Warship's Last Survivors Recall Sinking in Shark-Infested Waters

Seventy years later, veterans of an epic naval disaster gather to share stories of suffering, reconciliation, and healing.

It was the worst naval disaster at sea in U.S. history.

Seventy years ago this week, on July 30, 1945, the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Indianapolis was sunk by two torpedoes fired by a Japanese submarine in the south Pacific. So began a five-day ordeal of thirst, hypothermia, salt-water poisoning, hallucination, drowning, and dismemberment in shark-infested waters.

Out of a crew of 1,196, only 317 men survived.

For years the story seemed destined to be forgotten. Until the movie Jaws hit theaters in 1975, and Captain Quint’s now-infamous monologue about the relentless shark attacks thrust the Indianapolis incident into public consciousness, it seemed almost no one knew about it. (Read about the string of shark attacks that inspired Jaws.)

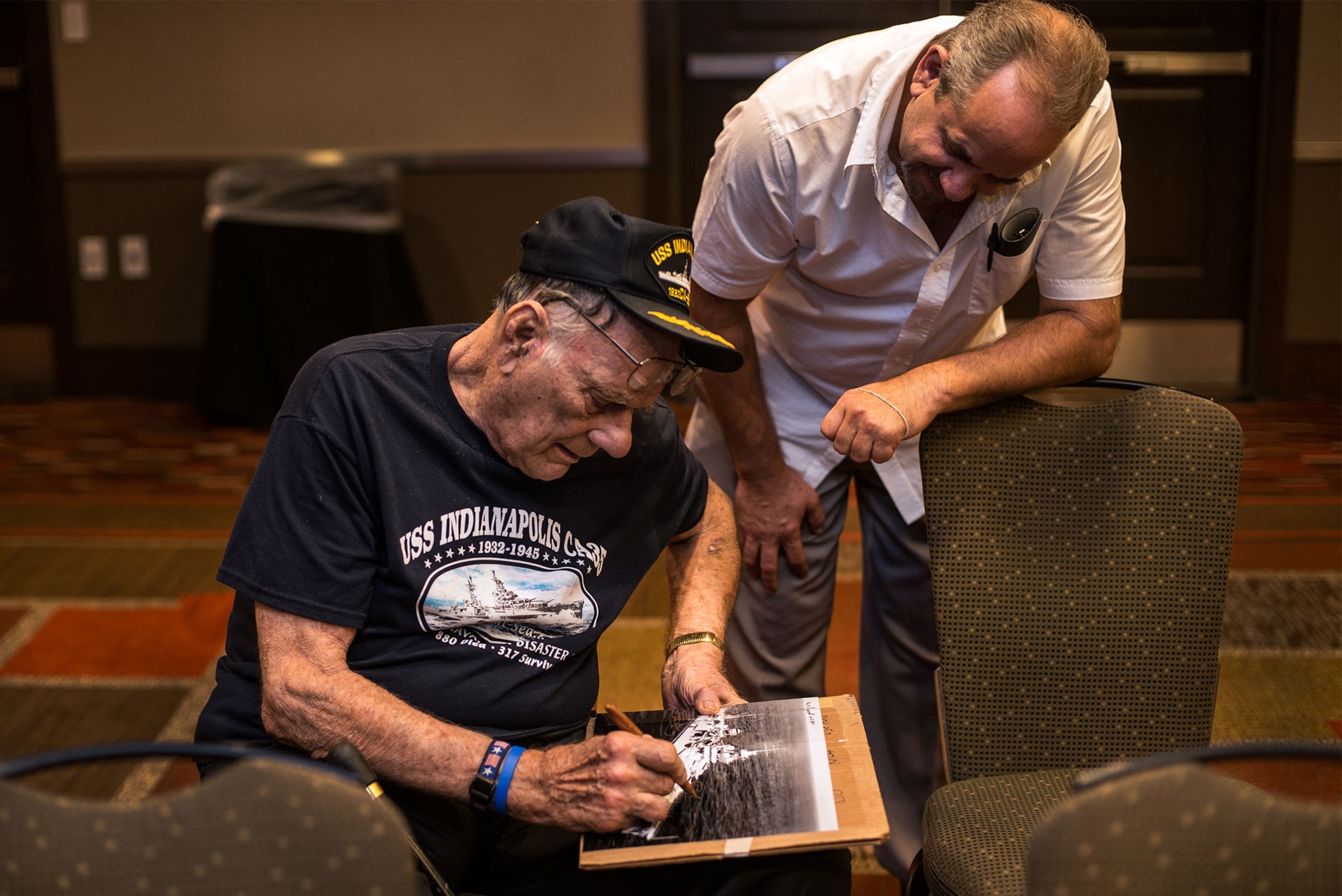

The survivors, of course, found the event impossible to forget. Since 1960, they’ve been meeting for reunions in Indianapolis to bond with their shipmates, tell their stories, and commemorate the worst week of their lives.

