Nigeria's ancient royal portraits challenged European biases toward African art

Nearly a thousand years ago, Ife artisans sculpted bronze and terra-cotta heads, whose realism and beauty would astound the first Europeans to see them in the 1900s.

The Yoruba people of Nigeria believe Ife to be a sacred city founded by the gods and the birthplace of humanity. Lying 135 miles northeast of the Nigerian city Lagos, Ife was where archaeologists uncovered a series of sculptures that revealed a rich yet overlooked history of Yoruba culture to the world.

While some were made of metal and others of terra-cotta, the heads of Ife share a highly symmetrical style. Some faces are adorned with lines and designs, and elaborate hair styles top their heads. All convey a dignified and imposing majesty.

The importance of the human head in the Yoruba cosmology was unknown to the German ethnologist Leo Frobenius, who first saw one of these artworks in 1910. Although his theories regarding the heads’ origins were underpinned by entrenched, racist ideas, his fascination for Yoruba artworks began a change in how the Western world regarded African cultures.

The Sacred Grove

Born to a middle-class family in Berlin in 1873, then the capital of the new German Empire, Frobenius spent his childhood and youth reading the chronicles of 19th-century explorers, which awakened his fascination for the African continent. Starting in 1904, Frobenius traveled to Africa, returning from trips with thousands of cultural items that he sold to German museums.

In 1910 he began his fourth expedition, passing through the territory of the Yoruba, then controlled by British Nigeria. Emerging around 1,000 years ago, Yoruba culture flowered in the region, and its people founded many kingdoms and cities. Today the Yoruba still make up one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria.

Frobenius spent about three weeks in the city of Ife. Established around the 11th century, Ife was well known for the skill of its artisans. Frobenius knew of the rich culture of the wider area because in 1897 the British had taken elaborate bronzes from the palace of the Kingdom of Benin, a neighbor of the Yoruba.

