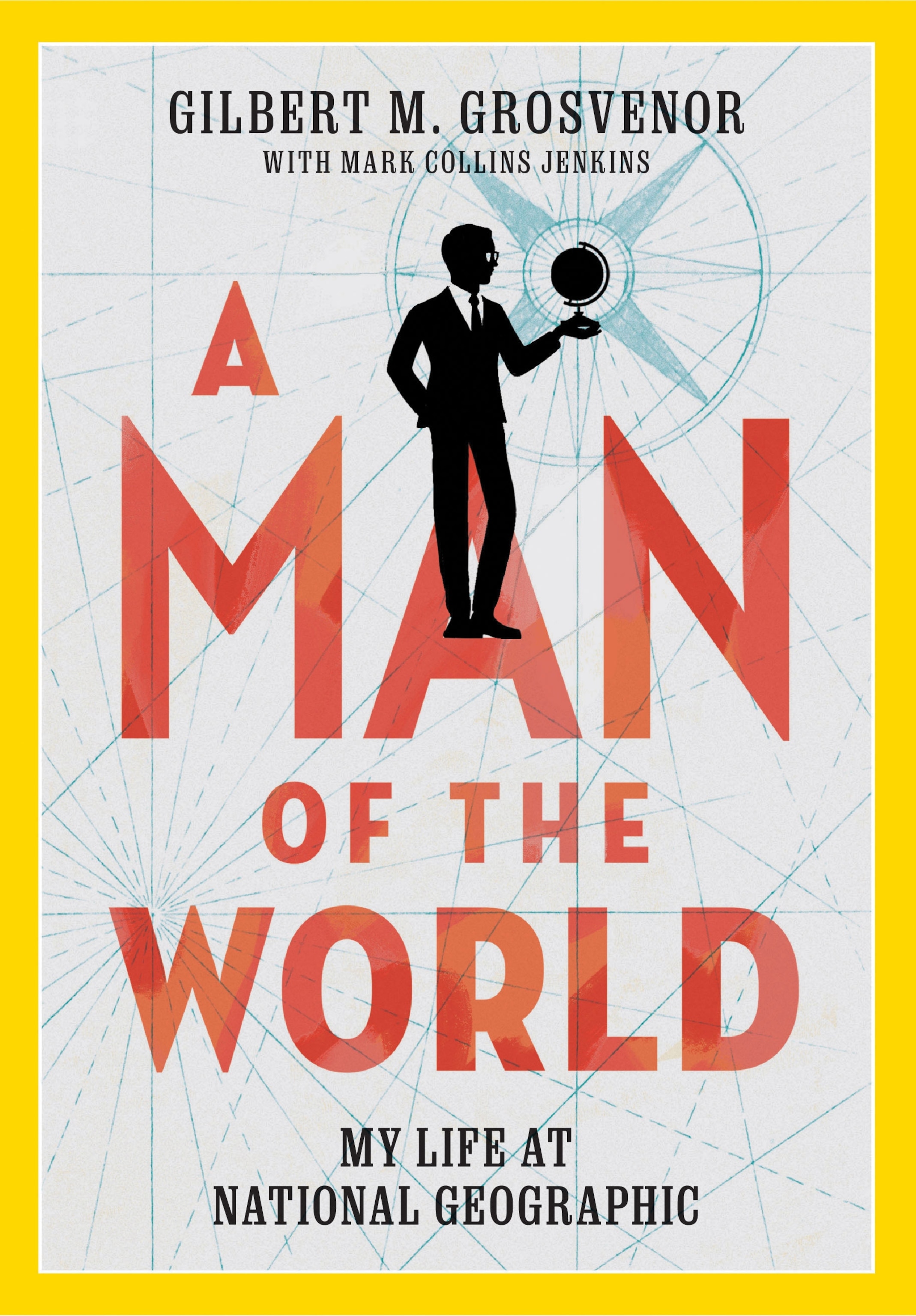

New memoir tells the inside story of National Geographic's founding family

Retired president and chairman Gilbert M. Grosvenor, now 91, had a front-row seat to audacious feats of exploration.

When Gilbert M. Grosvenor retired as chairman of the National Geographic Society in 2010, ending five successive generations and 122 years of family stewardship, he was characteristically modest. “I’ve done my thing,” he said. “It’s time for others to have their turn.”