In Their Own Words

As last weekend approached, 14 of the 31 remaining survivors gathered here for the 70th anniversary of the incident. It was not lost on the hundreds of family members, friends, and dignitaries in attendance that there may not be a similar gathering on the 75th. The reunions have been held annually for the last few years (after being biannual for several years before that), but with most of the survivors in their nineties, a vote is now taken every year whether to continue.

For an event that on first glance seems overshadowed by death—past and future—the primary tone is celebratory.

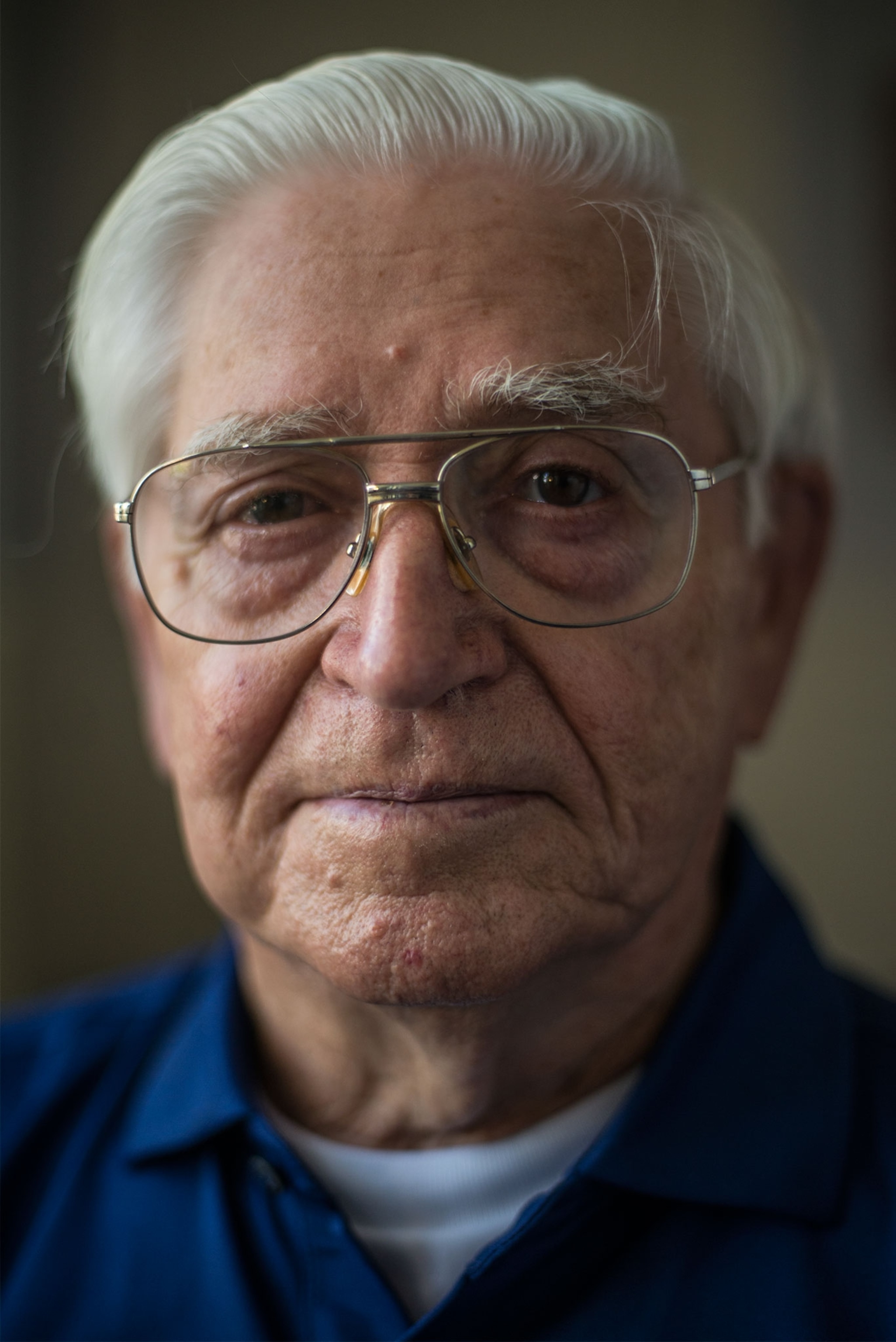

“Our numbers are dropping fast” says Harold Bray, a retired police officer from Benicia, California, who at 88 is the youngest survivor left. “We’ve lost three since the last reunion. It’s really tough to belong to a club like this.”

