2,000 years of shipwrecks discovered on treacherous ancient sea route

An 8-country UNESCO expedition reveals surprising finds in waters mariners were once believed to have avoided "at all costs."

The Mediterranean Sea beckons tourists with calm waters and gentle breezes, but ancient mariners knew that violent storms could arise in minutes—and archaeologists once assumed that was one of the reasons their ships would stick to coastlines. Sailors would navigate by sight from terrestrial landmarks, they proposed, rather than trying to cross the often-dangerous open seas between Europe, North Africa, and the Near East.

But discoveries from a multi-year mission by the United Nations cultural agency UNESCO have thrown new doubt on the idea that ancient sailors solely relied on coastal navigation, with an analysis that suggests sailing beyond sight of land was routine in ancient times.

The locations of a newly found ancient wreck and several others now confirm that early merchants often dared the open seas to make a profit from their cargoes of wine and olive oil. And the mission shows the value of bringing modern underwater archaeologists from different countries to work together, says UNESCO underwater archaeologist Alison Faynot, who helped coordinate the mission.

Sailing the open seas

For the latest expedition, underwater archaeologists from eight countries—Algeria, Croatia, Egypt, France, Italy, Morocco, Spain and Tunisia—explored the Sicilian Channel on board the research ship Alfred Merlin, which is operated by the Department of Underwater and Submarine Archaeological Research (DRASSM) of the French Ministry of Culture.

Their survey area included the treacherous and shallow Skerki Banks off Tunisia and deeper waters to the north and east that separate Sicily from North Africa. Together they form the shortest sailing route—90 miles—between Italy and Africa, and the region is full of marine life that’s attracted fishermen for thousands of years.

