The story of Turtle, one of the world's first submersibles

A vehicle that could dive underwater … and stay there? During the Revolutionary War, an American colonist built an experimental submersible vehicle that George Washington called “an effort of genius.”

Submersibles are associated with today’s most modern scientific—and touristic—endeavors. But the idea is much older than you might think. In fact, one of the earliest submersibles dates to the 18th century and the American Revolutionary War.

The Continental Army was scrappy and determined, often reliant on guerrilla tactics against the more traditional British army. Both sides made inventions of necessity during the war: Invisible ink allowed American spies to bypass British censors without raising suspicion, while the breech-loaded rifle enabled the British to experiment with more efficient arms.

But no one seems to have seen submarine warfare coming—except the rebellious colonists.

(Bob Ballard and James Cameron on what we can learn from the Titan tragedy.)

Bushnell invents the Turtle

While studying at what is now Yale University in 1775, a farmer’s son named David Bushnell watched the progress of the revolt’s early days and imagined what warfare would be like if it were possible to conduct it underwater. Bushnell had a restless mind and had tinkered with a variety of inventions to help the colonists’ cause.

Bushnell believed that naval warfare would be key to the Revolution—after all, the British Crown imported its legions of redcoats by ship and was already using its naval prowess to blockade the unruly colonists and force them to surrender. But Bushnell wanted to fight British ships in a new way: from beneath the water. To that end, he began constructing an experimental craft that could dive beneath the water and stay there, allowing its operator to bomb other watercraft with a timed explosive.

(How the Declaration of Independence wooed Americans away from Britain.)

It is unclear how much of Bushnell’s idea was unique and how much was derived from earlier European innovations in naval warfare. Bushnell likely drew on accounts of Dutch inventors like Cornelis Drebbel, who had created the first functional submarine in 1620. What is clear is that Bushnell eventually got in touch with other revolutionary sympathizers, including local clockmaker Isaac Doolittle, who made some of the precision instruments needed for his new machine.