An Unexpected Celebration

But for an event that on first glance seems overshadowed by death—past and future—the primary tone is celebratory. Because the story of the U.S.S. Indianapolis is not just a story of sharks, or suffering, or even survival. It’s a story that Quint, who in Jaws had his tattoo of the U.S.S. Indianapolis removed because he wanted no reminders of the event, would not even recognize. (Read 'What You Should Know about Shark Attacks.")

It’s a story of victory. Four days before their ship was sunk, the crew of the Indianapolis landed at Tinian island and delivered the components for the atomic bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima less than two weeks later, bringing a fast end to World War II. By the time the survivors recovered from their ordeal—most were on the brink of death when they were accidently spotted and rescued by a passing pilot—the war was over.

It’s a story of reconciliation. Among the guests at this year’s reunion were the daughter and granddaughter of Mochitsura Hashimoto, the Japanese submarine commander who ordered the sinking of the Indianapolis.

“At first I wasn’t sure if I would feel like the enemy,” says Atsuko Iida, the granddaughter, who lives in Centralia, Illinois, and came to her first reunion in 2001. But she was warmly embraced, and the forgiveness goes both ways. Iida joined the applause when a speaker mentioned the Hiroshima bombing as the catalyst for the war’s end, even though her grandfather’s family lived in the suburbs of Hiroshima when the bomb was dropped.

'Biggest Thing For Me Healing Up'

