Hints of Skull Cult Found at World's Oldest Temple

Carved human skull fragments from a Stone Age archaeological site hint at a surprisingly complex culture.

Around 10,000 years ago, the already striking presence of Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey could have been even more impressive—as human skulls might have dangled in what is considered the world's oldest temple.

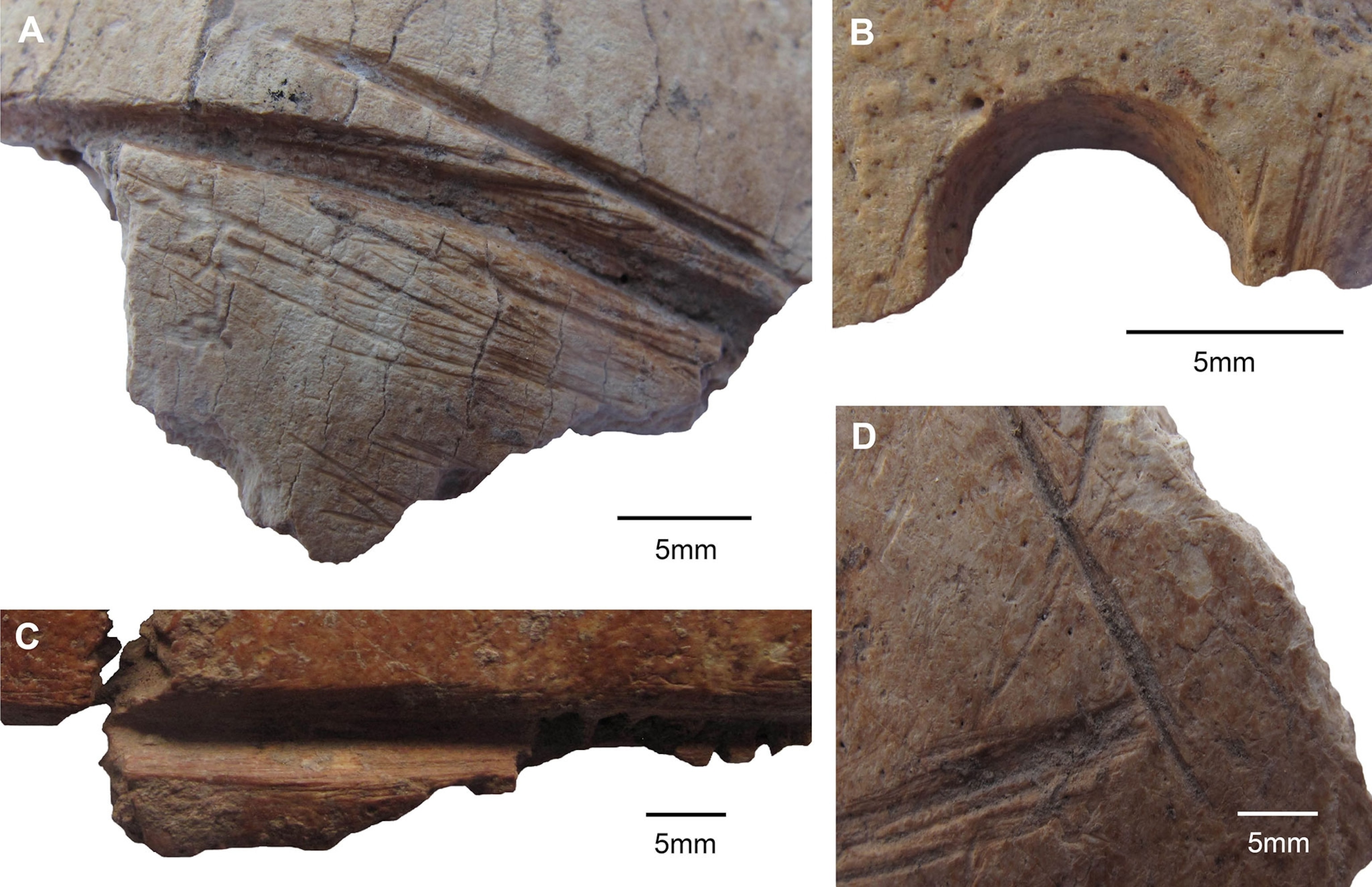

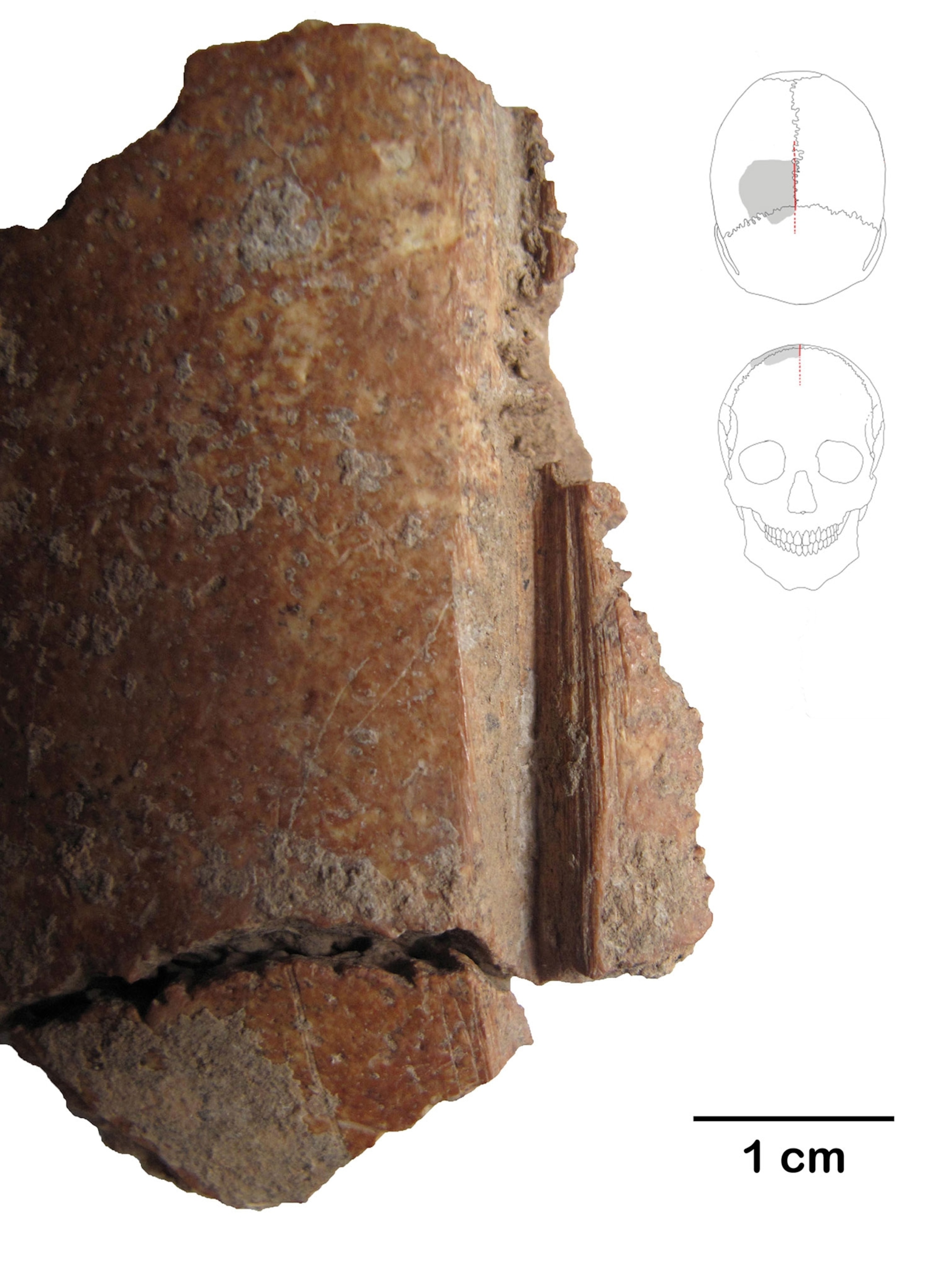

According to new research published in Science Advances, three Neolithic skull fragments discovered by archaeologists at Göbekli Tepe show evidence of a unique type of post-mortem skull modification at the site.

(Read more about Göbekli Tepe, the "world's oldest temple.")

