How the ancient Romans became the world's greatest builders

The expansion of one of the Mediterranean’s strongest powers wasn’t only driven by conquest, but also infrastructure. By borrowing techniques from the Greeks and the Etruscans, Romans engineered massive bridges, aqueducts, and roads—some of which still stand proud.

The Roman world was bound to the capital by the invisible web of law and custom, and a tangible network of roads, aqueducts, sewers, and ports. This spectacle of infrastructure, whose ruins still provoke awe, proclaimed Rome’s preeminence across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Engineering was one of Rome’s most lasting legacies. Adopting technologies already invented by the Greeks, Etruscans, Egyptians, and Babylonians, the Romans refined them with their own utilitarian spirit.

Utility, or utilitas, was central to Roman thinking. Vitruvius, the first-century B.C. Roman engineer, architect, and theorist, reflected on his admiration for the mathematicians and engineers on whom Roman greatness was built: “men whose researches are an everlasting possession, not only for the improvement of character but also for general utility.”

Overcoming nature

The first-century A.D. historian Tacitus once wrote about two engineers who designed a canal more than a hundred miles long for Emperor Nero to link the Bay of Baiae near Naples to the Tiber River. The canal was never built, but Tacitus’s words express the reverence with which Romans regarded engineers: “The architects and engineers were Severus and Celer, who had the ingenuity and the courage to try the force of art even against the veto of nature.”

The secret to Rome’s infrastructure triumphs lay in putting centuries-old discoveries in mathematics, physics, and chemistry to practical use. The laws of hydraulics (the practical application of fluid mechanics) and hydrodynamics (the science of fluids in motion), for example, was largely defined by Archimedes in the third century B.C., and put into practice when the Romans began building cisterns, aqueducts, and ports. Advances in topography and mapmaking from Egypt, Greece, and Etruria were the basis for the Roman system of surveying, known as centuriation, the first step in building their roads and other infrastructure.

Rome was the first power to implement large-scale civil, mechanical, and military engineering across all its territory. Many of these constructions remained in use for centuries, or even millennia, and some Roman roads, aqueducts, bridges, and ports are still used to this day. Their amphitheaters, circuses, and basilicas also still rise above modern streets across Europe. The longevity of these monuments comes from the Romans’ unwavering commitment to quality: no shortcuts, always using the best materials, and precise craftsmanship. Every detail mattered.

Greek ideas, Roman practice

On the road

Many of the most recognizable and durable Roman structures are related to transportation. The empire’s territorial expansion relied on a robust network of roads to ensure its political and cultural cohesion. At its peak, during the early second century A.D., Rome came to rule around one-fifth to one-quarter of the world’s population, across more than two million square miles connected by 200,000 miles of roads, of which over 53,000 were paved.

When Roman engineers designed these roads, their priority was to ensure smooth travel for wheeled transport, and routes were carefully chosen. They had to resort to different solutions based on the relief of the terrain. When crossing mountain ranges, they always opted for the most accessible side, the lowest hill, and the sunniest slope. The least steep gradient was chosen and water was avoided at all costs. Despite these methods, they still faced many challenges.

(This Roman emperor had a decadent grotto by the sea. Here's what was inside.)

Flat or undulating areas were the easiest to cross. Irregularities in the terrain were usually smoothed with embankments. Adding materials from quarries created various strata under the road surface, which is why roads were also called strata (a term that gave rise to strada in Italian and “street” in English). In other stretches, the land had to be excavated to build the road. On the Appian Way at Terracina, workers famously cut through 120 feet of rock—a feat still marked by an ancient inscription.

Water posed the biggest challenge, threatening the stability and durability of the infrastructure. With a lake or swamp, the problem could be easily solved by draining large areas with ditches or drainage channels. The small structures or pipes would be unseen by travelers.

Rivers required bridges, often the most difficult and resource-intensive structures to build. Bridges became one of the great symbols of Roman civilization, but they are also among those that have proven least able to withstand the passage of time.

