How Two Sisters’ Love Helped Them Survive Auschwitz

Lessons in the triumph of love and compassion over intolerance and hate.

On March 26, 1942, in Poprad, Slovakia, 998 women boarded a train. They thought they were going to a work camp. They were on their way to a death camp.

One of those on the first registered Jewish transport to Auschwitz was a 17-year-old Polish girl named Rena Kornreich, who’d been working in Slovakia as a nanny. Two days after she arrived in Auschwitz (where she was the 716th female prisoner registered), her sister, Danka, did too.

For the next three years and 41 days, Rena and Danka endured a host of dehumanizing horrors: starvation, beatings, forced labor, and the constant threat of death. Yet they persevered and survived—a remarkable triumph of love and compassion over intolerance and hate. Rena’s long life ended in 2006, more than 60 years after her liberation.

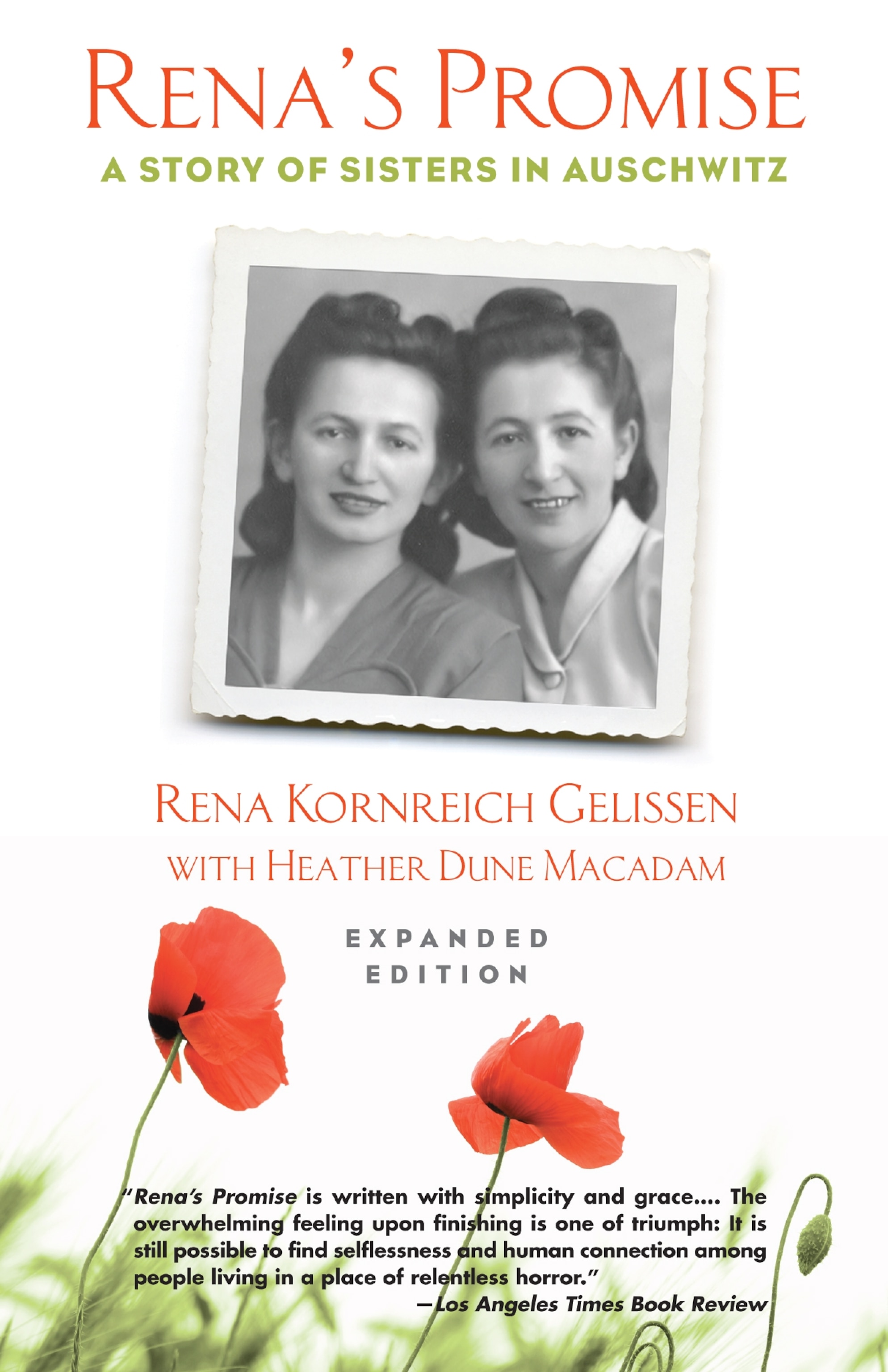

To learn more about this powerful story, and to share it on Holocaust Remembrance Day, National Geographic recently spoke with Heather Dune Macadam, co-author of Rena’s Promise: A Story of Sisters in Auschwitz. First published in 1995, the memoir has just been reissued in a newly expanded edition.

