How archaeology is unraveling the secrets of WWI trench warfare

Lasers and aerial photography are helping uncover the hidden stories of the Great War.

World War I was the planet’s first global industrialized conflict, and the use of new technologies like planes, armored tanks, machine guns, grenades, and poison gas resulted in unprecedented devastation. Between 1914 and 1918, more than eight million military personnel died and more than six million civilians were killed. But the statistics that really astonish archaeologist Birger Stichelbaut are the ones that show how deeply the landscape was transformed in parts of Europe: A 37-mile stretch along one 420-mile front line in Belgium, for instance, was shot through with more than 3,000 miles of trenches.

"Those are huge numbers," Stichelbaut says.

Stichelbaut, of Ghent University in Belgium, is among a small group of archaeologists investigating those physical marks that remain from the Great War more than a century later. While the conflict was documented in thousands of first-hand written accounts, photographs, and film reels—and subject to countless post-war assessments—archaeology still adds another dimension to our understanding of one the most violent conflicts in modern history.

"All the people who actually witnessed the First World War have all passed away," says Stichelbaut. "The landscape today remains the last witness."

Bird's-eye view of war

Some of the worst fighting in World War I occurred along the Western Front in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, where Allied troops and German forces launched deadly attacks from their respective trenches. The region became a moonscape during the four grinding years of battle, but post-war reconstruction occurred rapidly. Many traces of the war were left intact, and are often buried less than a foot below today's surface.

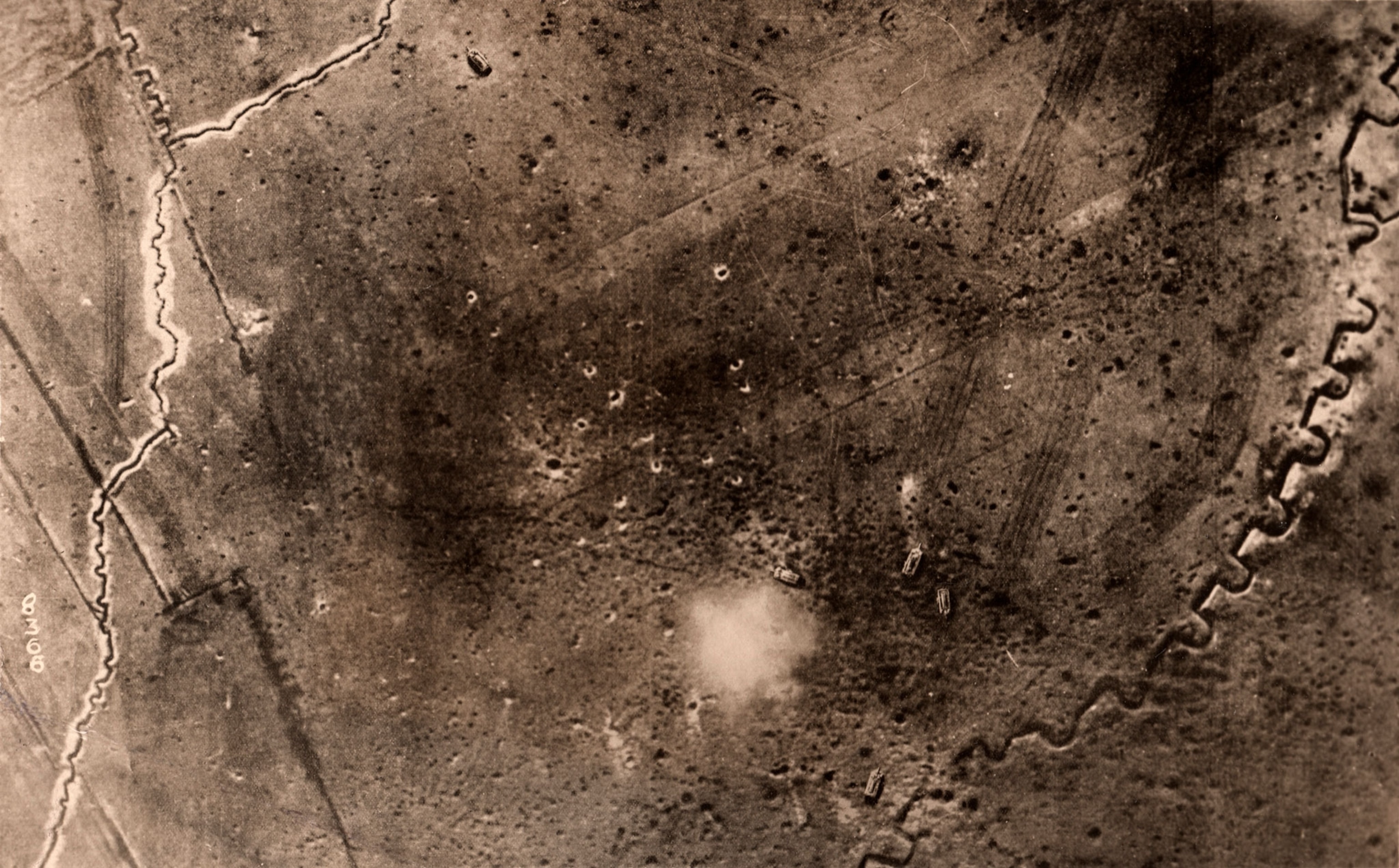

To understand how this warscape developed, and what sites remain, Stichelbaut and other researchers use aerial archaeology. World War I saw aerial photography as a new tool for surveillance on enemy positions, and now thousands of these historical images comprise the oldest aerial records for the region. Stitched together, they offer a bird's-eye view—more accurate than contemporary maps made on the ground—of how trenches and other military installations were constructed and changed over time.

