Coronavirus upended Notre Dame’s future. WWII may have some answers

Plans for the beloved cathedral’s reconstruction have been disrupted by the pandemic. But Europeans have faced a similar situation before.

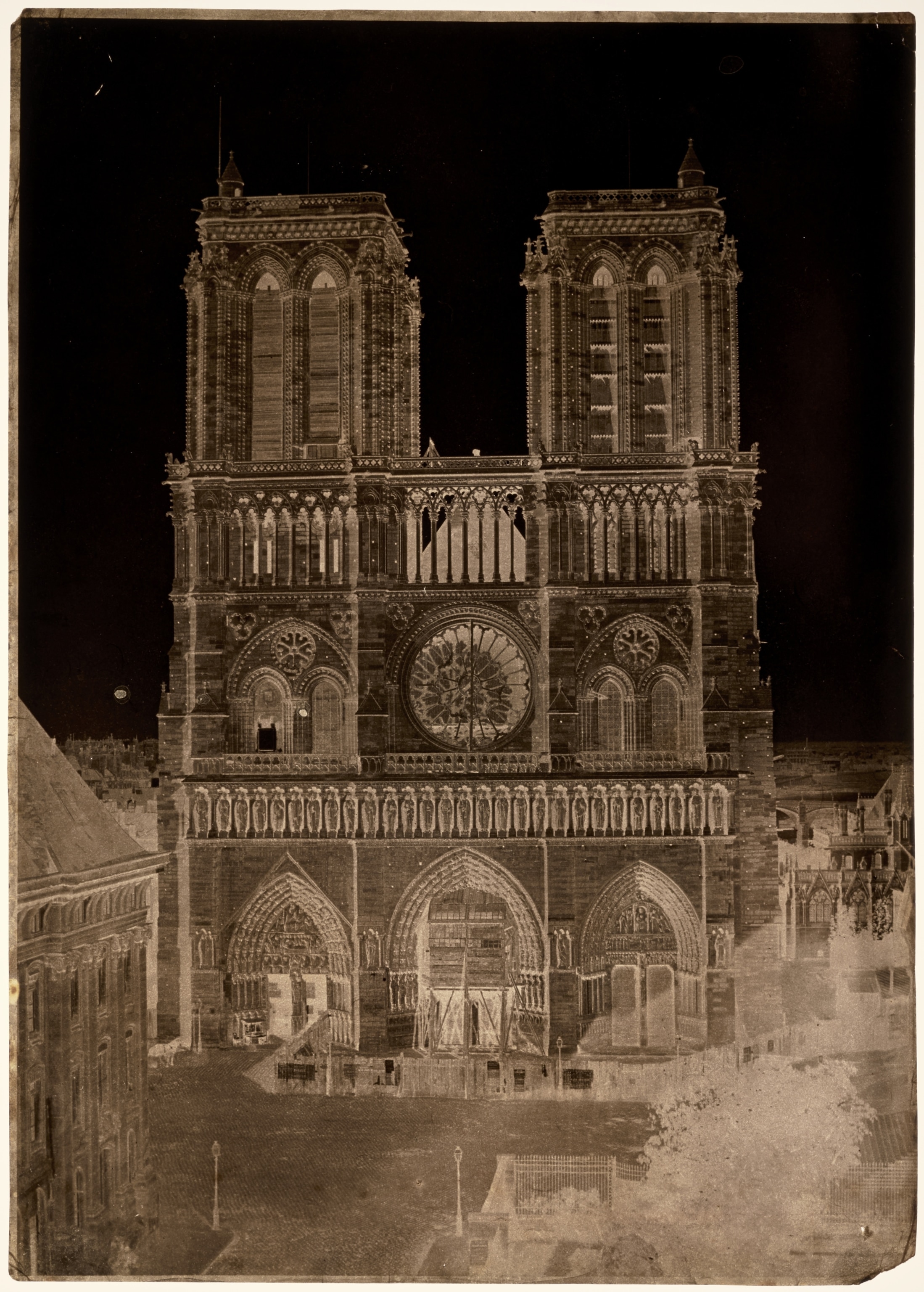

At the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, it was already a Good Friday unlike any in modern memory: The spring-day sun poured down into the roofless nave as celebrants wore hard hats to shield themselves from falling debris and disposable coveralls to protect against lead contamination. Nonetheless, the Good Friday veneration of the Crown of Thorns—the prized relic brought to Notre Dame from the Holy Land by Louis IX in the 13th century—continued as it had for hundreds of years.

It was just the second service to be held in the fragile remains of the cathedral since the fire that destroyed its iconic spire and much of the roof of the cathedral nearly a year ago. But unlike the mass attended last June by dozens of people to mark the two-month anniversary of the conflagration, this time there was only a handful of socially-distanced celebrants in Notre Dame. In addition to the protective hard hats, several of the celebrants also wore surgical masks to stem transmission of a virus that had to date infected more than 100,000 French citizens and killed at least 12,000.