How did you come to be involved with this project? And what compelled you to help tell Rena Kornreich’s story?

I met Rena and it was instant love. We just clicked. She said she’d been telling her story for 50 years in her mind, and she just needed someone to write it all down.

One of our first conversations was on the phone, as I was making dinner. She asked what I was having, and I said pierogies. “Oh,” she said. “Are you Polish?” “No,” I said, “I just like them.” And she said that was a sign from God that I was meant to help her tell her story!

That was in 1992. We met every weekend and wrote the book in three months. It took awhile [to get her to relive her experiences]. She spent a long time trying not to talk about Auschwitz. But I just let her go, and eventually we got into it.

The original idea is that this would be personal—she wanted me to write down [her experience] for her children. But about halfway through I went, “Oh, my God! This is an amazing story. This is a book.” And she said, “I know.”

In the book’s title, what is the promise? And what does it mean beyond this story?

The original promise goes back to Rena’s childhood. Danka was young and fragile, and Rena’s job was to take care of the little one for Mama. When they ended up in Auschwitz, that became a very big job.

The promise itself was made when Danka was losing hope and had stopped eating. “You’re going to make it,” she said to Rena, “and I’m not. And I’m afraid to go to the gas chamber.”

So Rena took her hand and said, “This is the Torah—my hand is the Torah. And in front of God and Mama and Papa, who are standing here in front of us [even though you can’t see them], I swear to you that we will live or die together. If you die, I will die with you. You will not be alone, no matter what.” The next day Danka began to eat again.

After Rena arrived the major transports started arriving. Within a couple of weeks there were 4,760 women in camp, and the Final Solution was under way.

That was the original promise. But in a larger sense, the promise is to bear witness—to take care of each other, to act humanely and with compassion. That’s something I carry in my heart. Others do too. I get lovely responses from readers about carrying on the promise of taking care of each other.

Rena’s relationship with her sister is at the heart of this story. Can you tell us a bit about their childhoods and their Orthodox Jewish upbringing?

Rena and Danka grew up in the Polish village of Tylicz, on the border of Poland and Slovakia. The Jews—there were about 60—and the gentiles there lived together in harmony.

Rena always said that her upbringing informed her perspective. If beggars came by the Kornreich household and were hungry, they were fed. If it was cold out and they had children, they were invited to sleep in the kitchen. Nobody was turned away from that house. It didn’t matter if you were a gypsy or a poor Jew or a poor gentile. And Rena grew up with that ethos. She carried that kindness and generosity with her into Auschwitz.

It was infectious and symbiotic: When Rena was weak, Danka showed up for her sister. And there was a group of girls from Tylicz in Auschwitz. They’d all grown up together, and they helped each other through this ordeal. Amazingly, they all survived.

Rena fell in love with a Russian Orthodox Pole named Andrzej Garbera, who went on to do heroic work in the Polish Underground. Tell us about him and about their relationship.

They met when they were very young. He was Russian Orthodox, and she was an Orthodox Jew. They weren’t supposed to be in love, but they were.

He also saved her life. After an SS man threatened to rape Rena, Andrzej smuggled her into Slovakia. But Andrzej was part of the Polish Resistance, and it was dangerous work. One winter he got pneumonia—and died. He was just 21 or 22. It completely destroyed Rena.

I found his grave when I went to Tylicz. Rena had said that when she went there, an SS man was standing at the gate, staring at her. She couldn’t leave anything [on the grave] because he would shoot her—because a Jew leaving anything on a gentile’s grave would defile it. So she stood there and wept and put her tears on Andrzej’s grave. When I went there I lit a candle and left flowers. I did for her what she always wanted to do. And I wept too.

Readers might wonder how Rena wound up at Auschwitz. Why did she believe that volunteering for a work camp would protect her family from the Nazis?

After she’d been smuggled into Slovakia, she turned herself in because she was an illegal alien. The family she was living with would have been in danger if they were caught hiding her.

