Scientists found a way to reverse kidney damage—is a cure next?

Experts say we’re in a golden age for treating chronic kidney disease, with new drugs like Ozempic yielding major results. Will dialysis and organ transplants become a thing of the past?

Nicolas Palacios got the bad news on his daughter’s first birthday in July 2020. Palacios, who was 28 years old at the time, had lost his job a couple weeks earlier and was dealing with severe fatigue, which his doctor had called to tell him was in fact a symptom of Stage 4 kidney disease. Palacios was on the cusp of kidney failure. “It was the worst day of my life,” Palacios says.

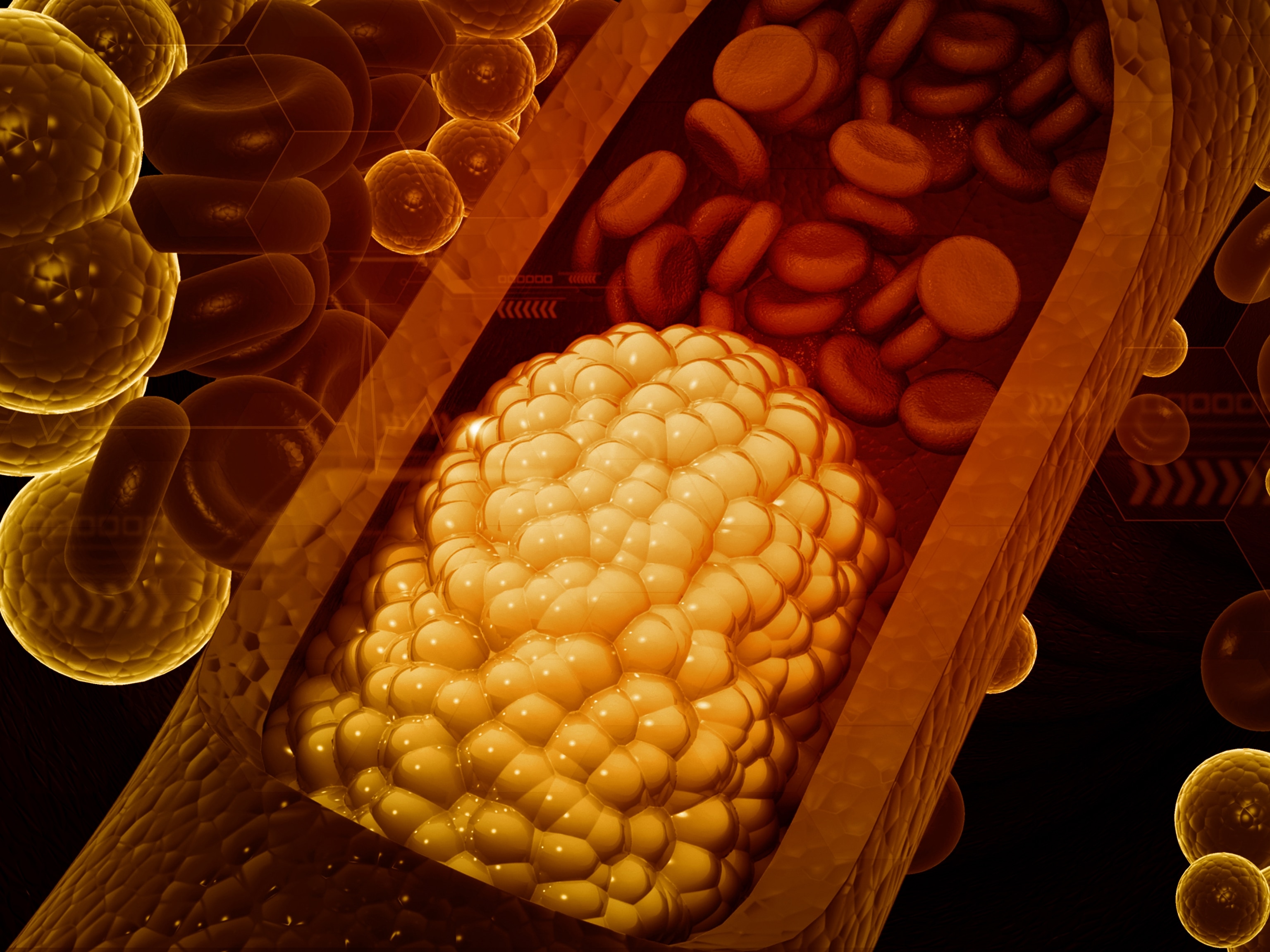

Being on the verge of kidney failure means facing a future with two options: going on dialysis for the rest of your life or getting a transplant, for which the waiting lists can take years. Meanwhile, you remain at an extremely high risk of dying from heart attack or stroke.

Palacios eventually was put on medications that stopped the rapid decline of his kidney disease, clawing him back from the verge of kidney failure. But he needed a miracle if he was going to avoid dialysis or a transplant.

That miracle came in the form of a clinical trial looking at the effects of tirzepatide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist that’s sold under the brand name Mounjaro, on chronic kidney disease.

During the trial, Palacios experienced a total transformation in his health and quality of life. His kidney function started to improve dramatically, to the point that he’s now classified as having Stage 3 kidney disease—meaning that if his condition is managed well, he can live a long and healthy life, without ever needing dialysis or a transplant.

(Chronic kidney disease is on the rise—and most people don't know they have it.)

“To say that it’s been a life-changer for me is an understatement,” Palacios says. “It gave me my life back.” He’s gone from wondering whether he will live long enough to see his daughter grow up, to making plans for a future that includes him in it.

Palacios’ experience is not an anomaly. In the past decade, there has been an influx of new treatments for various forms of chronic kidney disease, or CKD, that show a remarkable ability to preserve kidney function, and in some cases, even reverse the damage. This includes two classes of drugs that were originally developed for Type 2 diabetes, as well as an influx of other drugs that can treat less common forms of CKD. “In my 40 years being a nephrologist, I never saw patients [improve like Palacios],” says Katherine Tuttle, a researcher at the University of Washington. “And he’s not the only one.”

