Climbers Crush 'Unbeatable' Speed Record on El Capitan

Meet the climbers who beat Alex Honnold and Hans Florine's record on the Nose by four minutes.

For big-wall climbers, El Capitan in Yosemite National Park is the most famous piece of rock on Earth. On Saturday, Brad Gobright and Jim Reynolds scaled its most iconic route, the Nose, in 2:19:44, breaking the 2012 speed record set by Alex Honnold and Hans Florine by nearly four minutes.

The first speed ascent of the route was set in 1975 by John Long, Jim Bridwell, and Billy Westbay, with a time of 17 hours and 45 minutes. Over the following decades, the record was broken 18 times, often by some of the most respected big-wall specialists of their generations.

Most climbers considered Honnold and Florine’s time unbeatable. Honnold—the first and only climber to free solo El Capitan—holds multiple speed climbing records, and Florine has set the speed record on the Nose eight times. The pair broke the previous record, set in 2010 by Dean Potter and Sean Leary, by almost 13 minutes.

Gobright, a professional climber, and Reynolds, a member of the Yosemite Search and Rescue team, began working the Nose together in spring of 2016.

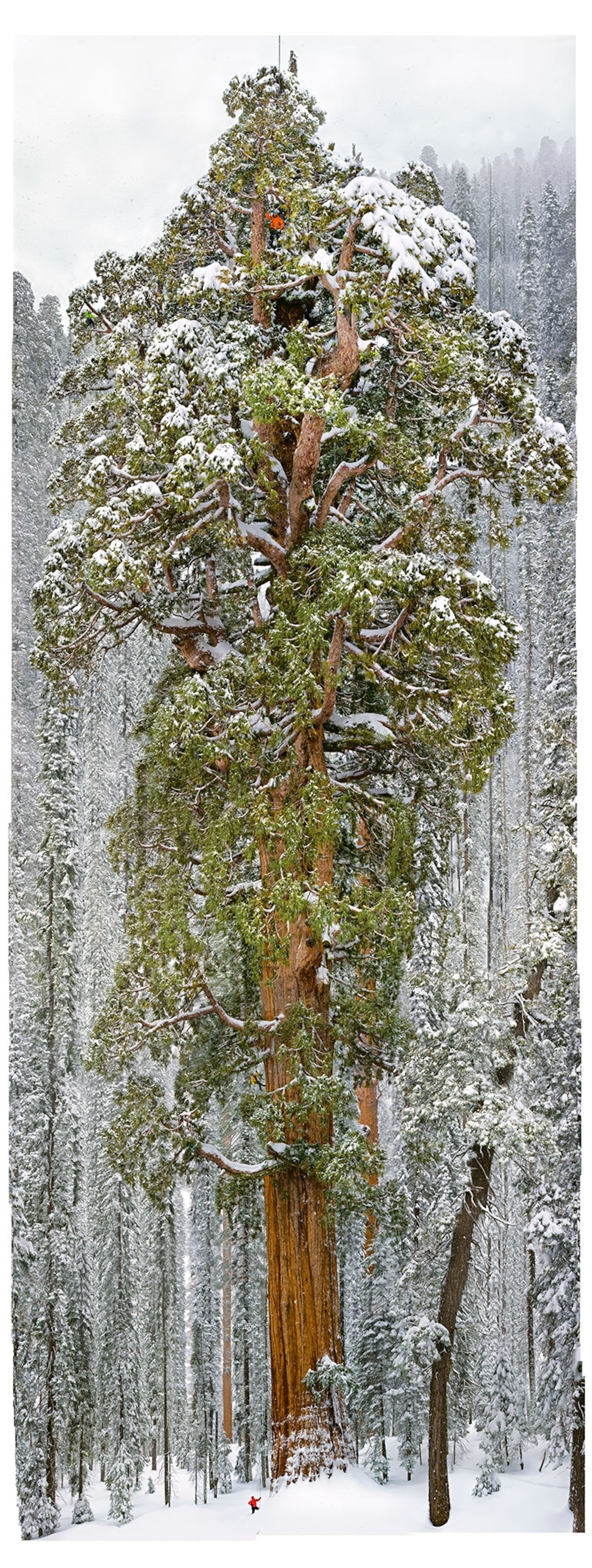

The route begins at the foot of El Capitan and follows the center prow 2,900 vertical feet to the wall’s tip. If the Empire State Building and Chrysler Building were stacked next to it, the Nose would loom above them for another 10 stories. Pairs of experienced climbers are lucky to finish it in four days.

Just before dawn on Saturday, Gobright started up the wall, followed by Reynolds.

“We had discussed bailing that morning,” says Reynolds. “We didn’t know how many more laps we had left in us, and there were a lot of climbing parties on the wall.”

A few minutes after 9:00 a.m. PDT, Gobright pulled himself over the lip of El Capitan and raced to the nearby tree which marks the finish.

“It feels good to be a part of that piece of Yosemite history,” he says. “I don't think the record will last long, but it's nice to get the race started again.”