The Slovakian government informed Jewish families that they had to give up one daughter to go to a work camp, and that the work would help support the family. Of course, everyone thought “work” meant “farm work”—working in a field and planting potatoes.

If you want to get rid of a race of people, you attack women. Women are the nurturers of a race.

The first four transports out of Slovakia were all women. Prior to that, the camp only had POWs and political prisoners. There were some Jewish men, but they were intelligentsia or Communists; they’d all been arrested for something.

After Rena arrived the major transports started arriving. [The Nazis] were gathering young people for slave labor. Within a couple of weeks there were 4,760 women in camp, and the Final Solution was under way.

The danger and the brutality of the camp come through loud and clear. Fortunately, the other side of humanity—kindness, sisterhood, mercy—comes through as well.

Absolutely. That mercy and that sisterhood—that humanity—is key to survival. You can’t survive if you’re on your own. And I don’t think anyone did.

One of the most amazing stories [involved] the kapo Emma, who was a prostitute. One day Rena was caught committing an infraction and was beaten brutally by an SS man, who said, “Your number is up.” Which meant she was going to the gas chamber.

When everyone marched into the camp for roll call, Emma went into the SS office. When she eventually came out, she looked at Rena and said, “Disappear!” And Rena lived.

I think you can guess what Emma traded for Rena’s life. She protected this girl by giving herself. It’s amazing to me.

Rena and Danka survived in Auschwitz for more than three years. But they had a number of very close calls. Which would you say was the closest?

Probably the incident with Dr. Mengele. It shows how Rena was always hyper-alert. When people would ask her how she survived, Rena would say it was just luck—nothing but luck. But she was street smart. She understood human nature.

So Rena and Danka had been selected for work detail by Dr. Mengele. Now sometimes these work details were actually good. They could get you out of hard labor, even save your life. And of course that’s what [Rena and Danka] were hoping for.

But as they were standing there, they were given clean, pressed new uniforms—with no numbers. That was the first clue [something was wrong]. Then Rena saw an office worker scratch a name off the clipboard she was holding, pull a girl out of line, and take her behind the office. Rena realized at once, “This is a death detail.”

Rena said it best herself: ‘I do not hate. To hate is to let Hitler win.’

Danka was freaking out, saying, “We can’t do this!” But Rena said, “Listen, I’m going to take your hand, and we’re going to walk right across the camp, as if we’re obeying orders. And if they shoot us, well, we were going to be dead anyway.”

And they did it, and they made it! Nobody stopped them. They got back into their old uniforms and they made it back to roll call. They were counted, and they lived.

A few weeks later they learned that all of the women on the Mengele detail had died. It was a sterilization experiment.

How different was the camp for women than for men?

Well, if you want to get rid of a race of people, you attack women. Women are the nurturers of a race. So genocide always targets young women. Always.

A lot of women at Auschwitz were raped. But it wasn’t just a physical rape; it was a visual rape. These young women, most of them virgins, were stripped naked and shaved head to toe each month by Jewish men, while SS men looked on. It was beyond dehumanizing.

For your research you went to Poland and retraced Rena’s journey to Auschwitz. What did that reporting bring to the book? And what did it mean to you?