Explore the memorials of World War I.

To complement the historical images, archaeologists rely on modern aerial imaging. Cropmarks captured in photographs during periods of drought can provide stunning maps of buried century-old trench networks, where water pools under today's farmland. In the last ten years, archaeologists have also been employing LiDAR, a technique that uses lasers to "see" through surface vegetation.

LiDAR surveys reveal just how much of the landscape in Western Europe is still marked by zig-zag trenches, shelling craters, and other remnants that may not be obvious on the ground. For example, LiDAR images from a stretch of the Western Front between Kemmel and Wervik in Flanders reveal that 14 percent of the land—more than expected—is still visibly scarred by the war, according to Traces of War, a book Stichelbaut compiled to accompany an exhibit last year at the Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres.

In using historical and modern aerial images, "you suddenly get a different perspective, you're seeing the totality [of the war], you're seeing patterns and you're seeing sites that even if you would be standing on the site today, you wouldn't see that it's a trench," Stichelbaut says.

Trench waders and teddy bears

Aerial images can guide excavations, and when archaeologists actually dig, they learn about forgotten aspects of soldiers' everyday experience.

"There were not many photographs taken in the trenches," Stichelbaut says. "So what archaeology really does is give you a snapshot of what life in the trenches was really like."

The archaeology of World War I sites has especially helped scholars understand how soldiers improvised their trench construction to cope with harsh conditions.

"You can read as many First World War manuals of how to dig a trench as you like, but always if you look into the archaeology, you will see the reality of trench warfare on the ground," Stichelbaut adds.

The region's waterlogged soil helps preserve organic materials like wood and textiles—a boon for today’s archaeologists. But more than 100 years ago, soldiers were in a constant battle against that water and mud. Many trenches were mistakenly dug below the water table. As the seasons changed and rain fell, life could become miserable for soldiers, even when they weren't under fire. Trench foot, caused by cold, wet, dirty conditions, led to 75,000 British casualties.

A British soldier who spent time in the network of tunnels known as "Hades Dugout" below the town of Wieltje, near Ypres, wrote that after a descent down more than 30 slippery steps, one would reach the bottom of the shelter and "stand in a black and slimy river, slowly moving onwards and disappearing in the darkness, revealed by some weary-looking electric lights."

"Is it the Styx, you ask? Anyway, it stinks," the soldier wrote in an account featured in Traces of War.

Archaeologists at Wieltje found more rubber trench waders than standard soldiers’ boots. Excavations of other trench networks in Belgium show that soldiers were using straw, rubble, roof tiles, and doors in an effort to keep their feet from sinking into the morass.

These subtle details help create a fuller picture of the soldiers' experience. For Stichelbaut, some of the most moving discoveries are trench art: Engravings, bullets cut and hammered into crucifixes, and other objects that show how troops were spending their anxious downtime.

A discovery that sticks with archaeologist Simon Verdegem is a German backpack with a teddy bear inside, found near the Belgian village of Langemark during the construction of a gas pipeline.

"You find a lot of artifacts that tell the personal stories of soldiers that would otherwise never be brought to light, that bring humanity to the soldiers," the archaeologist says.

Verdegem specializes in World War I for the Belgian commercial archaeology firm Ruben Willaert. He recently got a chance to peer inside a massive trench system at Wijtschate, a town along the Messines Ridge outside of Ypres, during a recent archaeology project called Dig Hill 80.

The excavation, which took place in 2018 and is still being documented, revealed buried trenches and the remains of farm houses abandoned during the war. Verdegem says he was surprised that most of the archaeological remains discovered at Wijtschate dated to a little-known battle that took place in 1914, rather than a major battle that occurred in 1917 when Allied troops launched a surprise attack on Wijtschate to retake a German stronghold.

The Dig Hill 80 crew also uncovered the remains of more than 130 soldiers of various nationalities at Wijtschate. World War I archaeology may be most different from the archaeology of previous periods in that living families are still impacted by the discoveries made in the trenches.

"There are entire generations in several countries that are still wondering what happened to their ancestors during the war," says Verdegem. "Now and then we're able to give them an answer, so that's a special thing."

Unfortunately, those answers are still mostly difficult to come by. Verdegem estimates that he's personally excavated the remains of about 200 soldiers. Of those, only three have been identified.