How a doomed bridge became the Pacific Northwest’s most unlikely reef

After Galloping Gertie collapsed in 1940, its twisted steel created a thriving underwater world. Now it’s at risk.

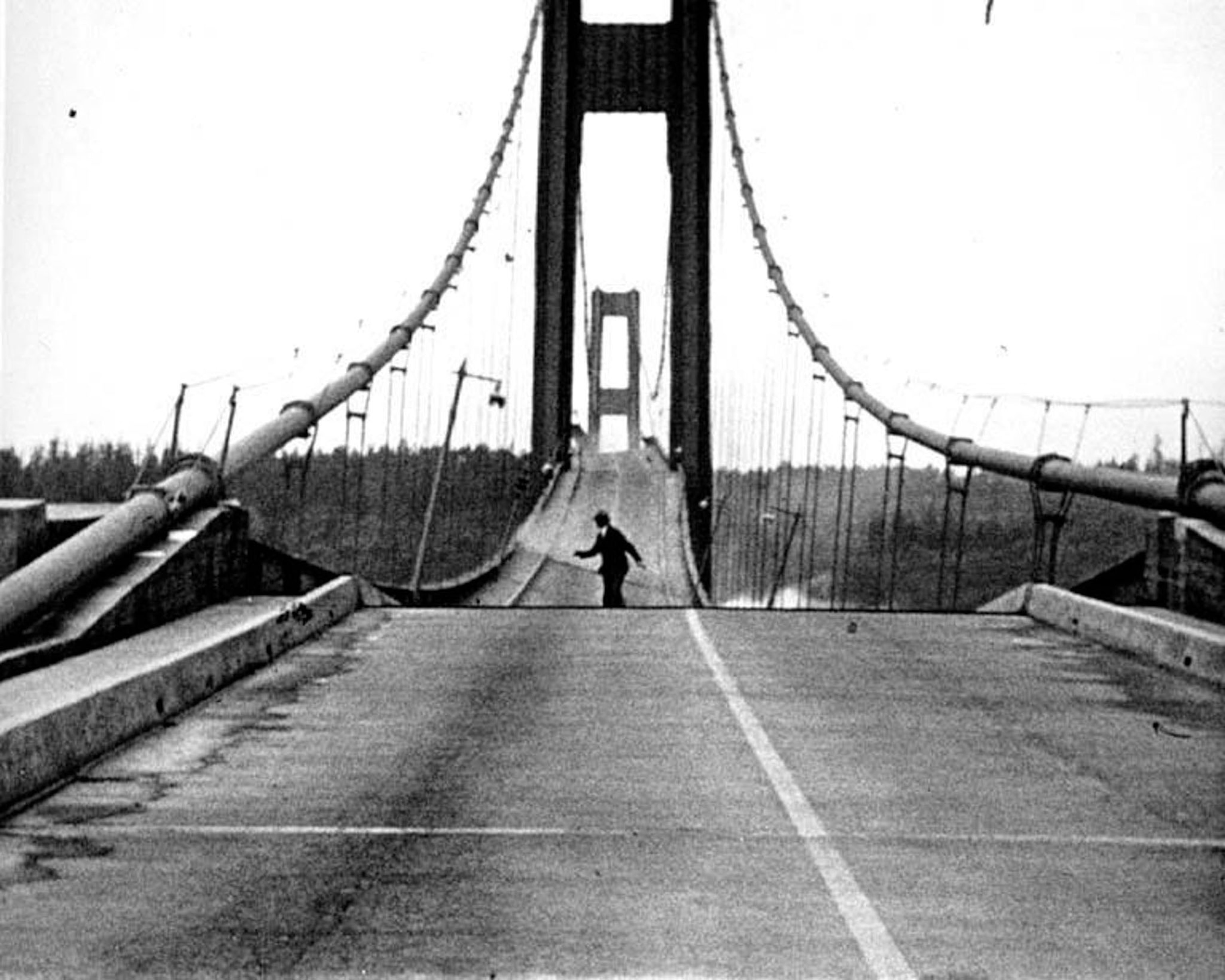

When the two-lane Tacoma Narrows Bridge opened on July 1, 1940, it was hailed as a “triumph of structural engineering.” Locals quickly gave it another name—Galloping Gertie—after noticing how the roadway bucked and rolled even in light winds. Drivers reported the bridge rising and dipping enough to hide cars in the next lane momentarily.

Four months later, on the morning of November 7, 1940, sustained winds of roughly 40 miles per hour caused Gertie to twist apart and collapse. No human lives were lost.

