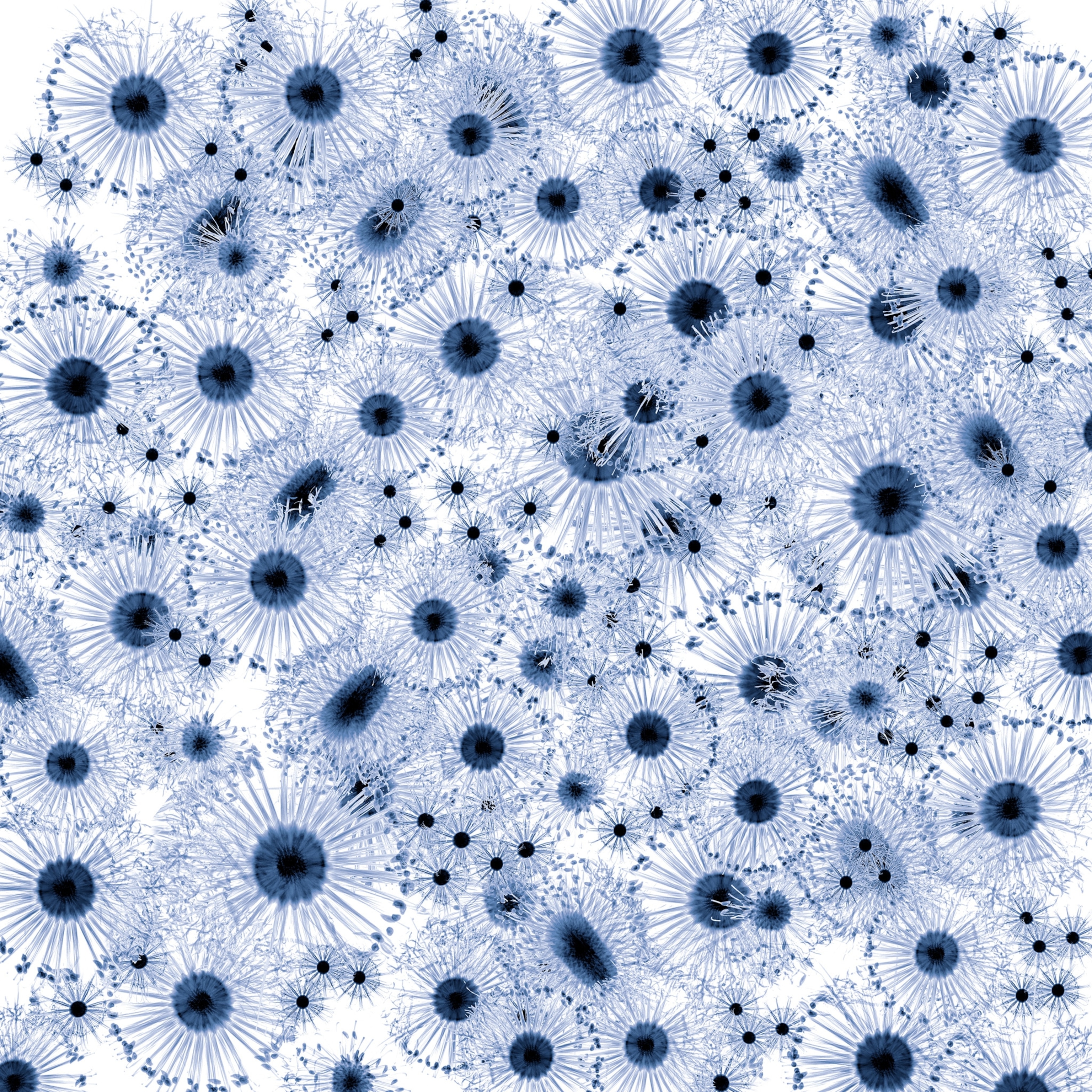

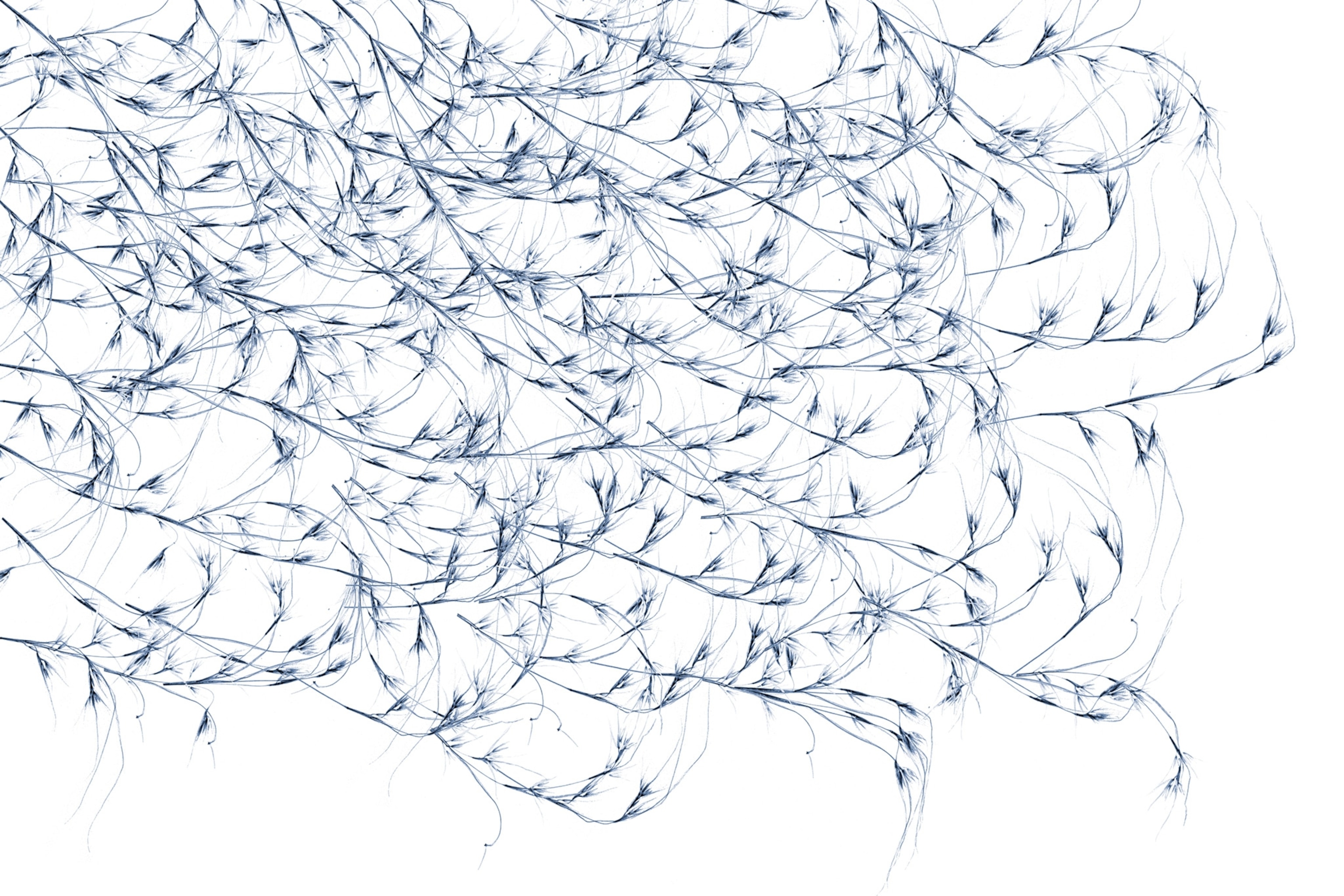

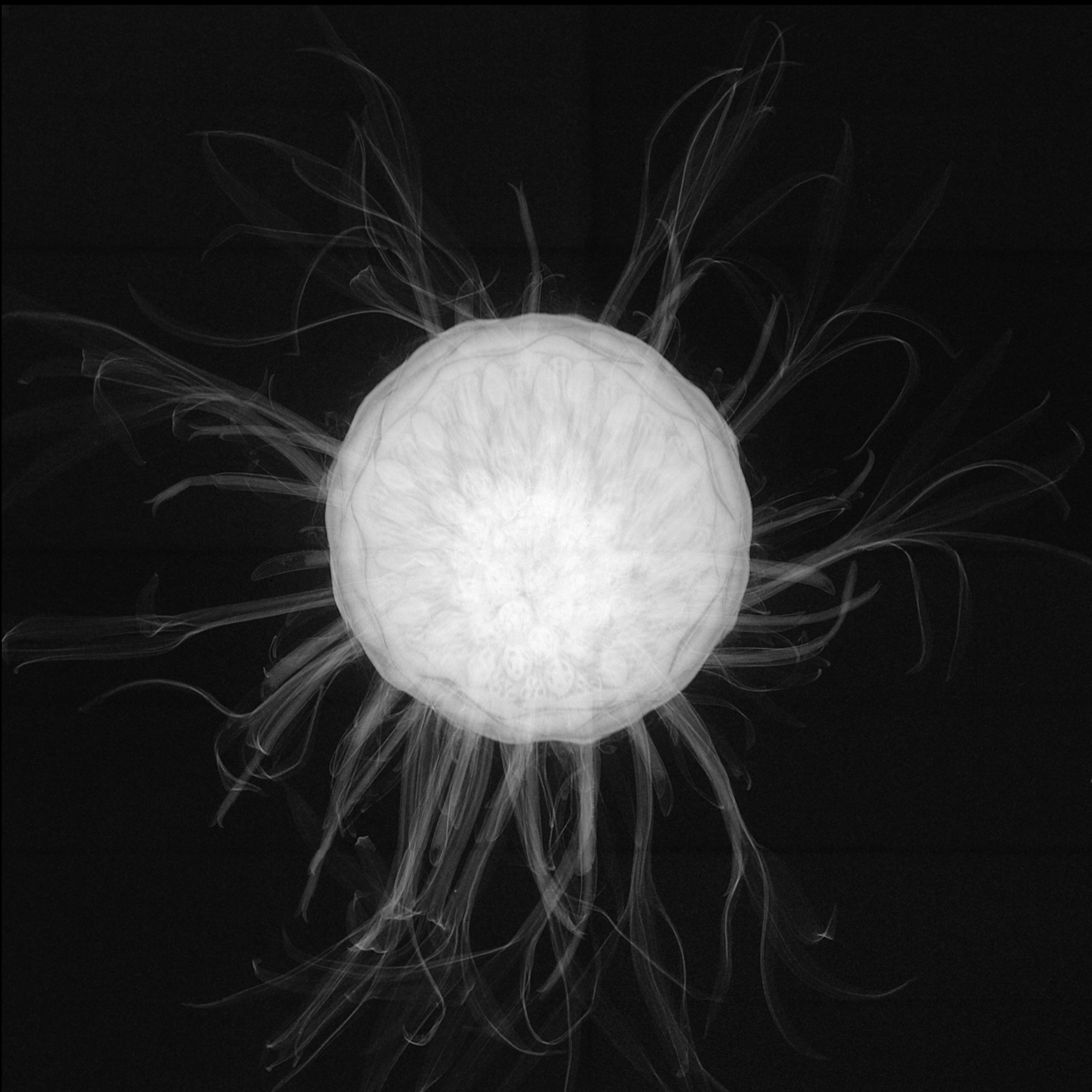

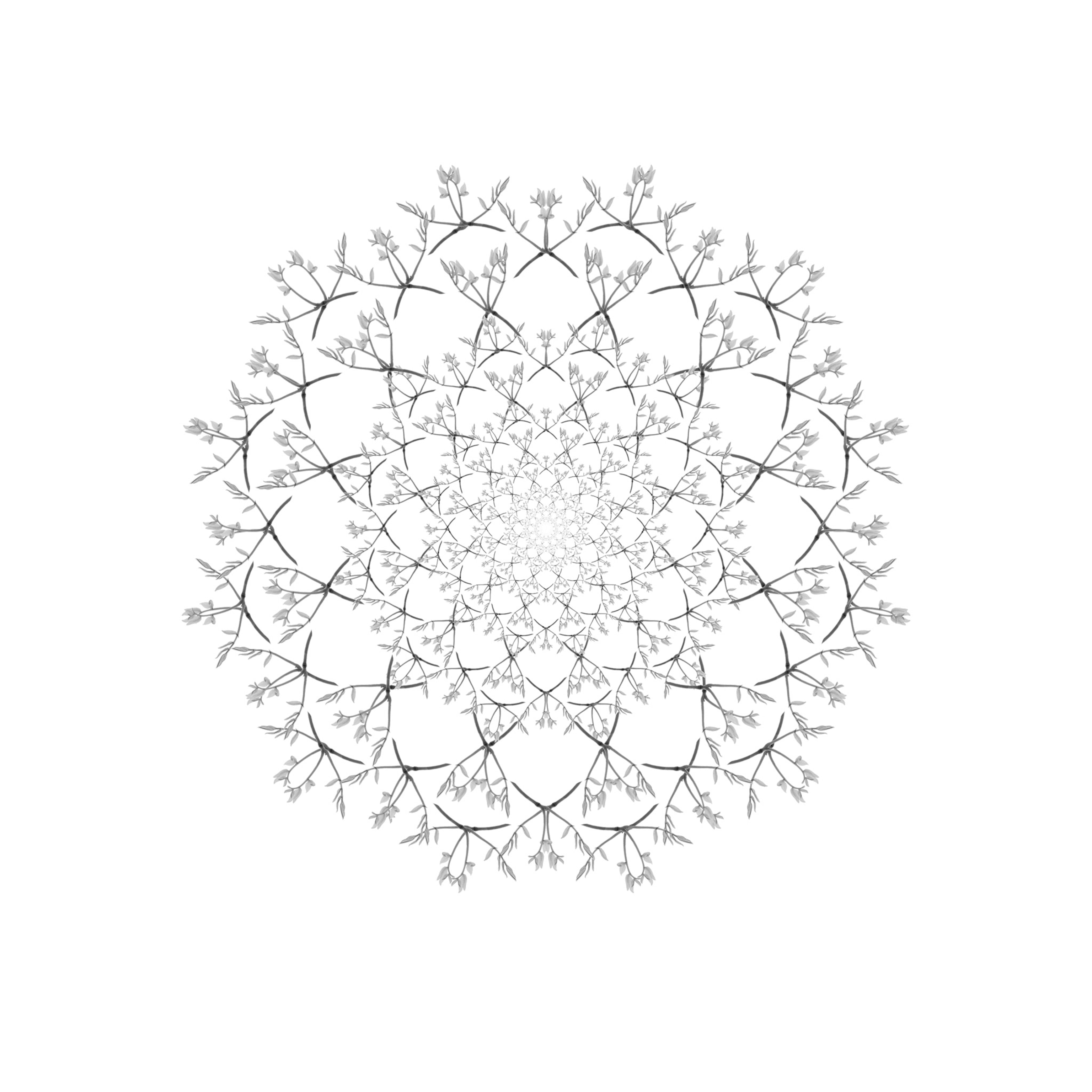

No bigger than a speck of dust, an orchid seed seems like a fragile thing. Yet, under the right conditions, this tiny grain—among the smallest from any flowering plant—can survive in the wild for years, eventually germinating and producing one of botany’s most exquisite blooms.

Photographer Dornith Doherty has spent 10 years capturing the beauty of thousands of seed varieties for a project that she calls Archiving Eden. But orchids, she says, are special.

