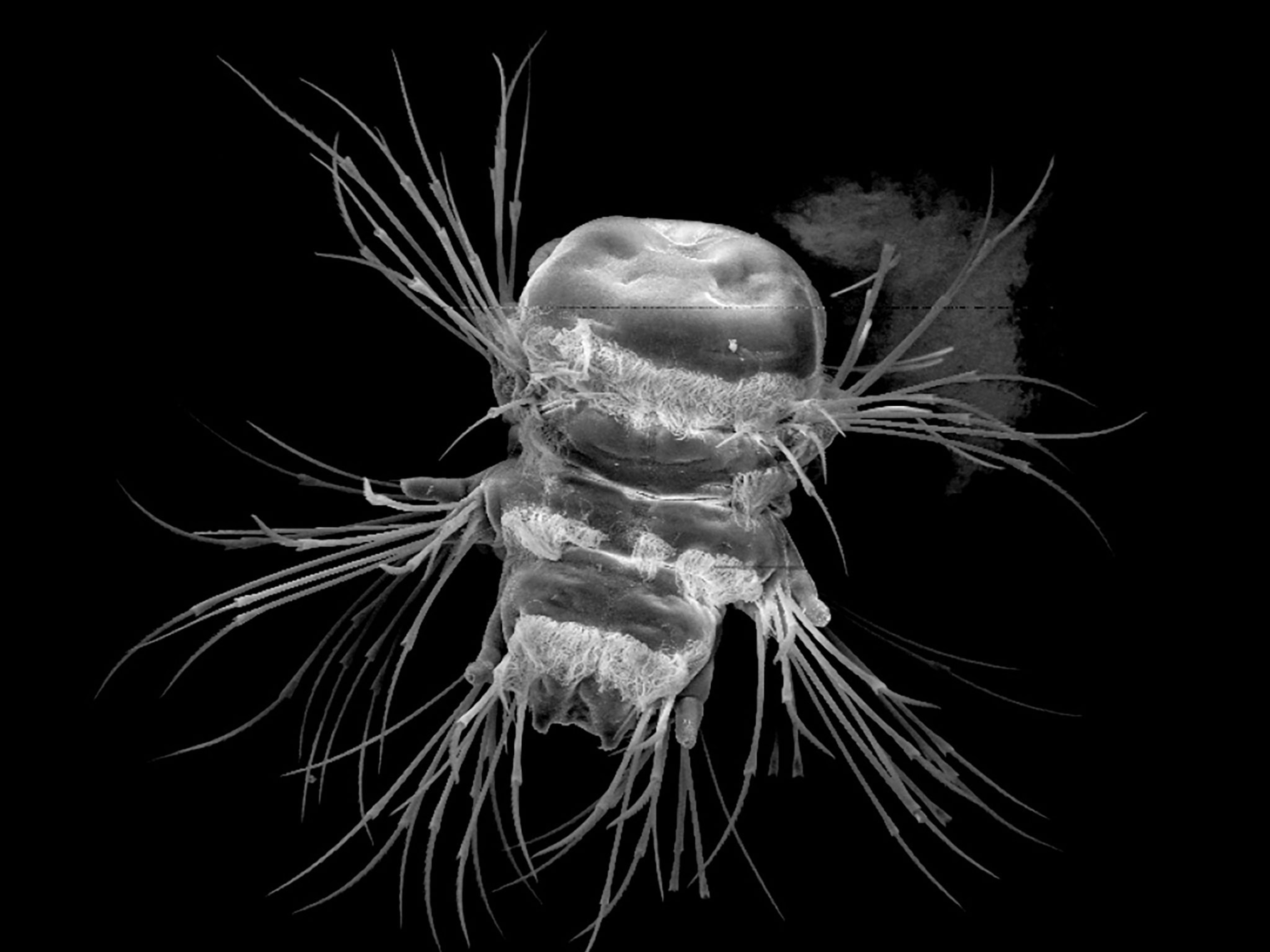

Oh, I loved visiting the Frozen Ark at Nottingham University, in England. They store the DNA of most of the world's animals. They began by storing the DNA of the world's most endangered animals, but then they realized they needed the whole ecosystem. What if the rest of the animals become endangered?

So now they're collecting the DNA of all of them, freezing it against the day when we may need those genes to re-create some of the missing animals, or have sperm that they can then use to impregnate one of the last surviving females. Or to enrich a dwindling gene pool.

When I saw that, I realized that in some cases now extinction is not forever. Of course this opens up all kinds of ethical questions. We could, theoretically, bring back a Neanderthal or a woolly mammoth. But should we? These are ethical questions we have to ask ourselves. And for the first time we're in a position to do that.

What was it like for you to consider your life and your fellow humans as someday being part of the fossil record?

I find it fascinating that there will be a strike in the fossil records from our era that will include things like plastics. When I was growing up in the '50s and '60s, things like frozen food and plastics were just coming in. We take it all for granted now. But it's very, very recent.

And these things are going to linger in the fossil record for a long time. Our descendants are going to be able to see radioisotopes from nuclear waste and all kinds of discarded metals and plastics, or the record of monocultures from factory farms. Where there used to be biodiversity, suddenly there will be pollen from just one kind of plant: miles and miles of nothing but corn and wheat. We're going to see huge changes in our time period.

One of the intriguing examples of human ingenuity you give is in a chapter called "Printing a Rocking Horse on Mars." Will we really be able to do that one day?

I visited a scientist at Cornell who is printing out 3-D ears with [a device that] looks about the size of a toaster oven. It's actually a 3-D printer, whose ink is living cells, and it works just like an ink jet printer. It goes back and forth, but instead of ink it lays down minute layers of living cells till it has built the thing up in three dimensions. So yes, in theory we could print a rocking horse on Mars.

In the case of the ears, these ears are for children who are born with deformities. It's very hard on them as they get ridiculed a lot. So this scientist, who has small kids of his own, decided to work on this project. While I was standing there, he handed me a beautiful little ear!

The 3-D printers can also mix and provide drugs to areas that desperately need them but are very remote. All of these things are right on the edge of coming about. They'll be happening in the next 50 years.

You say at the end of the book, "We are at a great turning point, our own momentous fork in the crossroads, behind us eons of geological history, ahead a mist-laden future." Are you excited about the future?

I'm very excited about the future. I think this is a very exciting time to be alive. We have lots of challenges. But we also have many opportunities to use our intelligence and creativity to find solutions to very complicated but fascinating problems.

I think it's a time of great adventure, and I'm happy to be alive at this time. It's a time of exploration in many, many fields. [Laughs] I just wish I could come back in a hundred years and see what had happened!

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.