Health workers are exhausted. A photo studio let them express it.

Staff at this hospital in Belgium managed three pandemic waves with hardly a moment to rest—then they reached a breaking point.

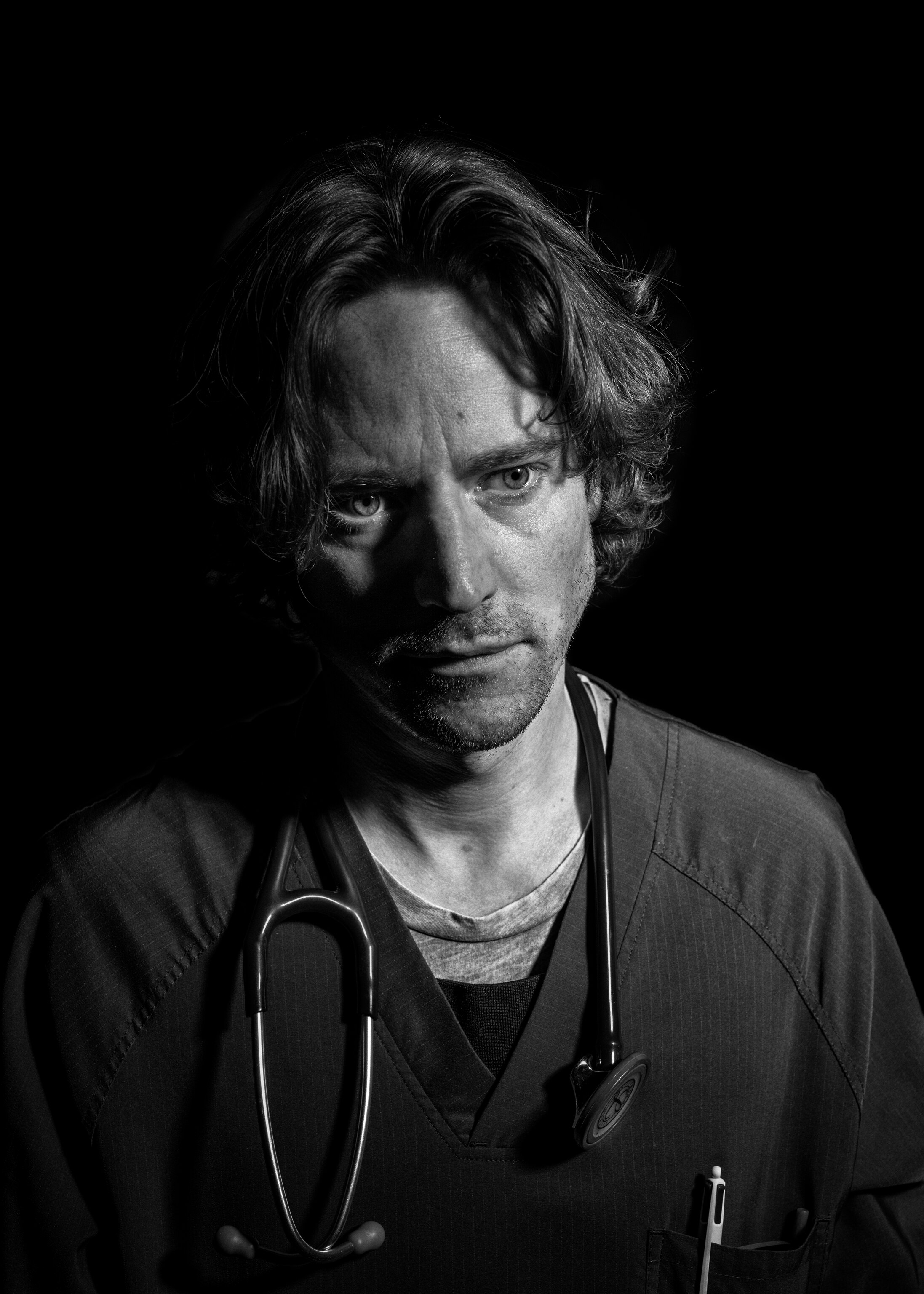

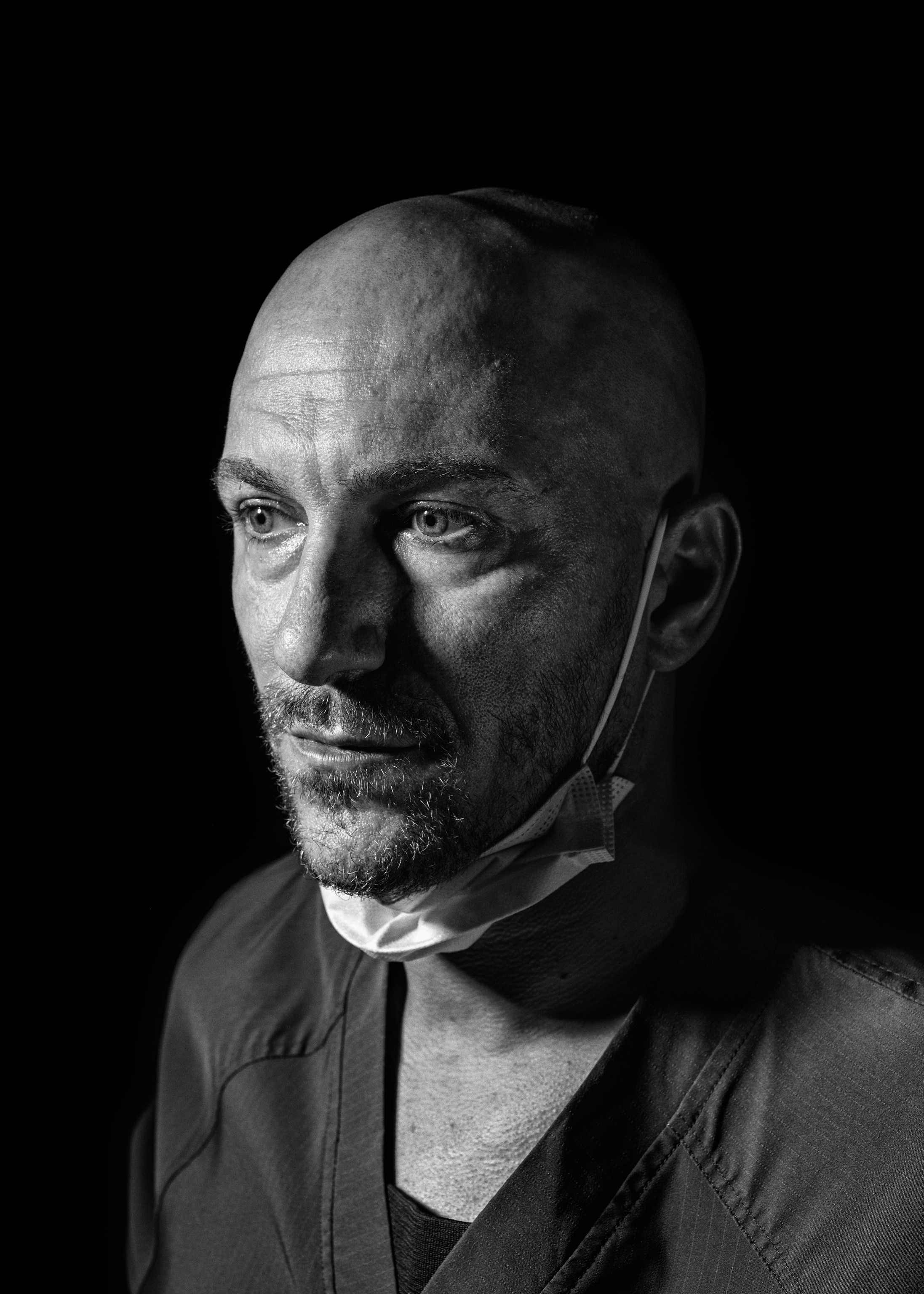

