The Book of Kells might not be Irish after all

The text is a mysterious medieval marvel. A new book claims to know its true origin.

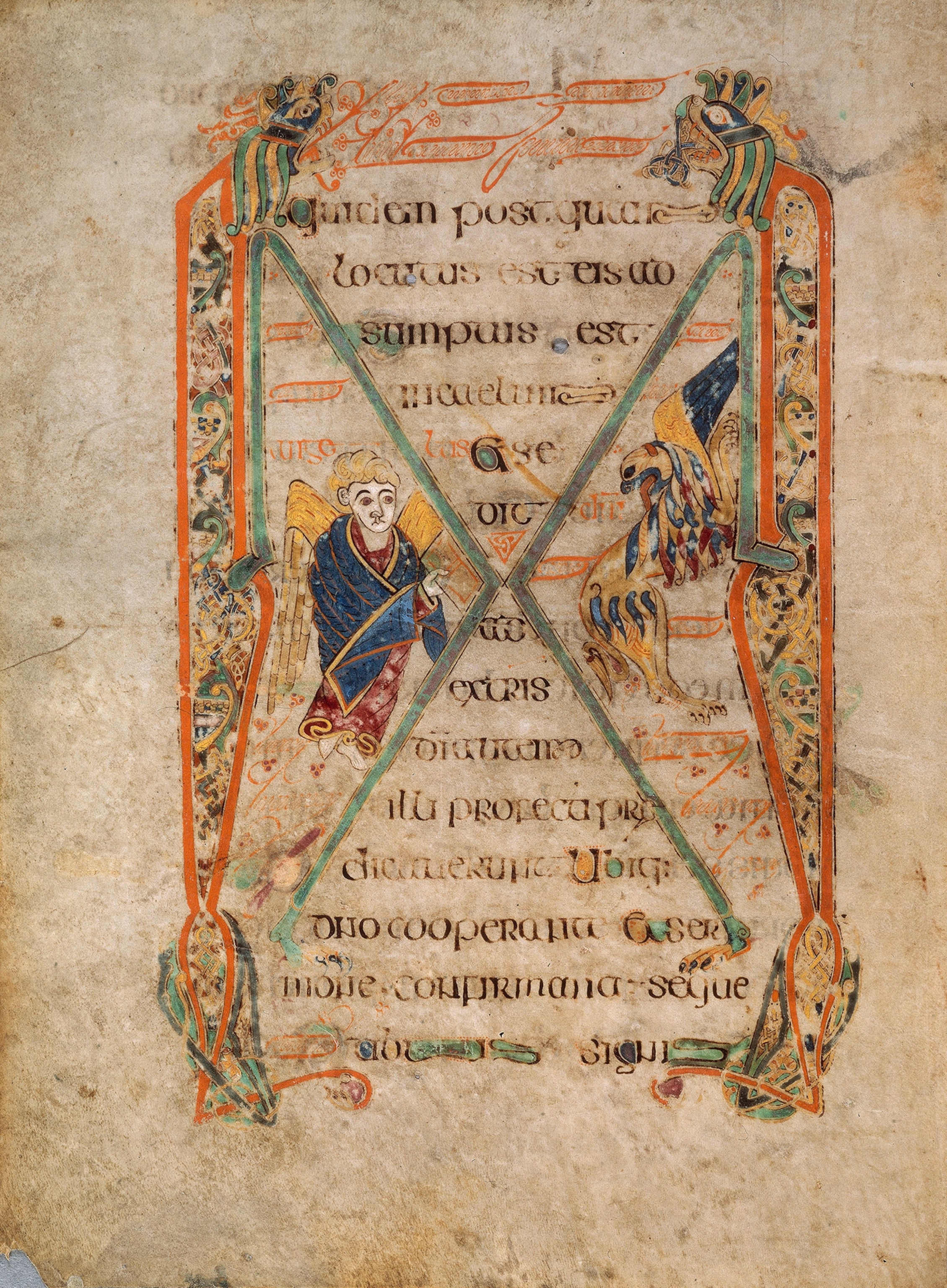

The Book of Kells—an illuminated manuscript of the Christian gospels, the New Testament books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, created c. A.D. 800—may be the world’s most famous medieval manuscript.

On its pages, a veritable menagerie is set loose: sinuous letters resolving into cats and human heads; solemn-faced apostles peering out from nests of impossibly complex Celtic knotwork; chickens and wolves tiptoeing through the text. Words and letters bloom into layer upon layer of ornament. Each of these images, often smaller than a quarter, is rendered with astonishing precision, especially considering the creators were working long before the invention of the modern magnifying glass. Its 680 pages represent the enormous amount of labor it would have taken to produce the book.

