How Sylvia Earle fell in love with the ocean—and why she never stopped exploring

At 90, Sylvia Earle looks back on decades of discovery, and forward to a future worth protecting.

Pioneering marine biologist Sylvia Earle grew up along the sea—the right place for the right person to begin a prolific career built on exploring and protecting the ocean.

To date, Earle has led more than 100 ocean expeditions, logged over 7,000 hours underwater, authored more than 190 scientific papers, and published 13 books. She became the first female chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 1990 and is currently a National Geographic Explorer at Large.

But long before her accolades, she was a 12-year-old girl living just north of Clearwater, Florida, where tangled mangrove roots met the tide and seawalls had yet to scar the shoreline. In the late 1940s, the sea water was true to its name—glass-clear, alive with fish and seagrass. That coast is now hardened, paved, and hemmed in by concrete; a high-rise condo stands where her childhood home once looked out over the bay. The lush underwater prairies she once catalogued in exquisite detail thinned to patchwork, the fish are far fewer, and wide stretches of seafloor lay bare.

This is where she began to witness the profound changes to the ocean that Earle, newly 90 on August 30, has spent a lifetime trying to prevent.

“When I started to explore the ocean in the 1950s, I became witness to its radical changes,” says Earle. “In my time, I’ve seen the loss of half of the ocean's wildlife, both in terms of numbers as well as diversity.”

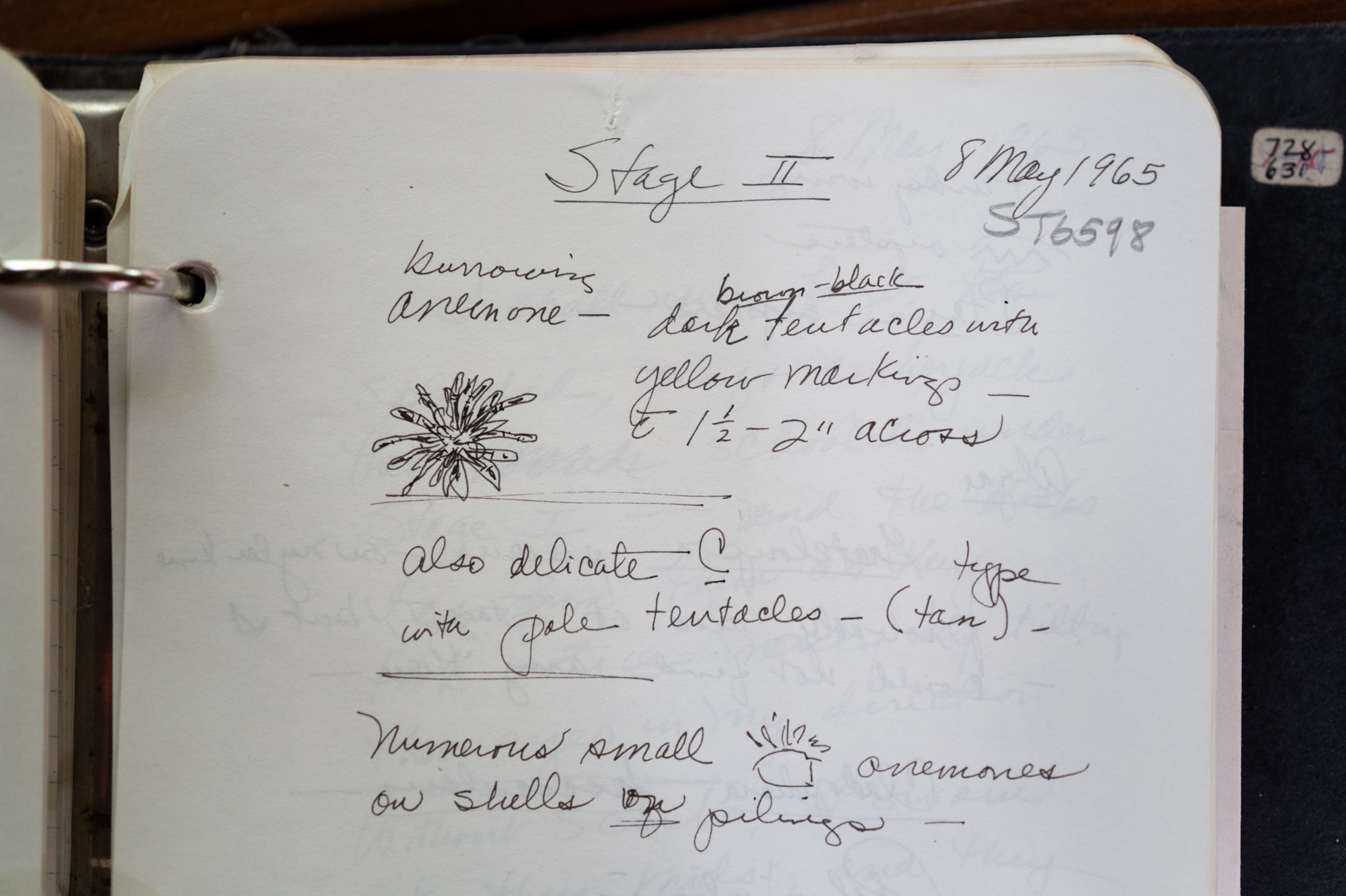

From her first steps along the shoreline to her record-breaking descents into the deep, Earle has lived in a state of devotion to the sea. Drawn first to botany, she pressed seaweed with a precision and tenderness that spoke of reverence as much as rigor—a way of seeing that has always defined her science. Love, curiosity, and an irrepressible zest for discovery still carries her into the water today.

