DNA Reveals Far-Off Origins of Ancient 'Gladiators'

DNA testing is telling scientists more about the origins of a group of headless Romans.

People in the Roman Empire really got around.

Evidence from a Roman-era cemetery in York, England shows that the city—once a major outpost on Rome’s distant frontier—was home to both locals and to immigrants from thousands of miles away.

In a paper published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, Trinity College Dublin geneticist Dan Bradley and his colleagues analyze DNA preserved in the dense inner ear bones of seven skulls found in the cemetery. They report that six of the skeletons have DNA matching people living in modern-day Wales. But to researchers’ surprise, one of the men came from a long way away—the other end of the Roman Empire, in fact.

“The nearest genetic matches were from Palestine or Saudi Arabia,” Bradley says. “He definitely didn’t come from Europe.”

To confirm the DNA results, Gundula Müldner of the University of Reading analyzed chemical signatures in the skeleton's teeth for clues. The differences between this sample and the others were dramatic.

“This Near Eastern chap really, really stands out. He was from somewhere arid and hot,” she says. “Where he fits best is the Nile Valley or an environment like that—we can’t pinpoint it exactly, but somewhere in the Near East.”

Inscriptions, literary sources, and other evidence have suggested the Roman Empire’s elite often immigrated from one part of the empire to another. There’s even a Roman burial from York that contained a woman from Africa wearing an ivory bracelet.

Bradley's research adds new understanding to what was already an intriguing find. The skeletons that were tested were among many discovered in 2004. The cemetery they were buried in was once on the outskirts of Eboracum, a Roman legionary fortress and settlement that was one of the largest in Britain 1800 years ago. “York was a major town—emperors stayed there when they visited Roman Britain,” says Hella Eckhardt, an archaeologist at the University of Reading in the UK who specializes in Roman-era Britain and was not involved with the study. “There was a major military presence there, too.”

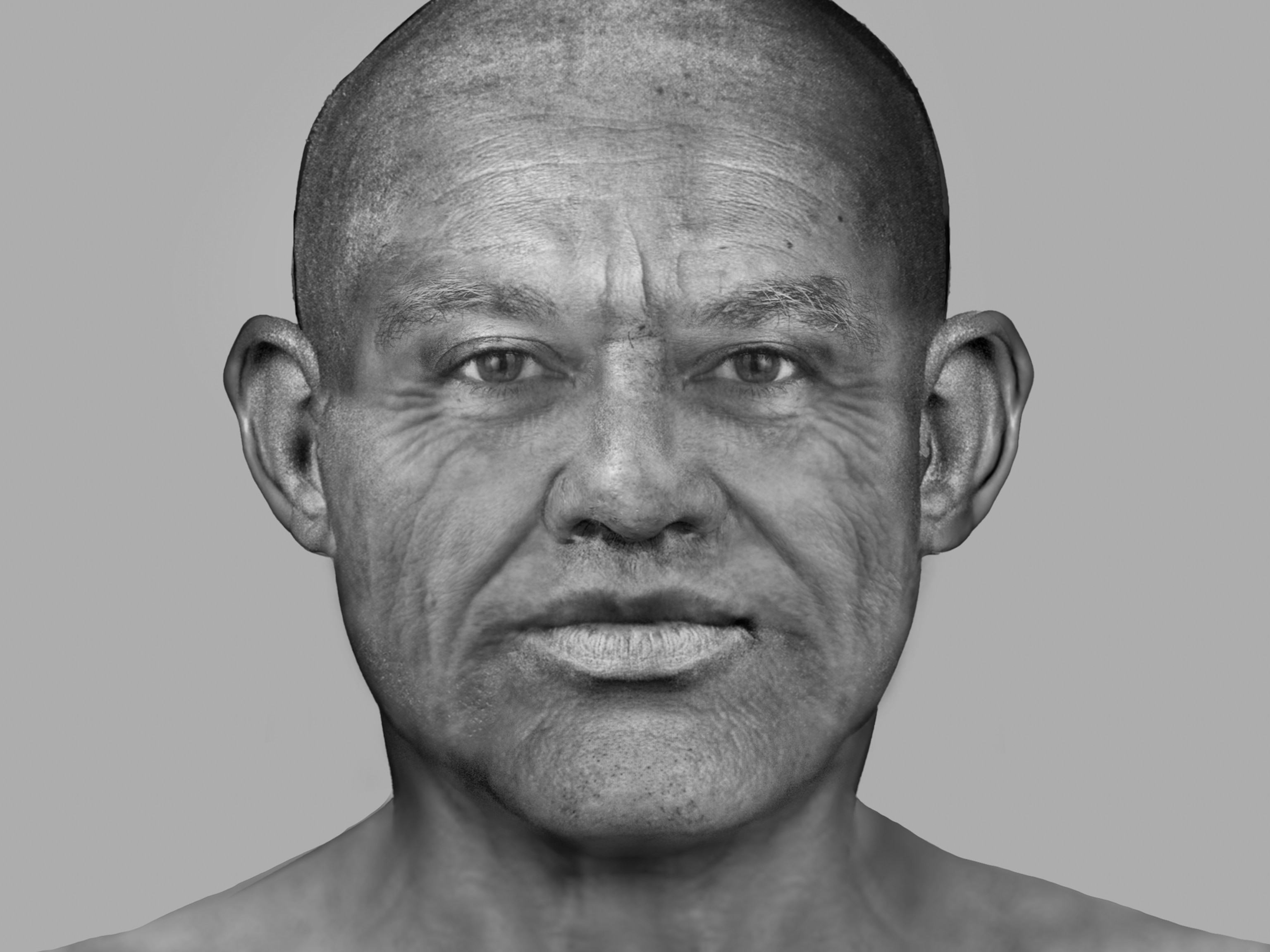

The men—archaeologists found 80 in all—were no strangers to violence. Many of the skeletons showed signs of healed injuries. One had even been bitten by a large predator, perhaps a lion or bear. Strangest of all, about half were decapitated at or just after death and buried with their detached heads.

Based on their skeletons, archaeologists could tell all of them were under 45, taller than average and well-muscled. “One explanation,” Bradley says, “is that they were gladiators or Roman soldiers.”

Previous analysis of chemical signatures in the bones and teeth of other skeletons from the cemetery had determined that some of the men grew up in colder climates, perhaps Germany or further east in continental Europe. The chemical evidence also indicated some of them ate millet grain—a crop that was unavailable in Britain—as children.

Experts say the latest findings may be the first DNA evidence of the Roman Empire’s cosmopolitan character. Further research could help scholars understand how non-elite Romans lived and traveled.

“This shows there is mobility, especially in urban and military contexts,” Eckhardt says. “With this DNA, we’re able to take a much broader sample and find out where they’re coming from.”