New Smithsonian Museum Confronts Race 'to Make America Better'

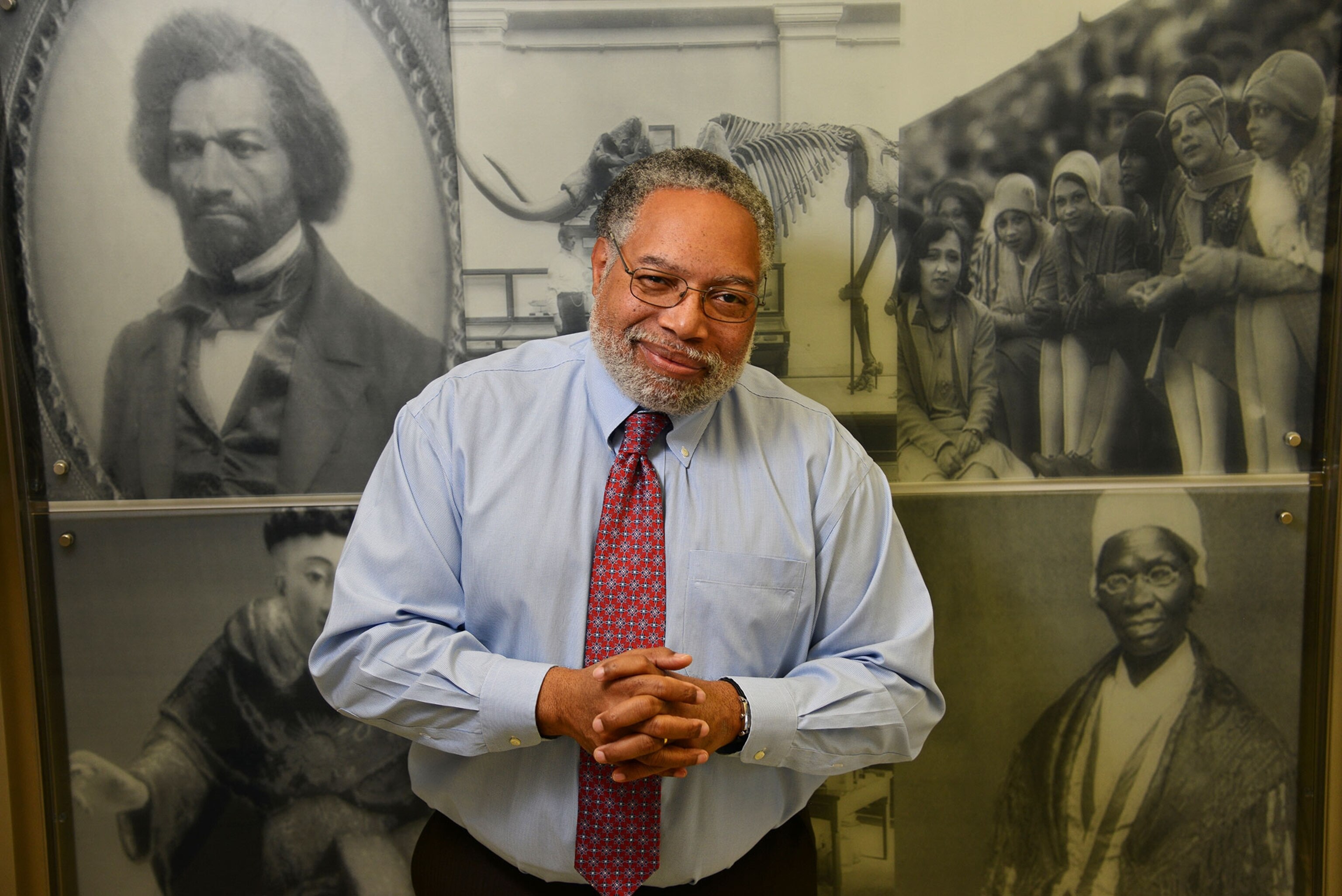

Writer Michele Norris and the museum’s director, Lonnie Bunch, talk about his vision for teaching Americans about their tortured history.