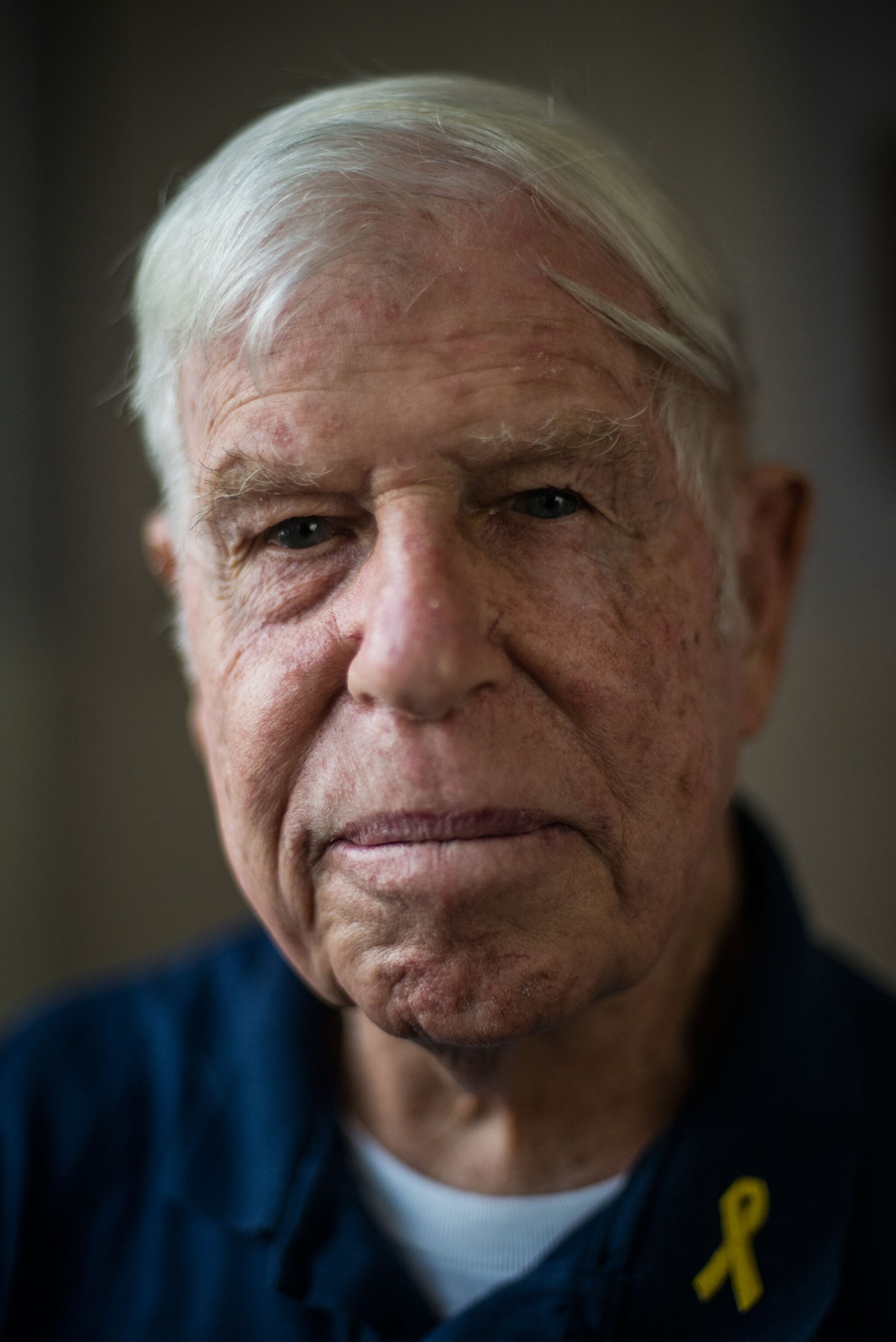

It’s a story of healing. “We all came home and tried to forget the war,” says Dick Thelan, a burly survivor from Lansing, Michigan, who drove trucks for 44 years. “In seven years, I didn’t say one word to my wife about the sinking. She didn’t know nothing.”

That was the rule, and if there were exceptions, they were rare—until the survivors began gathering for reunions. There they began talking about their experiences with each other, which made it easier to finally talk about them with their families.

“That relieved a lot of pressure off a lot of people, including myself,” Thelan says. “I think it’s very important for my family to know what happened. I’ve got five kids here, and grandkids—four generations will be here this weekend. This reunion has been the biggest thing for me healing up.”

It’s a story of appreciation. When 91-year-old survivor Cleatus Lebow arrived at the Indianapolis airport on Thursday from his home in Memphis, Texas, he was wheeled off the plane to a cheering crowd organized by the USO.

“I’ll bet you there were 3,000 people there, all clapping and waving flags,” he says, tearing up. “It was the best feeling I’ve ever had.” (Jeff Lupe, the USO coordinator, says the number was in the hundreds, not the thousands, but that’s just quibbling. As one survivor told him, “This is the reception we didn’t get when we returned from the war.”)

It’s a story of heroism from unexpected sources, and the eventual righting of long-standing wrongs.

It’s a story of heroism from unexpected sources, and the eventual righting of long-standing wrongs. One of the most honored guests at this year’s reunion was Hunter Scott, who as an adolescent became obsessed with clearing the name of the Indy’s captain, Charles B. McVay III, who was court-martialed for his decisions the night the ship was sunk.

To a man, the survivors of the Indianapolis had long considered their captain a scapegoat for the Navy’s failure to realize the ship was missing and send out search parties. Their five days waiting in vain and dying in droves? Not McVay’s fault, but the Navy’s. Thanks in no small part to Scott’s perseverance, McVay was exonerated by the U.S. Congress and President Clinton in 2000.

One Less Survivor

It’s a story of a broad and deep community. “I’ve been coming to these reunions since I was ten years old,” says Carol Burnside, the daughter of Chuck Gwinn, the pilot who spotted the surviving crew of the Indy bobbing in the ocean on the fourth day of their ordeal. (The survivors call him “the angel”).

“I’ve been in most of these men’s homes,” Burnside says. “I’ve grown up with their children. I’ve seen their kids get married. They embrace anybody who wants to know their story.” Which is why the reunions keep getting bigger, even as the survivors keep dwindling in number.

And it’s a story of faith—in life, and in the ability to carry on no matter what life brings.

Sunday morning, as a memorial service for the deceased drew the reunion to a close, the announcement came that Florian Stamm, a 91-year-old survivor from Wisconsin, had died the night before in his nursing home. His 24-year-old grandson Mitchell Stamm, who in college made a film about the Indianapolis survivors for a class project, placed a rose in a vase on the stage in his honor, as his parents watched from their seats.

There are now 31 living survivors of the U.S.S. Indianapolis. The reunion is on for next year.

Follow Glenn Hodges on Twitter.