The Fearless Gaze of Mary Ellen Mark: A Friend Remembered

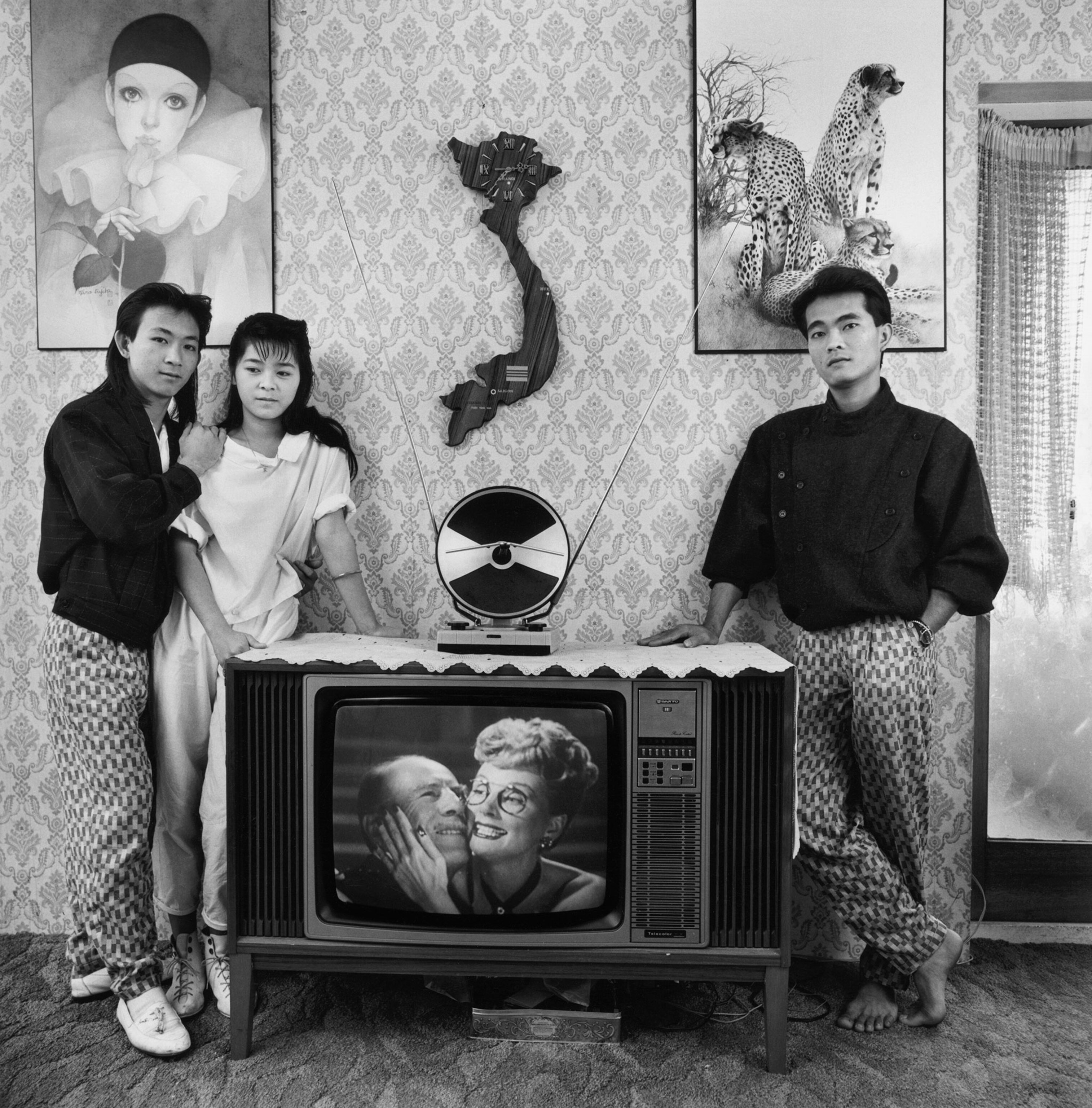

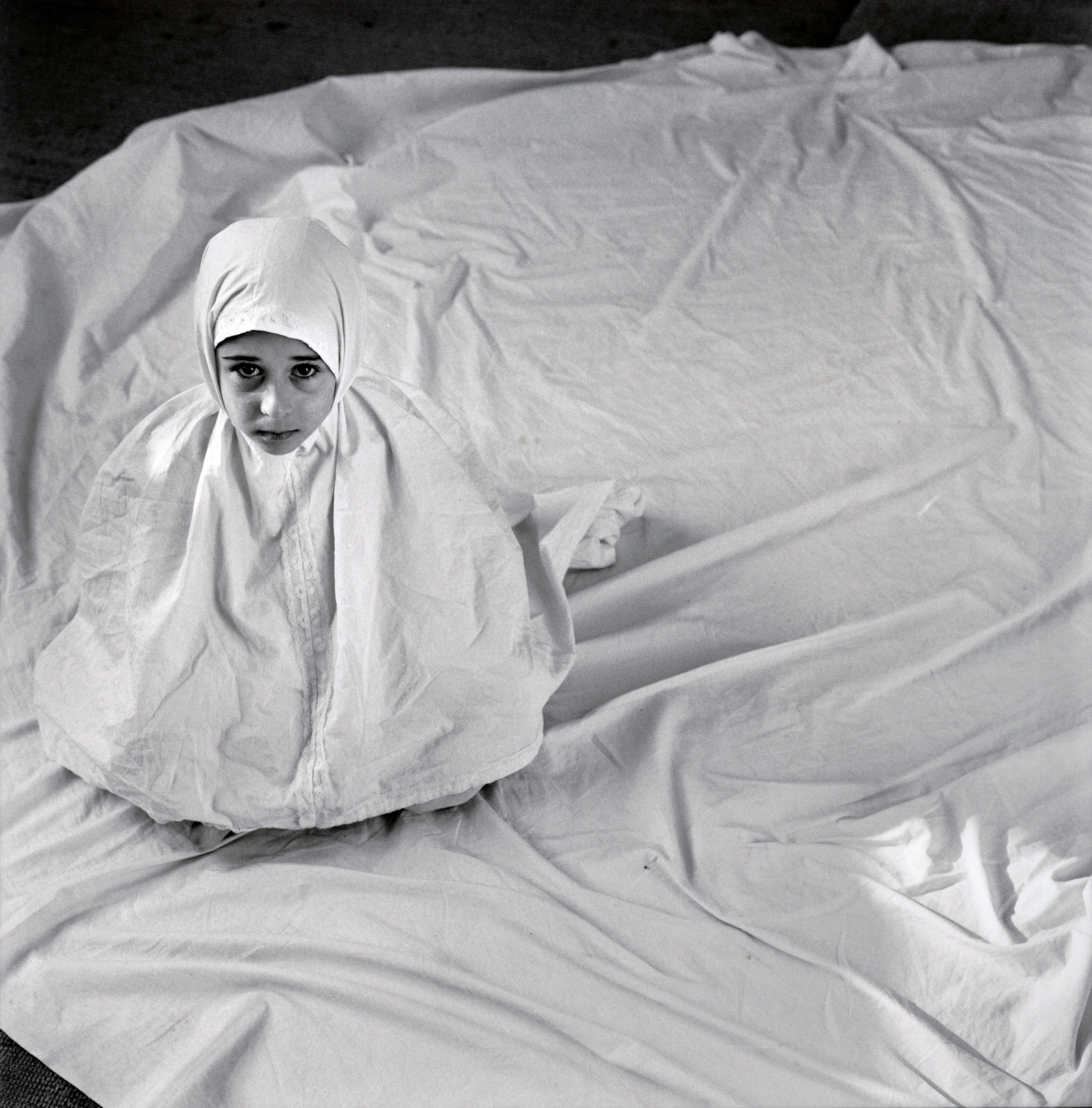

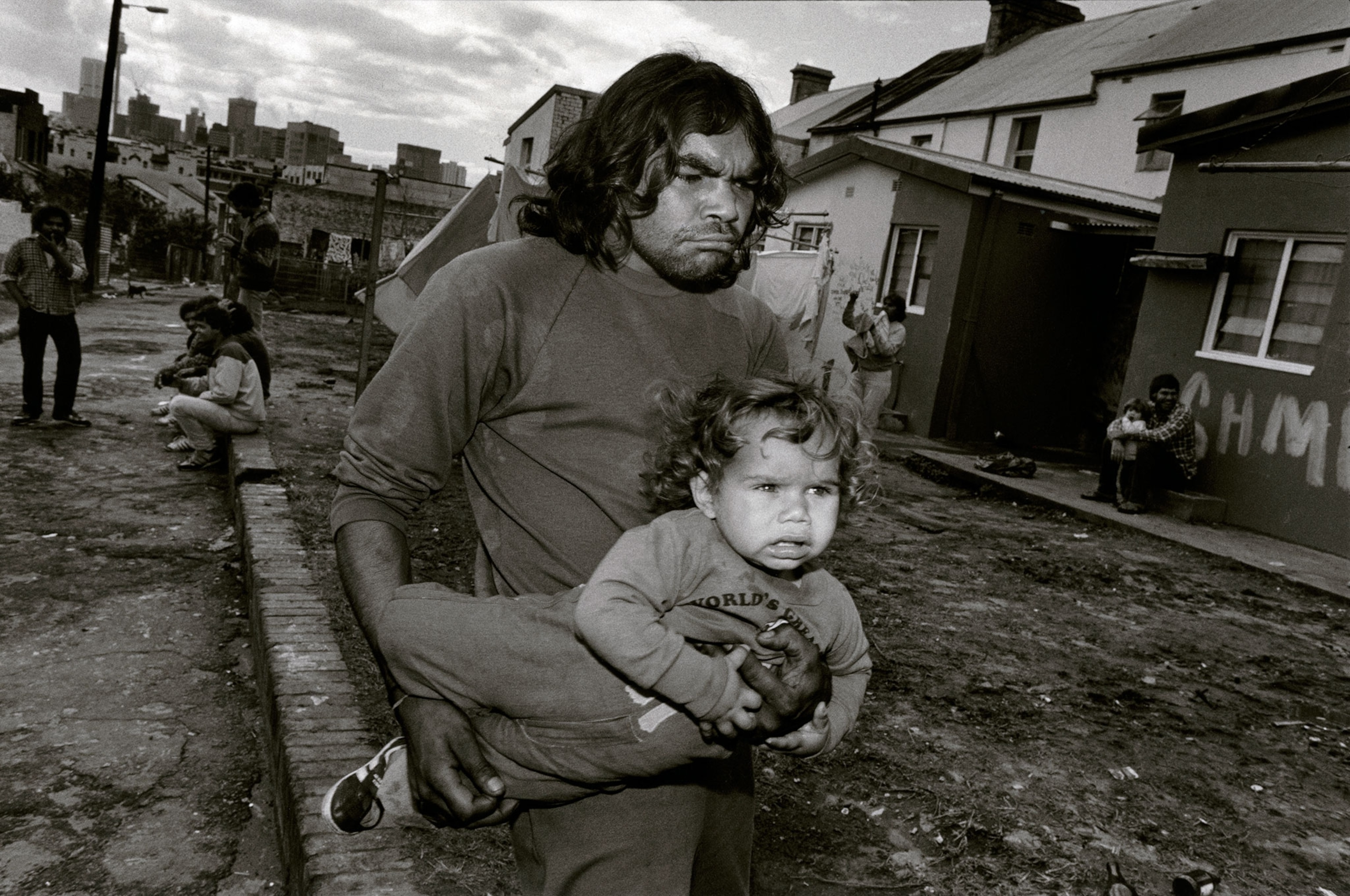

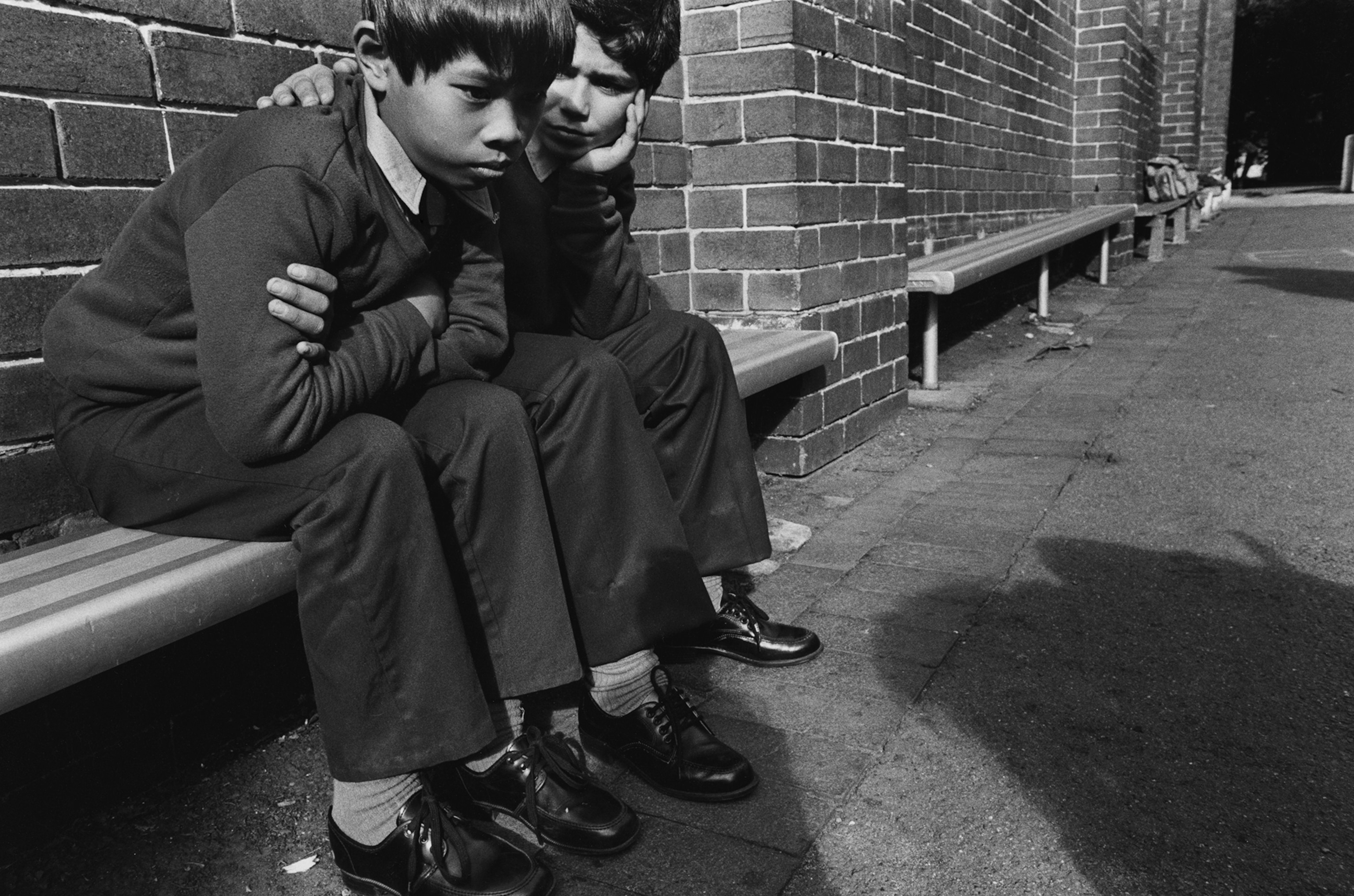

Iconic documentary photographer Mary Ellen Mark passed away on Monday, May 25. She was well known for her penetrating work and for the number of photographers’ lives she touched in a myriad of ways. In 1988 she photographed a story for National Geographic magazine in Australia entitled “Sydney’s Changing Face,” which documented Sydney’s immigrant populations. In honor of