A Scientist Becomes a Photographer to Help Save Our Oceans

Doctor Enric Sala was working as a marine biologist when one day it dawned on him that he was “writing the obituary of the ocean.” He realized that his research alone wasn’t going to save the ecosystems he was so passionate about. So to the title of scientist he added a slew of new roles, including public relations expert, advocate, and photographer for his work with the Pristine Seas project.

Sala, who is now an explorer-in-residence for the National Geographic Society, initially pitched the idea of Pristine Seas to the Society in 2008. They’ve been dedicated to “exploring and protecting some of the last truly wild places in the ocean” ever since. To date, Pristine Seas has created seven marine protected areas (the most recent, Chile’s Nazca-Desventuradas Marine Park, was declared on October 5, 2015) and protected over 2.5 million square kilometers of ocean.

I spoke with Sala about his transformation from scientist to photographer, his new book on the Pristine Seas project, and why he works so hard to share his infectious love of oceans with the world.

BECKY HARLAN: You play a lot of different roles in your work with Pristine Seas. How do you balance it all?

ENRIC SALA: It’s really fun, but I feel like I live a schizophrenic life going from the suit to the wet suit. I started as a marine biologist, and then I realized that I had to do much more and learn much more about other disciplines for the science to have an impact. It was really fun to learn about communications, media production, policy, and politics. I have a great team of people who do all that, but I think it’s very important for me to know a little bit of everything that is needed to translate the science into real conservation action.

BECKY: What comes first, being a photographer or a scientist?

ENRIC: Personally, I see myself as all of these things. Most people still identify me as a scientist. One thing about publishing the Pristine Seas book is it’s a strong statement about the stupidity of putting people in silos. “You’re a scientist, so you cannot write or take photos.” “You’re a photographer, so you can’t explore.” “You’re a scientist, so you can’t know about poetry.” So it’s been really satisfying to prove all these people wrong.

BECKY: When did you take your first underwater photos?

ENRIC: I had done a bunch of expeditions in academia. I was counting fish, entering data, and working on the details side of it. I was really jealous that I didn’t have time to take photos, which I loved. So in 2009, at our Southern Line Islands expedition, I decided I was going to bring someone to do my job, to count the fish. I spent a year and a half raising funds and preparing, so since I did all the work to make it happen, I would do something that would make me very happy in the field.

BECKY: What was that first photographic experience like?

ENRIC: It was a total disaster. They were out of focus. I didn’t have a strobe. They were so bad. It took me a while to make a decent photo underwater. I learned from different ways. Just looking at David Doubilet’s books was my big inspiration, and then afterward learning from the greatest underwater photographers at National Geographic and practicing a lot, seeing what works and what doesn’t.

BECKY: One of the goals of Pristine Seas is to create marine reserves. How does photography play into that goal?