At the American Society of Nephrology’s annual meeting in November, Tuttle presented promising preliminary data showing that patients treated with semaglutide—another GLP-1 receptor agonist, sold as Ozempic—showed a stabilization in damage to the kidneys, and in some cases, even a reversal like Palacios experienced. This included improvements in inflammation and scarring within the kidney, as well as improvements in overall function.

These findings—and a slew of other advances—have ushered in a golden era of scientific research for chronic kidney disease, which affects an estimated 700 million people worldwide.

“We can start, for the first time, to really think about a cure for kidney disease,” says Vlado Perkovic, a researcher at the University of New South Wales, in Sydney, Australia. “For the first time, there’s a potentially visible, realistic pathway to go from remission to cure.”

Options have historically been limited

Until recently, the options for treating chronic kidney disease have been limited, with dialysis or a kidney transplant being the mainstay of treatment. For Jullie Hoggan, who was diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease in 1998, her doctor told her to “come back in 20 years when [your kidneys] fail.”

Although dialysis will keep a patient alive, it’s expensive, time-consuming—many patients must undergo hours-long treatments several times a week. It’s also rough on the body, with patients experiencing side effects such as fatigue, cramping, nausea, sleep disturbances, electrolyte imbalance and the risk of infection. For patients who do go on dialysis, only 35 percent of them will be still alive after 5 years.

(Inside the audacious plan to solve the organ donor crisis.)

“People with kidney failure live about a quarter as long as people with normal kidney function, and they have a dramatically reduced quality of life,” Perkovic says. “They’re tired, they have shortness of breath, they can't think straight.”

The other option has been a kidney transplant, for which there are long waiting lists, as well as a need to take immunosuppressant medications, in order to keep the body from rejecting the transplanted organ. It’s also not a lifelong solution, as a transplanted kidney will last an average of 12 to 20 years.