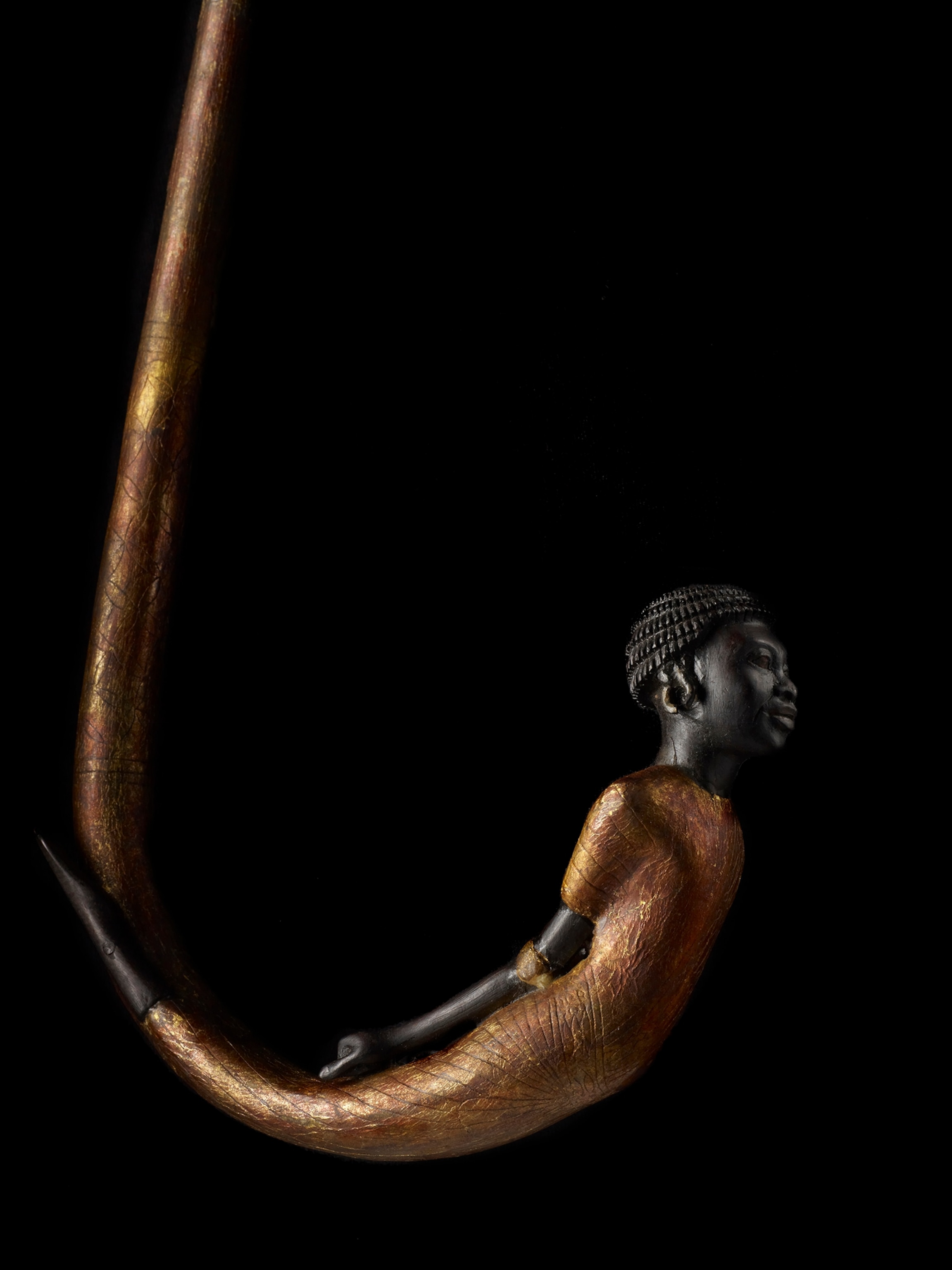

The deep, purposeful linear grooves are a unique form of skull alteration never before seen anywhere in the world in any context, says Julia Gresky, lead author on the study and an anthropologist at the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin. Detailed analysis with a special microscope shows the grooves were deliberately made with a flint tool. One of the fragments even has a hole drilled in it, resembling skull modifications made by the Naga people of India who used the hole to hang the skull on a string.

The marks may only appear on a few fragments of bone that date between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago, but archaeologists believe that this find is extremely significant and means that this society, like many others in this part of the world at the time, was a “skull cult” that venerated the human skull after death.

SKULL AND BONES

“Skull cults are not uncommon in Anatolia,” says Gresky. She explains that archaeological remains from other sites in the region indicate people would commonly bury their dead, then exhume them, remove the skulls, and display them creatively. Other archaeologists have even found that Neolithic people would remodel the faces of the dead with plaster.

(See the face behind the 9,500-year-old plastered Jericho Skull.)

Göbekli Tepe held special significance to the Neolithic people who lived nearby. “This was not a settlement area, but mostly monumental structures,” the anthropologist explains.

The site's massive T-shaped stone pillars and prominent position on top of a hill with sweeping vistas suggests the hunter-gathers who lived here also had a somewhat complex culture and practiced rituals.

FRIENDS OR FOES?

“This is an interesting skull modification that hasn’t been documented in this part of the world or this time period,” says bioarchaeologist Matthew Velasco at Cornell University, who was not involved in the study. But this find does raise additional questions about who the skulls belong to and why they were treated this way.

“There is a range of skull modification behaviors, [from] veneration of ancestors to violation of enemies,” Velasco explains, and this distinction can only be investigated at Göbekli Tepe if additional discoveries are made.

Besides the cut-mark and drill-hole evidence, Gresky says other clues at the site show this culture placed a special significance on skulls. “We find depictions like a headless person on a pillar, or human heads made of stone. The site iconography fits with special emphasis on the skull.”

At Göbekli Tepe, there are no burial sites but rather just pits of human bones mixed in with animal bones and flint tools, meaning additional context is needed to better understand the site. “We are still in the beginning of working to understand the anthropology of the site," says Gresky. "[H]opefully we will find some more bones and skull fragments. Then we can get a clearer picture of how these people lived.”

Follow Shaena Montanari on Twitter.