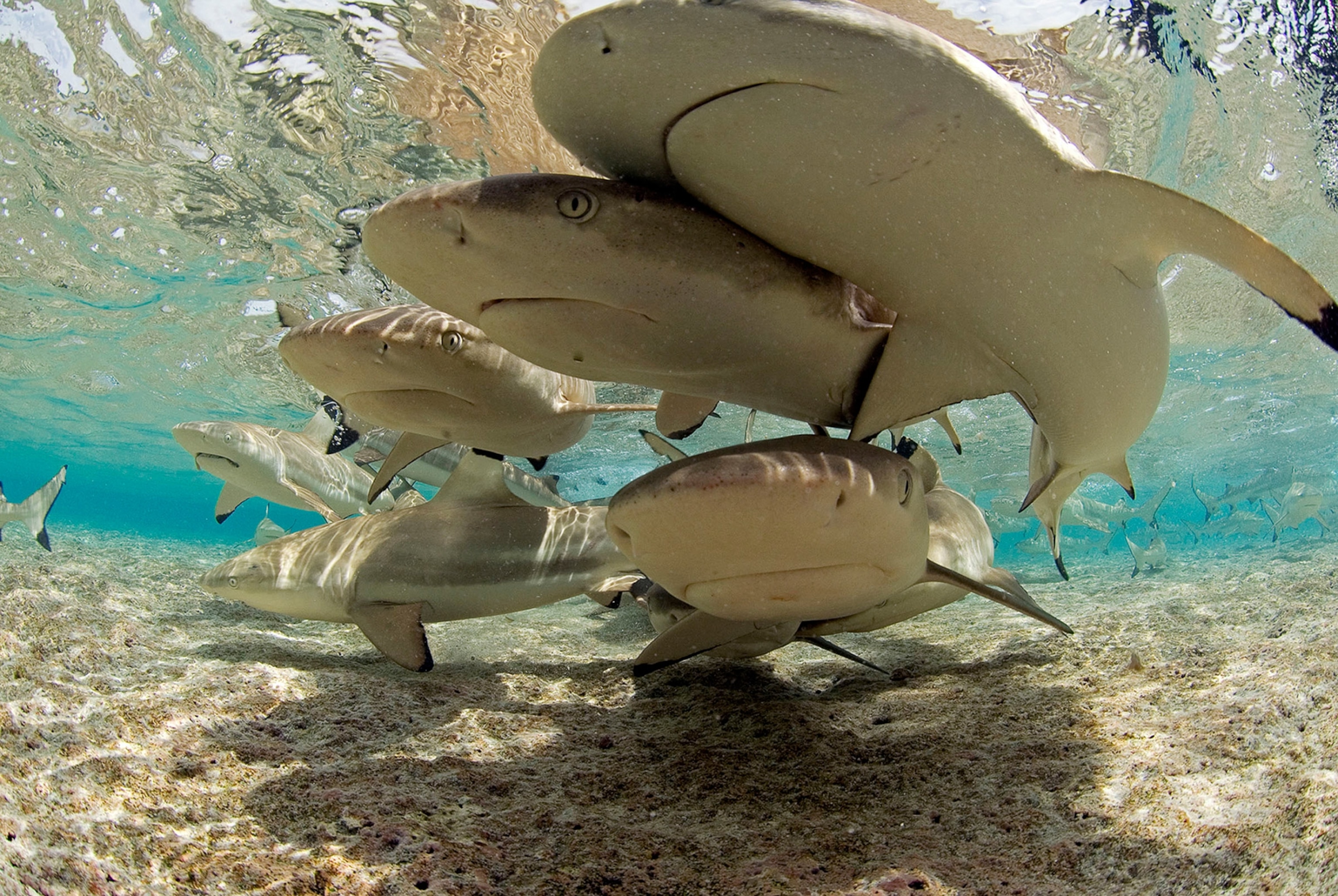

ENRIC: Photography and film play a very important role: to share what’s there with people. The science [and] the economics show these places are important from a rational perspective, but we also need to inspire the leaders and the public emotionally. We need them to fall in love with these places. Sometimes [public leaders] can join us on the expedition [for] a day or so, but sometimes they can’t come with us on remote expeditions. We bring the place to them—that’s why photography and film is important.

BECKY: What are the biggest threats to the health of the ocean?

ENRIC: There are three big issues. One is overfishing. Taking fish out of the ocean faster than they can reproduce—some [fisheries] have already collapsed. We’ve killed 90 percent of many species of sharks in the last century.

The second is pollution, especially plastic pollution. Every year, eight million tons of plastic [goes] in the ocean. If it continues like this, by 2050 there will be one ton of plastic for every three tons of fish in the ocean. And the fish end up eating the plastic we put in the ocean, so we’re polluting ourselves.

The third is climate change. It’s making the ocean warmer and more acidic, which affects species, from the smallest to the largest, throughout the entire food chain.

BECKY: Why should people care about the ocean?

ENRIC: People care about land areas because they are able to see them. The ocean suffers from the “out of sight, out of mind” problem. But protecting these large areas of the ocean helps us keep the ocean healthy and productive. The ocean gives us more than half of the oxygen in the atmosphere that we breathe. Microscopic plants and microbes in the ocean produce all of that oxygen, more than all of the forest and lands together. And they give us millions of tons of seafood every year. The ocean captures a quarter of the carbon pollution we produce every year. Coral reefs protect shorelines from storms and big waves. The oceans provide a large part of the goods and services that make life on this planet so wonderful. So if we want to have a rich life, we need to have the ocean.

Learn more about the awe-inspiring conservation work of Pristine Seas here.