Despite the privilege of an Ivy League education and a summer home on an estate in Nova Scotia that belonged to his great-grandfather Alexander Graham Bell, Grosvenor kept a low-key profile. He once took a peanut butter and jelly sandwich on a plane and wore, a journalist wrote, “ostentatiously inexpensive suits.”

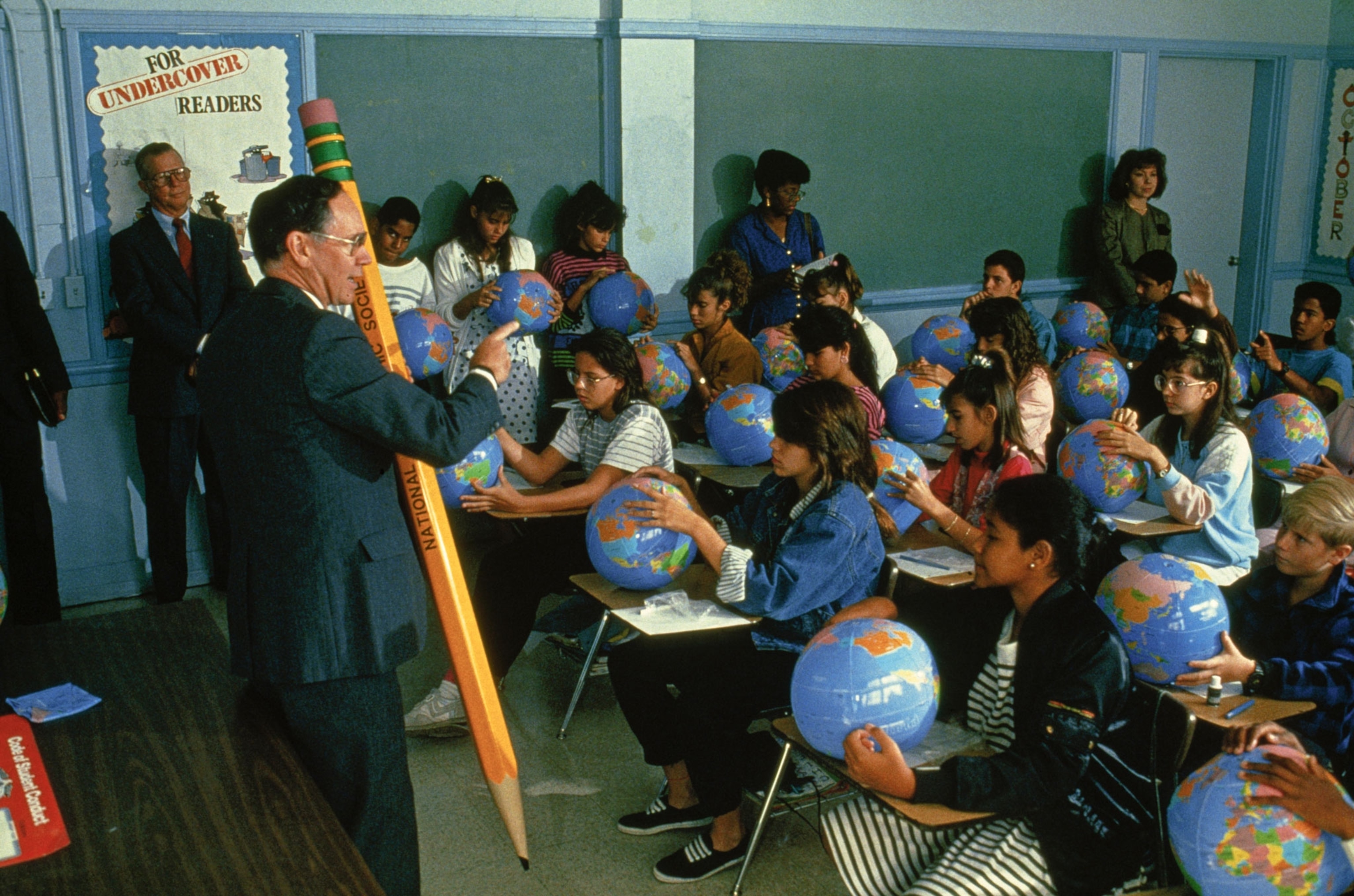

But the understated persona belies the contributions of a man and family who helped make National Geographic the iconic, multimedia empire it is today. The organization founded in 1888 “for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge” would, during Grosvenor’s tenure, expand into television, film, books, children’s publications, and digital media. It would also extend its reach to foreign-language readers and restore geography education to American classrooms—an achievement for which Grosvenor was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In his new memoir, A Man of the World, Grosvenor, now 91, explains what it was like to grow up in the family business that was National Geographic, and why the Society’s mission is more important than ever. Grosvenor spoke by telephone from his lakeside cabin in Nova Scotia. The interview is edited and condensed for clarity.