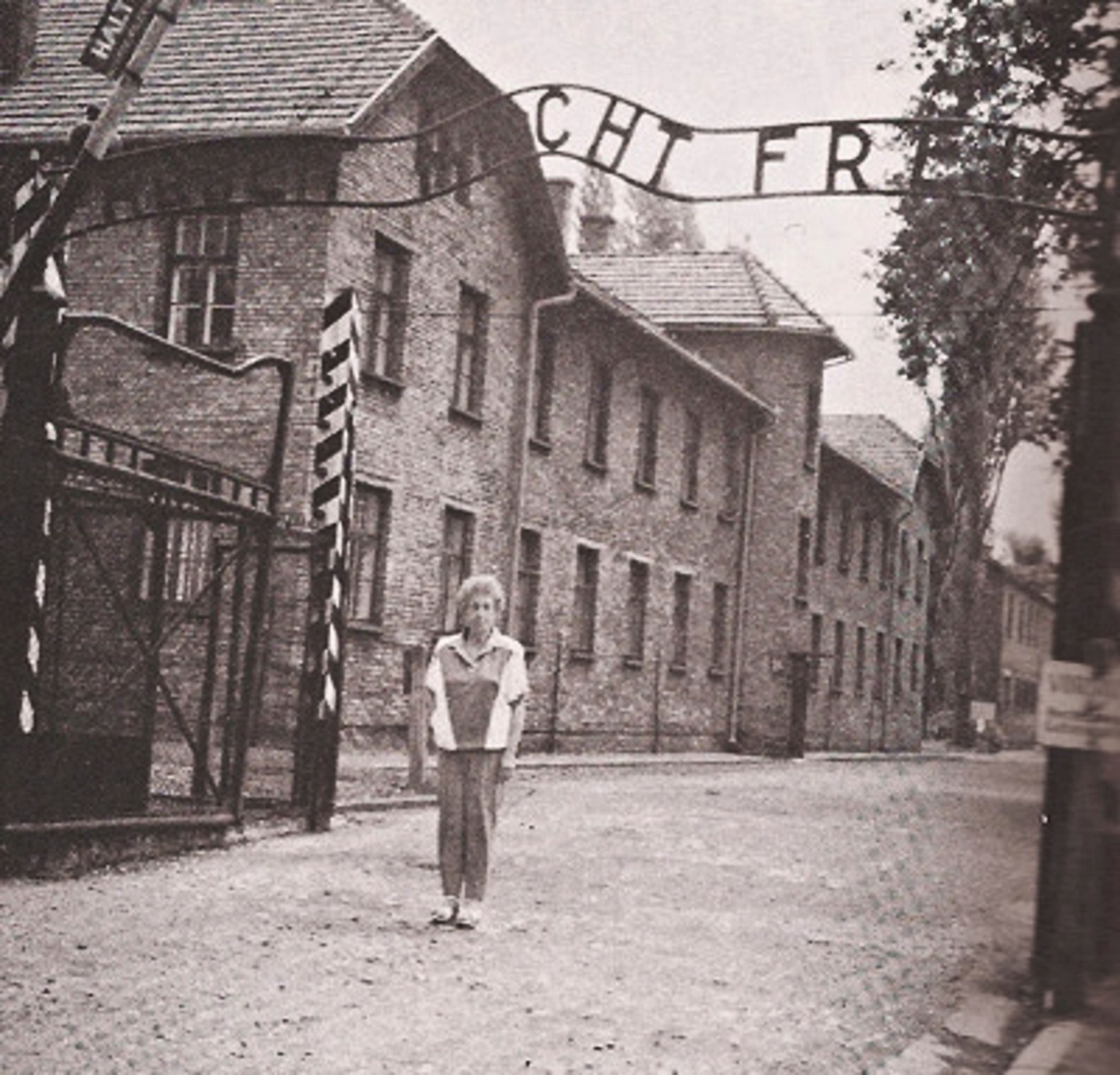

It was incredible. On the 70th anniversary of the first transport—March 26, 2012—I traveled to Poprod, Slovakia, and took a slow train to Auschwitz. When we got there, we went to the first crematorium, said the Kaddish, and lit candles. I don’t know if there are words for it. I felt as though I had done something really important in my life. And I knew that I’d done something important for those 998 women.

This edition of Rena’s Promise is updated and expanded edition. What’s new in the new book?