The percentage of stone bridges from the Roman period that have survived to this day is minimal. Most succumbed to natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, fell into disrepair with the collapse of Roman authority, or were dismantled over centuries as convenient quarries for newer buildings. However, a small number did endure thanks to a combination of their location, construction quality, and continued use. Bridges like the second-century A.D. Alcántara Bridge in southwestern Spain and the first-century B.C. Pont-Saint-Martin in northern Italy were built in geologically stable areas, away from the most destructive river currents. Their massive stone arches were expertly engineered to distribute weight and withstand hydraulic pressure. Crucially, many of these bridges remained vital transport links for medieval and early modern communities, which ensured their maintenance. Some, like the first-century A.D. Pont du Gard in southern France, were even repurposed and protected by later rulers who recognized their utility or symbolic value. Their survival is as much a result of pragmatic continuity as it is of Roman craftsmanship.

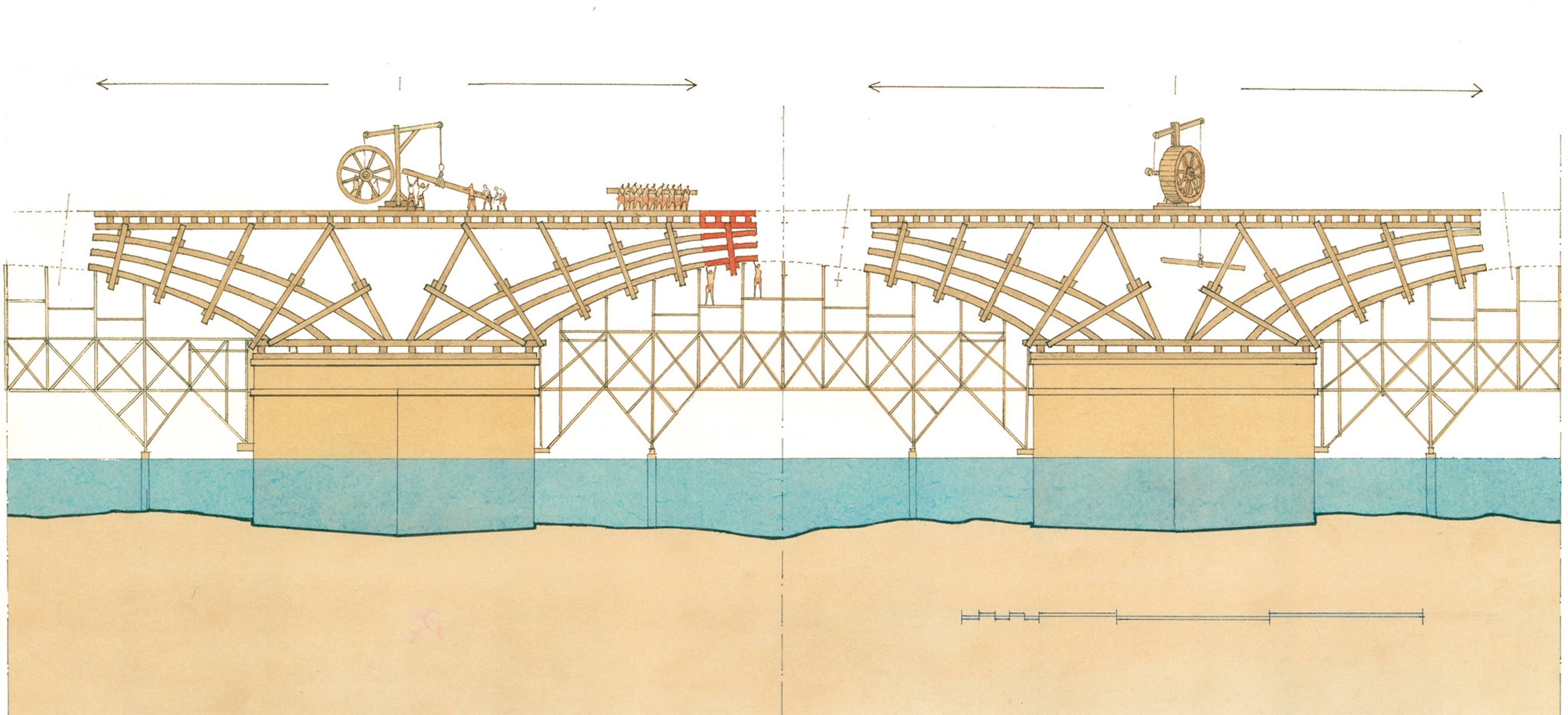

Double trouble

Building a bridge posed a dual challenge. First, its foundations had to be secure: Vertical piles had to be driven deep into the riverbed to provide a stable base. Second, the bridge needed to span the entire distance between the two banks with enough strength to support the raised roadway and bear the weight of carts, pack animals, and legions of marching soldiers. Time and again, Roman engineers demonstrated remarkable skill in solving both problems, combining precise structural knowledge with innovative construction techniques.