her incredible legacy, images from that story are accompanied by remembrances from National Geographic photographers, admirers, and friends.

I first saw Mary Ellen Mark’s images in the mid ’70s, when I encountered her Fulbright Fellowship photographs from Turkey in a small but delicious book called Passport. Then came her groundbreaking work on mental health in Ward 81 and her tender images of Indian prostitutes in Falkland Road. This work showed me, a young wannabe photographer, that photography was, yes, a passport to the world, but even more it was a vocation, and if practiced with passion and integrity, would allow you a meaningful life. This changed my trajectory and put me on the path that has lead me to where I am today.

What I love so much about her work is her fearless gaze. She looked at and photographed her subjects with respect, never feeling sorry for them nor pandering to them, whether they were a Marlon Brando or a homeless family living out of their car. Everyone received the same unflinching consideration. It takes courage to see the world this way and that was Mary Ellen to the core.

As a friend she was fierce, passionate, and utterly generous. She was all about loyalty. If you were fortunate enough to be in her circle she became your counselor, greatest advocate, and extremely fun and mischievous companion. Once she chose a person, like her decades-long subject Tiny in Streetwise, or a topic like circuses or blindness, or a place like India or Oaxaca, she would return again and again. This approach resulted in the incredible books and films that are so beloved to us now. She loved to work and she was always brimming with ideas, continually pushing herself and her boundaries. She never rested on her many laurels and she would never rest in peace.