We spoke with Gobright and Reynolds about their record-breaking ascent.

What inspired you guys to chase the speed record for the Nose?

Brad Gobright: I like setting goals that are way beyond my reach then practicing until they become possible. The Nose was the first route Jim and I ever did together. We made a great team, so we set a huge challenge.

I like setting goals that are way beyond my reach then practicing until they become possible.Brad Gobright

Jim Reynolds: El Capitan has always been so inspiring to me. The first time I came to Yosemite, I wanted to get on it. Every season I’ve been in the [Yosemite] Valley, I’ve sought new adventures. I was lured in by the speed record because it was such a different type of challenge.

When did you start working on this project?

JR: We started trying in the spring of 2016. It seemed so beyond impossible that we’d joke, "if Dean [Potter] can do it, we can do it." By the end of fall 2016, our best time was below three hours—I felt like that was a lifetime accomplishment, but we agreed to try again in 2017.

Then, last February, Brad broke one of his ankles while climbing near Vegas. I returned to Yosemite in April, put in some relaxed laps, and those helped me learn the route’s intricacies. Brad and I started trying again this September once he’d healed.

BG: By the end of last fall, we knew we could possibly get it this season, which added to our stress. Once we broke into the 2:20s, we knew that any small mistake could blow an attempt.

What made you a great team?

BG: We're both pretty bold, but we also know our limits and when to draw the line. I trust Jim—he communicates when he’s concerned. And he doesn’t do anything that could kill us.

JR: Brad is an animal, especially at free-climbing. It’s nice to know he probably won’t fall during a route, whether it’s 5.9 or 5.11+. I’m more of an all-arounder. Aid-climbing is part of my skillset, so I took the lead on those sections.

What was your strategy for shaving down time? Did you tweak it during practice?

BG: It came down to extreme detail on certain moves and gear placements. We marked some holds with chalk, did slower runs to dial in [the most challenging] crux sections, and studied videos of previous ascents. After each attempt, we walked down the back of El Capitan and discussed improvements.

Eventually we settled on doing long runouts, so we practiced the dangerous sections until we could do them safely. I led the first half of the climb and Jim led the second half.

Had you talked strategy with Alex Honnold and Hans Florine?

BG: They both gave us great advice. Honnold and I discussed how to do gear exchanges quickly, and Hans explained some strategies for the pendulum bit [the “King Swing”].

Any nerves as you approached the base of the Nose?

BG: We were nervous because a week earlier, our friend Quinn took a big fall on the route and got very injured.

JR: Usually my “early morning dread” fades by the time I get to the base of the Nose, but since Quinn's accident, I haven’t been able to shake my fear until I start climbing. It made me question what we were doing.

What was the last thing you did on the ground before starting your climb?

BG: Same as always: we asked some Europeans if we could go first. Usually, 80 percent of the climbers on the Nose are Europeans. No Joke.

Ok, so what happened that day on the wall? How’d you tackle the climb?

JR: We mainly simul-climbed. Unless we were on a difficult section, we kept a ton of slack in the rope. Brad short-fixed me on the first four pitches, and I fixed him on a lot of the higher ones. We really relied on free-climbing and avoided questionable gear. We also avoided using cams and nuts [protective gear], and only added one sling.

For about 85 percent of it, if one of us fell, we could have been seriously injured or killed. There were dozens of spots where I could have fallen over 100 feet, and plenty of ledges to strike. Our method was dangerous, but we could have dialed it back at any point. We only climbed as fast as we could safely justify.

Our method was dangerous ... but we only climbed as fast as we could safely justify.Jim Reynolds

Which sections were the toughest for each of you?

BG: The “Boot Flake.” It's super runout—falling there would mean death. Climbing the “Stovelegs” was exhausting, too. It’s steep and sustained, so we couldn’t rest.

JR: “Hard” comes in a few varieties up there: scary stuff, time-consuming stuff, and physical challenges. For me, parts of the “Great Roof,” “Pancake Flake,” and “Glowering Spot” were the most physically demanding. The psychological crux was the “Lynn Hill Traverse.” There was tons of slack in the rope and I hadn’t clipped any gear; it would have been a 150-foot fall.

What did you guys do on top after Brad tagged the tree?

BG: There was no one up there. We just sprawled out for a few minutes without speaking. After a bit, I texted Hans and Honnold—they were psyched. We took a selfie, posted it on Facebook, and hiked back down.

JR: No crying or hugging, but I screamed a bit. And I may have done some dry heaving. I have so much to process before I’ll understand what this experience means to me.

What’s next? Do you think you’ll try to break your own record?

BG: I'm not going to try again—it's really dangerous. I think I'm moving to Las Vegas for the winter to climb in the desert. I want to focus on hard free-climbing. As far as the future, I have a few big-wall free-climbing goals planned.

JR: I don't know what's next, but we won’t break our record. I've descended El Cap so many times … now I'm going to do some mountain biking and safe climbing. I play the mandolin, too. I'm stoked to pour some energy that direction.