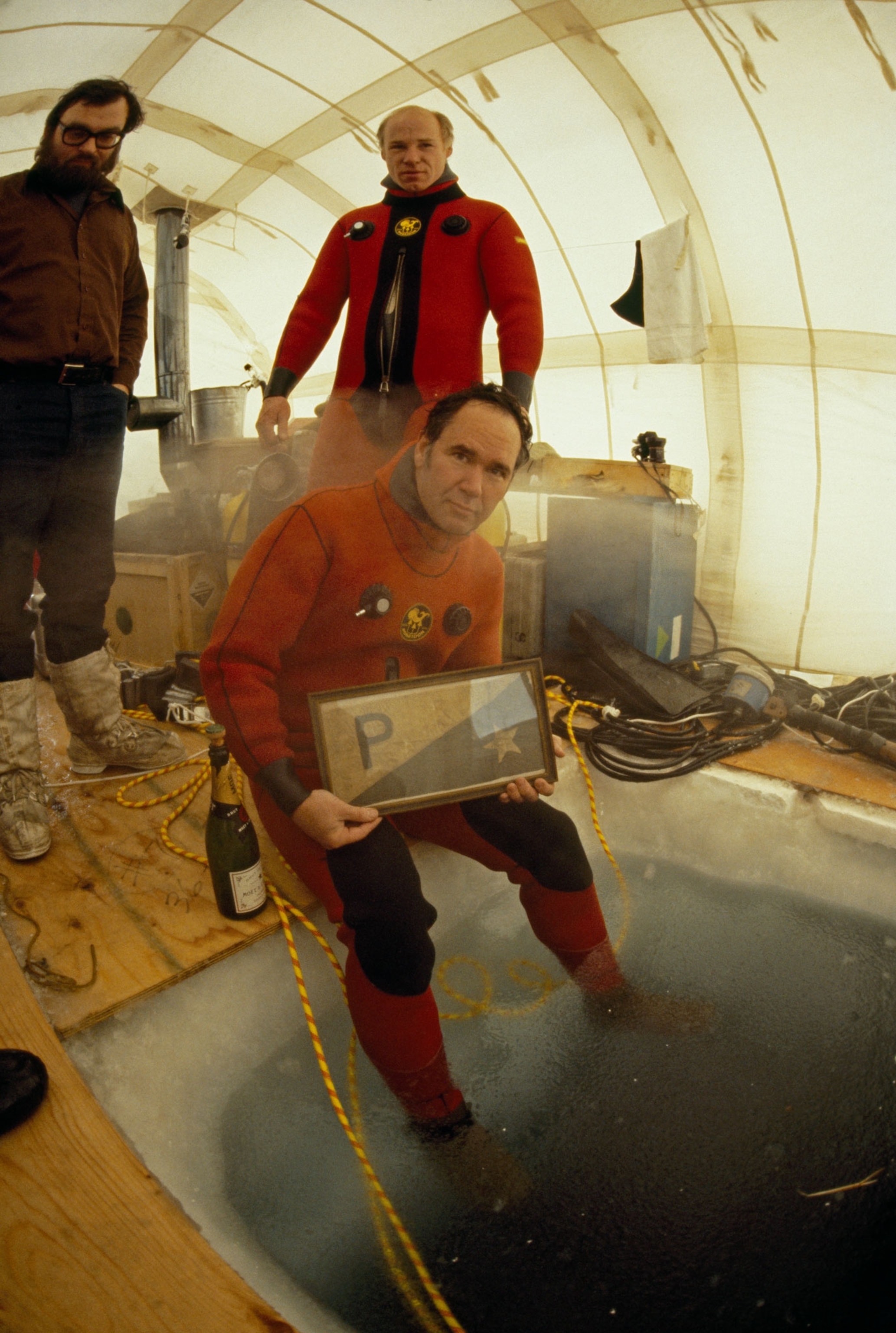

You grew up in a home where everyone from polar explorer Robert Peary to Amelia Earhart to Louis Leakey crossed the threshold. Your great-grandfather, Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, was a Society founder. The press called your grandparents [Gilbert H. and Elsie Bell Grosvenor] “Mr. and Mrs. Geography.” Was being a Grosvenor a burden?

