These manuscripts brought the fantastic beasts of the Middle Ages to life

Among the most popular books of the time, bestiaries were filled with real and mythical animals and their lore, the protagonists of intriguing stories symbolizing human virtues and faults.

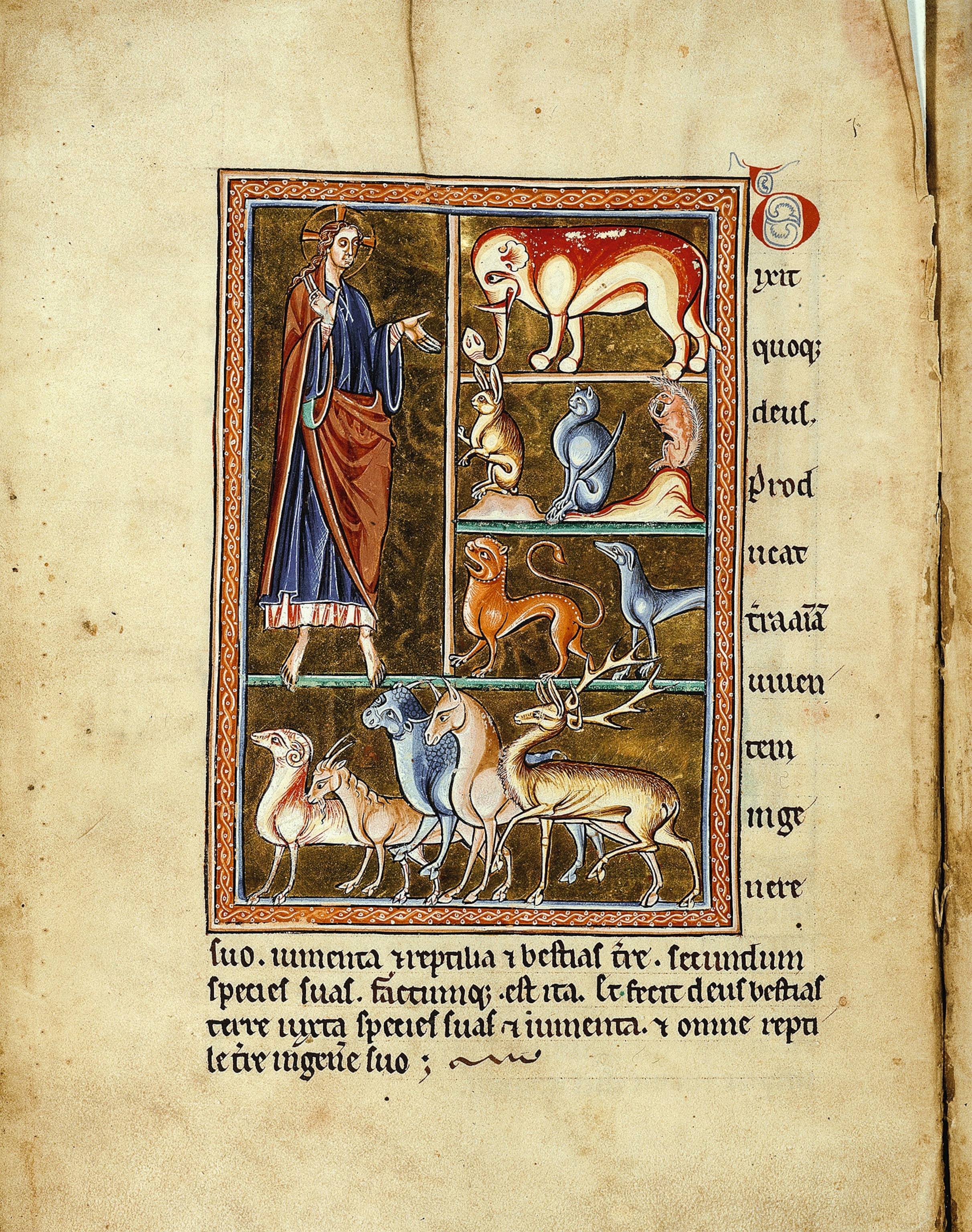

In the second or third century A.D., an anonymous author in Alexandria, Egypt, composed a text entitled Physiologus, or The Naturalist. The work was soon widely copied and comprised of 48 or 49 chapters. Each was dedicated to a specific animal and included an illustration, a description of its characteristics, and a story—part natural observation, part imaginative anecdote—about its behavior.