“They’re delicate and vulnerable, yet they have this power of life,” she says. “I find them magical.”

Doherty began researching her project after a magazine article about a seed bank in Svalbard, Norway, sparked her curiosity. The story highlighted the importance of stockpiling seeds should climate change, famine, political strife, or other events damage the food supply. Long interested in the relationship humans have with the natural world and stewarding the land, the topic of seed banks intrigued her.

“For me,” she says, “this was a very compelling idea, that somebody had built a Noah’s Ark on the North Pole—but in an effort to preserve plant life on Earth and through that, possibly the human race itself.”

Born and raised in Houston, Doherty is a research professor at the University of North Texas, where she teaches photography. In her free time—and on her own dime—she pursued the idea of a photo series on not just Svalbard, but also other seed banks. Doherty gradually received invitations to photograph collections inside vaults in the United States and England, and, after two years, Svalbard, Norway. Trips to seed banks in Russia, Australia, Brazil, and the Netherlands followed.

Seed banks serve several purposes. They stockpile reserves of countless seeds from all over the world to help ensure food security, preserve diversity in the plant kingdom, and guard against species extinction. At the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which has the capacity to store up to 2.5 billion seeds, samples are kept at a chilly minus 0.4 degrees Fahrenheit. Seeds are wrapped inside special foil packets and placed inside boxes that line the shelves within the vault.