From the minute he signed on to become director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2005, Lonnie Bunch has sought to redefine the idea of a Smithsonian Institution museum. His effort is evidenced in the design of the building, which is aggressively unconventional. It is evidenced in the way the museum built its collection, bypassing the traditional curatorial route to cull treasures from everyday people in a series of events styled like Antiques Roadshow. And it is evidenced in the museum’s core mission, to take an unflinching look at the darkest chapters in American history with the full expectation that visitors will be pushed beyond their comfort zone.

In working on an article for National Geographic magazine about the new museum, which opens Saturday, September 24, Michele Norris conducted a series of interviews with Bunch. What follows is an excerpt from one of those conversations. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Michele Norris: So with this new museum, it’s more than just creating a new museum. You’re trying to introduce a new way of thinking about history and culture, in part to the Smithsonian Institution and in part to America.

Lonnie Bunch: Yes. Part of what I wanted to do with this museum is recognize that we have an opportunity—partly because of the era, partly because of the technology, partly because it’s the Smithsonian—we have the opportunity not just to make a good museum, but to craft an institution that is as much about today and tomorrow as it is about yesterday. Well, I thought, let’s be explicit about it. Let’s talk about how understanding race, understanding our tortured history can help us with the world we live in today. And so my goal was to, yes, be a very good museum, be the best museum we could be, but that wasn’t enough. Our job is ultimately to create spaces, to create programs, to create opportunities to make America better.

Norris: Has the Smithsonian and have museums in general dealt with race in the way that they should? If you don’t understand race, if you don’t examine race, it’s impossible to truly understand America. Have we done a good job?

Bunch: When I first began my career, race was something most museums didn’t want to talk about, right? And then as there was a desire to reach out to new audiences, to respond to scholarship, to respond to some of the funders, people began to explore African-American culture and Native American culture in a way that marginalized it, that said this is an important story, but it’s an important story for a particular community. It’s not our story. So part of what I wanted to do was to say that when the Indian Museum opened, the Indian Museum’s goal was to make sure that native peoples knew their story, felt good about their story, and if others benefited, so be it. I argue that because of 50 years of scholarship, because of the importance of African-American culture that, in essence, I needed to say this was everybody’s story. There may be people who own the story, who live the story. But all of us, regardless of race, regardless of how long they’ve been in the country, were shaped by it in profound ways.

Norris: So what do you say to critics who will say, well, if race and if the story of African Americans in America is integral to understanding America, why build a separate museum?

Bunch: In some ways I would argue that this is much like Civil War battle sites. Each battle site is different, but it may tell you something about the Civil War. But if they do their job right, they tell you to look at it in a very different way. And I would argue that the story of the African American, especially the way we’re framing it, it’s too big to be an ancillary story in part of a small museum. Every museum in America should wrestle with questions of race. But not every museum has the space, and the expertise, the scholars, to be able to explore the complexity, the nuance, the sweep that we’re able to do.

Norris: So in that sense, this museum is a little bit different than say the Holocaust Museum, which also has a very deep and rich experience where you sort of can’t escape the pain of that history. This will have moments of joy, and moments of triumph, and moments of surprise. But I wonder if the opening and the response to the Holocaust Museum was something that you studied in trying to figure out how to create the right balance in the exhibits and in the experience at this museum.

Bunch: I think the Holocaust Museum did the best job of any museum I had ever seen up until that point that really explored difficult moments in a way that the public didn’t shut down. So I thought there was a lot we could learn from them. But I also realized that this was a very different experience—that the Holocaust Museum had one benefit that we don’t have. In the Holocaust Museum the bad guys weren’t American.

Norris: They weren’t people’s relatives.

Bunch: No, and so basically our challenge was how do we help Americans come to grips with their own history, with their own culpability? And so early on I talked to futurists, I talked to educational psychologists, I talked to anybody who would listen: Just help me understand what are the ways you help people? And so part of what was really clear was that you had to find the right tension between pain and resiliency, between moments of tears and moments of joy. There are moments where you’re going to say, oh, my God, but there are moments where you’re going to smile, or you’re going to find ways to sort of accept the difficult moments.

Michele Norris hosted NPR’s All Things Considered for more than a decade. She is founding director of the Race Card Project and author of The Grace of Silence, a memoir examining hidden racial legacies. She wrote about the museum for National Geographic's October 2016 issue. Follow her on Twitter.