Veteran Explorer of Disappearing Forests Charts New Course

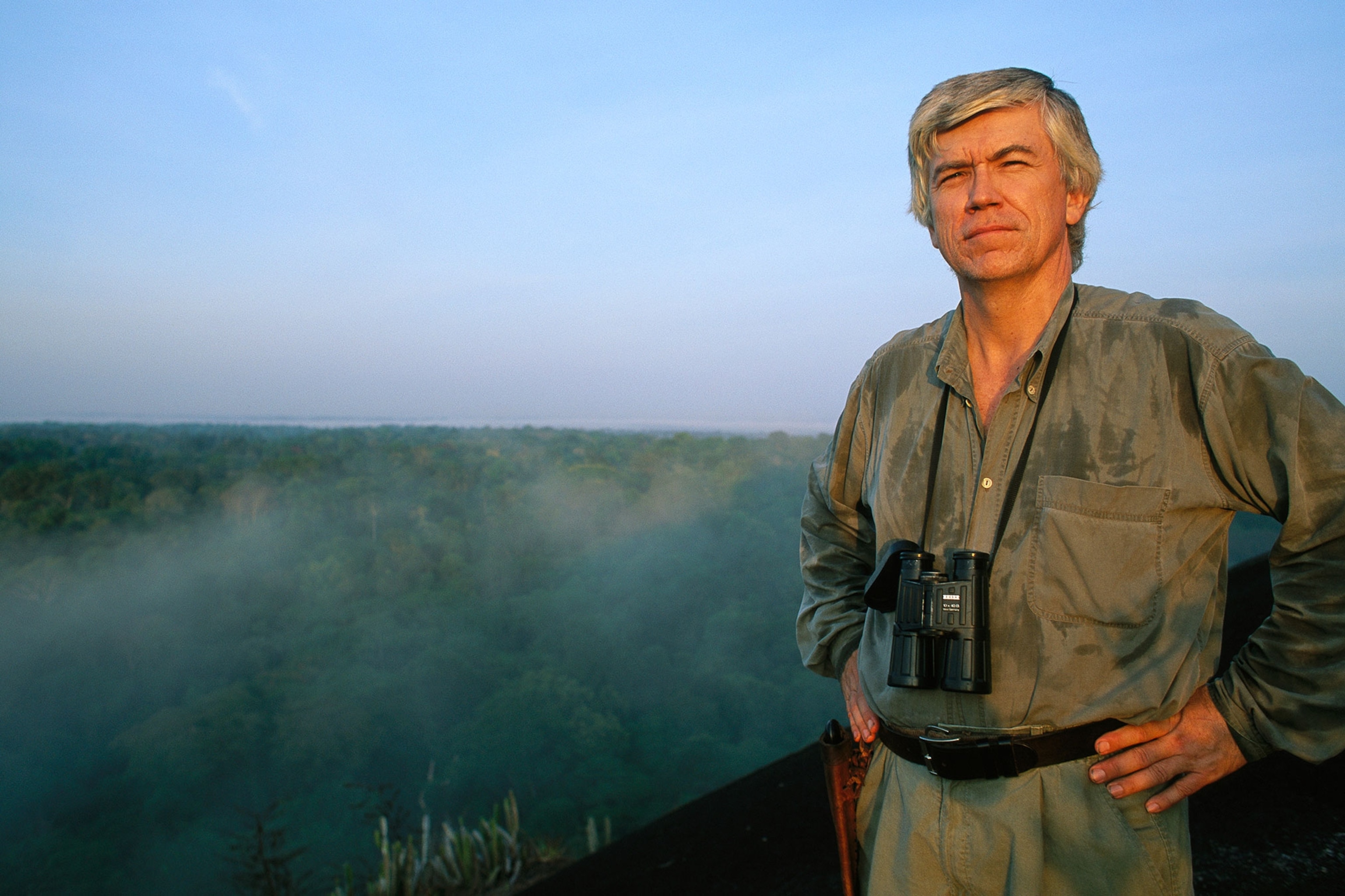

Exclusive: As he joins Global Wildlife Conservation, Russ Mittermeier talks about the future of saving species.

Farming, logging, and even diseases like Ebola join a long list of forces currently erasing forests and animals from the planet. The trends can seem desperately bleak—a recent analysis shows global tree cover loss rose 51 percent last year.

No one knows this story better than Russ Mittermeier, who has been working to stave off biodiversity loss for almost five decades in places such as Madagascar, Brazil, and Indonesia.

Now, after decades of leadership at Conservation International, the eminent conservationist and primatologist is embarking on a new career phase as chief conservation officer at Global Wildlife Conservation, a nonprofit that aims to protect species in part by encouraging collaboration among researchers, industry, and policymakers. (See the group's posts on National Geographic's Voices blog.)

The addition of Mittermeier "exponentially increases our ability to rally other partners, to advance on saving the smallest, rarest and most vulnerable tropical species, and to create long-term positive impact on the biodiversity of our planet," says Brian Sheth, Global Wildlife Conservation co-founder and chair.