The failure helped reshape bridge design and wind-tunnel testing for decades, but what’s less known is what happened after the wreck sank into Puget Sound.

On the seafloor, the fallen bridge has become one of the largest artificial reefs in the Pacific Northwest. Divers describe steel beams draped in anemones, wolf eels coiled through twisted girders, and octopuses sheltering inside collapsed sections of roadway.

Now, as marine life declines in Puget Sound, this accidental ecosystem may be in danger—and its legacy is more important than ever.

The collapse that changed engineering

Upon its completion in 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge was expected to bolster the economy and serve as a key military route, linking McChord Air Force Base near Tacoma with the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington. At the time, it was the third-longest suspension bridge in the world.

But the push for elegant, lightweight bridge designs during the Great Depression meant Gertie relied on relatively shallow girders— a cost-saving choice that reduced the bridge’s stability.

When steady winds funneled through the narrow channel on November 7, 1940, the deck entered a twisting motion known as “torsional flutter,” swinging nearly 45 degrees before tearing apart. The dramatic collapse, captured on film, shocked engineers worldwide and became a defining cautionary tale in structural design.

(These 12 stunning bridges are engineering marvels.)

The investigations and studies that followed reshaped national bridge-design standards. Aerodynamic modeling and wind tunnel testing became common practice for modern suspension bridges. A wider, four-lane replacement bridge, dubbed “Sturdy Gertie,” was rebuilt by 1950. With heavier cables and open wind grates, it was stronger—and more stable—than its predecessor. A new eastbound span of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge later opened in 2007.

An unexpected second life

After the collapse, tons of steel, concrete, and cable sank to the seafloor. In subsequent decades, the remnants of Galloping Gertie, some more than 200 feet beneath the surface of the Puget Sound, evolved into what the Associated Press once called a “barnacle-encrusted reef teeming with marine life.”

“Any time you have an area where things can attach to it, you’re going to have more and more sea life if there’s no intervention,” says Peter Bortel, producer of the 2021 documentary “700 Feet Down,” which explores the collapse and Gertie’s transformation into an artificial reef. Reaching the wreckage requires careful planning, largely due to strong currents.

In the documentary, divers found octopus and wolf eels tucked into concrete dens, along with barnacle-coated rubble surrounded by rockfish and kelp crabs. Heidi Wilken, diving safety officer at the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium in Tacoma, has been on roughly 10 dives to the area since the early 2000s and recalls once seeing pieces of roadway “absolutely covered with anemones.”

“It’s good to remember…that the ocean makes everything that ends up in it, its own,” adds Wilken.

The site’s rich biodiversity fed into the beloved local legend that a 600-pound “King Octopus” lived beneath the bridge. While no such giant has ever been documented, divers have spotted giant Pacific octopus—the largest octopus species on Earth—and smaller East Pacific red octopuses.

“That legend of the octopus under the bridge is so prolific in the Pacific Northwest,” says Carly Vester, director of “700 Feet Down.” “I grew up crossing the bridge, being told the world’s largest octopus lived underneath it.”

A threatened ecosystem

Now, decades after those stories took root, the ecosystem is showing signs of steep decline. Bortel says he’s dived by the site hundreds of times since the 1990s, when the wreckage was a “beautiful, elaborate ecosystem with wolf eels, octopus, rock cod and lingcod everywhere.”

The ruins still support a range of species, says Bortel, who last dove the Narrows in August 2025. But “now, in my 50s, pretty much all I find is fishing lures, and a couple rockcod; most of the wolf eels and octopus have moved on,” he says. “The fish are smaller, and I would say 90 percent of the marine life is gone from what it used to be 30 years ago.”

(Shipwrecks may help tropical fish adapt to climate change.)

He believes the primary reason is overfishing and adds that rockfish have surpassed giant lingcod as the site’s most abundant species. However, even certain rockfish varieties and other fish species in the Puget Sound have diminished in the past several decades. Meanwhile, marine life is more plentiful in the shallower areas under the current bridge, where fishing is less common, Bortel says.

“If no one knew that the bridge had collapsed and it was just down there and no one was fishing it, it would be the most amazing marine environment that we’d have in the Puget Sound,” Bortel says.

Divers and local historians have long sought to protect the wreckage. In the early 1990s, such efforts successfully led to the site’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places, protecting it from salvage divers and preserving it as an engineering artifact and an ecological refuge.

The official nomination to add the bridge’s wreckage to the register described it as a “permanent record of man's capacity to build structures without fully understanding the implications of the design and the forces of nature.”

Today, some advocates hope the site may one day become a designated marine reserve, preserving a chapter of engineering history and the accidental ecosystem it created.