“The low temperature and moisture level ensures low metabolic activity, keeping the seeds viable for decades, centuries, or in some cases thousands of years,” the project’s website proclaims. And since the Svalbard vault extends deep within a mountain, “the permafrost ensures the continued viability of the seeds if the electricity supply should fail.” (See what happens when a polar bear finds a camera on Svalbard.)

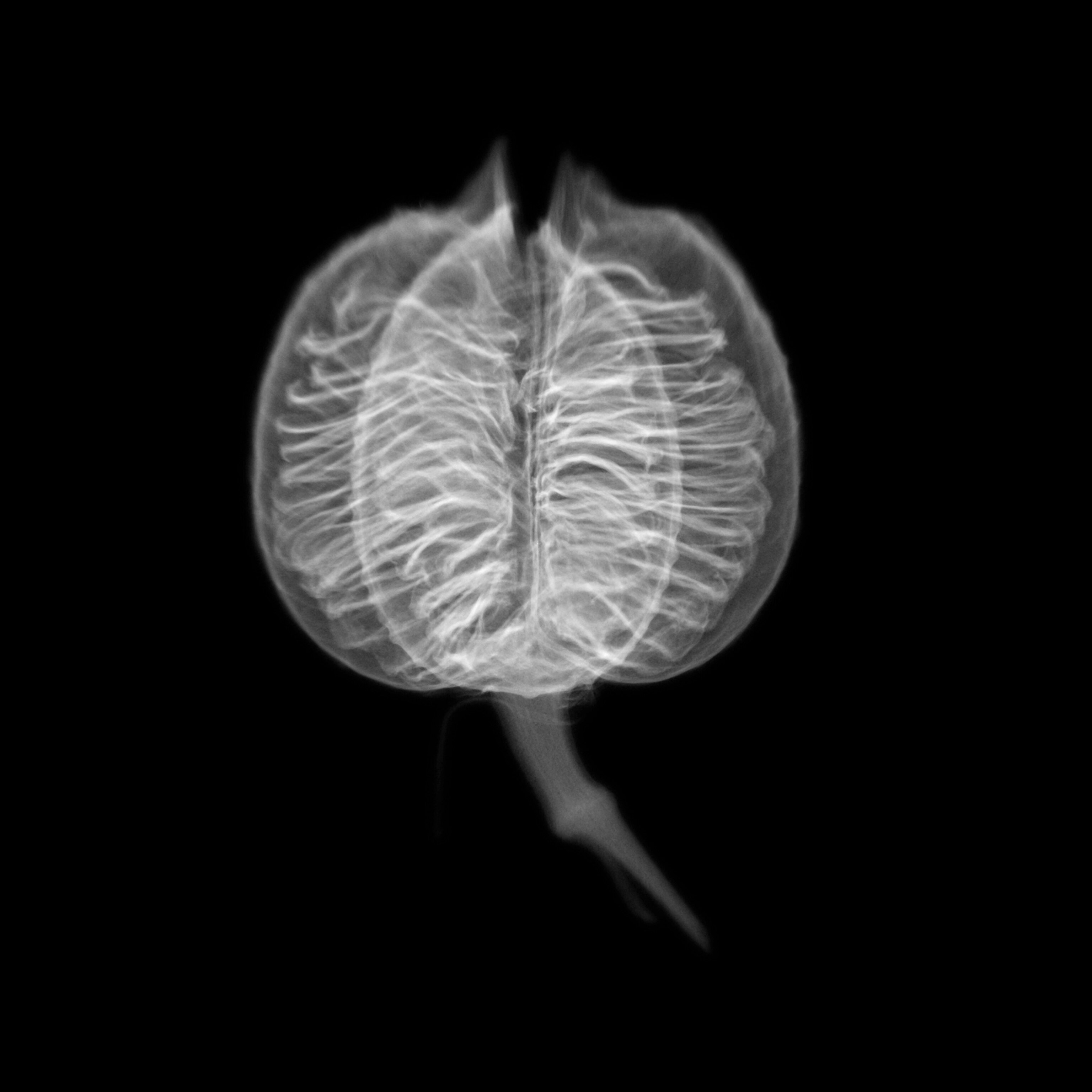

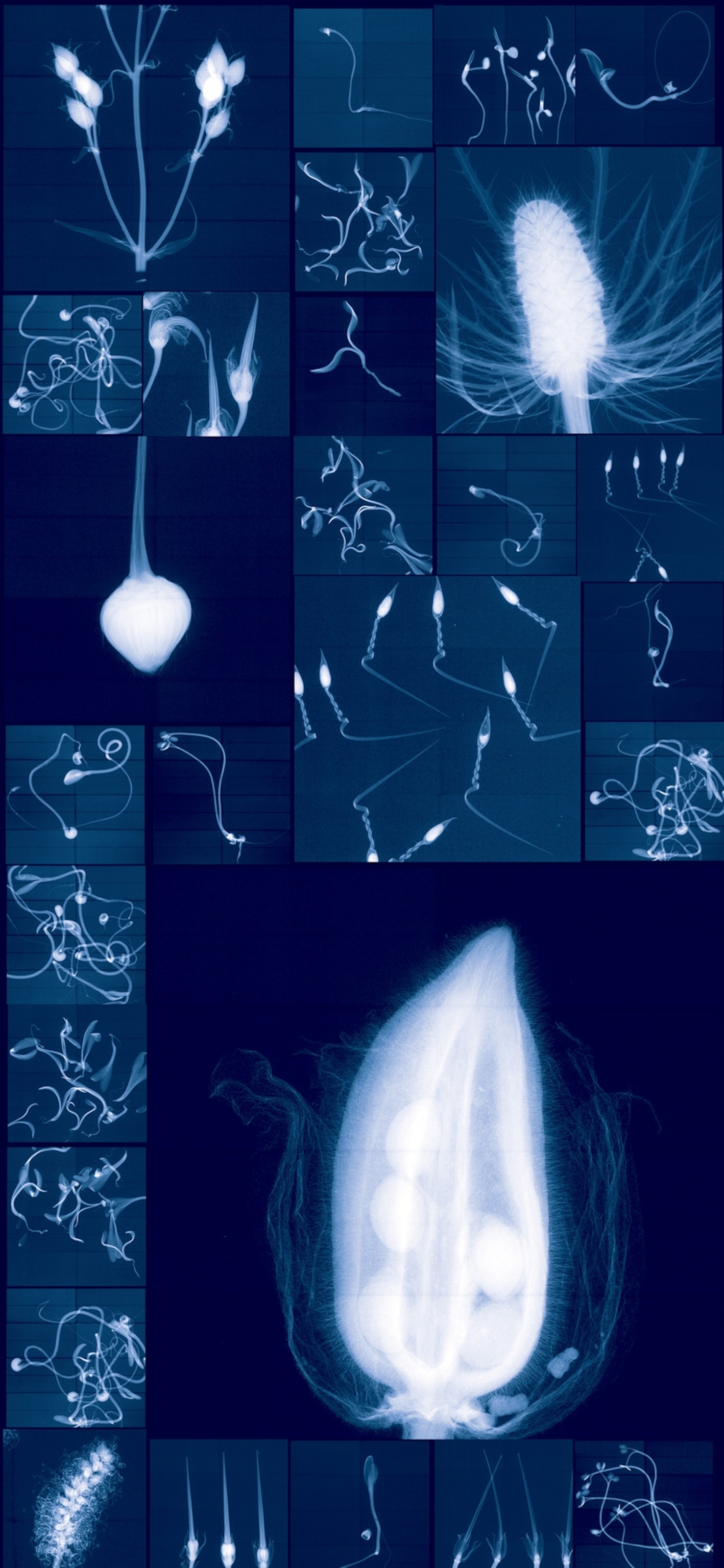

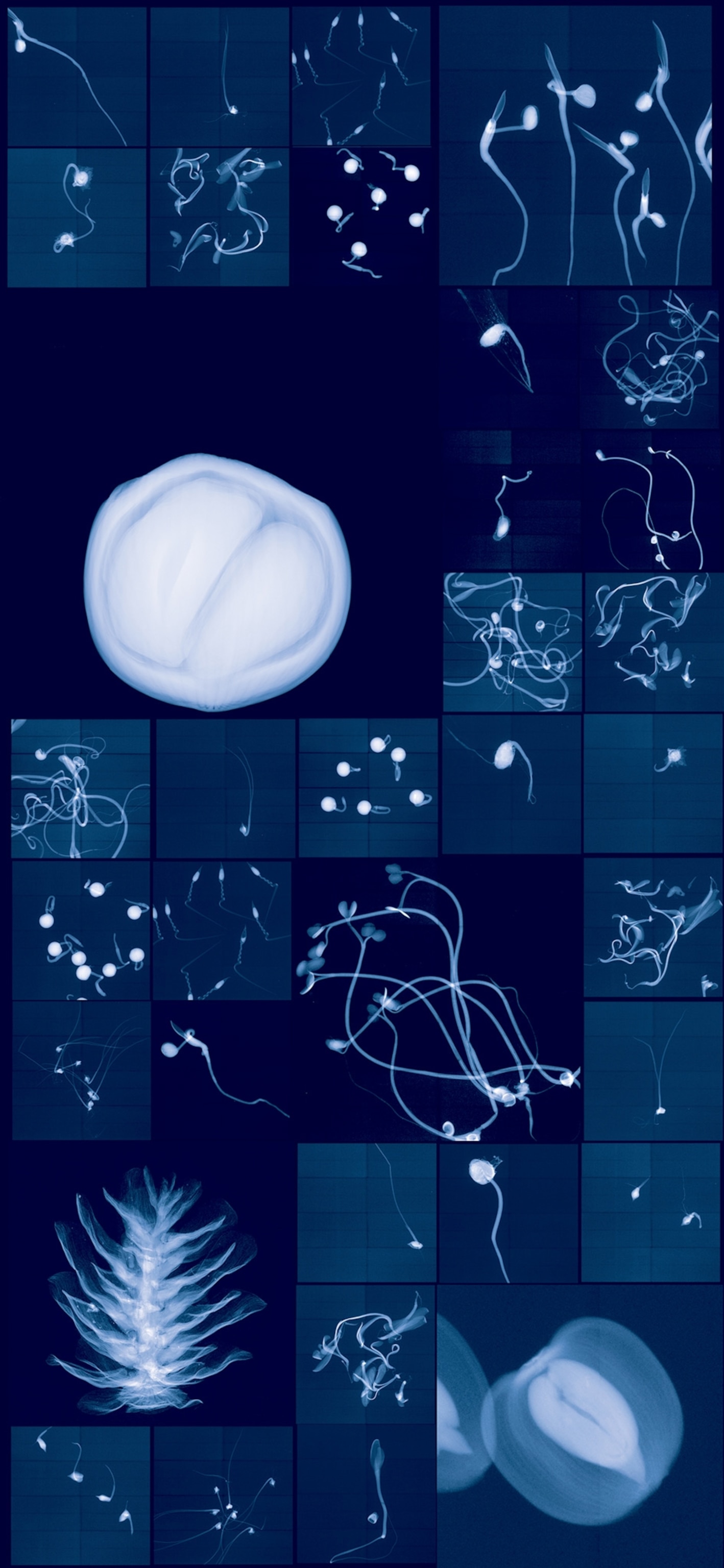

To make her images, Doherty uses x-ray machines. Working with scientists at each vault, she is given specimens that have been set aside for research purposes, not for storage. She places her specimen inside a petri dish and then inside the x-ray machine, which captures a black-and-white digital image. When she is done taking photographs, Doherty saves all the images to a hard drive that she takes back to her studio in Texas. She then begins the time-consuming process of turning the photographs into colorful images, collages, or animations using Photoshop.

The colors Doherty chooses have specific meaning. Some of her animated images shift from green to brown; this represents the drying process, she says. Others shift from green to blue, to illustrate the idea of being frozen.

“Part of that for me,” she says, “is the quest to place living things in a state of suspended animation. It’s about that impossibility of stopping time.”

Doherty’s work is ongoing. As climate change predictions become more worrisome, she hopes this series will inspire conversations about taking action: “Literally almost all the stories are so dark and so discouraging that to find this little kernel of hope within this greater moment that we’re living through I think is really important.” (Read about the young activists who are going on strike to raise climate change awareness.)

She remembers a story she heard while photographing inside the Millennium Seed Bank in England. Someone once discovered a mysterious bag of seeds at home in the attic —probably collected more than a hundred years ago by a seafaring ancestor, Doherty says—and brought the seeds in to the bank. The bank analyzed the seeds, germinated them, and realized they’d grown a plant that was thought to be extinct.

“So almost accidentally, you have this seafaring captain who collects a bag of seeds and it survives,” Doherty says. “Those kinds of stories give me hope.”