Earle remains a leading voice on ocean science and policy. Two of her ongoing National Geographic projects are working to protect waters along from the Florida Gulf Coast and in Mozambique. And her “Hope Spots,” designated by her nonprofit ocean conservation organization Mission Blue, are still identifying parts of the ocean where marine parks can have the biggest conservation impact.

“We have learned more in the last 50 years than we had in all preceding human history,” she says. “And yet, that same half-century has also brought the greatest losses the seas have ever known.”

Finding companions beneath the ocean’s surface

Eighty-seven summers ago, before her tween-age move to Florida and professional catapult, a three year old Sylvia Earle bounded through the dunes toward the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. Tiny footprints dotted the wet sand along the New Jersey shoreline as she zestfully entered the sea. Without warning a sudden surge of frothy water crashed atop her head, knocking her down.

Where others might have pulled their small child away from the tumbling whitewater, her mother instead recognized her daughter’s lit-up face. She scooped Sylvia into her arms, cradling her against the salty spray, and witnessed, for the first time, the sparkly-eyed countenance that Earle is known to have to this day when emerging from the ocean.

“She saw the big smile on my face and let me run back in,” says Earle, “And I’ve been running back in ever since.”

Her innate curiosity drew Sylvia to the ancient, helmet-shaped forms of horseshoe crabs she’d find washed up on the shore. While others on the beach recoiled with cries of “Don’t touch that!” and “It could sting you!” (which it can’t), a young Sylvia leaned closer, already sensing the need to shift how people viewed ocean creatures: not as strange and distant beings, but as marvels.

That early wonder and empathy for all living things would come to define an epic lifetime of exploration and stewardship, as she continued to lean in closer. Even then, the small imprints that Sylvia left in the sand that day hinted at the enduring mark she would one day make upon the ocean, and on all those who followed her work.

By the 1950s, Sylvia’s fascination with the seas had begun to take form. At sixteen, she made her first scuba dive—a moment that cemented her bond with the underwater world. In 1979, Earle made the dive that earned her the moniker ‘Her Deepness,’ and revealed to the world her contagious presence and boundless avidity for exploring the unknown reaches of our planet.

Riding the nose of a submarine in a record-breaking untethered dive to a depth of 1,250 feet off the coast of Oahu, she was the first woman to explore the ocean beyond 1,000 feet while wearing a JIM suit—a pressurized diving system that eliminates the need for decompression stops.

Beyond the reaches of sunlight, she encountered a luminous world in the deep ocean.

Whisker-like corals spiraled upward. Rings of bioluminescent blue algae pulsed through the water column as she reached out her gloved hand.

“Most of life on Earth lives in the dark, in cold, high-pressure environments that would be uninhabitable for us,” she reverently conveys. “We think of the sunlit upper portion as the ocean, where scuba divers go, and we think of the creatures there as representative of the sea. But 90 percent of the ocean is in permanent darkness, and many of the creatures there create their own light.”

Her work in the deep sea only further illuminated something she had always known: that each creature is a unique individual.

“Down there, it really comes into focus,” she says. “That fish is different from that one, and that one, and that one. I know the eel who lives in that place. Exploration and peeling back layers of the unknown has led me to the conviction that we have to protect as much of the natural fabric of life, land and sea, as possible.”

Finding hope amid a climate crisis

From her Florida hometown to habitats around the world, Earle remains committed to fighting for ocean conservation, and she’s doing so while mentoring the next generation of scientists and storytellers.

And while the loss of ocean life along the shores where she grew up once opened her eyes to how dramatically the coast can change, nearby she’s found the reassurance that her efforts are not in vain.

When visiting Crystal River, about two hours north of Tampa, in 2022—her first trip in half a century—she found something that felt almost like a homecoming. Unlike the hardened shorelines of Clearwater, this stretch of coast remains largely wild, its springs still feeding clear water into the Gulf.

Slipping beneath the surface, she felt she was among old friends again: seagrass swaying in the currents, algae painting the rocks in familiar greens, the underwater world still alive. This small stretch of coastal Florida is for her a wellspring of inspiration, even when the future feels dire.

“What a gift it is to be able to do things that no other creatures can,” she says, her voice carrying the awe of someone who has spent a lifetime underwater. “A dolphin can dive deep in the ocean, but we can go even deeper—and we can fly. We’re so lucky to be alive right now, as the greatest era of exploration is just beginning. This is the best chance we’ll ever have, despite the awesome, formidable challenges. And with that comes a special responsibility.”

It is a responsibility sharpened by a litany of loss. She notes the global loss of sharks and rays (down by 71 percent since 1970), the decline of coral reefs and subsequent loss of commercially caught fish (down 60 percent in the same timeframe); and ocean life decimated by industrial fishing (a practice that can slash the quantity of fish by 80 percent in 15 years, according to one model).

"You can see deforestation on land and recognize it as a major problem, but the ocean’s surface often appears unchanged,” says Earle. “This makes it difficult for people to realize that today’s ocean is only about half as healthy as it was when I first began exploring it and witnessing these dramatic changes firsthand."

At the same time, climate change is altering the oceans at an unprecedented pace.

Global sea surface temperatures have risen by roughly 1°C over the past century, while ocean acidification has increased by more than 30 percent , threatening entire marine ecosystems.

Yet even as she has witnessed this cascade of loss, Earle maintains a grounded hope—born from a lifetime of observation—that understanding our oceans is the best way to chart a better course.

“We must take care of the ocean and our natural living systems, as if our life depends on it,” she urges. “Because it does.”