Held at Trinity College Dublin, the Book of Kells draws hundreds of thousands of visitors yearly, equally interested in its intricately rendered pages as they are in its mysterious history. Before the Book of Kells was relocated to Dublin in the 17th century, it was held at a monastery at Kells, in County Meath, on the eastern side of Ireland, where it stayed for centuries. Despite its name, it wasn’t made at Kells. The tantalizing question is where it was made, a debate that has recently been reopen by Victoria Whitworth, author of the recently released The Book of Kells: Unlocking the Enigma.

The Book of Kells first appeared in the historical record in the 11th century, it was produced centuries before, a product of the long-lost world of early Christian monastic culture. And the precise origin and identity of its creators remain an irresistible historical puzzle. When the Kells monastery was dissolved in the 16th century by King Henry VIII, the illuminated manuscript was kept safe by the local community until it was moved to Trinity College for safekeeping. In the 19th century, amid a snowballing movement for independent Irish nationhood, the book was elevated into a symbol of Irish cultural identity, a powerful testimony to the island’s rich, sophisticated, and distinctive history.

But the illuminated manuscript might not be Irish at all, at least according to Whitworth. She provocatively argues that it may have originated in the Pictish territory of eastern Scotland—created by a mysterious tribe of Britons so fierce they intimidated the implacable Roman Empire, before becoming a thriving kingdom in early medieval Scotland and then disappearing, leaving only traces in the historical record.

“I feel it’s certainly high time that we stirred up the mud at the bottom of the pond, as it were, and got people to start asking new questions about this most extraordinary book,” Whitworth says.

If Whitworth’s theory is correct, it would be a revelatory discovery: due to cultural and religious upheavals over the centuries like the Scottish Reformation, not a single identifiable manuscript has survived from the once-powerful Pictish kingdom. She draws particular attention to their work in another medium: carved stone slabs, which have long fascinated observers and bear a marked resemblance to the art of the Book of Kells. But Whitworth's theory is contentious even though the academic debate about Kells's origin is far from settled.

(What was Britain like before the Roman conquest? A new hoard of treasures gives us clues.)

The debate about the Book of Kells’s origin

The Book of Kells survived the ravages of time, invasion, and political upheaval because it was seen as uniquely precious. The anonymous medieval monks who labored over the book for hours, creating its detailed, sometimes whimsical illustrations, no doubt considered it special. And for monks at Kells who kept the book for centuries, it was a holy object meant to be venerated.

It dates from when Ireland was rich in thriving, sophisticated monastic communities that maintained strong connections to mainland Europe, often sending monks to continental Christian centers like Saint Gallen in Switzerland. But there was trouble on the horizon, as Vikings began brutal raids along the coasts of Britain and Ireland in the late eighth century, often targeting monasteries as ripe pickings. The Book of Kells itself is a material witness to that violence. It survived at least one brush with oblivion: The Annals of Ulster, an important record of medieval Ireland, reports a theft of the monastery of Kells's great gospel book in 1007. While the book was recovered—under a sod, apparently, stripped of its gold binding—scholars suspect that’s when its original front and back and any clues they held to its origins were lost forever to posterity.

At Kells, we know that the manuscript was treated as a relic of the sixth century Irish Saint Columba who is believed to have spread Christianity across Scotland and northern England. Despite its venerated status at the monastery, scholars agree that the Book of Kells was not created there. For one, the dates don’t line up: Kells wasn’t founded until 807 and took time to grow into the kind of flourishing monastery that could produce an illuminated manuscript as sophisticated as the book. And stylistic analysis suggests the manuscript is older, says Rachel Moss, a professor of medieval art and architecture at Trinity College Dublin.

The consensus candidate is the deeply influential and politically powerful monastery on the island of Iona in the Scottish Hebrides founded by Columba himself in the sixth century. By the eighth century, Iona would have been part of a cultural sphere that encompassed much of the north of Ireland as well as the Hebrides and Argyllshire in modern-day western Scotland, unified by a similar dialect of Gaelic and knitted together by the surrounding ocean. The monastery at Kells was founded by monks from Iona and the two communities were closely linked.

Iona was a sophisticated powerhouse, a crucial outpost for the spread of Christianity across the region. And it was certainly capable of producing the manuscript: “We know that they had a scriptorium there, because there are other manuscripts that we can very securely place there,” says Moss. One such example is a life of Saint Columba, dating from the early eighth century, which survives today in Schaffhausen, Switzerland (that book curiously contains the first reference to the Loch Ness monster).

Iona, Moss says, was a “place of artistic production” that included leatherwork, glassworking, and metalworking. The monks at Iona were also prolific stone carvers and made stone crosses from around the same time as the Book of Kells. The iconography of those crosses is important because, like the Book of Kells, they include imagery of the Virgin Mary: “That’s significant, because the cult of Mary was only just beginning to reach northwestern Europe at the time,” says Moss.

But the monastery faltered in the early ninth century, as it came under increasing pressure from Viking raids: In 806, for example, 68 monks were slaughtered in a single raid. The monks began transferring relics to Kells, but it’s not clear whether the book was among them.