Yes. I was driven by a fear of failure and couldn’t tolerate the thought of not succeeding. In the early days of my career, when I was a photographer for the magazine, I knew every time I was taking a picture, everyone was watching.

Let’s talk about your pre-Geographic life. Ironically, you took a geography course at Yale.

It was awful. How many bananas did Brazil export last year? That was geography then, so I dropped it.

Your original career path was medicine, but your life took a turn.

Between my junior and senior year, I went to the Netherlands as part of a program to help repair the damage caused by an immense flood. A friend and I volunteered and my father asked if we could do a story for the magazine. I was impressed by the damage, and the spirit of the Dutch. I realized that the only way the world would learn about this was through National Geographic. It changed my life. I was hooked on the power of storytelling and discovered the power of journalism.

You joined the “family firm” as a picture editor for the magazine, became editor at 39, and published a package on pollution signaling that the rose-colored glasses the magazine was derided for were off. Perhaps most controversial was the June 1977 story on South Africa that took a hard look at apartheid and its legacy of poverty. Its government disparaged it as biased.

When we sent an advance copy of the issue to South Africa’s ambassador Pik Botha, he summoned me to his office. He was furious. When I challenged him and pointed to a copy of Time that had a story that pulverized his country, Botha picked up the copy of our magazine, slammed it on his desk, and roared: “You don’t understand. People believe what you write!”

Botha “had inadvertently put his finger on the pulse that made us tick,” you write in your book. Certainly, trust is more relevant than ever in an era of “fake news.”

Yes, that trust is invested in the Geographic staff, and especially in the magazine’s researchers [fact-checkers].

The South Africa article also ignited a firestorm among some board members who disapproved. The threat of an editorial oversight committee hovered over the magazine.

I was determined not to lose editorial control. I drowned them [the board] in paper. I had a cart wheeled in with stacks of documentation showing the endless fact-checking we did to ensure accuracy, proving every word had been double and triple checked before publication. Ultimately, editorial integrity won.

Let’s talk about women who had an important role in the Society, starting with your grandmother, Elsie Bell Grosvenor.

She would stay up late at night with Gramp while he worked to transform the magazine. She designed the National Geographic flag. She was a suffragette and made him march down Pennsylvania Avenue with her in the Women’s Suffrage Parade in 1913. There was also Eliza Scidmore. She urged my grandfather to run color photographs in the magazine and was responsible for the Japanese cherry trees planted around the Tidal Basin. There were women photographers in the early days, too, like Scidmore and Harriet Chalmers Adams—not to mention contemporary explorers and scientists like Jane Goodall, Sylvia Earle, Eugenie Clark, Dian Fossey, and Birute Galdikas.

