These Satellite Views of Ancient Earthworks Are Stirring Debate

Images of mysterious shapes inspire intriguing theories, but solid answers will come from on-the-ground study, archaeologists say.

After watching a television show about ancient pyramids built outside Egypt, Dmitriy Dey wondered if his own Central Asian nation of Kazakhstan might harbor such exotic ruins. A business manager in the northern city of Kostanay, Dey began to study satellite images on Google Earth during his off hours.

He found no pyramids, but he did spot dozens of odd, human-made features scattered across a remote area of the steppe that’s half the size of New Jersey.

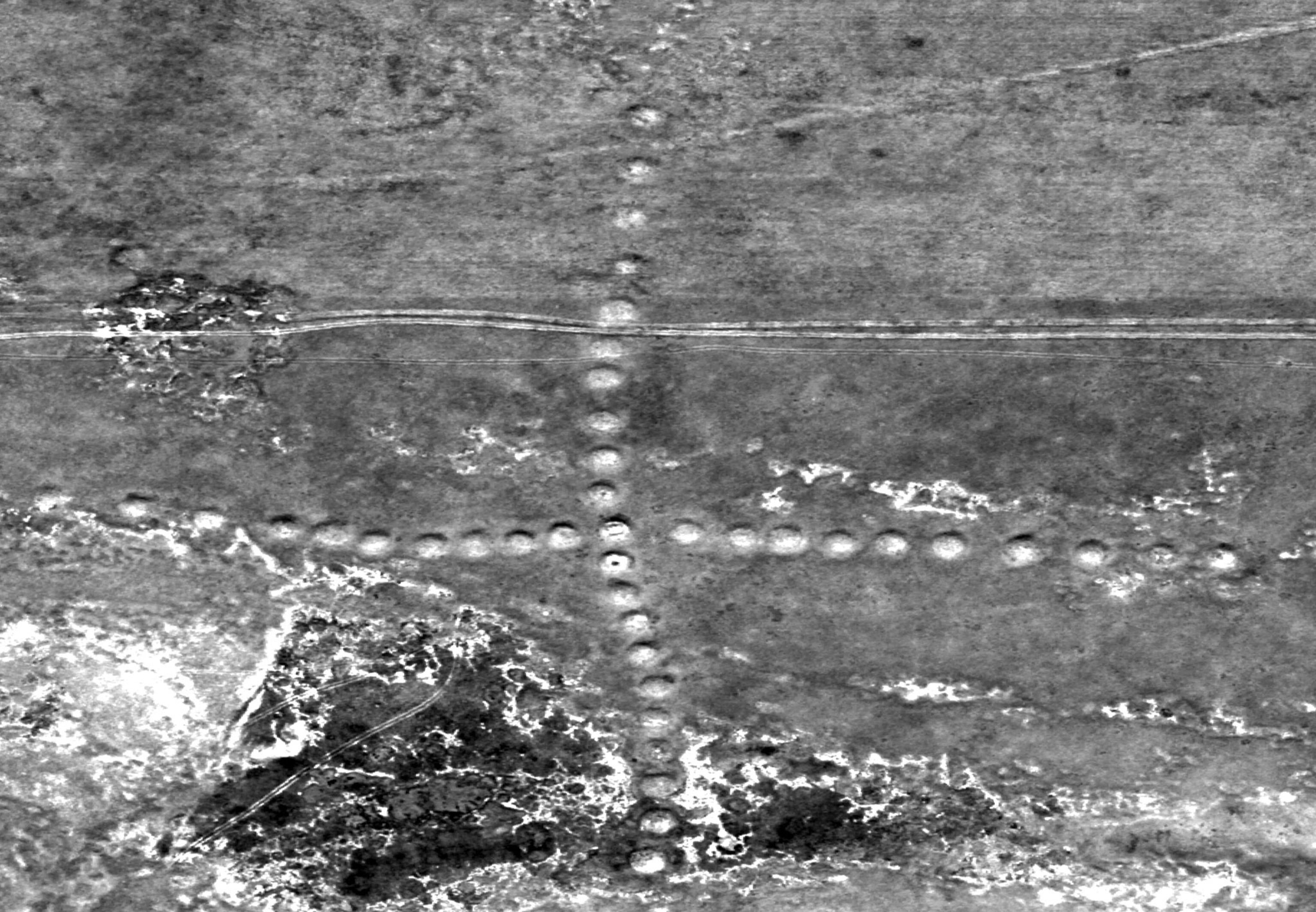

Eight years after he saw the TV show, Dey’s unusual discovery is stoking a public debate about these peculiar mounds and earthworks. Though barely noticeable on the ground, the forms take on a dazzling array of shapes—including huge circles, crosses, squares, and swastikas—when seen from high above.