An influx of new chronic kidney disease therapies

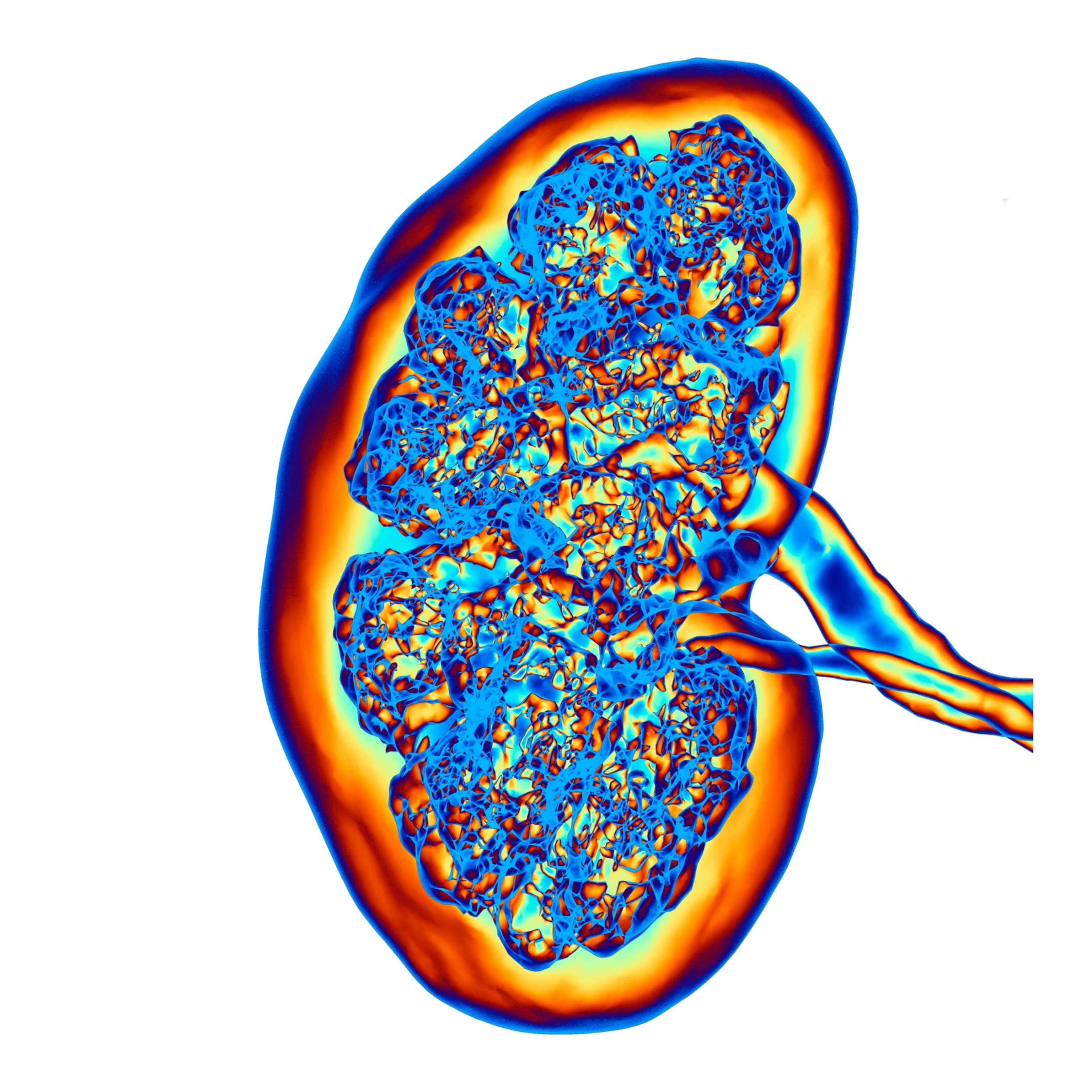

In recent years, there has been an influx of new treatments for various forms of CKD. This started in 2019, with trials showing that a class of diabetes drugs known as SGLT2 inhibitors were beneficial for patients who had diabetic CKD, the most common form of chronic kidney disease affecting 59 percent of people with kidney failure.