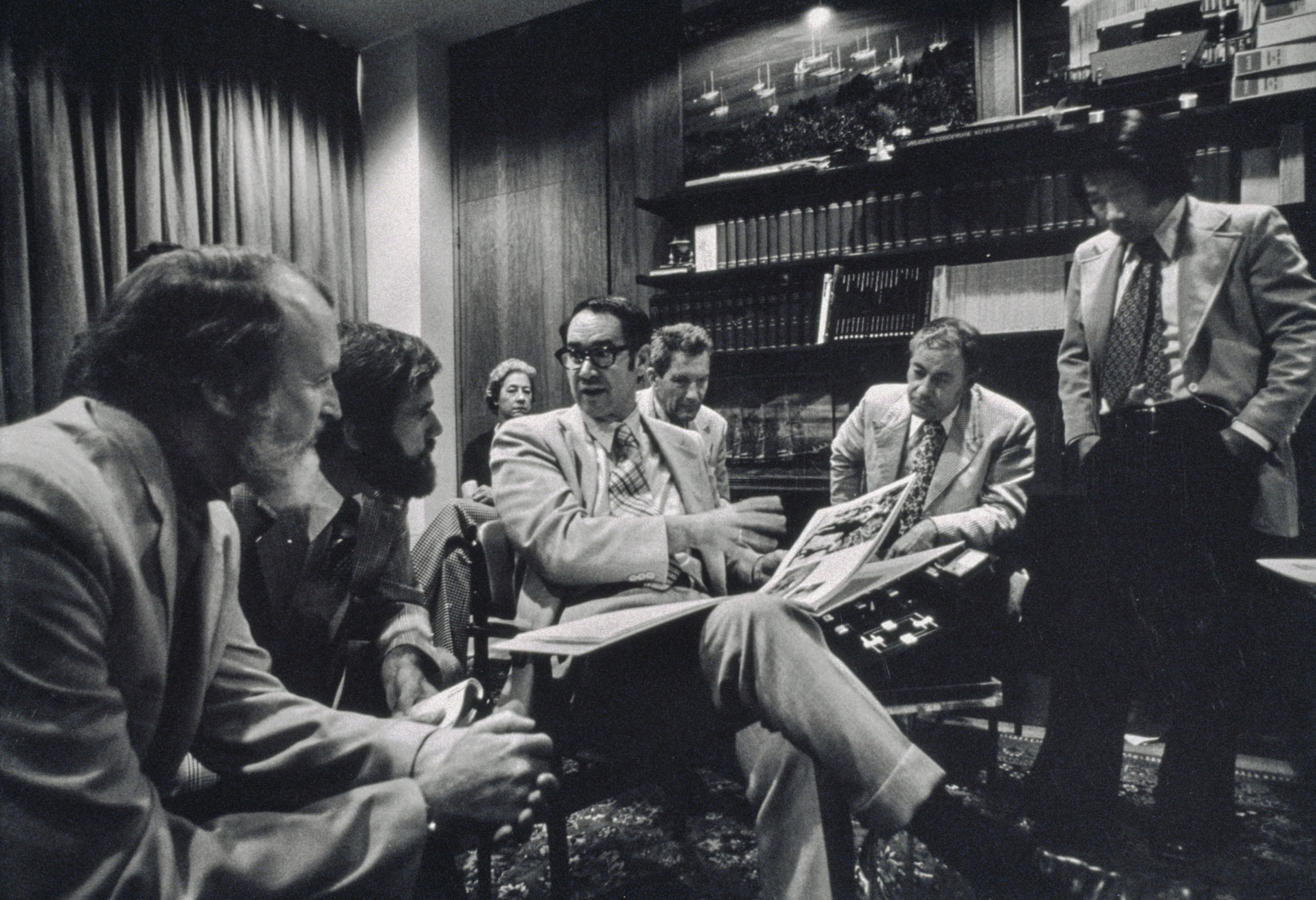

The magazine staff was notable for some larger-than-life characters.

They kept the magazine vibrant. When Luis Marden—who became head of the Foreign Editorial Staff— came for his job interview in the 1930s, he flew a fabric covered plane down from Boston. Luis found the bones of the H.M.S. Bounty, pioneered underwater color photography, discovered a new species of orchid that was named after him, and retraced Columbus’s voyage using the original fleet’s log. As a teenager he’d learned Egyptian hieroglyphics. Then there was my best friend Tom Abercrombie, a pioneer of modern photography in the magazine, credited with being the first journalist to set foot on the South Pole. He also retraced the 1,600-mile frankincense trail across the Arabian Peninsula and was fluent in Arabic. And Franc Shor, a senior editor who claimed to know every royal family in the world and spoke Turkish, Persian, and Mandarin. He was corporeally larger than life too, prone to excess. He kept his own wine cellar at the Ritz in Paris.