But archaeologists disagree on the age, purpose, and even the number of the features, which are reaping widespread publicity thanks to dramatic satellite images released recently by NASA.

Dueling Over Dates

“It required immense effort to build these,” says Giedre Motuzaite Matuzeviciute, an archaeologist at the Lithuanian Institute of History in Vilnius. Matuzeviciute is part of an international team, led by Andrey Logvin of Kostanay University, that has studied two of 55 sites identified as human-made features on the Kazakh steppe. “The soil there is very heavy, like clay. And the earthworks are located in the middle of nowhere.”

Located in the Turgai region of central Kazakhstan, in a sparsely populated area, the earthworks include 21 crosses, one square, four rings, and one swastika-like feature. Many cover territory larger than a football field.

Matuzeviciute, who learned about the features four years ago and who credits Dey with their discovery, says that there are two distinct types. The first group is located on high plateaus overlooking river watersheds. The second group, including one swastika-like symbol, is located along rivers and close to burial sites associated with the early centuries A.D. Swastika-like signs are common across ancient Central Asia.

Matuzeviciute’s group used modern dating methods that pinpoint construction of one earthwork to 800 B.C. and another to 750 B.C., a time when the Iron Age was dawning and the first towns and monumental buildings appear in the area. “These dates don’t surprise us,” she adds. “This was a period of transition.”

Since her team could not find organic material that would provide radiocarbon dates, it used another method called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) that measures how long it has been since a sample was exposed to sunlight. The dates are accurate within 20 years.

Dey and his research team claim that the features are as old as 8,000 years, based on the rate of erosion of the mounds, along with finds of Neolithic flints around the sites.

But flints could have become mixed into the earthworks at a much later date, counters Matuzeviciute, while erosion rates are difficult to ascertain. Though no dating or excavation work has been done on this second group, Matuzeviciute suspects they are less than 2,000 years old.

Celestial or Down-to-Earth?

The purpose of these features is even less clear than their age. Dey contends that they are solar observatories that were part of a Neolithic sun cult. “I’ve done the calculations,” he says.

But archaeologists are deeply skeptical of such an interpretation. “These could be a grab bag of anything, from animal corrals to Soviet water works to stone circles,” says Michael Frachetti, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis who excavates in Central Asia but is not involved in the research. Claiming that the features are related to a Neolithic sun cult “is not necessarily wrong,” says Frachetti. “It just doesn’t qualify as science.”

Matuzeviciute acknowledges that much more research must be done to get clear answers, but she says the features don't match the typical shape of corrals, and that they clearly predate Soviet times. She suggests that the plateau earthworks might be related to the migration of the saiga antelope, a nearly extinct mammal that once was a mainstay prey of Kazakh hunters.

“They may have been built as a kind of landmark, something that could be seen from river valleys far away,” she says. “These aren’t like the Nazca lines that you can only see from above.”

The second group of features, meanwhile, could have been a form of tamga, or symbols used by Eurasian tribes as animal brands and territorial markers.

Dey counts 260 features, but Matuzeviciute says that figure includes a host of burial mounds, called kurgans, created in later periods when Turkish tribes lived here, as well as some features that likely are more modern corrals. She estimates that there are about 55 ancient earthworks, only half of which have yet been seen on the ground by researchers.

“You can misinterpret these sites using only satellite images, without visiting each site,” says Matuzeviciute.

In the past, Matuzeviciute and Dey collaborated in their research, but that has changed. “Dey used to provide coordinates of new objects, but he stopped doing that and went his own way,” adds the Lithuanian archaeologist, who studied at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom.

Both teams hope to publish papers in scientific journals in coming months. “These features certainly look human-made,” says Sarah Parcak, an archaeologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who uses remote sensing for much of her research. “But we are waiting to see if peer review gives this the thumbs up.”

Dey, meanwhile, says that he has left his day job to work on the project full time, and is hoping to obtain the resources to continue his research. “We are a young country,” he says, “But this work helps us to see the impressive work of our ancestors.”

Follow Andrew Lawler online at www.andrewlawler.com.