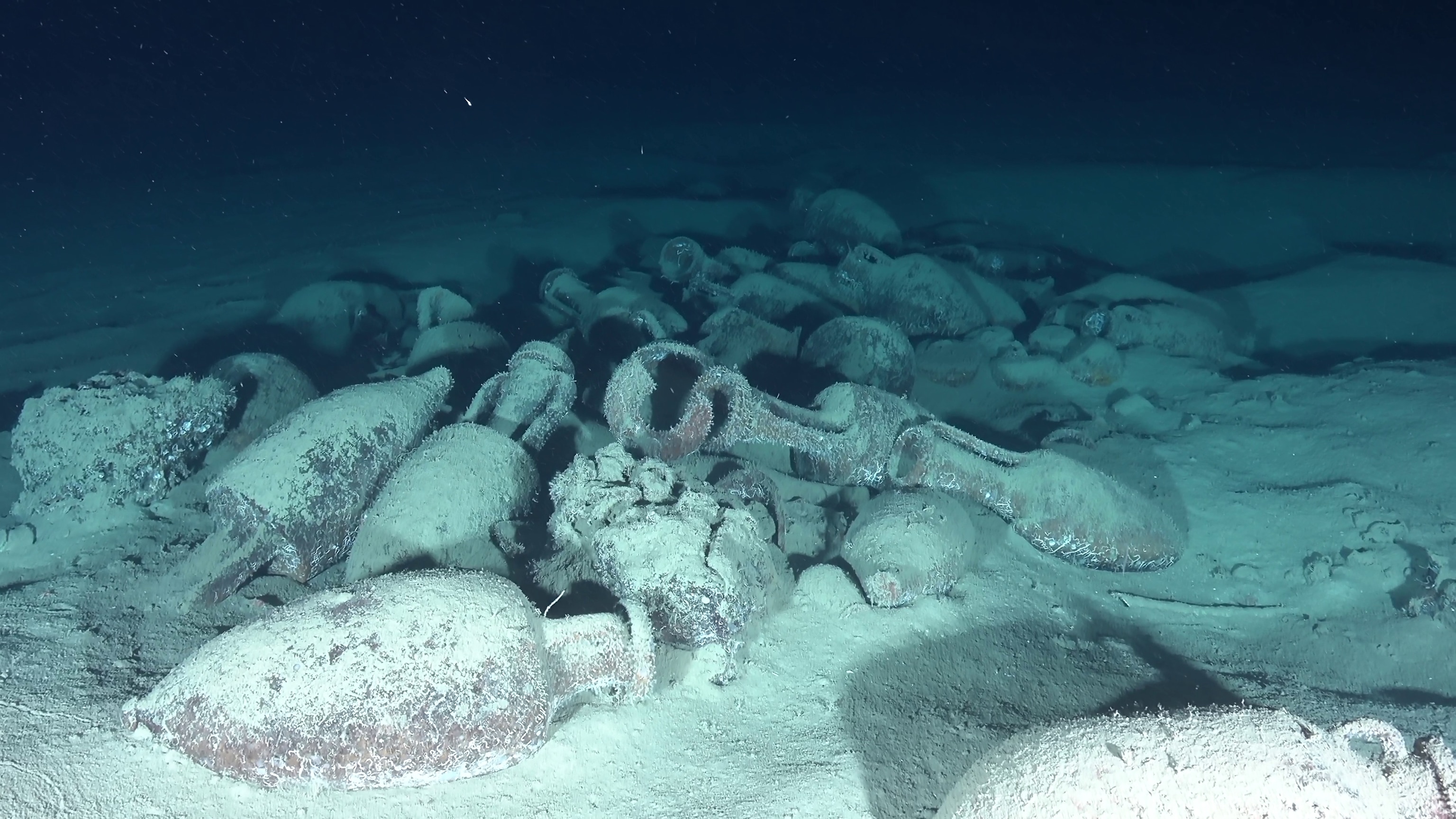

Among the new discoveries are three shipwrecks near the Skerki Banks, including a Roman merchant ship that sank more than 2,000 years ago. Underwater archaeologist Franca Cibecchini of DRASSM says the 60-foot-long ship, partially intact in 180 feet of water, was carrying amphoras when it sank. The design of the clay jars suggests they once held wine from Italy; archaeologists will now recover some of the amphoras to test that hypothesis.

The researchers also used one of Alfred Merlin’s two underwater robots, or ROVs—remotely-operated vehicles—to explore and verify the locations of three other Roman-era shipwrecks on the eastern side of the Sicilian Channel. These ships also carried cargoes of amphoras, which now lie scattered on the seafloor.

Cibecchini says the wreck locations show clearly that merchants by this time were willing to sail straight between Italy and North Africa, rather than taking a safer route that hugged the coastline.

This mirrors shipwreck discoveries elsewhere in the Mediterranean, she says, adding that technologies like ROVs and self-guided AUVs—autonomous underwater vehicles—now mean archaeologists are no longer exploring shipwrecks only in the shallow waters they were once restricted to. “In the past, most underwater archaeologists could only scuba dive, or look at artifacts brought up by fishing nets,” says Cibecchini.

Taken together, the new and old wrecks show conclusively that early merchant ships often left the coasts and crossed the open sea when there was a profit to be made—a finding that will give scholars a greater understanding of how ancient economies worked.

Dozens of shipwrecks

The Skerki Banks are almost unexplored, and the archaeologists worried there might be little to find—instead, they identified 24 new shipwrecks, ranging in dates from antiquity to modern times, among the hundreds that litter the seafloor.

The western part of the Skerki Banks is filled with rocks, often hidden by breakers and heavy swells, and parts of the seafloor are dangerously shallow. Several dangerous reefs lie just below its surface, including one near the center of the Sicilian Channel that’s two miles long. Trawling nets from fishing operations regularly scoop up artifacts along with marine life from deep along the seafloor.

“We knew this was a very dangerous area, and we knew also that there had been a lot of looting,” says UNESCO’s Faynot. “We were afraid of finding a deserted area—but we were happy to find shipwrecks instead.”

One relatively recent wreck, a 250-foot-long metal ship, may date from the late 19th or early 20th centuries. But no cargo can be seen nearby and it does not appear to be a warship, she says. Further research with historical documents could help identify it.

Deep-sea discoveries

University of Malta maritime archaeologist Timmy Gambin, who wasn’t involved in the expedition, says the Skerki Banks area was heavily sailed in ancient times, despite the dangers: “The area… would have been something an ancient mariner needed to navigate but wanted to avoid at all costs.”

And he adds that deep-sea technologies, like the ROVs on the Alfred Merlin, have transformed underwater archaeology.

“In the not-so-distant past, deep water technologies were not widely available and deepwater projects were the realm of the few,” he says. But “we can now do archaeology systematically at depth… [and] the science can now be initiated and conducted by local experts.”

And there is much more to discover in this region. The latest expedition looked only at wrecks along the north and south navigation between Sicily and Tunisia.

But there is also an east and west navigation that has yet to be explored, which once linked the ancient riches of the eastern Mediterranean to younger nations in the west; and UNESCO’s ability to link underwater archaeologists from different countries will aid such investigations, Faynot says.

Wrecks from other times, as well, could help fill in the sunken history of the region: “I would be very hopeful that one day we might find, for instance, a medieval shipwreck,” she says.