Rome: A lab for bridge building

Pons Fabricius, with its two wide arches each spanning about 81 feet, remains the oldest surviving bridge in Rome in its original form. A central opening in its supporting pier serves as an overflow channel, reducing pressure from the river’s current. These structures reflect the Romans’ ability to adapt and innovate in response to challenges posed by their natural environment.

The earliest Roman bridges were made of wood and followed the traditional Greek design, in which horizontal beams were laid across vertical supports to form a post-and-lintel (or architrave) structure. This simple framework rested on rows of wooden pillars set into the riverbed. In the city of Rome, the earliest known bridge was the Pons Sublicius, which crossed the Tiber River near the Forum Boarium. According to tradition, it was built in the seventh century B.C. It got its name, meaning “bridge of wooden piles,” because of the sublicae, the timber supports lodged into the ground. Over time, the Romans realized that this post-and-lintel structure was too weak to support carts, marching legions, and other heavy traffic. Wooden bridges, valued for their ease of construction and removal, continued to be used in military contexts to enable the crossing of small numbers of troops.

(Who was Pliny the Younger? Why his account was the only to survive Pompeii)

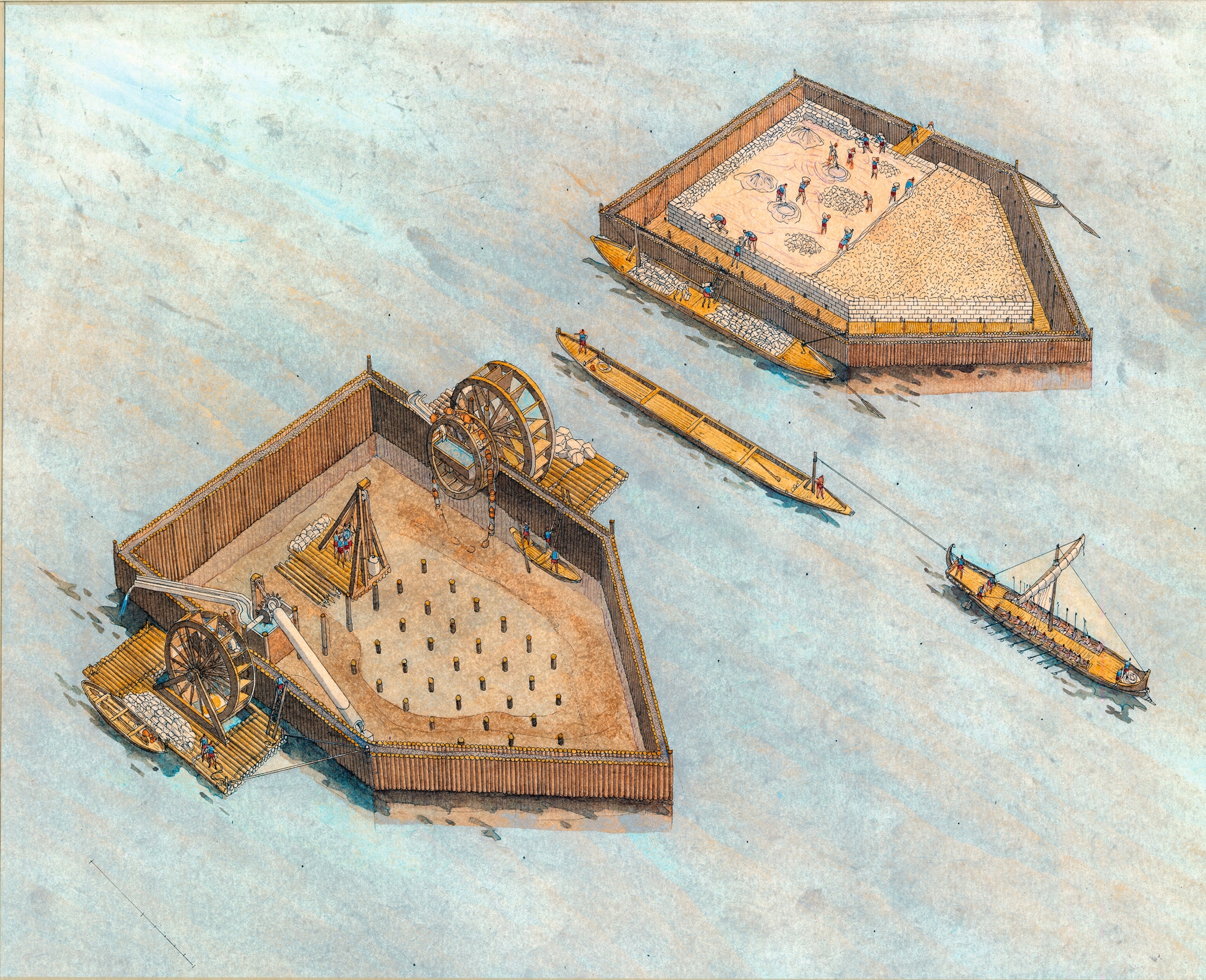

Bridging the Rhine

In 55 B.C., Julius Caesar’s legions built a bridge over the Rhine, an audacious feat of military engineering that was unmatched in the ancient world. Caesar wrote in The Gallic Wars that he “had decided to cross the Rhine; but he deemed it scarcely safe, and ruled it unworthy of his own and the Romans’ dignity, to cross in boats. And so, although he was confronted with the greatest difficulty in making a bridge, by reason of the breadth, the rapidity, and the depth of the river, he still thought that he must make that effort, or else not take his army across.” In just 10 days, the Romans spanned the wide, fast-moving river, marched across, and then dismantled the entire bridge to deny its use to the enemy.