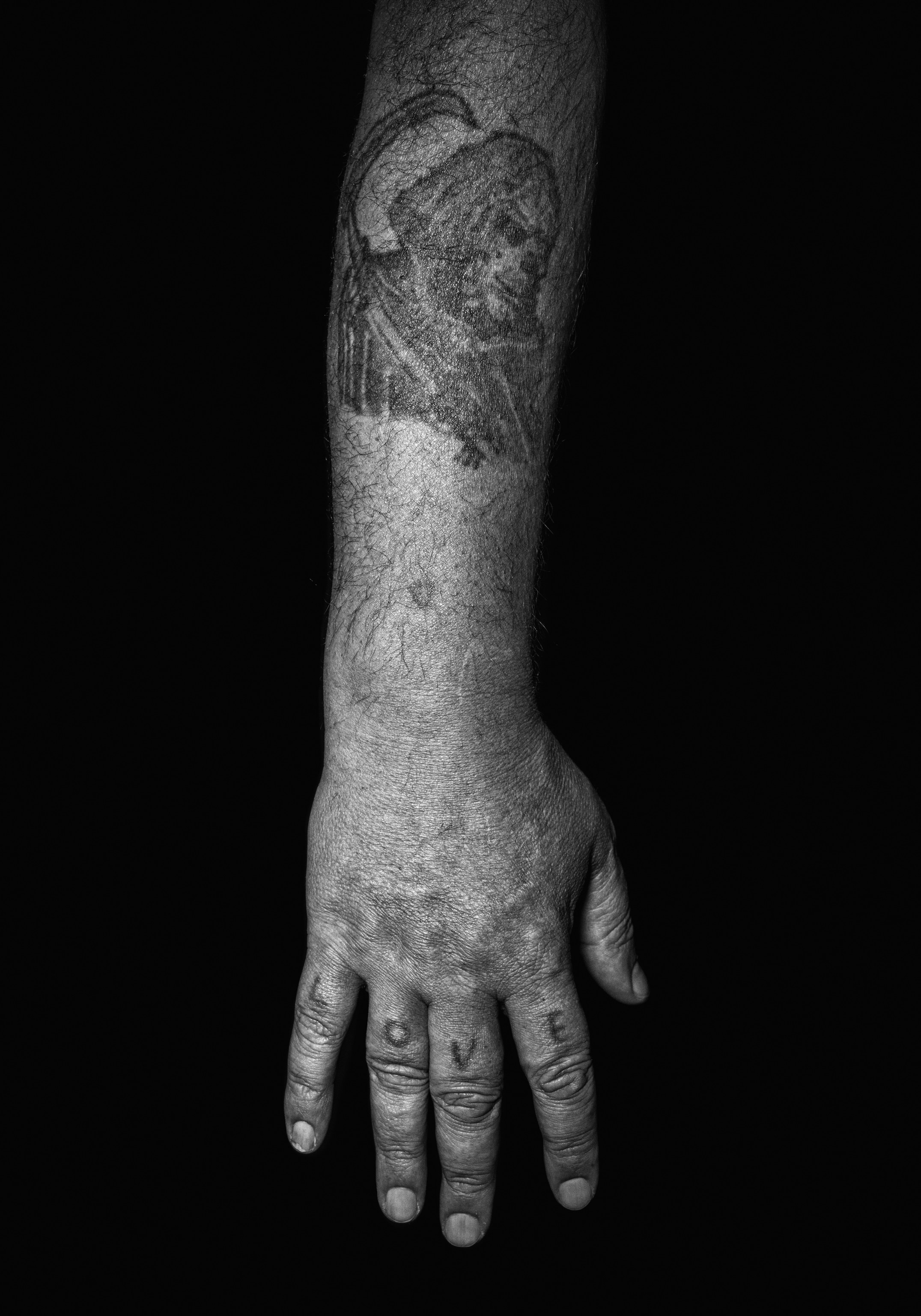

Six months ago, thick paper was taped to the windows of an 11th floor office in a hospital in the Belgian city of La Louvière. With the summer light blocked, a dark backdrop was hung inside the office and a camera positioned in front of it. From a laptop, mournful cello and piano notes filled the room. Over five days, around 60 workers at the Tivoli University Hospital—from janitors to ambulance crews—trickled in, pulled down their masks and let 16 months of pandemic exhaustion flood their faces.