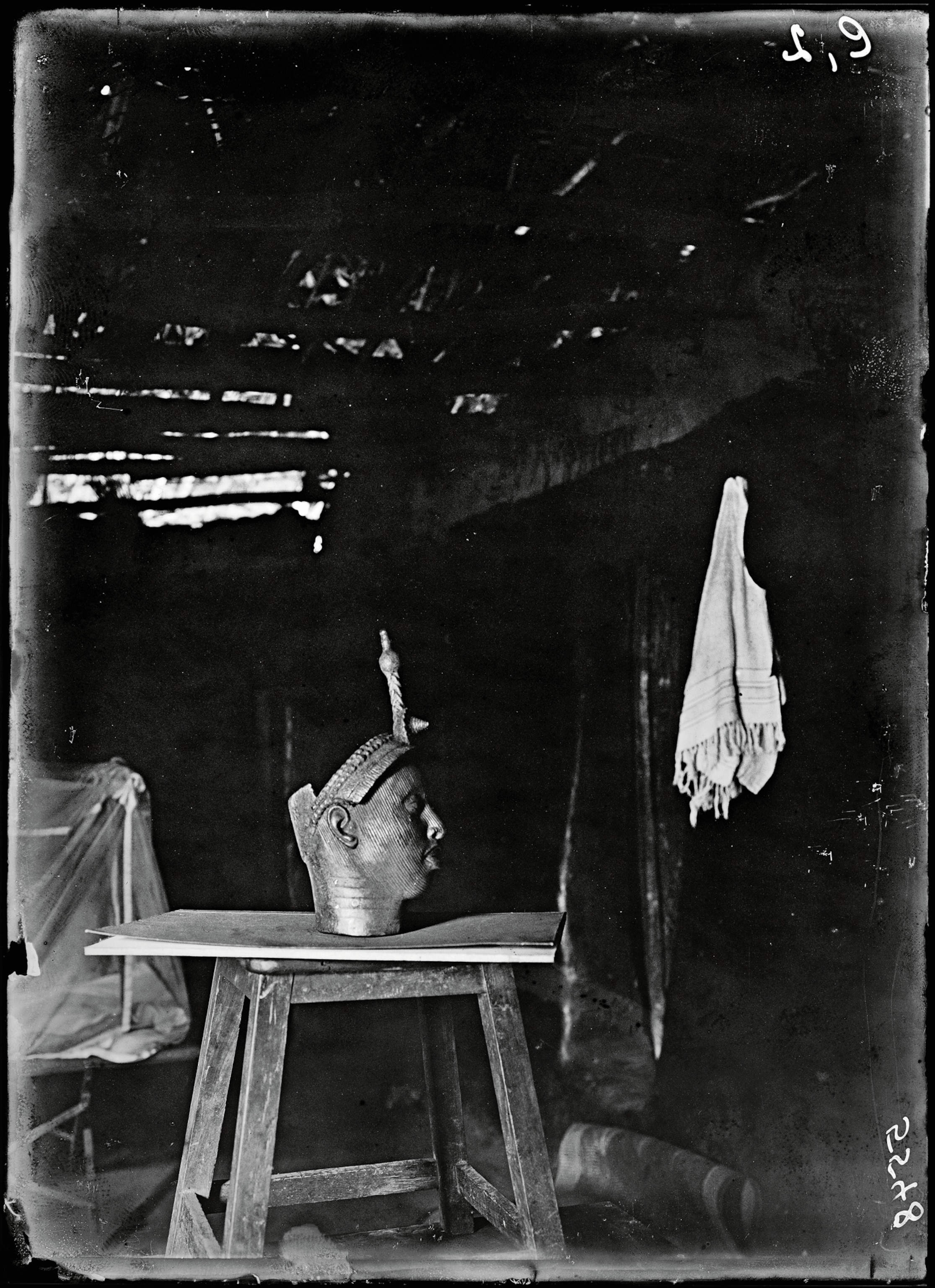

Although Frobenius’s knowledge of local culture was thin, he had learned of an artwork in Ife that he believed to be dedicated to the god Olokun, a Yoruba sea deity. He asked to see it and was escorted to a sacred palm grove, where the object lay ritually buried. His hosts unearthed it for him to inspect.

He described it as “a head of marvelous beauty, wonderfully cast in antique bronze, true to life, encrusted with a patina of glorious dark green.” Naming it the “Olokun Head,” Frobenius pressured the priest of the grove to sell it, reportedly for a price of six British pounds.

The sale caused consternation among the Yoruba elders, and the matter reached the ears of the British administration. As Germany was a rival colonial power in West Africa, Frobenius’s activities were attracting attention. He was forced to return the Olokun Head to Ife. He did, however, manage to return to Germany with several terra-cotta heads from the city.

Despite his admiration for these sculptures, Frobenius could not accept that they had been made by Africans. His racism led him to concoct a ludicrous theory that survivors from the legendary Greek island of Atlantis brought their Greek civilization to Africa, which could be seen in Yoruba art. The Yoruba god Olokun, supposedly the figure depicted by the head, was, he said, the Greek sea god Poseidon.

The Olokun Head, he wrote, had “a symmetry, a vitality, reminiscent of Greece and a proof that, once upon a time, a race, far superior in strain to the Negro, had been settled here.” These ideas were representative of European thinking in the early 20th century. Nigerian archaeologist Ekpo Eyo later wrote that preconceived notions of so-called Western civilization blinded non-African scholars to the fact that complex sophisticated works of art and culture could come from Africa:

“Those in power in Europe in previous centuries resorted to dividing humanity into two strongly divergent groups: the Western world and the non-Western one ... These issues evidently so beclouded the minds of scholars that for a long time, indeed until the late 20th century, they denied the art of Africa a proper place in the history of universal human creative endeavor.”

Revealing the Ife

Because the Olokun Head disappeared after its return, it is difficult to know with certainty its age. Scholars believe it most likely dated to around 1350.

European scholars returned to Ife in search of more bronzes. From ritual resting places, they unearthed numerous terra-cotta heads, many of which were taken to museums.

The most significant find occurred in 1938, when more than a dozen heads were found. Like the lost Olokun Head, these were made of a copper alloy but widely referred to as bronzes. Many can be seen today in Ife’s Museum of Antiquities. By 1948 archaeologists had accepted that the heads were the work of Yoruba artisans and not people from Atlantis.

The Ife heads played a key role in overturning prejudices that Africa produced only “primitive” art. Responding to a 1948 exhibition of the heads at the British Museum, a London publication declared: “This African art is worthy to rank with the finest works of Italy and Greece.”

Study has shown that the regal heads are not gods but men—the ooni, rulers of Yoruba kingdoms. Wealthy ooni obtained the metals for the artworks by trading gold and ivory along the Saharan routes to Europe. To the Yoruba, the heads are more than just beautiful objects. In Yoruba belief, the head is the home of the Ori, the seat of the soul and the place where a person’s fate is determined.

(This ivory relic reveals the colonial power dynamic between Benin and Portugal.)

Because of the deep spiritual significance of these and other objects produced in Ife, many Nigerians are advocating for the Ife heads’ repatriation, part of a wider debate as to whether African artifacts should be returned to the land that created them.