One such story, for example, features the lion. It was said that lion cubs were born lifeless and watched over by their mother until the father, king of the beasts, arrived and breathed life into them. This image gave rise to an allegorical reading steeped in Christian symbolism: the cub revived by the lion became a figure of Christ resurrected on the third day. While the lion embodied noble virtues, other creatures served as warnings. The hedgehog, for instance, was believed to climb into vineyards, shake down the grapes, and then impale them on its spines to carry back to its young. According to the Physiologus, this was a cautionary tale: a call for Christians to guard the vineyard of their souls. “You, O Christian, refrain from busying yourself about everything, and stand watch over your spiritual vineyard from which you stock your spiritual cellar... Do not let concern for this world and the pleasure of temporal goods preoccupy you, for then the prickly devil scattering all your spiritual fruits will pierce them with his quills and make you food for the beasts.”

Such examples illustrate the core intent of the Physiologus: use the animal world as a moral mirror that reflects human passions, vices, and virtues. Beneath the surface of each tale lay a didactic message grounded in early Christian doctrine. The stories were born from the belief that animals were created by God at the beginning of time as instruments of instruction for humankind.

(What was a drugstore like in medieval Europe?)

Spread of the bestiaries

The Greek Physiologus was translated into Latin and other languages during the fourth and fifth centuries. Over time, it was expanded with material drawn from influential works, including Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies, Ambrose of Milan’s Hexaemeron, and classical sources on natural history—Aristotle, Herodotus, and Pliny the Elder.