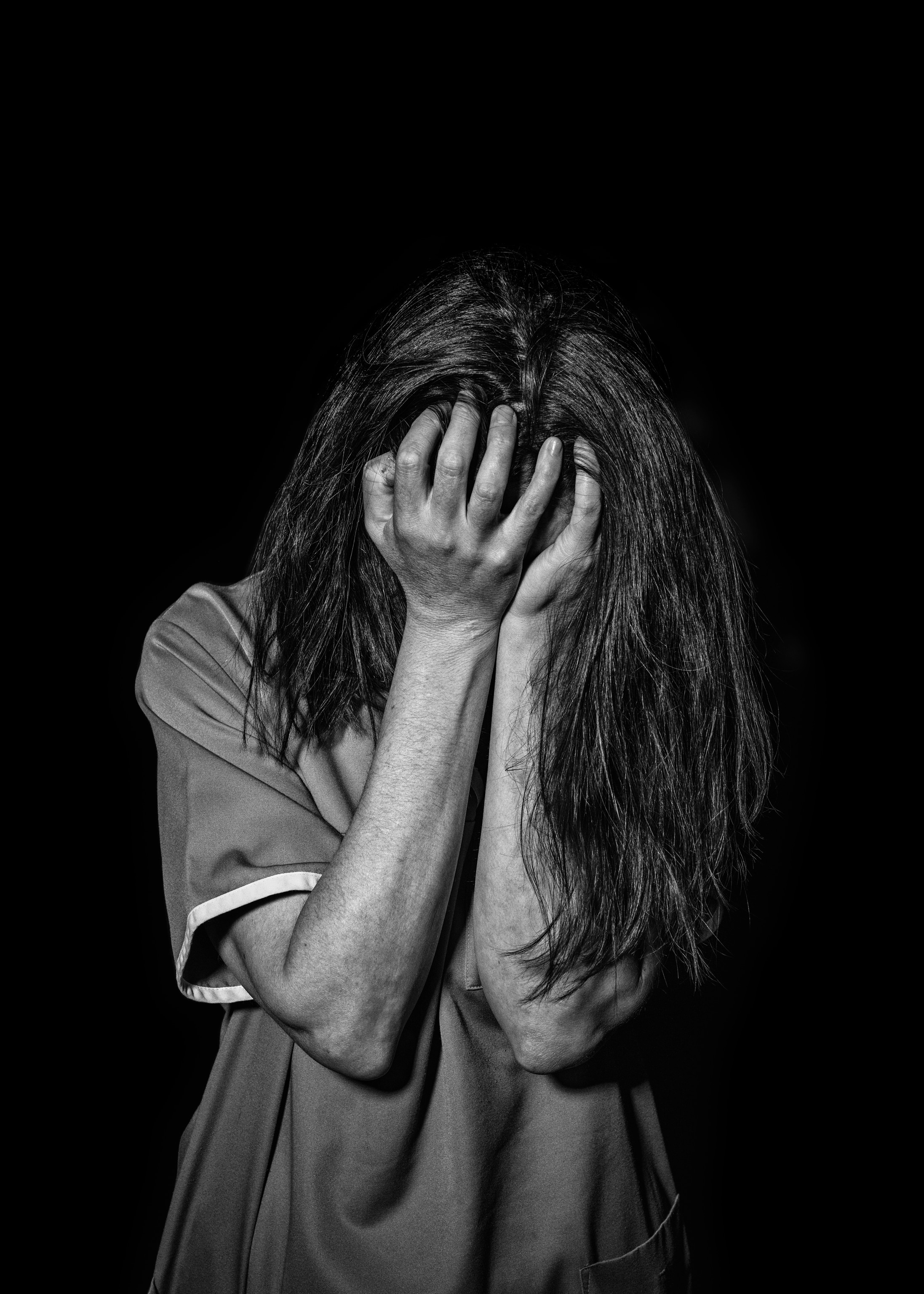

Many of the subjects cried, some even before the camera was raised. Others fell to the floor. Sometimes the photographer, Cédric Gerbehaye, moved from behind the viewfinder to hold them in his arms and comfort them.

The fear, sadness, and anger that boiled over in these sessions had, for some, been hidden from friends and family, even themselves. “During these sessions they could release,” says Gerbehaye. “They could just be present for themselves, with nobody to take care of, no colleagues to help or support, no family member to reassure—no one, just them.”

Gerbehaye arrived in La Louvière in April 2020 from his hometown of Brussels. Like many places, this city of steel manufacturing and coal mining also was battling a rising number of COVID-19 cases. Gerbehaye, who was granted full access to the city’s frontline services by the mayor, began creating a historic archive of the pandemic through hospital workers’ eyes.

During the first wave that spring, ICU staff would spend their entire shifts on the floor, without eating, drinking, or using the bathroom. They sweated profusely under their protective equipment. By the second wave, they were ready: they had more skills to tackle a previously mysterious disease. They strapped cool packs on their bodies to help cool them down.

That wave had been difficult, but by July 2021, the city was emerging from a third wave of COVID-19 infections. Gerbehaye had been documenting the Tivoli hospital and its staff over 15 months and three waves. The fatigue this time was different: workers were tired, sick, and disillusioned. Some were haunted by the earlier waves. Many had to call out sick from work. “That’s when you could feel the fault line,” says Gerbehaye.

A bed in the ICU requires 12 hospital staff members to monitor the machines and care for the patient over the course of 24 hours. By the third wave, absences meant that sometimes these jobs were stretched between eight staffers.