Yes, she was a diva, but she earned every bit of it. Just spend some time with her work. Deep, brilliant, and everlasting.

I will miss her like crazy. Enough said. —Sarah Leen, director of photography, National Geographic magazine

Susan Welchman, Former Photo Editor, National Geographic Magazine

During my 1970s art school days I followed Mary Ellen Mark’s images. She was so far ahead. Many years later, I spent several weeks with her in Australia while producing the first of National Geographic magazine’s single topic issues. I assigned Mary Ellen to Redfern, a rough part of Sydney. She whipped everyone up to a point of frenzy before starting to shoot—I understood this fueled her unique vision. I gave her a silver hair clip my father had gotten for me, which I later saw she kept and wore.

Ed Kashi, National Geographic Photographer

When I was 18 and just learning photography, I saw Mary Ellen Mark’s book Ward 81. It was a beautiful black-and-white project about a women’s mental asylum in Oregon. It was that book that set me in motion. It was then I decided to devote my life to documentary work and photojournalism. Her work embodied the visual power, intimacy, social consciousness, and deep engagement with the world I’ve strived to achieve for the intervening 37 years.

Jodi Cobb, National Geographic Photographer

It was 1997 or 1998 and National Geographic was launching its TV channel in India. I was among the representatives sent to Mumbai to publicize the launch. Even though I’d never been there, for some reason I was tasked with leading our little group on a shopping expedition. So I went to the best for help: I called Mary Ellen Mark in New York. She wasn’t in, but 30 minutes later a fax from her arrived: Stall 47 in the Mumbai Silver Bazaar.

It turned out to be a tiny hole-in-the-wall filled with dusty old worthless knickknacks, and I was shocked. But I started to chat with the shopkeeper, told him Mary Ellen Mark had sent us, and his face lit up. New York photographer! He reached behind the counter, pulled out a glorious trove of antique gold and silver necklaces, bracelets, pendants, and earrings, threw them on a scale and charged us only by the weight.

Many others will write about Mary Ellen’s talent, drive, warmth, and uncompromising standards, her exquisite photographs and genius for storytelling, but there was always more to Mary Ellen. She liked the physical manifestations of a culture—a bracelet, textile, Mao button—along with the human. Both had stories to tell. And with both, she knew how to look beyond the dust, the clutter, and the crowd to discover those hidden treasures.

William Albert Allard, National Geographic Photographer

I can’t do any kind of justice to what Mary Ellen meant in our world of documentary photography. Who really can? She was brilliant, persistent, and prolific almost beyond belief. I often wondered how she could be in so many different places, teach so many, so well, and continue to take on major project after major project. She was like a heroine to me. We had a kind of mutual admiration society but probably met face-to-face no more than a half dozen times at best over half a century. She said things in public about my work that I’d like to think are true but wouldn’t dare proclaim myself. I will miss not having had the chance to see her more often, know her better. When she got up to leave the Annenberg Theater recently, where we were for some tech testing before our presentations, we kissed on the lips. I didn’t realize then it was goodbye.

Stephanie Sinclair, National Geographic Photographer

To me, Mary Ellen is like the grandmother of the concerned photographers. I doubt she’d like to be called that, but it’s a term of the highest endearment. The intimacy and emotion in her work is simply unrivaled—I mean, even people we’d consider master photographers in the genre have looked to her for guidance and inspiration over the years. Yet, despite this uber-legend status, she was never above taking the time to educate and encourage students and professionals alike. What more could you ask for in a matriarch?

I had the pleasure of witnessing this firsthand only a couple weeks ago in Mexico. Mary Ellen and I were both in town for a photography and film festival at a local university. I was thrilled to see her again after several years, and sure enough, there she was as always, long hair perfectly combed and braided, having traveled a long way to share her work and wisdom with students and fans. I was lucky enough to be able to give her a big hug before she traveled back home. We blew kisses to each other as her car pulled out of the hotel parking lot, rounded the corner and disappeared. This is my last memory of Mary Ellen and something I will forever cherish. And I am grateful that her giant heart and spirit will forever continue to speak to us through her photographs.

See more of Mary Ellen Mark’s work on her website.