Saving tropical forests, and the creatures that live in them, Mittermeier points out, isn't just about preserving the world's natural wonders. Humans need these forests for our own survival, not least because they absorb the greenhouse gases that stoke climate change.

Below, in his own words, Mittermeier describes why he sees plenty of reason for optimism.

A lot has been lost, but there is plenty left to save.

What remains in the [world's biodiversity] hotspots is a little more than two percent of the Earth’s land surface. Yet in that area you have more than 50 percent of all plants and more than 40 percent of all vertebrates—endemic species found nowhere else. Parallel to the hotspots, you have other parts of the world that are also high in biodiversity with very high levels of endemism, but they’re still largely intact—the Amazon, the Congo forests of central Africa, and the island of New Guinea.

I’ve particularly focused on the Guiana Shield region, which is the northeastern corner of the Amazon. This the most intact, most pristine tropical forest region on Earth. I’ve been working there since 1975, particularly in the country of Suriname, which has the highest percent tropical forest cover of any country on Earth—about 94 percent. When I go to Madagascar [with more than 90 percent biodiversity loss] and get a little bit depressed, I have to come back to the Guiana Shield and see that there is still some hope in some parts of the tropical world for conserving large intact ecosystems.

The world is filled with people who are taking action.

What attracted me to Global Wildlife Conservation is that it is a species-focused organization, and given my interest in species conservation it is a perfect fit for me. I’ve been looking for an organization that was focused on species and has the potential to grow at scale, and GWC really is the place right now. I’ve known [GWC CEO] Wes Sechrest for a long time, and I only recently met [GWC co-founder and chair] Brian Sheth a few years ago, but Brian is terrific. He represents a newer generation of philanthropists that is really going to be the wave of the future and has the potential to change the course of conservation history.

A lot of the work [in conservation] is done by the superstar field people who are out there on the front lines. If you can find those people and empower them, that to me is one of the key ingredients of success in this business, and that’s been a very basic philosophy of Global Wildlife Conservation since the outset. Hire those superstars, don’t micromanage them, let them do what they are so good at doing. Very often, they’re living out in the middle of the wilderness for years on end. But without the dedication and the commitment these people have, it’s going to be very difficult for us to succeed in the future.

Another one of my big interests is working with indigenous communities to empower them, because they are the stewards of a very large portion of the world’s remaining intact ecosystems. In Suriname over the past couple of years, we’ve worked with two groups of indigenous people to create a reserve of 7.2 million hectares—that’s about 18 million acres of largely pristine forest.

Saving species can also create economic opportunity.

I have long been promoting the idea of ecotourism, getting people out to visit remote areas and to work with local communities in top priority sites for biodiversity. This is based on a birdwatching model. My oldest son is a world class birder, and I’ve seen how incredibly well connected this birdwatching community is. This is a multibillion dollar industry in the United States alone, and there are about 50 million people that self-identify as birdwatchers.

This is enormously powerful. Why not apply this to other creatures living in tropical forests? The best model you have out there with a track record is mountain gorillas. Mountain gorilla tourism is a major source of foreign exchange for Rwanda and Uganda. They just raised the price for an hour with mountain gorillas in Rwanda to $1,500 for one hour. They’ve still got a long line of people coming to visit.

Over the past couple of decades we’ve been working with local communities to develop guide associations around the highest priority protected areas in Madagascar. You get people with an elementary school education who have trained themselves with a little bit of support from us in biodiversity conservation, and they understand what’s out there as well as any scientist. They become the guardians of the forest. I’ve found ecotourism to be the fastest way to demonstrate quickly that conservation pays.

Researchers are doing more than gathering knowledge.

Long-term research sites in high-priority areas are more effective than any guard force, and they’re better at engaging local communities than just about any other mechanism. For instance, in west Africa, if you have a functioning, long-term research station, you’re going to find animals at reasonably high—and sometimes close to pristine—densities. In surrounding areas, you may find very little, because bushmeat hunting has eliminated virtually any larger animal.

I don’t know how many times I’ve gone to places and said, you guys have this species of primate, or turtle, or whatever it is, that no one else has anywhere in the world. And they look at me and say, “You mean you don’t have these in the U.S.?” They [realize], wow, so these animals here are special.

You can help too, and have fun in the process.

Get out there into nature: Don't just watch television, and don't just read about it. Get out into the woods behind your house or in a park near where you live, but also [consider] getting out and visiting these tropical places as an ecotourist. It's not that expensive, and it's easier than it's ever been. I come from a modest background, and yet I've been to 169 countries.

We all have to become ambassadors for conservation. You see real leadership emerging from this younger generation. They're so much more educated and so much more aware of environmental issues than ever before.

I’m by nature an optimist. You run into obstacles, you have failures all the time, but you roll through them. I wouldn’t be in this business for close to half a century if I didn’t feel that there were possibilities and opportunities for success.

This conversation was edited for length and clarity.