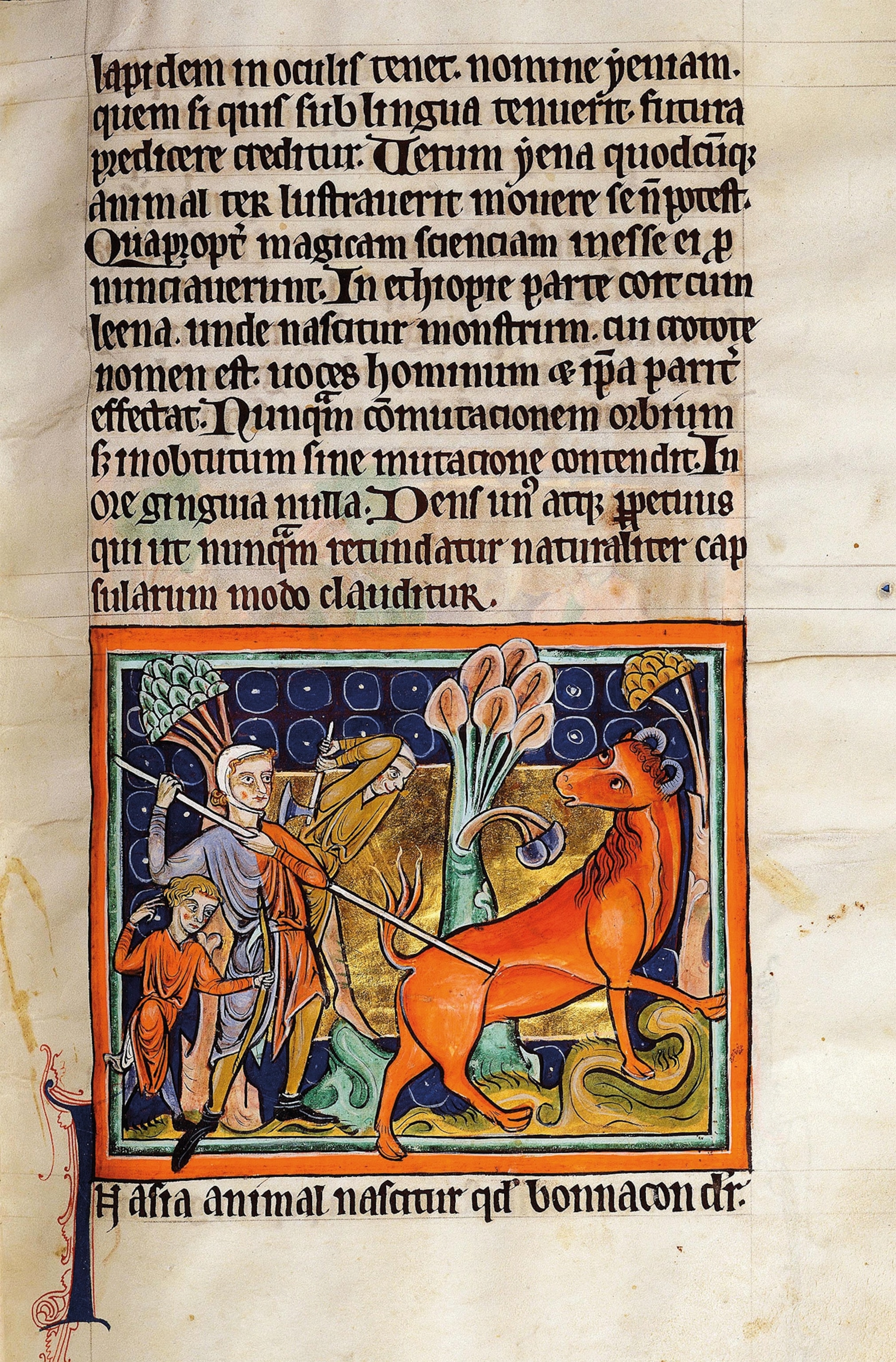

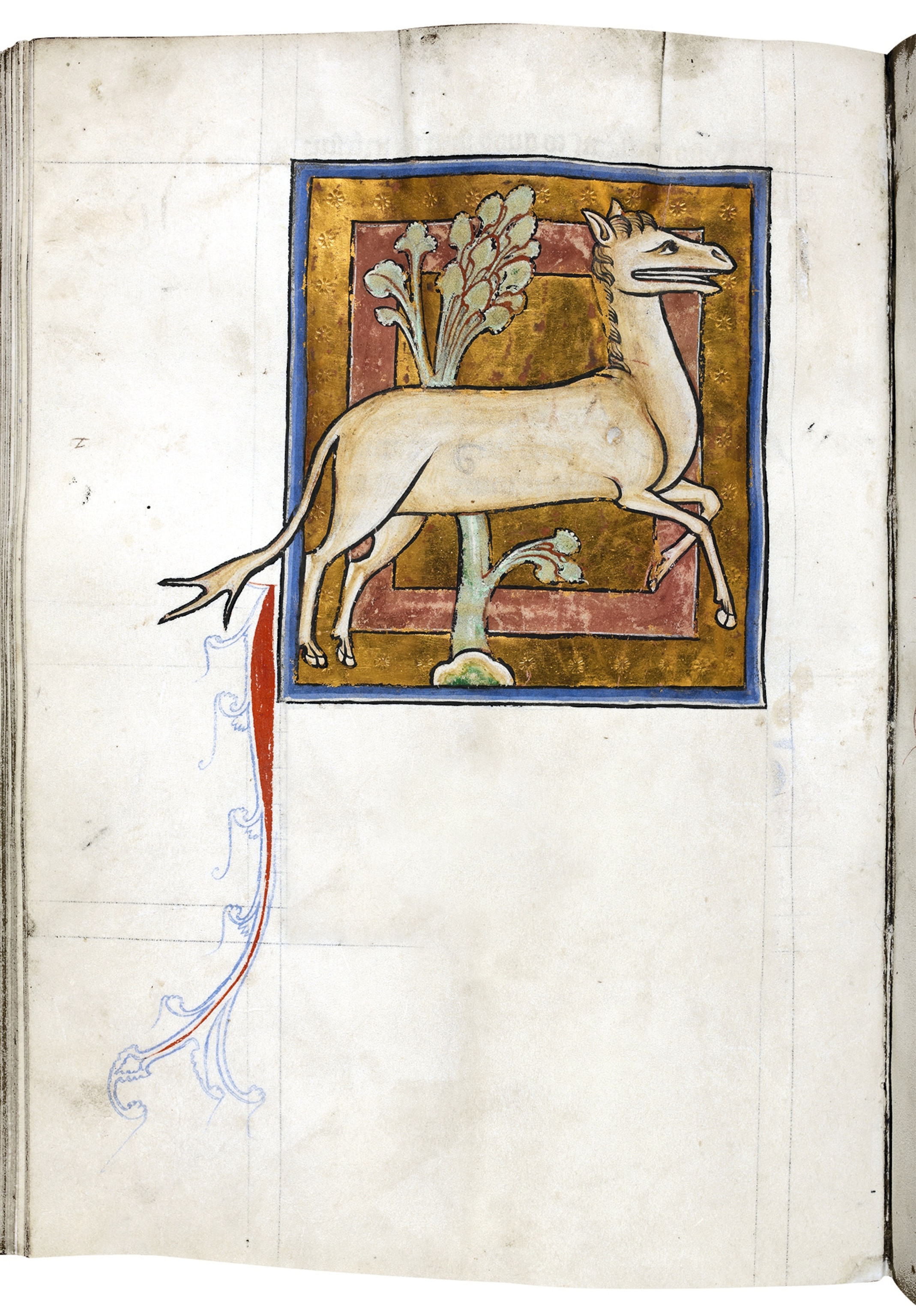

By the high Middle Ages, the text had made its way through Western Europe under the Latin title Liber Bestiarum or simply Bestiarum. Between the 12th and 14th centuries, it was translated into numerous vernacular languages. Most versions were richly illustrated with miniatures—some of exceptional delicacy and craftsmanship—depicting the full menagerie of animals described in the text.

The symbols and iconography of the bestiaries were not confined to the page. The creatures in these manuscripts also migrated to stone and wood, appearing on the façades of churches and cathedrals, in the carved capitals of cloisters, and even in the interior decoration of secular and aristocratic homes. In one 13th-century residence in the French city of Metz, the ceilings of two rooms were adorned with a complete bestiary—an ensemble that survives today in the local museum.

A motley menagerie

Although not a zoological treatise in the modern sense, the bestiary captured the sum of medieval knowledge about the animal world. Many of the animals it described were part of everyday life. The crucial domestic role symbolized by horses and dogs earned them long entries, often highlighting their loyalty and intelligence. One tale recalls how the horses of Charlemagne and Gaius Caesar accepted no rider but their masters. Another tells of King Lysimachus of Thrace’s dog, which leaped into his master’s funeral pyre, refusing to be parted even in death.

Bestiaries also featured animals considered exotic by European readers, such as lions, elephants, apes, and ostriches, native to Africa and Asia. Artists rarely saw these creatures firsthand, so they relied on written descriptions or copied earlier drawings.

(How would you draw an elephant if you’d never seen one?)