For more flexible crossings, Roman engineers often relied on pontoon bridges. These floating structures used boats placed side by side with a deck laid across the top, supported by vertical posts. They were quick to assemble and ideal for wide, flood-prone rivers like the Rhône in modern-day France, where a permanent stone bridge was too costly, or even impossible, to build.

Arch revolutionaries

The quintessential Roman bridges were built of stone. Although these bridges weren’t a Roman invention, the Romans revolutionized the form with a key innovation: the round arch. This simple yet solid design became the cornerstone of Roman engineering.

In an arch, each wedge-shaped stone, or voussoir, transfers its weight to the next, directing the load outward and downward toward the foundations. The central key- stone locks the entire structure in place. With fewer support piers needed, arches allowed the Romans to span wide rivers with graceful, durable bridges.

The Pont Saint-Martin in Italy’s Aosta Valley was built near the Roman city of Augusta Praetoria. This single-arch bridge stretches just over a hundred feet across the riverbed. Its construction was so daring that medieval locals believed it was built by the devil.

Other bridges reached even grander scales. Spain’s Alcántara Bridge is one of the tallest Roman bridges in the world at 180 feet high. But it’s outmatched in length by the bridge at Augusta Emerita, now Mérida, also in Spain, which stretches 2,592 feet across the Guadiana River with 60 arches still intact.

The Alcántara Bridge

Some of the most ambitious bridges have vanished. Trajan’s bridge over the Danube, completed between A.D. 103 and 105, was a hybrid marvel. Massive stone piers supported timber arches (later replaced by stone), extending a total of half a mile across the river. A carving on Trajan’s Column commemorates its bold design. The Roman historian Cassius Dio was awestruck: “Trajan constructed ... a stone bridge for which I cannot sufficiently admire him. Brilliant indeed, as are his other achievements, yet this surpasses them.”

Even that bridge was later exceeded in scale. In A.D. 328, Emperor Constantine commissioned a bridge across the Danube that stretched for one and a half miles. It lasted only 40 years, but was the longest bridge in antiquity. Still today, with massive advances in structural engineering, it remains among the longest bridges ever built.