SGLT2 inhibitors stop the kidneys from reabsorbing glucose, which can lower blood sugar. It’s still not entirely clear why they are so good for the kidneys, but it’s probably because the proximal tube epithelial cells in the kidney use a lot of energy to reabsorb glucose, says Rafael Kramann, a researcher at RWTH Aachen University, in Aachen, Germany. “If you stop them from using this energy for reabsorption of glucose, they probably have more energy to respond to injury, and they can adapt better.”

What is very clear is that SGLT2 inhibitors have a powerful effect on protecting the kidneys, with many of the trials being stopped early for efficacy, due to how well they prevented kidney failure and deaths from heart attacks and strokes. SGLT2 inhibitors were later shown to be similarly beneficial in patients with non-diabetic CKD.

(It’s possible to reverse diabetes—and even faster than you think.)

Researchers have since seen the same thing with the newest class of diabetes drugs, GLP-1 receptor agonists like Ozempic.

In 2024, a Phase 3 clinical trial found that semaglutide was highly effective at preventing end-stage kidney failure and deaths from cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetic CKD. This trial was ended early for efficacy, as the rate of kidney failure and death was so much lower in the group that received semaglutide it was no longer considered ethical to continue giving patients a placebo.

Tuttle’s ongoing REMODEL trial, a placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, randomized trial, is following up on those results and unlocking exactly what it is about semaglutide that improves kidney function. These results are “explained by profound changes in function, as well as structure, at a molecular level,” says Tuttle. “It’s reprogramming the way these organs work.”

Ozempic has since been approved for diabetic CKD but trials examining whether it and other GLP-1 receptor agonists will also be beneficial for non-diabetic CKD are ongoing. Still these are likely to show a benefit as well, based on preliminary evidence. For example, Palacios has seen a major benefit from tirzepatide, in spite of the fact that he has non-diabetic CKD.

In addition to SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, there are two additional classes of drugs that are approved for diabetic CKD. These drugs have different mechanisms of action, which means that combining them can confer additional benefits. In fact, studies suggest that combining all four drugs that are approved for diabetic CKD can reduce the risk for kidney failure by up to 58 percent.

“The question is, how do we use them together for an individual patient?” says Prabir Roy-Chaudhury, a nephrologist at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. “That’s the challenge.”

Future innovations—and potentially a cure?

There still aren’t quite as many treatment options available for non-diabetic CKD, but that is rapidly changing—and there’s reason to believe the next decade is going to be yet another one of innovation in kidney care.

This includes more treatments for IgA nephropathy, an autoimmune disorder that often leads to kidney failure. In recent years, there have been three new treatments approved, some of which can effectively put patients into remission. These new treatments selectively target the cell type that is causing the damage, which has the effect of stopping the disease progression in its tracks.

“We’re actually treating the cause of the disease, rather than just the consequences,” Perkovic says.

Part of what has driven these innovations is a new strategy that has made clinical trials for kidney disease more cost-effective. “Kidney trials are super expensive,” Kramann says. “You need a lot of patients, and a lot of run-time to actually detect differences.”

For IgA nephropathy, researchers devised a new strategy for measuring the decline in kidney function, that was faster and more precise. This has allowed clinical trials to be conducted more efficiently, within a period of several years, compared to the past, when trials went on for many years, sometimes even decades, and could cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

As a result, there are hundreds of clinical trials targeting different types of kidney disease in the pipeline, including 70 active clinical trials focused on IgA nephropathy alone. It’s placed the world of kidney care at a point where researchers and clinicians can realistically expect to put their patients into long-term remission, and perhaps one day curing them.

For Palacios, being on tirzepatide has changed the course of his illness, giving him his life back, and allowing him to care for his family. He’s still on tirzepatide, although he has to pay for it out-of-pocket, as it’s not currently approved for treating chronic kidney disease.

Even with this hurdle, he considers tirzepatide to be a life-saving and life-changing medicine. “It’s no longer about delaying how much worse you are going to get, it’s now about how much better can you get,” Palacios says.