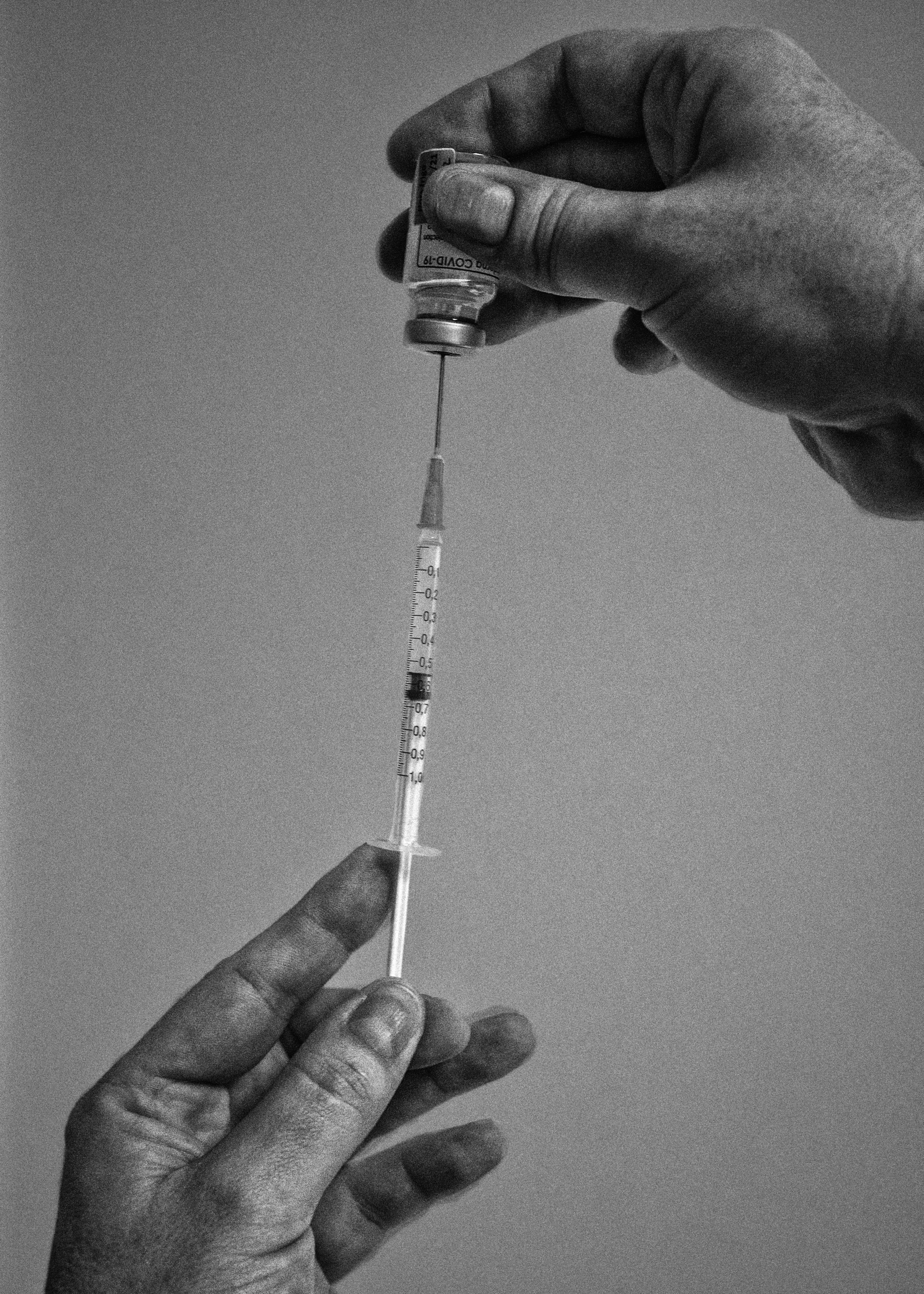

By last summer, around half the population of Belgium was fully vaccinated, but rumors and conspiracy theories had taken hold. A year before, health workers had been publicly applauded every evening at 8. Now, they felt like society had disregarded them by flaunting mask mandates and refusing vaccinations, and politicians hadn't been recognizing their efforts. “By the end of the third wave, I could feel that some of them lost faith,” Gerbehaye says. “Not in what they were doing, but in consideration people had for them.”

In French, they say, “La goutte d’eau qui fait déborder le vase”—the drop of water that makes the vase overflow. Healthcare workers at this hospital had managed three waves of COVID-19 cases, hardly able to steal a moment of rest. Now they were at a breaking point.

During the week-long portrait session last summer one staffer from the emergency room and intensive care unit told Gerbehaye he was considering quitting, after nearly two decades of hospital work, to become a train conductor. “What the pandemic did above all,” Gerbehaye says, is “show what our limits are.”

“After a third wave, how can you do it when your body doesn't have the energy anymore? You are sick, you are tired, you suffer from PTSD. All this was, in a way, what was released when I photographed them.”

The portrait studio was a form of catharsis for the workers and also for Gerbehaye. He, too, felt a release in that week-long span, and prepared to say goodbye to a place where he’d made some of the most emotional work of his career. He’d turn those portraits, along with his earlier work, into a book called Zoonose with writer Caroline Lamarche, and a local exhibit. “I am not the same person anymore,” says Gerbehaye. “It is a work that has changed me.”

Cédric Gerbehaye is a Belgian documentary photographer and a founding member of MAPS Agency. He is the author of the books Congo in Limbo (2010), Land of Cush (2013) Sète#13 (2013), D’entre eux (2015) and Zoonose more recently. His work received several international recognitions (The Olivier Rebbot Award from the Overseas Press Club of America, a World Press Photo, and the Amnesty International Media Award Images by Gerbehaye are to be found in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Musée de la Photographie in Charleroi, Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris and the FotoMuseum in Antwerp.