Alongside the familiar and the exotic were imaginary beasts said to inhabit distant lands. Some drew authority from ancient sources or biblical texts. The ant-lion, for instance, was believed to be born of a lion and an ant, a confusion that may have arisen from a mistranslation of a passage from the biblical Book of Job. The New International Version translates this passage as “the lion perishes for lack of prey, and the cubs of the lioness are scattered” (Job 4:11). In the Septuagint, the third to second-century B.C. Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Hebrew word for lion— layish—is rendered as mermecolion, “ant-lion.” The mistake was possibly caused by either a poor understanding of Hebrew or a transcription error. Still, such a creature now existed in the imagination of scholars: according to the Physiologus, “It had the face (or forepart) of a lion and the hinder parts of an ant.”

In older translations of the Bible, the word “unicorn” also appears, such as in this passage from the King James Version of Psalm 22:21: “Save me from the lion’s mouth: for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns.”The decision of the translators to render the Hebrew word re’em as unicorn could have been influenced by scholars’ knowledge of the mythical animal from Indian sources. Modern Bible translations, such as the New International Version, render re’em as “wild ox.”

Other fantastical beings came from classical tradition. Sirens—hybrids of woman and bird or fish—and the phoenix, a bird that immolated itself and rose from its ashes on the third day, echoed themes of renewal and divine mystery.

(How dragons lost their wicked menace—and became our friends)

From a modern perspective, it is easy to distinguish fact from fable. But for medieval readers, such distinctions may not have mattered. Their knowledge of distant animals came from texts, not observation, and bestiaries were never intended as scientific manuals. Real or imagined, these creatures represented God’s creative power and were part of a sacred natural order designed to teach spiritual truths.

Fantastical birds

Fabulous equids

Dragons and reptiles

Half animal, half human