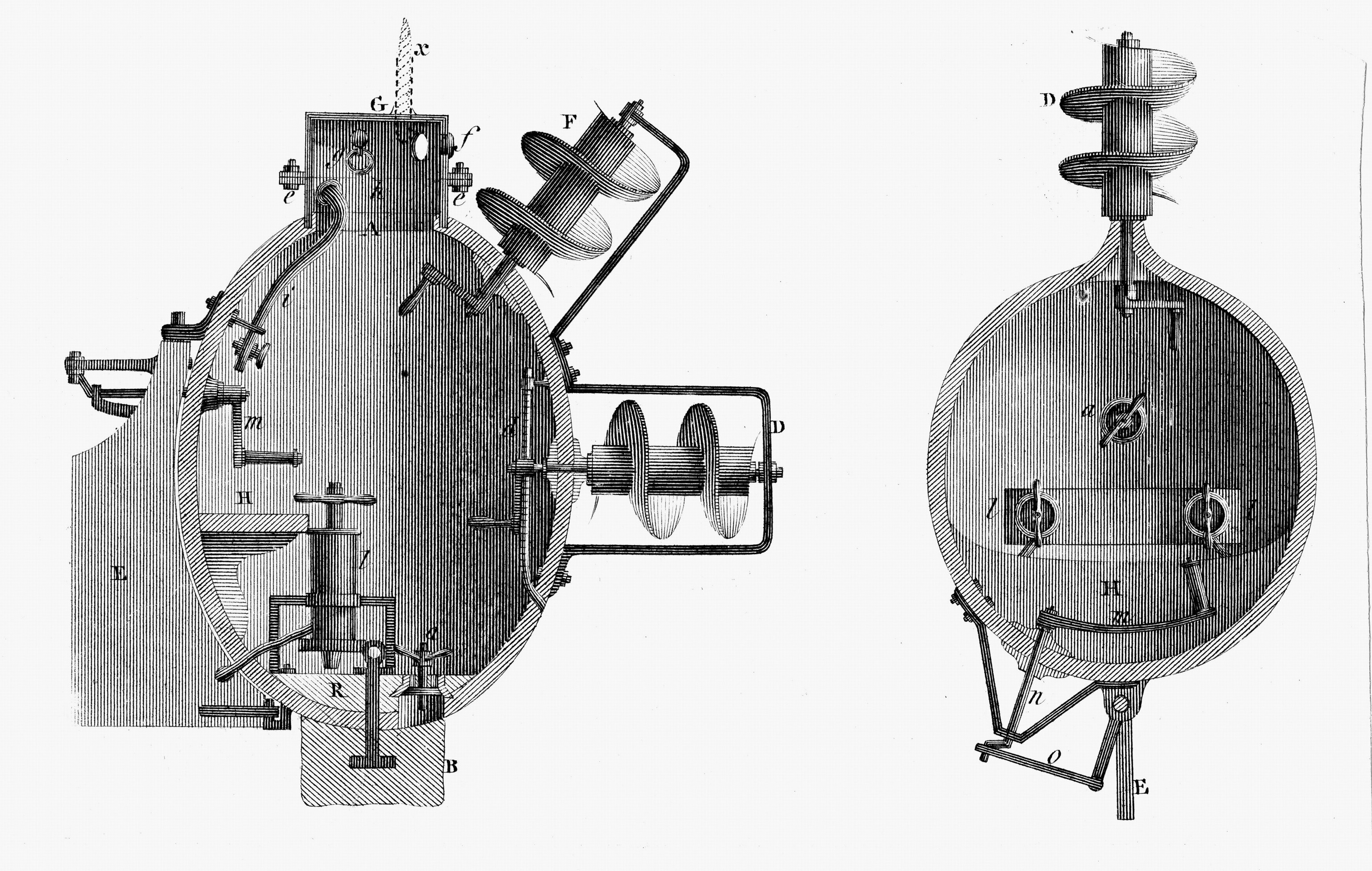

And what a machine it was: Bushnell envisioned a barrel-like vessel that would fit one operator, enclosing him in two shell-like halves that earned the device its name, the Turtle. Inside the oak-hulled orb, the operator would use ballast and a pump to flood the lower portion of the vessels with water to make it submerge.

The operator would then have about 30 minutes’ worth of oxygen to breathe while propelling the craft toward its target with a pair of hand- and foot-powered propellers and a rudder, using light from windows to navigate. Once having reached an enemy ship, the operator could use a primitive drill-like attachment on the hull of the Turtle to bore a hole in the target, fill it with a timed weapon, and speed away undetected before it exploded.

Bushnell’s Turtle goes to war

Bushnell’s Turtle soon gained some impressive supporters, including technology-obsessed Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Gale, a physician and pamphleteer with connections to the Revolution. Even George Washington had heard of Bushnell’s machine. In a 1785 letter, Washington wrote that the Turtle was “an effort of genius”—but noted that Bushnell’s inventions always seemed to be plagued by accidents.

(The blast that marked the beginning of the American Revolution.)

And when Bushnell’s invention made its big debut in September 1776, the misfortune Washington had described as one of the inventor’s trademarks made itself known. Bushnell’s brother, Ezra, had been the device’s planned first operator, but fell ill on the night of the mission and was unable to participate.

Instead, Sergeant Ezra Lee carefully maneuvered the Turtle and a magazine of gunpowder toward Britain’s 64-gun H.M.S. Eagle in New York harbor by night on September 6. But Lee hit metal instead of wood and so he was unable to drill into the ship, forcing him to abandon the target and propel the Turtle back landward.

The Turtle had failed, but Bushnell’s timed explosive which he left behind didn’t.

“In less than half an hour a terrible explosion from the magazine took place, and threw into the air a prodigious column of water, resembling a great water-spout, attended with a report like thunder,” wrote American surgeon James Thacher in his military journal. “[American] General Putnam and others, who waited with great anxiety for the result, were exceedingly amused with the astonishment and alarm which this secret explosion occasioned on board of the ship.”

The fate of the Turtle

Though the Turtle attempted a few more missions, a variety of issues from tides to operator error always thwarted its efforts. Ultimately, in October 1776, the Turtle itself was sunk along with the ship that was transporting it. Historians believe the colonists were able to recover it, but its eventual fate is unknown.

Either way, Bushnell had opened American minds to the possibility of underwater warfare, and set the stage for the torpedo, the timed mine, and the use of propeller-driven craft and submersibles. As historian Alex Roland writes, the story of the Turtle endured “based on war stories and eulogies originally intended to serve the purposes of scientific nationalism, patriotic pride, and the human taste for a good yarn.”

As for Bushnell, his explosive innovations did see use in the war. But he’ll always be best known for the Turtle, the early submersible now lost to the passage of time and the tides of technology.