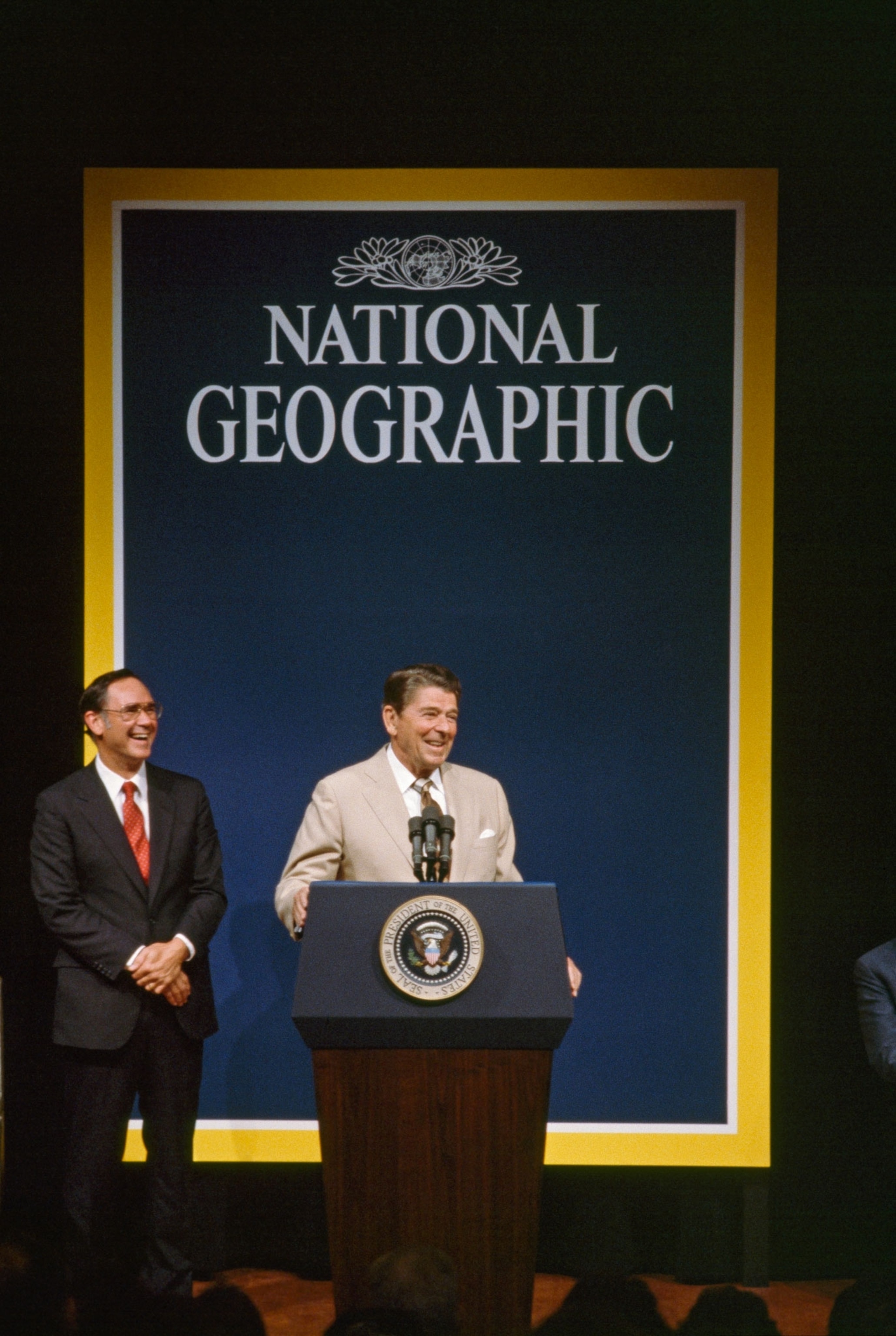

“It was proverbial that no one threw the magazine away,” you write. Even in this digital age, many homes have sagging shelves of the yellow magazine. President Ronald Regan alluded to that when he dedicated a new building on the National Geographic campus in 1984.

President Reagan came to our auditorium, looked around the cavernous room, gestured to the building and said with impeccable timing. “I guess you have trouble storing your old National Geographics, too.” It brought down the house.

You’ve said: “If you don’t know where you are, you are nowhere,” so let’s consider geography. After all, the organization is the National Geographic Society and the magazine National Geographic. Why is geography important?

Geography affects almost everything. Take Ukraine. To understand why it’s important you need to know it’s a buffer between Russia and Europe. It’s one of the world’s largest exporters of wheat and supplies 40 percent of the world’s sunflower oil. I’m looking outside the window of my cabin at the currents and tide. Why is it that a bottle released off the coast of Florida ends up in Ireland? That’s the Gulf Stream at work. What about the dramatic shift of flora and fauna to the north? That’s global warming. Knowing geography is to understand the world and its problems—not just political ones, but climate change, desertification, acidifying oceans, patterns of migration. We must learn geography if we are to become better stewards of the world we live in, and if we are to ensure our quality of life—perhaps even our survival.

Despite the challenges—which are many—you end on an optimistic note.

I believe we can be resilient and adaptive. We can and do preserve vast tracts of forest and sustainably harvest only necessary timber. We can harness cleaner energy. We can set aside vast tracts of coral reef and other marine biodiversity hotspots in the ocean.

What advice do you have for your successors?

Do what we do best. Not what others do.