While the case that the Book of Kells was made at Iona is strong, it’s circumstantial. That’s because researchers are hard up against the simple material realities of illuminated manuscripts. Unlike huge stone structures anchored for a millennium to one churchyard, books are purposefully portable and were easily swapped between closely connected Columban communities.

It's this lingering question mark around the Book of Kells’s origin that prompted Whitworth to take another look. “I thought it would be an interesting exercise if we looked at the great monasteries that have been suggested as a point of origin of the Book of Kells, or as the great intellectual powerhouses of the eighth century, purely from a kind of archeological point of view.”

The case for Scotland

Whitworth thinks it’s unlikely that the Book of Kells was created at Iona because other manuscripts that survive from the monastery aren’t nearly as elaborate as Kells. Consider the eighth-century life of Saint Columba that survives in Switzerland, a manuscript that we know with certainty was made at Iona. Compared to the book of Kells, the life of Saint Columba is unadorned.

“It is the plainest, clearest, most sensible manuscript you can imagine,” she says, contrasting it to the detailed artistry of Kells. “I find it really hard to think that scriptorium, unless there was a complete revolution of ideology […] produced the Book of Kells.”

She also considers the evidence for another powerful and important medieval monastery: Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, off the eastern coast of northern England. Their scriptorium produced the Lindisfarne Gospels, an iconic illuminated manuscript created around 700 and now held at the British Library. Though the Lindisfarne Gospels is a lavishly illustrated book, Whitworth doesn’t think it’s a match to the Book of Kells, largely because it hews less strictly to the Vulgate version of gospels, a fifth-century retranslation from the Greek produced by Saint Jerome.

Whitworth points instead to a monastery in what’s now Portmahomack, situated on a peninsula in eastern Scotland that juts out into the North Sea. In the early medieval era, when the Book of Kells was produced, that territory was controlled by the enigmatic Picts. Historians know little about the Picts outside of Roman writing about the British tribe. The Romans depicted them as warring barbarians covered with paint or tattoos. But they were intimidating even to the great conquerors from the Mediterranean: ultimately, under the reign of the emperor Hadrian, the Romans built an enormous wall stretching across what’s now northern England, to keep them out of Rome’s territory.

Modern archeology reveals a complex culture, however, capable of producing stunning silverwork, for instance, and they were a powerful force in northern Britain in the early Middle Ages after Rome receded. The Picts dominated large swaths of Scotland in the first millennium A.D.—Saint Columba is credited with their conversion to Christianity—but their language was gradually supplanted by Gaelic and none of their manuscripts have survived. That’s probably thanks in no small part to the violence of Scotland’s Reformation in the 16th century: “We know that at many great Scottish churches there were literally bonfires of the libraries,” points out Whitworth.

What has survived from the Picts are enormous stone slabs, carved with intricate knotwork. Those slabs, according to Whitworth, bear a striking resemblance to the Book of Kells. In one particularly endearing example, there are two mermen depicted in Luke echoed by mermen carved into stones at a Pictish royal site in Perthshire. Whitworth isn’t the first to notice the similarities to the Book of Kells: scholar Isabel Henderson pointed them out in the 1980s, writing that “a significant number of varied, specific, traits of composition and decoration” are common to both Pictish art and the Book of Kells.

Despite the similarities, there was little evidence to support manuscript production until recently, after the first excavations at a Pictish monastery located in modern-day Portmahomack, conducted between 1994 and 2015. Led by Martin Carver of the University of York, famous for his work on the Sutton Hoo ship burial, the dig found ample evidence of vellum production: tanks for soaking skins, a specialist knife for scraping them, and pegs to stretch them out. In fact, in the same area, they even found a sculptor’s chisel. That, Whitworth says, “suggests that the monks who are making the sculpture and the monks who are making the books are either very close collaborators or even the same personnel.”

(These manuscripts brought the fantastic beasts of the Middle Ages to life.)

An unsolvable mystery

It’s nearly impossible to prove where the Book of Kells originated. “The trouble with the Book of Kells is it is kind of a closed system,” says Whitworth. “We can really only answer questions about it from it.” It’s even possible the book was created somewhere other than Iona, Lindisfarne, or Portmahomack—perhaps even a monastery on the Irish mainland, which Moss points out have been less thoroughly excavated than somewhere like Scotland, because many of them remain active burial sites.

Scientific advances have helped unlock some of the book’s secrets, but those are also limited to what the book can tell us about itself. In 2009, for example, scientists discovered that the vivid blues in the book were not made from lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan but made from a humbler combination of chalk and woad that had fooled observers for centuries. What is clear, though, is that the Book of Kells emerged out of a rich intellectual and artistic world, populated by people who knew clever ways to fake lapis lazuli, capable of painstaking attention to detail. Its existence, and the debate over its origin, is a testament to a sophisticated cultural network.