Ordered by the emperor

In the imperial era (from 27 B.C.), the emperor himself directed major infrastructure projects, though execution was often delegated to governors, proconsuls, or imperial procurators. These officials’ names were sometimes inscribed on the structures they commissioned. Funding typically came from the public treasury, but private contributions were occasionally accepted—particularly for enhancements like widening a road or adding decorative features. Wealthy local patrons gained prestige in return for their support. While Roman legions sometimes helped carry out construction, especially during campaigns, most of the work was completed by teams of laborers or enslaved people. This strategic approach ensured that Roman infrastructure served both practical and symbolic purposes across the empire.

Foundations of a modern world

The Romans made major structural advances in another key component of their transport network: the ports that kept sea trade moving and Rome provisioned.

Roman engineers mixed volcanic ash, lime, and seawater into their concrete to create a material that could set hard under water. This invention was a game changer for structural engineering, enabling the construction and repair of even more sophisticated aqueducts and seaports.

Thanks to the advances in Roman concrete, harbors no longer needed to cling to natural protective features, and could expand under the protection of seawalls and piers. Completed by the Emperor Trajan in A.D. 110, the massive concrete foundations of the port of Centum Cellae, just under 40 miles northwest of Rome, underlie the modern port of Civitavecchia. The cruise liners and trans-Mediterranean ferries that arrive in the port today moor directly above the massive Trajan-era structures that have endured time and tide for nearly two millennia.

Along with ports such as Civitavecchia, the foundations of many Roman bridges, roads, and aqueducts continue to support modern infrastructure. Together with the physical foundations is the idea of modern states, in which political control depends on technical advances facilitating the movement of goods and troops. Engineering solutions that took roads through previously impassable terrain strengthened Rome’s grip over increasingly far-flung territories.

By the late Republic, speed on the road was synonymous with power. In the Lives of the Caesars, historian Suetonius describes the remarkable rapidity of Julius Caesar’s journeys: “He covered great distances with incredible speed, making a hundred miles a day in a hired carriage ... often arriving before the messengers sent to announce his coming.” Years later, according to Pliny the Elder, Tiberius “completed by carriage the longest twenty-four hours’ journey on record when hastening to Germany to his brother Drusus who was ill: this measured 182 miles.”

In her book The Roads to Rome, which explores how Roman roads have facilitated generations of human interchange, historian Catherine Fletcher writes: “the story of the Roman roads is the story of Europe and its neighbours, told from beneath our feet.” Much of that story lies buried now, overlaid with centuries of history, yet it continues to shape how people move, trade, and connect.

The art of bridge building

Wooden bridges

"He joined together at the distance of two feet, two piles, each a foot and a half thick, sharpened a little at the lower end, and proportioned in length, to the depth of the river. After he had, by means of engines, sunk these into the river, and fixed them at the bottom, and then driven them in with rammers, not quite perpendicularly, like a stake, but bending forward and sloping, to incline in the direction of the current of the river; he also placed two [other piles] opposite to these, at a distance of forty feet lower down, fastened together in the same manner, but directed against the force and current of the river. Both of these, moreover, were kept firmly apart by beams two feet thick."

Pontoon bridges

However, pontoon bridges were not all built for necessity—some were also built purely for propaganda purposes. In one of his many acts of megalomania, for example, Caligula ordered the construction of a two-mile pontoon bridge for horses and chariots to cross the bay between Puteoli and Bauli (modern-day Pozzuoli and Bacoli, in southern Italy). Ancient sources claim he staged a triumphal procession across the water dressed as Alexander the Great.

Bridge foundations

Arch design

Trajan's bridge over the Danube

Trajan’s Column and some surviving coins show the bridge over the Danube with wooden arches and a wooden parapet flanking the road on top. Some researchers think these pictures depict the bridge when it was under construction, while others believe they are proof that it was built of both stone and wood. But even such engineering triumphs could later have been used against the Romans. Cassius Dio explains that Trajan’s successor, Hadrian, “was afraid that it might also make it easy for the barbarians, once they had overpowered the guard at the bridge, to cross into Moesia (Roman territory).” In order to keep that from happening, Hadrian removed the superstructure, leaving only the mighty piers as a reminder of this awesome achievement.