This was the first Good Friday to be celebrated in the fire-damaged spiritual heart of Paris, but it was also the first Good Friday of the coronavirus pandemic. The words of Michel Aupetit, the Archbishop of Paris, seemed to carry even more freighted meaning as they rose from the makeshift altar inside Notre Dame and into the springtime sky:

“Today we are in this half-collapsed cathedral to say that life is still here.”

An uncertain future

The fate of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris has become even more perilous in the weeks following the lockdown of France in response to the threat of COVID-19. There were already estimates in 2019 that the structure had a 50% chance of additional partial or total collapse. And a course of rapid reconstruction—initially projected by President Emmanuel Macron to be completed in time for the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris—had already been delayed due to the painstaking work required to remove the toxic remains of its lead-tiled roof. Then there was the matter of the 21st-century construction scaffolding, a heat-warped mass of metal perilously perched atop the damaged structure and slated for removal beginning at the end of last month.

Discover why many historic icons face same threats as Notre Dame.

But since March 16, all work at Notre Dame has stopped in response to the pandemic. The damaged cathedral, cordoned off from the community it helped sustain for centuries, is bereft of its hazmat-suited lead abatement team and the daring, abseiling crew—fondly known as “squirrels”—who are tasked with the tricky scaffolding removal. Engineers now warily eye remote laser monitoring systems that can detect any structural movement that may predicate the collapse of the Gothic masterpiece, while security guards patrol its perimeter. Thieves have already taken advantage of the lockdown to attempt to spirit away building blocks of the sacred structure.

“I’m so worried about the security of everything [at Notre Dame],” says Lindsay Cook, who teaches medieval art and architectural history at Vassar College. “All you’ve been hearing so far for the last few months is that this is still a very fragile situation. And to just leave it there seems like it’s just asking for trouble over time.”

Reconstruction during difficult times

How might we know when the reconstruction of Notre Dame cathedral eventually be completed, and what the end result might look like? In a world where every day norms seem to shift and dissolve from week to week, it’s impossible to say. But the fate of another iconic cathedral partially destroyed by fire during World War II may be instructive.

Read National Geographic’s 1968 ode to Paris' most famous cathedral.

Like Notre Dame de Paris, Cologne Cathedral in Germany is a towering Gothic cathedral that has been both the spiritual heart of a grand city and a revered national symbol. Its construction on the bank of the Rhine River began in 1248, just 85 years after the foundation stone for Notre Dame was laid in the soil of Paris’ Île de la Cité. Originally modelled after another grand French Gothic cathedral, construction on Cologne’s main house of Catholic worship went in fits and starts until work was abandoned during the 16th century. And, like Notre Dame, the Cologne Cathedral received renewed appreciation and reconstruction during the Gothic Revival of the 19th century, when it became a towering symbol of German ambitions past and present. For a few years in the 1880s, Cologne Cathedral was the tallest building on the planet, and still remains the tallest twin-spired church (at 515 feet) in the world.