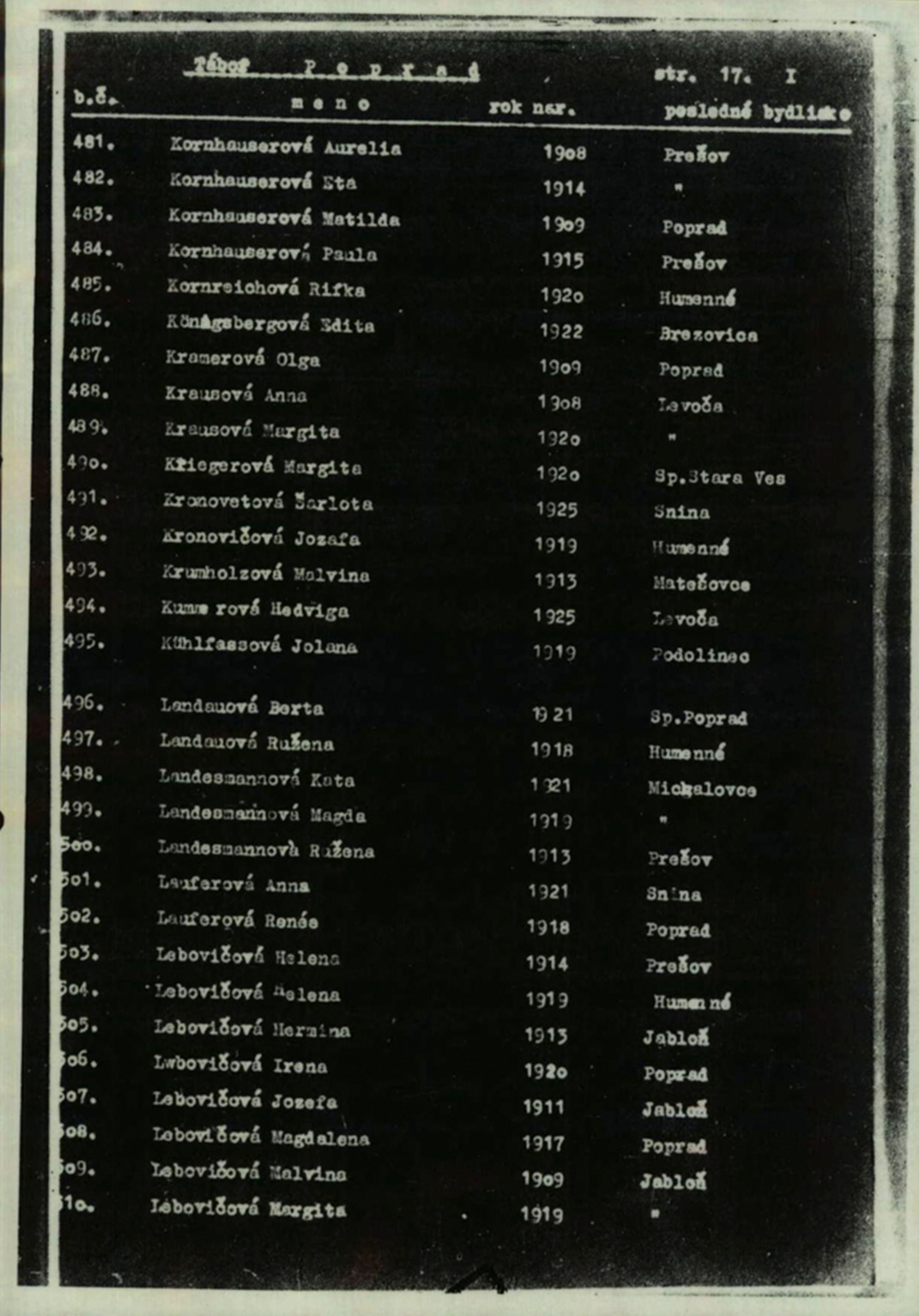

The most exciting thing is that I’ve found the actual original list of the first transport of women to Auschwitz. I compiled it with the help of the USC Shoah Foundation, which had 22 names, and families who contacted me after I set up a forum on our website.

After a few months I got this enormous email from Yad Vashem with the original list: every name of every girl on the first transport, their ages, and where they came from. We now know that there were 297 teenagers on the first transport, and over 50 of them died in the first six months.

Through this research, I’ve also been able to put together a more accurate picture of what happened on the first transport. Because Rena could only tell [the story] from her perspective. I want to make it really clear that this is a tragedy of all young women, and what it was like for all those other families.

The story has a happy ending: Rena and her sister are liberated, they emigrate to the United States, Rena marries a Red Cross worker named John Geliessen, and they have four kids.

Yes, that whole epilogue is new. I’ve changed the beginning too, so it’s a little more clear. I wrote the book in first-person present tense, which is how Rena really told the story. But people are interested in me and my relationship with Rena. So that’s sort of a separate chapter. And then we get into Rena’s story.

One of my favorite stories was when we were doing a lecture, and there were about 800 people in the audience. And Rena, who never wants anyone to be sad, says, “I have a good life and a good husband—and handsome too!” Then she points at her husband, who was sitting in the front row, and says, “Stand up, John! Let everyone see how handsome you are.” And he stands up, and everybody gives him a standing ovation, and he bows to the audience. It was so sweet.

What’s the single most important thing you’d like readers to take away from this book? What would Rena’s message be?

We read Rena’s story and we’re amazed by some of the horrors. But I’m equally amazed how random acts of kindness are also random acts of courage. That’s really important for young people to know.

Rena said it best herself: “I do not hate. To hate is to let Hitler win.” That’s the takeaway—to stand up against hatred, racism, and prejudice. And that is our promise to each other, to humanity and mankind and future generations. That’s what it’s about.