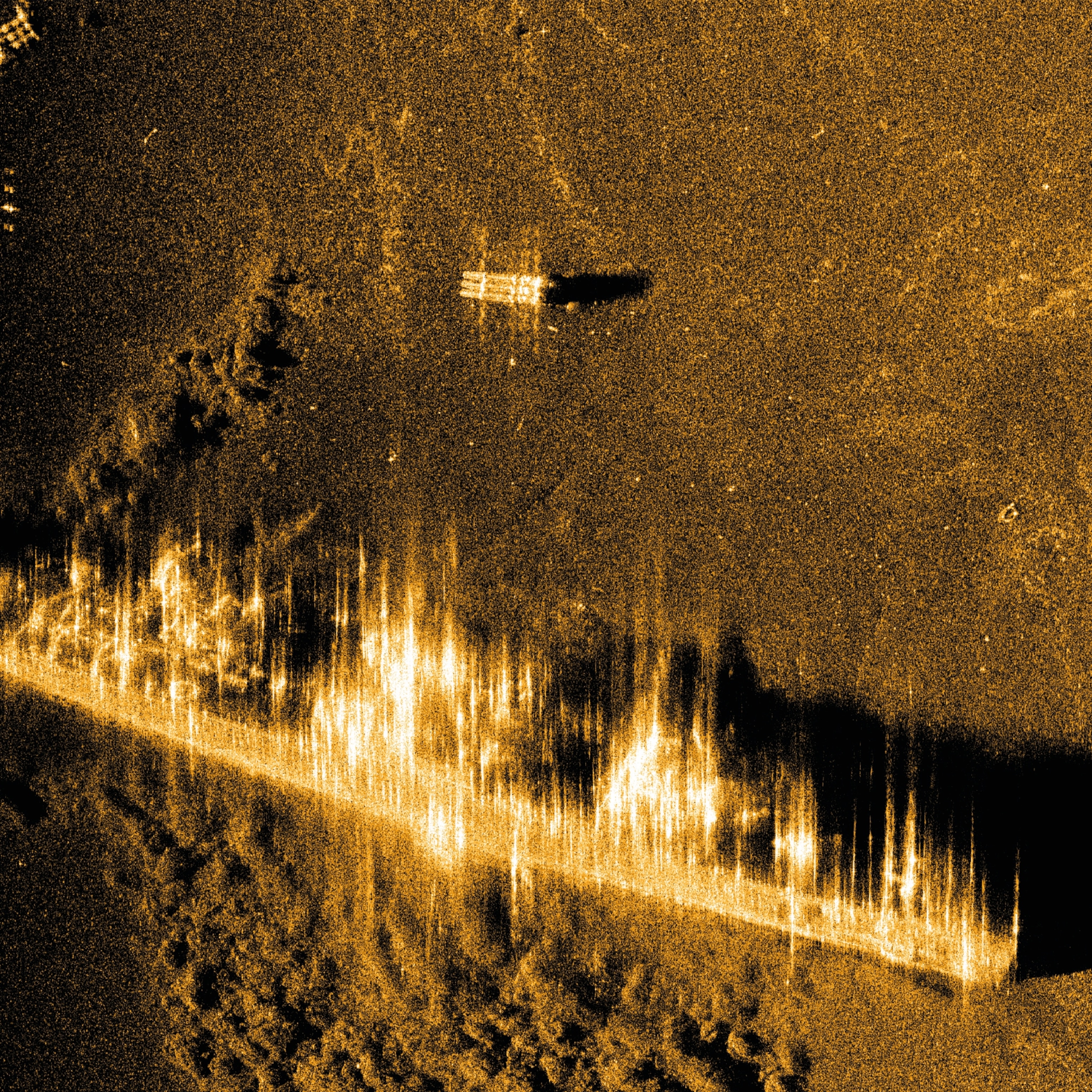

But unlike Notre Dame de Paris, which escaped most damage during WWII –despite the French capital being subject to aerial bombing by both German and Allied forces—the Cologne Cathedral was hit 14 times by American and British aerial bombing raids between 1942 and 1943. By the end of the war, 90 percent of Cologne’s city center was in ruins, with just the city’s cathedral, now roofless and pockmarked by bullets, rising from the center of an otherwise leveled city.

The post-war fate of Europe’s damaged cathedrals varied depending on geography, politics, and extent of destruction: The ruins of Britain’s Coventry Cathedral, for instance, were left unrestored and incorporated into a modernist house of worship as a reminder of the ravages of war. In the eastern half of Europe that ended up behind the Iron Curtain, many damaged Gothic churches, such as Dresden’s Sophienkirche, were considered symbols of a pre-war, pre-Socialist past, and simply bulldozed.

Learn how lasers can unlock the mysteries of Gothic cathedrals.

In a defeated and occupied western Germany immediately after the war, reconstruction efforts varied from city to city. The citizens of Cologne, backed by a wealthy diocese and funding from the international Catholic community, chose to make the reconstruction of their cathedral a priority. By 1948—before the creation of a national German government or the arrival of the Marshall Plan—the principal apse of the Cologne Cathedral, where the high altar is located, had been rebuilt in celebration of the building’s 700th anniversary. By 1956, just 11 years after the end of WWII, masses were being conducted beneath the cathedral’s reconstructed nave.

Unlike the hasty stabilizing work performed on the Cologne Cathedral in the first decade following the war, the rebuilding of Notre Dame will be guided by a series of cultural heritage conventions adopted by the international community in the years and decades following WWII. These conventions meticulously prescribe the methods and materials that should be used in modern restorations, making Macron’s five-year rebuilding plan—or even a 10-year-plan—extremely unlikely. Even the current chief architect of Cologne Cathedral, in the days following the Notre Dame fire, opined that the reconstruction of the beloved French cathedral would likely take decades.

Another big question is how France and the European Union will choose to allocate their resources following the coronavirus crisis, predicted to result in the sharpest economic downturn since WWII. Will the nearly 900 million euros pledged in the days after the 2019 fire fully materialize? And will calls for strengthening the social safety net push the cathedral’s reconstruction efforts into the background?

According to Sheila Bonde, a professor in medieval art history, architecture, and archaeology at Brown University, this is the same question many European nations faced when dealing with destroyed houses of worship after both World War I and World War II. “Do you rebuild the heart of a town by rebuilding its symbolic center, or are funds needed for social services?” Bonde asks. “I think some very hard decisions are going to have to be made to balance those needs.”

Finally, what role will a renewed Notre Dame cathedral play in a post-COVID-19 Europe? Astrid Swenson, a professor of history at Bath Spa University who has written extensively on the history of Cologne Cathedral, notes how the cathedral, a symbol of German nationalism up through the Nazi era, was rebranded after WWII as a symbol of pan-European revival following a war that tore the continent apart.

Only time will tell if a renewed Notre Dame de Paris will serve as a unifying force for a European Union emerging from the coronavirus crisis, or as a symbol of French pride and exceptionalism cresting a wave of nationalism that had already begun to fracture the EU long before the coronavirus crept inside its borders.

“I don’t know whether the timing of the reconstruction [of Notre Dame] matters, and whether these great ways of how architecture in the past could be rebuilt and used to give new symbols,” Swenson muses. “It could happen after the pandemic, or there could be more focus on social justice. I don’t know if these same mechanics that we’ve seen in the past can be reproduced.”

Swenson pauses, then sighs. “Historians are so bad at speculating, aren’t they?”